By Mike Phifer

Despite the incessant German shelling that had been hammering away at the French lines to their immediate left near the rubble-strewn city of Ypres in northwestern Belgium, the largely untested soldiers of the Canadian 1st Division found the early spring day of April 22, 1915, surprisingly warm and pleasant. Worn out from a long night of stringing barbed wire and repairing trenches in the infamous Ypres Salient of the Allied front, the men lounged at ease in their forward positions. Behind the lines, reserve troops played casual games of soccer, while their officers enjoyed a gentlemanly round of polo. Even when the shelling shifted to the Canadian position in the late afternoon, the troops were not unduly alarmed. Eventually, the bombardment petered out and German planes that had been circling over the front lines abruptly disappeared.

Suddenly, around 5 pm, heavy rifle fire and renewed shelling broke out in the French sector of the salient. Then an ominous yellow-green cloud began to drift toward the French lines, pushed along by a warm westerly breeze. What had been a beautiful day was about to turn very ugly indeed.

The Canadians comprising the 1st Division were all starry-eyed volunteers, eager young men who had flocked to recruiting offices across the nation after word reached the various provinces on August 4, 1914, that Great Britain was at war with Germany. Although a self-governing dominion that looked after its own domestic affairs, Canada was still part of the British empire and when Great Britain was at war, Canada was at war. Plans were quickly made to raise a division of 25,000 men to rush to Britain’s aid. By September 8, almost 33,000 men had joined up to fight. Another 2,000 would arrive shortly at Quebec’s newly constructed Camp Valcartier.

Within a month, the volunteers were organized into three infantry brigades—12 battalions in all—and other troops went into cavalry, artillery, engineering, signal, and medical units. On October 3, some 31,000 Canadian troops filed onto 30 transport ships for passage to England. Eleven days later the convoy, accompanied by a Royal Navy battleship and cruiser, docked at Plymouth to a warm welcome from cheering crowds. Awaiting the 1st Division was their new commander, Lt. Gen. Edwin Alderson, a veteran of 36 years in the military. A kindly, gentle man, Alderson had commanded Canadian troops in the Boer War. He would prove popular with the men in his new command as well.

Entering the Flanders Front

The newly arrived Canadians were sent to Salisbury Plains, 100 miles northeast of Plymouth, where they began four months of intensive training near the famous Druid shrine at Stonehenge. It rained for 89 of the next 123 days, and many of the recruits came down with the flu, sore throats, and meningitis. Twenty eight men would eventually die of the latter disease. Finally, in February 1915, the much-awaited order came for the 1st Division to sail to France. Before they left, Alderson replaced the men’s uncomfortable boots and scratchy tunics with better quality British goods. Much to their chagrin, however, the men retained the widely despised .303-caliber Ross Rifle, which had an unfortunate tendency to jam when fired rapidly or loaded with British ammunition.

Once in France, the 1st Division was sent to a quiet sector of the Flanders front and paired with a veteran British unit for advanced training. Officers and men rotated into the front-line British trenches for 48 hours at a time to gain a little first-hand experience. The division then moved on to Fleurbaix, where it enjoyed a front-row seat at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle on March 10-13. There, the British 1st Army under General Douglas Haig nearly achieved a startling breakthrough of the German lines, only to falter from faulty communications and lack of support. The Canadians’ sole contribution to the fighting was to provide some diversionary fire while British and Indian troops unavailingly attacked the enemy trenches.

Despite their comparative uninvolvement at Neuve Chapelle, the Canadians found their first taste of trench warfare a good learning experience. They were praised by their superiors for being “magnificent men … very quick to pick up new conditions and to learn the tricks of the trade.” It was good that the Canadians were quick learners, for they were soon transferred to General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien’s 2nd Army, stationed in the center of the 17-mile-deep Ypres Salient held by Allied troops in northwest Belgium. In mid-April the Canadians moved into line to take over from the French 11th Division. The position they were entrusted with holding was 4,250 yards wide. The 2nd Brigade held the right half of the sector, the 3rd Brigade the left, and the 1st Brigade was held in reserve.

