By Sam McGowan

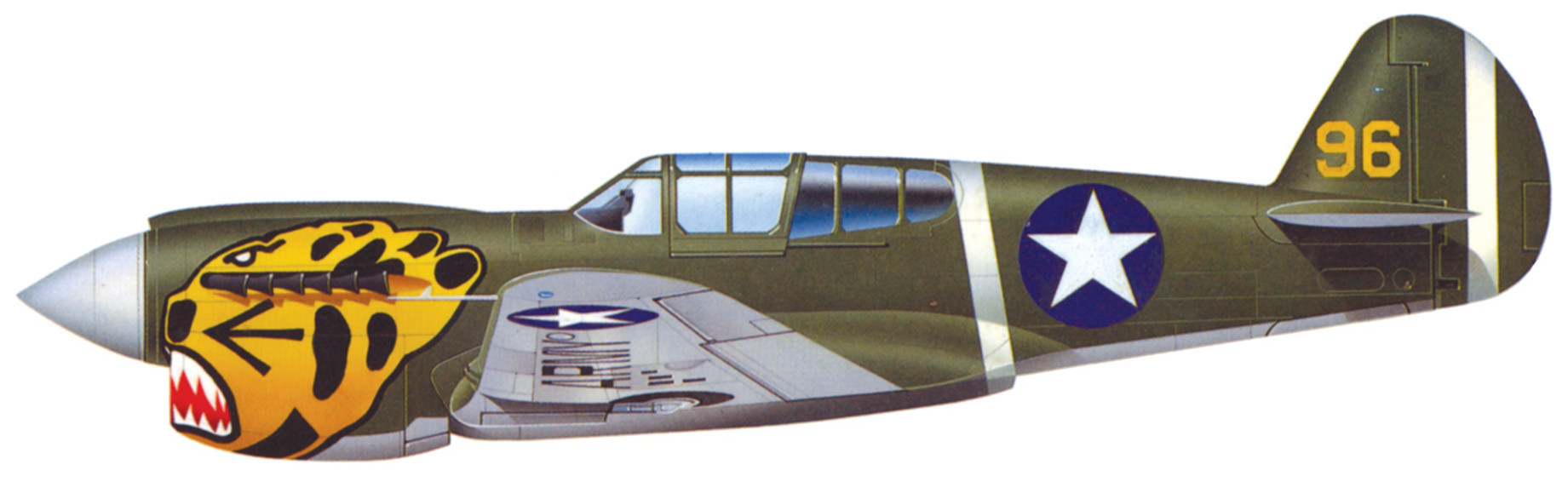

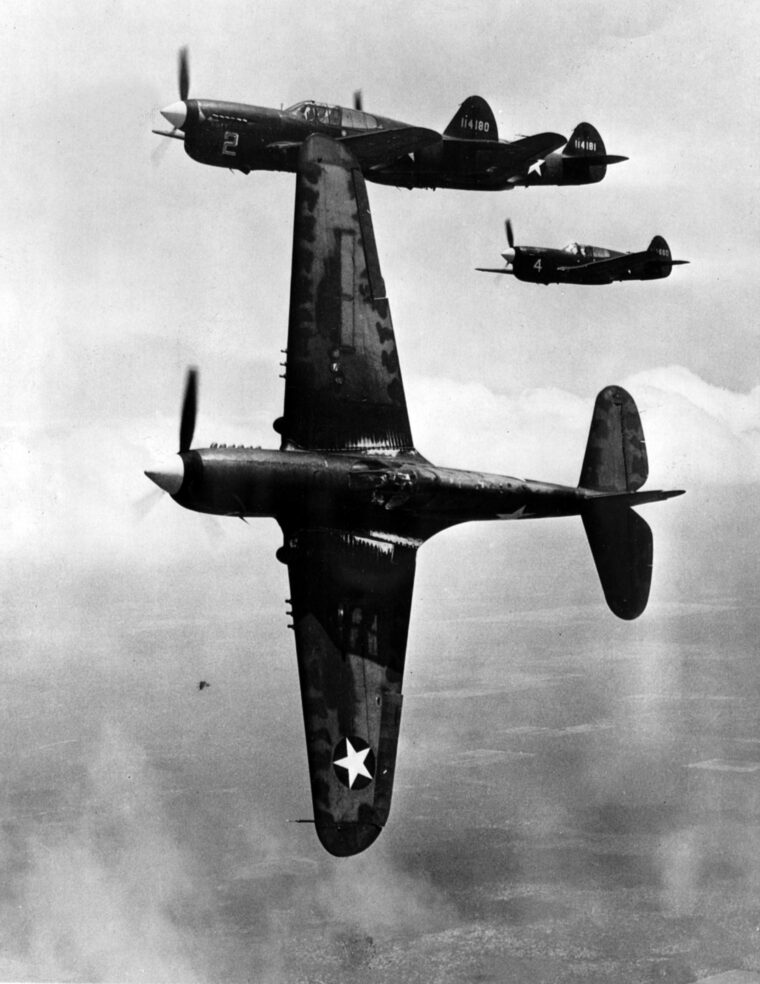

During the first year of American participation in World War II, the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk (Kittyhawk or Tomahawk to the British) came to symbolize the United States Army Air Corps as it fought a desperate war to hold the Japanese in check. This was thanks in large measure to the highly publicized exploits of the American Volunteer Group during the first six months of the war and of their successors in the 23rd Fighter Group in China. Although the P-40 lacked the performance of the twin-engine Lockheed P-38 Lightning and Republic’s radial engine P-47 Thunderbolt, it—along with the Bell P-39 Airacobra—was one of two types of pursuit planes that were available in large numbers at the outbreak of war and the only ones immediately available for service in the Pacific.

Several squadrons of P-40s were sent to the Philippines in the months prior to Pearl Harbor as the United States decided to beef up its military presence there in response to Japanese aggression in Asia, and more were on their way when the Japanese struck. In mid-1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the shipment of enough P-40s to equip four squadrons in China. American and Australian pilots fighting against nearly overwhelming odds in P-39s and P-40s would symbolize Allied determination in the China-Burma-India Theater in the dark, early days of the war.

Curtiss Aircraft Company developed the P-40 as part of its Hawk line of fighters, which began with retractable-gear biplane pursuit ships that served in Army Air Corps squadrons in the 1930s. Its immediate predecessor was the P-36, a monoplane that featured the R-1830 radial engine. To create the Warhawk, Curtiss adapted the Allison V-1710 liquid-cooled in-line engine to the P-36 fuselage. The narrow frontage presented by the Allison significantly reduced drag and greatly improved the original design’s performance.

The P-40, as it was originally designed, was poorly armed, with only two machine guns mounted on top of the nose, but the armament was increased with subsequent versions and most combat models of the P-40 carried six .50-caliber machine guns. Hard points were added under the wings for bombs and rockets, turning the Warhawk into a potent ground attack airplane.