The Dreaded Ypres Salient

To their dismay, the Canadians found the French trenches an absolute mess. Not only were they widely scattered and unconnected, but they had little in the way of barbed-wire defenses, and the existing parapets were not thick enough to stop an enemy bullet. The newly arrived defenders did not see how the sector could possibly be held if a determined effort was made to take it by a strong force. The trenches also stank since the French had been using them as latrines. Adding to the overall foulness were hundreds of dead German bodies lying between the lines in no-man’s-land. More rotting corpses were discovered when the Canadians began improving their own positions. In one part of their trench the men in the 10th Battalion found a human hand sticking out of the mud. The men took to shaking it wryly as they passed.

By the spring of 1915, the Ypres Salient was considered one of the most dangerous places on the Western Front. It had already seen more than its share of fighting and death. In October and November 1914, a thin line of British regulars repeatedly beat back massive German assaults. By the time the fighting stopped for the winter, almost a quarter of a million men had been killed or wounded. Tactically speaking, the Ypres Salient held no particular military significance for the Allies. The ground, located on the Flanders flood plain, was low and flat, broken here and there by a handful of long, shallow ridges. What terrain advantage there was around Ypres was held by the Germans, who manned the higher ridges overlooking the salient. With excellent observation posts and clear lines of sight, German artillerists were able to rain down torrents of accurately placed shells on the exposed Allied position. The real reason for holding the salient was symbolic, as it was the last remaining piece of contested Belgian real estate still lying in Allied hands. As such it represented their unyielding determination to win the war.

Although the Germans had been stopped in 1914 from taking the salient, they had by no means given up on closing the bulge. General Erich von Falkenhayn, chief of the German General Staff, planned another limited offensive against Ypres in April 1915. Falkenhayn believed the coming attack would act as a diversion from the Germans’ main push against the Russians on the eastern front. It would also give them a better strategic position along the English Channel. Last but not least, it would provide them with a golden opportunity to try out a new and terrible offensive weapon: lung-destroying chlorine gas.

The Debut of Chlorine Gas

The Germans had already experimented with less deadly forms of gas warfare at the first battle of Neuve Chapelle in October 1914, and at Bolymov on the Eastern Front in January 1915. Those attempts, sneezing powder at Neuve Chapelle and tear gas at Bolymov, had been ludicrous failures. In both cases, the chemical agents had failed to disperse, and the Allied troops had not even noticed they were under attack. Later that winter, Nobel Prize-winning German chemist Fritz Haber, then serving in the army reserve, suggested that the German high command consider using chlorine gas, which Haber said could be delivered through a relatively simple system of compressed-air cylinders discharged through exhaust pipes dug into the ground. Such a delivery system, besides being more efficient than gas pellets packed into traditional artillery shells, had the added advantage of not expressly violating the Hague Convention prohibiting the use of gas-loaded projectiles.

With typical Teutonic industry, the Germans began installing Haber’s chlorine-gas cylinders in their trenches along the south side of the Ypres Salient in early March. The cylinders, each five feet tall and weighing 190 pounds, were grouped in banks of 10. They were joined through a manifold to a single discharge pipe controlled by a chemically trained pioneer. By March 10, some 6,000 cylinders were in place. Interestingly enough, the first casualties were three German soldiers who were killed when Allied shells struck some of the cylinders, releasing the gas behind German lines. After two frustrating weeks of waiting for the weather to cooperate and the wind to blow in the right direction, Duke Albrecht of Wurttemberg, commander of the German 4th Army at Ypres, changed the battle plan.