Both the P-40 and the smaller P-39 were products of 1930s U.S. military policy, which called for defending the coasts. Consequently, both designs were intended primarily to support ground troops. Little consideration had been given to interception of enemy aircraft, since the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans provided the best defenses against attack from either Europe or Asia. There were no aircraft in existence in the 1930s with the range to make a transoceanic attack on the United States. Although naval aviation was coming into prominence, neither Germany nor Japan was considered capable of mounting a carrier-borne attack on the United States or even Hawaii.

The threat the Army sought to defend against was an amphibious assault from the sea, and both fighters were designed with that in mind. It was not until war broke out in Europe and the bomber became a preeminent weapon that aerial interception came to be seen as an important Air Corps mission.

The low altitude operations required for ground support placed aircraft in range of everything from small arms to heavy antiaircraft fire, so the P-39 and P-40 were designed to absorb ground fire and keep on flying. These qualities would prove beneficial in the ground attack role, but both airplanes were severely lacking as interceptors due to their lack of high-altitude performance capabilities.

The P-39 was a nimble aircraft that could hold its own with Japanese fighters at lower altitudes, but the heavier P-40 was considerably less maneuverable. But, while they were lacking in climb and high-altitude performance, both types were rugged airplanes and would prompt the admiration of those who flew them into combat in the Pacific. General George C. Kenney would report that both designs could “slug it out, absorb gunfire, and fly home.”

In the spring of 1941, the United States began a buildup of forces in the Philippine Islands as the War Department modified its Rainbow No. 5 war plan. Previous military plans had called for U.S. forces to withdraw to a line from Alaska to Hawaii, but Japanese aggression in Asia dictated modifications. Under the new plan, the Philippines would serve as a strategic base for attacks on Japanese positions threatening the oil fields in the Netherlands East Indies. In the event of an invasion of the islands, the defending U.S. and Filipino forces were to withdraw to the Bataan Peninsula and wait for reinforcements to arrive from the United States.

Modernization of the Air Corps in the Philippines was crucial to defense of the islands, and in May the first P-40Bs arrived in the islands and were assigned to the 20th Pursuit Squadron, replacing older types. The 3rd Pursuit Squadron was also equipped with P-40s, while the 17th Pursuit Squadron continued flying de Seversky P-35s for the time being. The Philippines Air Force received the antiquated Boeing P-26s that had previously served with U.S. Army Air Corps squadrons in the islands.

The three Army Air Corps fighter squadrons, the first in the Philippines, were organized into the 24th Pursuit Group in August 1941. They were joined by two squadrons of the 35th Pursuit Group, the 21st and 34th Pursuit Squadrons, in November. The 35th Group headquarters was still at sea when the Japanese attack came and never reached Manila; the ship carrying the headquarters was diverted to Australia, where the 35th would reform.

The two later squadrons were equipped with more modern P-40Es, but the 34th Squadron’s airplanes were given to the 17th Pursuit; the 34th received the P-35s the 17th Pursuit Squadron had been flying. Additional P-40s were en route to the islands by sea to replace the P-35s. The 20th Pursuit had received P-40Es by the end of November. The Hawaiian Air Force on Oahu also included several P-40 squadrons. The 15th Pursuit Group at Wheeler Field was equipped with P-40s, as was the 18th Pursuit at Hickam Field. Other P-40 squadrons were deployed to Alaska and the Panama Canal Zone.

A stroke of luck put four squadrons of P-40s with experienced and well-trained American pilots in China before war broke out. Captain Claire Chennault had gone to China in 1937 after his retirement from the Army to take a position as a civilian advisor to Generalissimio Chaing Kai-Shek’s Nationalist Chinese government. At the time of his retirement, Chennault was not only one of the most experienced and skilled fighter pilots in the Air Corps, but he was an outstanding tactician who knew how to use the best qualities of the aircraft under his command.

General Walter Short Believed That the Greatest Threat to the Army Fighters was Sabotage

Over the next four years, Chennault experienced Japanese aggression firsthand and became an expert on enemy tactics. Even more important, he conceived tactics to challenge the Japanese. Experiments with mercenary pilots from Europe had proven nearly fruitless. As it was, in 1941 China still lay practically defenseless against Japanese air attack. The Chinese government appealed to the United States for help. T.V. Soong, the brother-in-law of Chiang Kai-shek, lobbied in the United States on behalf of China. His requests included American-built bombers and fighters to augment the Chinese Air Force, as well as American pilots to fly them in combat.

During a visit to the United States, Chennault managed to convince President Roosevelt to authorize what would later be known as a covert military operation, including the recruitment of experienced U.S. Army, Marine, and Navy fighter pilots for duty in China. The young officers were “sheep-dipped,” meaning they were officially discharged from the service to which they were assigned and allowed to contract with Chennault’s American Volunteer Group as civilians. While they had been officially discharged from their respective services, the volunteers were led to believe that they could return to them when their contracts in China were up.

Although the men of the AVG did not consider themselves to be mercenaries, nevertheless, that is what they were. Another part of the deal was the supply of enough P-40s to equip four squadrons. The initial batch of 100 airplanes came from a consignment that was supposed to have gone to Sweden.

The Japanese attack on Hickam Field on December 7, 1941, nearly wiped out the 18th Pursuit Group. General Walter Short, the senior Army officer in Hawaii, believed that the greatest threat to the Army fighters was sabotage, and he ordered that the Army aircraft be parked close together so they could be more easily guarded. No one in Washington or Honolulu considered a carrier-borne aerial attack to be a significant threat.

The Japanese attack caught the U.S. military in Hawaii completely by surprise, and Hickam was hit especially hard. Only two of the group’s P-40s managed to get off the ground, and both were promptly shot down. Wheeler Field fell under Japanese attack, but four P-40s and two P-36s managed to become airborne. Japanese planes failed to strike the small field at Haleiwa, where the 47th Pursuit Squadron was based. Six squadron pilots, Lieutenants Harry M. Brown, Robert J. Rogers, Kenneth A. Taylor, John J. Webster, and George S. Welch drove to the airfield, took off in P-40s and P-36s, and headed out to meet the Japanese. The small group of fighter pilots managed to inflict appreciable damage on the attacking force. Welch alone claimed four Japanese planes shot down.