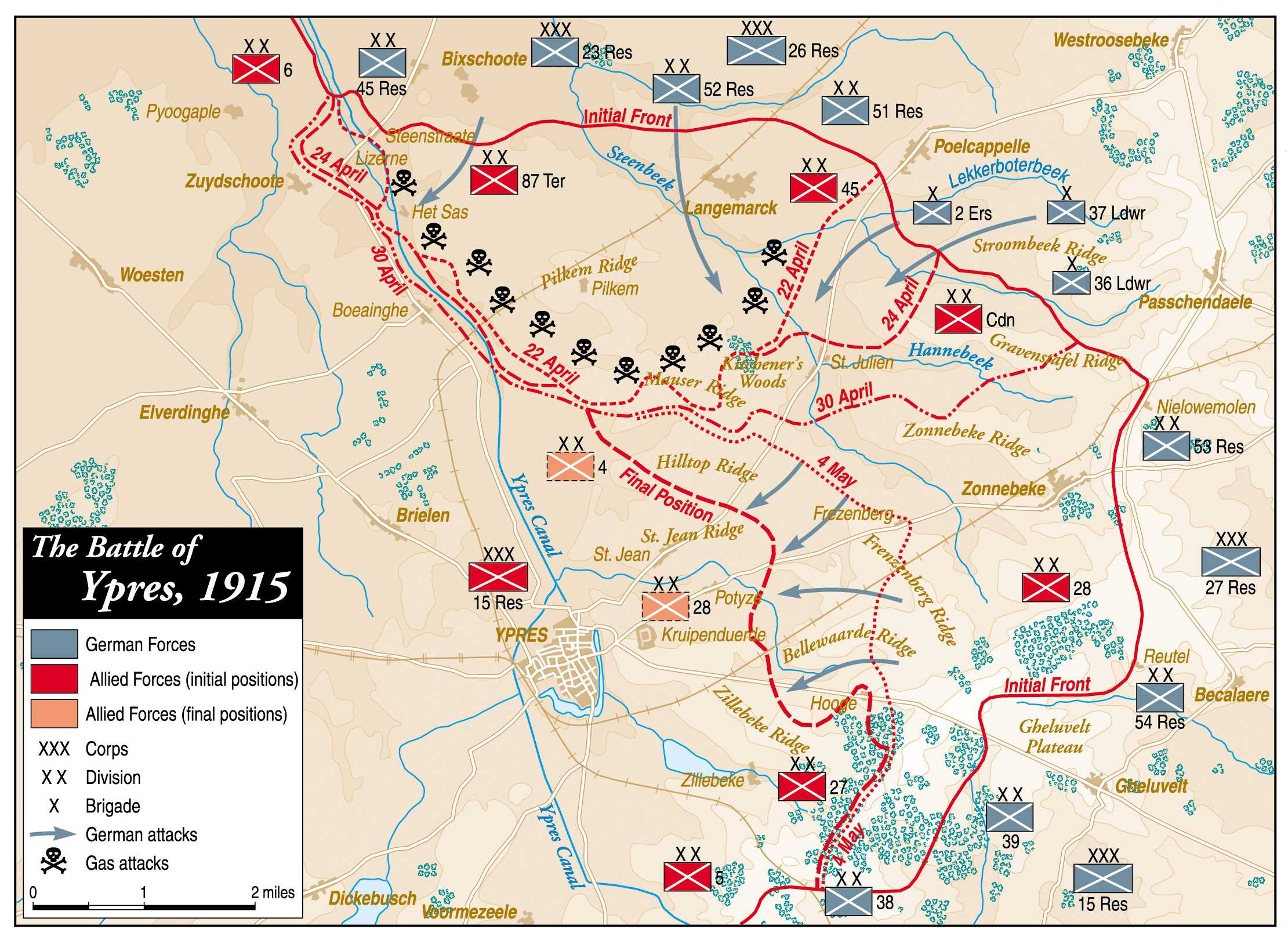

Instead of unleashing the gas against the south side of the salient, the Germans would attack the northern side between the towns of Steenstraat and Poelcappelle. Accordingly, the front-line troops began installing gas cylinders in the trenches facing the northern sector. By April 11, some 5,730 transplanted cylinders were in place. The attack was scheduled for April 15. Two corps, the XXIII and XXVI Reserves, would carry out the assault. Behind a cloud of chlorine gas, they were to drive a mile and a half into the salient and capture the ridge beyond. There, they were to dig in and provide covering fire for additional troops. The Germans believed that the loss of the ridge would make it impossible for the Allies to remain within the salient. Once again, the appointed day brought no westerly wind, and the attack was rescheduled for the 22nd.

Use of ‘Asphyxiating Gas’ Was Imminent

Reports that the Germans were up to something ominous had been filtering into Allied lines for quite some time. On April 13, a German deserter crossed no-man’s-land into the French trenches, bringing with him potentially key information. Interrogated at the French 11th Division headquarters, the deserter talked freely of German troop strength and warned that an attack involving “asphyxiating gas” was imminent. The French division commander took the matter seriously enough to send a warning to the British. The French high command, however, thought they knew better than the officers at the front. They dismissed the threat out of hand and reprimanded the officer in question for communicating directly with the British troops.

Another German deserter denied resolutely that his army was planning to use poison gas. He said the suspicious packet of cotton he was carrying on his person was intended to protect him against a possible French gas attack. On April 16, a Belgian spy confirmed that tubes of asphyxiating gas were indeed being placed along the German front. Belgian intelligence also reported that the Germans had ordered 20,000 mouth respirators from their supply depot at Ghent. British aerial reconnaissance, however, reported that there had been no unusual German movement behind their lines. To be on the safe side, Lt. Gen. Sir Herbert Plumer, commander of the British V Corps, alerted his divisional commanders of a possible gas attack. When the rumored attack did not immediately materialize, life in the trenches returned to normal—but not for long.

On the morning of April 22, German soldiers anxiously waited in their trenches for the final signal to go forward. The attack was scheduled to begin at 5 am, but once again the wind was not cooperating. There was nothing the Germans could do but sit and wait. An entire morning and afternoon passed. Finally, orders reached the front for the men to get ready to go over the top. The attack was on.

A Toxic Cloud of Death and Misery

At 5 pm, the cylinders were opened, spewing some 149,000 kilograms of greenish-yellow chlorine gas through their exhaust pipes toward the French line, which was held by two divisions, the 87th Territorial and 45th Algerian. As roiling clouds of the deadly gas reached the French lines, horrified soldiers began grabbing at their throats, rolling on the ground, and coughing up great gouts of blood as they fought in vain for oxygen. The panicked Territorials scrambled out of their trenches in a desperate effort to escape the toxic cloud. To add to their misery, German artillery opened up on the French lines shortly after the gas was released. Twenty minutes later, German troops wearing cotton masks wrapped with gauze cautiously crept forward into the salient.

Pockets of disoriented French infantrymen attempted to put up some resistance, but most of their comrades had already fled in terror. On the other hand, French artillerymen stuck valiantly by their 77mm guns and began blasting away at the oncoming Germans. By 7 pm, the attackers had silenced most of the guns, capturing 57 of them. The rest were pulled away by the retreating French.

Situated to the immediate right of the French position, the Canadians in the 1st Division watched with growing alarm as their allies ran for their lives. Wildly bouncing ambulances and ammunition wagons crammed with wide-eyed, terror-stricken African troops smashed through hedges and careened over ditches past the Canadians, desperate to escape the horror behind them. Alongside the wagons came more French infantrymen, running weaponless toward the rear. Adding to the intense confusion, Belgian civilians from Ypres also clogged the roads, attempting to escape. The northern part of the salient was quickly becoming a shambles. A four-mile-wide gap had opened in the French lines, and the 50,000 remaining British and Canadian troops were in imminent danger of being cut off.