Although many historians have written over the years that the Air Corps in the Philippines was caught on the ground and wiped out on the first day of the war, this assertion is more myth than reality. In fact, the American and Filipino fighter squadrons had been on alert for weeks, and fighters were in the air over the Philippines long before the first Japanese aircraft appeared overhead. The pilots stood by their airplanes, even sleeping on the wings.

As soon as word of the attack on Pearl Harbor reached Manila, fighters were ordered aloft on combat air patrols. The 3rd Fighter Squadron at Iba went out during the early morning hours in an attempted intercept of a large Japanese formation that had been detected by the Iba radar site. Even though radar showed the P-40s intercepting the formation, they were apparently beneath them and were unable to see the Japanese bombers in the darkness. There is some confusion over the identity of these unidentified aircraft.

Later in the day, the Japanese 11th Air Fleet bombers and fighters that struck Clark Field, and apparently Iba as well, were kept on the ground by fog on Formosa, but Japanese Army bombers were in the air. At least two attacks were made on cities on Northern Luzon, and P-40s from Nichols Field were sent up to intercept them. In the late morning, the Iba radar site picked up another large Japanese formation over the China Sea, and the 3rd Pursuit was launched to defend the base. By the time the Japanese actually reached the Philippines, the P-40s were running low on fuel. One flight was preparing to land at Iba when Japanese fighters came in to strafe the field.

The P-40 pilots pulled up their wheels and turned into the Japanese, breaking up the strafing attack. Unfortunately, bombs dropped by high-level bombers did tremendous damage to the base, including the destruction of the radar site, but the airplanes were all aloft and were not hit by the bombs. None of the P-40s were destroyed in the attack.

One pilot who had been in the landing pattern when the attack came ditched his P-40 in the surf right off the small grass airfield. Several P-40s were forced down when their new engines seized. The airplanes had just arrived in the Philippines, and there had been no time to break the engines in before they were engaged in combat. The inability to slow-time engines on newly assembled P-40s would be a major factor in the defeat of the Army Air Corps in the Philippines.

The Japanese got really lucky at Clark Field . The 20th Pursuit Squadron had been sent north to search for the Japanese bombers that appeared over Northern Luzon in the morning, and when their fuel ran low they diverted to Clark. As the P-40s were refueled, they taxied out in flights to return to the air, but only one flight of four, led by squadron commander Lieutenant Joe Moore, was airborne before the attack came.

The Japanese bomb pattern ran right across the ramp where the P-40s were being serviced, and the remaining 14 fighters were wiped out. Moore and his wingmen took on the Japanese attackers. Lieutenant Randall Keator was the first to score, thus becoming the first American fighter pilot in the Pacific Theater to shoot down a Japanese plane. Moore shot down two fighters, and other P-40 pilots, including a flight from the 3rd Pursuit at Iba that was in the vicinity of Clark, also managed to get in their licks. P-36 pilots also claimed several hits on Japanese aircraft.

The near destruction of the U.S. Army Air Corps in the Philippines on December 8 led to the myth of Japanese aircraft superiority in the early days of the war, a myth that prevails today. The Japanese fighters were very light in weight compared to the American P-40s and were thus more effective at higher altitudes. At lower altitudes, the P-40s were able to hold their own, and if a P-40 pilot managed to hit a Japanese fighter, it would probably go down. The reverse was not true. The rugged P-40s could absorb tremendous amounts of fire and still keep flying.

While the Japanese fighters were extremely agile, they were not invincible. Had the U.S. air units in the Philippines been properly trained and equipped, the Japanese would have had a very difficult time gaining control of the air.

Wagner, the First American Ace of the War, Quickly Grasped the Deficiencies of the Japanese Fighters.

Engine failure accounted for more P-40s lost in the Philippines than enemy fire. Limited fuel capacity was another problem. Many pilots were forced to bail out or crash-land due to fuel exhaustion, particularly on December 10 when the Japanese raided Manila and a huge dogfight ensued.

Quite a few P-40s were also lost in takeoff and landing accidents that were a direct result of inexperience. Most of the young pilots in the Philippines were fresh aviation cadets and had little practical flying experience in the high-performance fighters to which they had been assigned. Several of the experienced fighter pilots achieved spectacular results against the Japanese, usually fighting against vastly superior forces.