Urinating on Handkerchiefs as a Last-Ditch Antidote

Slowly but steadily, the hideous yellow-green cloud began drifting toward the Canadian lines. A quick-thinking medical officer, Captain F.A.C. Scrimger of the 14th Battalion, 3rd Brigade, immediately determined that the gas was chlorine and came up with a temporary, and somewhat unusual, solution. Scrimger had the men in his unit urinate onto their handkerchiefs, then tie them around their mouths. In this way, it was hoped that the chlorine would crystallize before they breathed it in. Luckily for the Canadians, the gas already had begun to dissipate, and the men received only a mild gassing, causing watery eyes, runny noses, and slight breathing difficulties.

With the worst danger from the gas averted, the Canadians faced the more pressing task of how to slow down the German advance and plug the gap in the salient. The current situation looked grim. The 13th Battalion, the Royal Highlanders, held the trenches on the left flank as far as the Poelcappelle road, but their own flank had been left unprotected by the fleeing French troops.With the help of a few Algerian troops remaining in the vicinity, Majors Rykert McCuaig and Edward Norsworthy organized a defense along the Poelcappelle-St. Julian road. From a shallow ditch alongside the road, the Highlanders made a brave but doomed attempt to stop the Germans from outflanking the Canadian position. All the troopers were either killed or captured in the brief, sharp fight, but the stand by the 13th Battalion had managed to slow down the Germans and make them wary in the growing darkness.

With the fall of McCuaig’s and Norsworthy’s little force, four guns of the 10th Battery under Major William King were the only remaining resistance along a mile-wide gap between the front lines and Saint-Julien. The guns pounded away at a nearby house the Germans had just captured, then wheeled around to open fire at point-blank range on a column of Germans marching west along the Poelcappelle road. As darkness fell King knew he was in trouble as there was no way he could hold his position for much longer. Just in time, 60 Canadians from the 13th Battalion arrived from Saint-Julien and fell in alongside King’s gunners.

A 19-Year-Old Lance Corporal Holds His Ground

Time after time the Germans attacked, only to be driven back by 19-year-old Lance Corporal Frederick Fisher and his four-man Colt machine-gun crew. After Fisher’s men were killed in the raging fight, he fought on alone, taking his gun to a more exposed position and continuing to mow down the Germans. Meanwhile, King’s gunners dragged off their own guns to prevent them from being captured by the quickly closing enemy. Fisher died defending the battery, and later become the first Canadian soldier in the war to receive the Victoria Cross.

After the fighting withdrawal at Poelcappelle, there was no more organized Allied resistance between Saint-Julien and the Canadian lines. The Germans, however, had been badly bloodied themselves, and they uncharacteristically hesitated, unsure what level of resistance awaited them in the dark. While the Germans halted for the night, the Canadians attempted to plug the mile-wide hole in their line and prevent the enemy from wheeling south and cutting them off inside the salient.

As darkness gathered, the 10th and 16th Battalions were ordered to make a counterattack against the Germans at Kitchener’s Woods, a thick clump of trees immediately west of Saint-Julien. Control of the woods would allow the Germans to penetrate Canadian lines the next morning and capture the town. At 11:45 pm, 1,500 men in the two battalions set out for their jumping-off point, Mouse Trap Farm, 500 yards away. A planned conjunction with French troops never materialized since by now most of the French were far away, but the Canadians moved on as quietly as possible. Two hundred yards from the woods, the men ran into a six-foot-high hedge interlaced with barbed wire. As the Canadians struggled to extricate themselves from the unexpected barrier, a German flare wavered overhead and lit the darkness.

“Come On, Boys, Remember That You’re Canadians!”

The Germans immediately opened up with machine-gun and rifle fire. The Canadians hit the ground to avoid the deadly hail of lead. Major James Lightfoot of the 10th Battalion jumped to his feet and shouted, “Come on, boys, remember that you’re Canadians!” The troops lunged to their feet with a wild yell and charged the woods. Despite intense machine-gun fire, a few determined soldiers reached the German position and drove off the enemy in a wild clash of bayonets.

With the capture of the trench, the remaining men in the 10th and 16th Battalions moved in and cleared out most of Kitchener’s Woods, opening their own 1,000-yard wedge in the German lines. Taking fire from every direction, it soon became painfully clear to the Canadians that they would not be able to hold the woods. Comrades from the 2nd and 3rd Battalions moved up to support the troops, but as daylight dawned they were shot to pieces as they attempted to cross the open countryside. The soldiers already inside the woods hunkered down and held on—for how much longer no one could say.

Across the lines, the Germans were anticipating victory. The XXIII Reserve Corps was given the assignment of crossing the Canal de l’Yser, six miles to the west, and taking Poperinghe. Meanwhile, the XXVI Reserve Corps was to continue driving south against the Canadians. By fording the canal and cutting off the top of the salient, the Germans would force the remaining British and Canadians to retreat. With a five-to-two advantage in men and a five-to-one advantage in artillery, the Germans had good reason to feel confident. Added to this was the fact that the frontage the Canadians now held had almost tripled after the first-day rout of the French territorials.

It Did Not Seem Possible That Any Human Being Could Live in the Rain of Shot and Shell That Began to Play Upon Us

The Canadians worked feverishly to fill the gaps opened by the previous day’s fighting. The most glaring was a two-mile-wide gap west of Saint-Julien. Orders came down from General Alderson himself for the 1st and 4th Battalions of the 1st Brigade to launch a counterattack to relieve the gap. “At 5 o’clock two French battalions are to make counterattack against Pilckem with their right resting on Pilckem-Ypres road,” Alderson wrote. “You will cooperate with this attack by attacking at the same time with your left on this road.”

Throughout the early morning hours the Canadians waited for the French, but once again they failed to show. Lt. Col. Arthur Birchell, who was to lead the charge, thought he saw the French forming at a farm a mile away and gave the order for his own troops to move out. He was wrong. As had happened previously at Kitchener’s Woods, the French did not appear, and the Canadians were forced to make the attack alone. Sixteen hundred men moved in parade order toward the ominously named Mauser Ridge, where the Germans were busy digging in.

The ridge was 1,500 yards away, and the Germans let the Canadians move into easy rifle range before they opened up. Said Corporal Edward Wackett of the ensuing slaughter, “It did not seem possible that any human being could live in the rain of shot and shell that began to play upon us as we advanced. … For a time every other man seemed to fall.” The suicidal attack quickly failed and the survivors took cover behind small piles of manure. Over on the right flank, two companies from the British 3rd Middlesex Regiment joined in the attack and managed to struggle to within 400 yards of the German position before they, too, were stopped. Although pinned down, Birchell would not give up. He asked for and received reinforcements from the 1st Battalion, who arrived to help the 3rd Middlesex seize a farmhouse on the right flank. For the rest of the day, the Allied troops dug in as best they could and struggled to hang on to their hard-won positions.

The British Attempt to Take the Ridge

In the afternoon, the British 13th Brigade arrived on the scene with orders to take the ridge in yet another supposedly coordinated attack with the French. One British force was to attack on the west side of the Ypres-Pilckem road that ran up Mauser Ridge, while another detachment consisting of a battalion each from the Buffs, the Middlesex, the 5th King’s Own, and the 1st York and Lancaster Regiments was to advance through the pinned-down Canadians on the east side of the road. The British charged at 4:25 pm and were instantly shot to pieces, just as the Canadians had been earlier that day. French Zouaves, at last arriving on the scene, advanced slowly in front of the 13th Regiment and promptly dug in, causing the British troops to veer to the right and overcrowd each other, making them prime targets for the rattling German machine guns. The Canadians jumped up to join the attack, but it did little good. The Canadians suffered 850 dead or wounded in the futile attempt to take the ridge, while the British losses were even more staggering, nearly 4,000 in all.