There were bright spots in those opening weeks of the war as P-40 pilots performed spectacular feats of heroism. After the huge battle on December 10, the Far East Air Forces fighter force had been so reduced that fighter commander General Harold George decided to hold the P-40s for ground attack missions instead of sending them out on interceptions.

Pilots such as Boyd Wagner, Grant Mahony, and William Dyess were especially aggressive. Mahony carried out a particularly daring attack on a Japanese radio station and airfield at Legaspi. A few days later he was evacuated to Australia, where he was put in charge of training recently arrived pilots. Mahony would eventually go to India and then to China, returning to the Philippines in the final year of the war. Ironically, he died in combat in the Philippines while flying a P-38.

Wagner was a highly skilled pilot and aeronautical engineer who quickly grasped the deficiencies of the Japanese fighters. He became the first American ace of the war and was also evacuated to the Philippines. He took command of a P-39 squadron and moved north to Port Moresby in Papau, New Guinea, in mid-1942. Dyess remained on Bataan and became a POW. He led the last significant American air attack before the surrender of Bataan when he and three other P-40 pilots bombed Japanese ships in Subic Bay.

Dyess fell into Japanese hands when the forces on Bataan surrendered and remained a POW for several months until he managed to escape and make his way to Australia. Other pilots performed particularly heroic acts, including Lieutenant Russell Church, who stayed in his burning P-40 and strafed a row of Japanese fighters parked at the airfield at Vigan, instead of pulling up after his airplane was hit to gain enough altitude to bail out.

It is almost unbelievable, but P-40s continued the fight in the Philippines right up to the final Japanese victory at Mindanao. Several P-40s were flown out of Bataan to Mindanao, while three were safely delivered by ship to Cebu in the southern Philippines. They were reassembled and flown to Mindanao before the Japanese occupied Cebu. One of their last actions was escorting American bombers that had flown up from Darwin, Australia, in April for offensive actions against Japanese installations at Davao and Cebu.

When it became apparent that the Japanese would capture Del Monte Field, as many of the pursuit pilots as possible were evacuated to Australia to join their comrades. They were to serve as a nucleus for the Fifth Air Force fighter squadrons that would gain air superiority in the Southwest Pacific.

On December 20, 1941, President Roosevelt decided to leave the Philippines to its own fate, and the War Department ordered the headquarters of the Far East Air Forces (FEAF) to Australia. Personnel arriving in Australia discovered a force in disarray, with no organization and little military discipline at all. In late December, Captain Paul I. Gunn, a former U.S. Navy enlisted aviator who was living in the Philippines when the war broke out, was ordered to fly a load of FEAF staff members to Australia and to remain there. Gunn, whose family was still in the Philippines, was appalled by what he saw and immediately took it upon himself to get things going. Gunn knew that a contingent of fighter pilots had just arrived in Australia from the Philippines, and he proceeded to organize a fighter squadron. Men and airplanes were organized into a new 17th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional), an appropriate designation since a dozen of the pilots had been in the original 17th Pursuit in the Philippines.

When the 17 fighters had been assembled, Gunn led them north to Darwin in his personal Beechcraft transport. Two P-40s were lost to accidents during the trip north. The pilots—most of whom had come out of the Philippines—thought they were on their way back to help their buddies at Bataan, but when they reached Darwin they learned that they were going to Java instead.

A total of 39 P-40s reached Java, but only six were still flying when the 17th Pursuit was told to turn its remaining airplanes over to the Dutch and prepare for evacuation to Australia. The Dutch never got the P-40s into operation. They were destroyed by a Japanese strafing attack shortly after the Americans left. A large number of P-40s were lost when the ships they were on were sunk before they reached Java.

The one bright spot for the Allies during the early months of the war was the spectacular number of Japanese aircraft shot down by Chennault’s American Volunteer Group in China, which became the stuff of legend and earned the nickname of the Flying Tigers.

Before sending the AVG pilots up against the Japanese, Chennault, who was one of the most skilled fighter pilots in the world, put them through an extensive training program. He taught them tactics that he had developed based on his knowledge of the capabilities and methods used by the Japanese. The AVG went into action on December 20, 1941, intercepting a formation of Japanese bombers on the way to Kunming and breaking up the enemy formation. Three days later, other AVG P-40s inflicted heavy losses on Japanese aircraft attacking Rangoon.

Chennault knew the limitations of the P-40s, and he taught his pilots to take advantage of the airplane’s superior diving and level-flight speeds. The two-ship element was the key to the AVG’s success, and the American pilots operated their Warhawks using hit-and-run tactics, knowing that if they tried to fight the Japanese on the enemy’s terms, they would come out on the losing side.

In some ways, the AVG pilots were fighting a losing battle since the Japanese were gaining the upper hand in Burma and were advancing in China. Since the United States was now officially in the war, the War Department made plans to bring the AVG into the Army Air Corps, with the idea that they would form the a nucleus for an air force in China.

The Sinking of the Carrier Langley with a Load of P-40s Onboard, as well as other Heavy Casualties in Java, Reduced the Far East Air Forces to Less than 100 Fighters

Most of the AVG pilots had other plans, however, and only a handful agreed to remain in China with the U.S. Army. Some preferred to retain their civilian status as pilots for China National Airways, a civilian airline connected to Pan American. Many of the AVG pilots had come from the Navy or Marine Corps, and they wanted to return to their former services, while some of the former Army pilots were just plain mad at the new Tenth Air Force apparatus in India and wanted no part of it. The AVG contracts were due to expire on July 4, 1942, and in the interim the pilots continued to fly and fight as civilian contractors.

War Department plans called for the creation of a full pursuit group in China. The new group was the 23rd Fighter Group (the pursuit designation was changed to fighter in mid-1942), with Colonel Robert L. Scott as the commander. A few former AVG pilots and more mechanics and other support personnel elected to accept induction into the 23rd, and they and their P-40s would serve the main Allied air effort in China. The P-40 would be the principal fighter in the CBI until 1944.

After the defeat in Java, the Far East Air Forces in Australia began building up a force to oppose the Japanese. Although more than 300 P-40s had arrived in Australia by the end of March, heavy losses, particularly when the carrier Langley was sunk with a load of P-40s being ferried to Java aboard, followed by the subsequent abandonment of a shipment carried aboard the freighter Sea Witch, had reduced their numbers to less than 100. The 49th Fighter Group arrived in early February, but its pilots were not considered ready for combat.

With the defeat of the Allies in Java, Japanese air forces in the Netherlands East Indies were within range of Australia’s northern coastal cities. Darwin fell under frequent air attack, and the P-40-equipped 49th Fighter Group was sent there to defend the city while the 8th and 35th Groups, both of which were equipped with Bell P-39s and P-400s, were charged with defending Papua, New Guinea. The P-400 was an export version of the P-39 that had been originally built for the British.

The young fighter pilots in Australia learned the P-40’s limitations and advantages, and like the AVG in China, used the knowledge successfully against the Japanese. Just how effective the P-40s could be was demonstrated on August 23, 1942, when 49th Group pilots shot down 15 Japanese bombers and fighters. Between April and August, the 49th Group shot down more than 60 Japanese planes and gained air superiority in the skies over Darwin. Captain Andrew Reynolds of the 9th Fighter Squadron was the top-scoring Far East Air Forces ace at the time, with 10 enemy airplanes to his credit. With Darwin out of danger, the 49th Fighter Group moved north to New Guinea. By the end of the year the group had begun replacing its P-40s with twin-engine Lockheed P-38s.

Due in part to a shortage of American pilots, several Royal Australian Air Force fighter squadrons were given P-40s, which they dubbed Kittyhawks. The Aussie fighter pilots were courageous and inspired by their role of defending their homeland from Japanese aggression. The P-40 was vastly superior to their locally produced Commonwealth Wirraway.

Although British Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires would eventually be sent to Australia, the P-40 would become the primary RAAF fighter. Australian P-40s played a significant role in the Battle of Milne Bay, a decisive battle that forced the Japanese to abandon plans to capture Port Moreseby. A squadron of RAAF P-40s operated out of the airfield at Milne Bay, attacking the Japanese landing party with bombs and machine-gun fire. Australian squadrons continued flying P-40s until late in the war.

Like other prewar designs, the Warhawk was produced for export. The British designated theirs as Tomahawks or Kittyhawks, depending on which version they were. RAF Kittyhawks and Tomahawks served primarily with the Desert Air Force in North Africa. Since the RAF’s Hurricanes and Spitfires were better suited for interceptor duty, their P-40s were used primarily in support of ground forces. During the late summer of 1942, U.S. Army Air Forces P-40s arrived in the Mediterranean with the 57th Fighter Group, which began training with the RAF in Palestine. The group entered combat in North Africa with the Ninth Air Force and fought in the battle of El Alamein. The 79th and 324th Fighter Groups also flew P-40s with the Ninth Air Force.

The 33rd Fighter Group was selected for duty in North Africa with Twelfth Air Force in September 1942, less than 60 days before the planned date for Operation Torch, the invasion of French North Africa. To expedite their arrival, the group’s P-40s were loaded aboard the escort carrier USS Chenango. As Lt. Col. William W. Momyer led his group off the carrier on November 10, word reached the vessel that the airfield at Port Lyautey was secure.

Although the launchings themselves went off with few problems, the deliveries were a disaster. One P-40 crashed into the sea, another flew off into a fog bank and disappeared, and 17 were damaged in landing accidents. Even though nearly a year had passed since the disaster in the Philippines, inexperienced American fighter pilots still found the P-40 difficult to land. None of the 33rd Group’s P-40s got into action during the invasion. The landing problems put a halt to the launchings, and the remainder of the 77 Warhawks did not leave the carrier until two days later.

Palm Sunday Massacre

An additional 35 airplanes arrived off Morroco on the British carrier Archer to reinforce the 33rd Group. Four of those airplanes were also lost when their inexperienced pilots cracked them up on landing. The 33rd saw intense action in the North African Campaign and suffered so many losses that by February 1943 the group had so few airplanes and pilots that it had to be relieved. The 325th Fighter Group, which was supposed to go to Ninth Air Force in the Middle East, was diverted to Twelfth Air Force and arrived in North Africa in February.

One of the most spectacular events of the North African Campaign occurred on April 18, 1943, when four squadrons of P-40s from the 57th and 324th Fighter Groups escorted by Spitfires intercepted a large formation of German transports as they were returning from an aerial resupply mission for the Afrika Korps in Tunisia. Although the transports were hugging the sea, the P-40s spotted them and went in for the kill. The battle became famous as the Palm Sunday Massacre. The P-40s put in claims for 100 tri-motored Junkers Ju-52 transport planes as well as 16 of their escorts. Allied losses amounted to six P-40s and a single Spitfire from the top cover.

The action continued the following day when 12 more transports were shot down. The successful interception effectively ended German efforts to resupply and reinforce the Afrika Korps in North Africa and hastened its eventual surrender to the superior Allied forces.

After the successful defense of Darwin, Fifth Air Force P-40s moved north to New Guinea and assumed the ground attack role, supplementing the converted Douglas A-20 Havoc gunships and P-39s which had borne the brunt of the low-altitude attack role in New Guinea in mid-1942. Similarly, attacks on ground targets were a major mission for the P-40s of the China Air Task Force, the forward element of the Tenth Air Force commanded by Chennault in China. The CATF became the Fourteenth Air Force in the spring of 1943.

In the spring of 1944, the Allies went on the offensive in the CBI as British Brigadier Orde Wingate’s Chindit force prepared to penetrate Japanese defenses in Burma. Almost simultaneously, the Japanese launched an offensive into India’s Arakam Valley, in which many of the Allied air bases were located. The emergency created by the Japanese offensive led to the movement of several American air units from the Mediterranean to India, including the 33rd and 81st Fighter Groups. The 33rd was already equipped with P-40s, and the 81st equipped with them when it arrived in the CBI. Both groups eventually moved to China and joined Fourteenth Air Force.

By 1944, more capable fighters, such as the P-38 Lightning, P-47 Thunderbolt, and the North American P-51 Mustang, were becoming available. As they did, they replaced the older P-39s and P-40s in the veteran American squadrons. As the American squadrons converted, their P-40s often went to Allied squadrons serving in the same theaters. Several squadrons of the Royal Australian and Royal New Zealand Air Forces equipped with P-40s as the American squadrons were converting to P-38s in the Southwest Pacific.

By 1945, the role of the P-40 had diminished, but veterans of the Pacific War knew that without them, it was unlikely that the Allies would have been able to hold back the Japanese during the dark early days of the war.

Sam McGowan is the author of The Cave, a novel of the Vietnam War. He has also written extensively on the subjects of aircraft and air transport during World War II.

I enjoyed your article very much. I knew a WW2 SEABEE that was sationed at PORTMORSBE, who told of off loading fighter planes and putting them together,then having to deliver them to the airfields. On the way they would have to cut trees down,so the wings of the planes would not be damaged.