Luckily for the Allies, Duke Albrecht failed to exploit the gaps in their lines, largely due to the vicious British and Canadian counterattacks. That night the Germans moved in an additional 34 battalions to overrun the eight Canadian battalions strung out between Gravenstafel and Kitchener’s Woods. The attack was slated to get under way at first light. To help the advance, the Germans planned to unleash more chlorine gas on the Canadians, fully expecting them to turn tail and run the way the French had done two days earlier.

During the long night of waiting, the Canadians strengthened their tenuous position, bringing in supplies and setting up barrels of water throughout the trenches so that the men could wet their handkerchiefs in case of another gas attack. It was not long in coming. At 4 am, the Germans released a heavy green gas cloud that a northeasterly breeze carried swiftly into the Canadian lines. The 8th and 15th Battalions, which held the 1,200-yard-wide front, received the worst of the gassing.The soldiers of the 8th Battalion, nicknamed the “Little Black Devils,” put their wet handkerchiefs to their mouths as the 15-foot-high wall of gas seeped toward them. The men soon found breathing difficult, and many fell to the ground coughing, spitting, and retching from the fumes. Despite this, the 8th did not run. Instead, they grimly prepared to meet the Germans.

“Imagine Hell In Its Worst Form and You May Have a Slight Idea of What It Was Like”

In order to catch a glimpse of their shadowy attackers, the Canadians were forced to climb out of their trenches to see over the gas. It was a swirling, confused situation made worse by the fact that the hated Ross rifles constantly jammed. Somehow, the 8th Battalion, with the help of enfilading fire from the 5th Battalion, managed to stop the Germans cold. Unfortunately, the 15th Battalion on the left did not fare as well. “Imagine hell in its worst form and you may have a slight idea what it was like,” Sergeant William Miller later commented. Here the gas was so bad that even the wet handkerchiefs did not dampen the effect. To further complicate matters, the 48th Highlanders holding down the apex of the line could not be supported by enfilading fire.

The 15th Battalion broke. With covering fire from two Colt machine guns, the battalion began falling back in the direction of Saint-Julien. Some fell into the reserve trenches on Gravenstafel Ridge. The Germans were on the brink of pouring completely through the weakened Canadian lines. Already, they were within 300 yards of the ridge. If they took the high ground there, the entire Canadian front would be lost.

To protect Gravenstafel Ridge, the 10th and 16th Battalions were ordered from Kitchener’s Woods. The 10th had already taken a heavy beating there and was down to 20 percent of its original strength. The two battalions managed to race across open ground and reinforce the other Canadian units, just in time to beat back another massed German attack. Fierce fighting raged everywhere along the line. Between Saint-Julien and Kitchener’s Woods, Canadian troops positioned between two farmhouses beat back repeated enemy attacks. Seeing that sheer numbers and poison gas alone could not break the Canadian line, the Germans turned to their numerically superior artillery, subjecting the Canadians to a horrific shelling.

The Situation Turns Desperate for the Canadians at Gravenstafel Ridge

With the Germans now firing at them from three sides, it was becoming painfully clear to the Canadian troops on Gravenstafel Ridge that they were in a desperate situation. Rifles jamming, ammunition running low, and the dead bodies of their comrades piling up around them, the stubborn defenders at the base of the ridge attempted to fight their way through the Germans in small groups. The survivors of the 7th Battalion, positioned northeast of Saint-Julien, were greatly helped in their escape efforts by Lieutenant Donald Bellew and Sergeant Hugh Peerless, who covered the retreat with Colt machine guns. Letting the Germans get within 100 yards, the two unleashed a telling volley. The Germans resolutely continued their attacking. Peerless was killed and Bellew wounded, but the indomitable lieutenant was not done yet. He continued to man his machine gun until it was out of ammunition, then disabled it. Next he picked up a bayoneted rifle and took on the swarming Germans in hand-to-hand combat. Finally overwhelmed, Bellew was taken prisoner. He would later receive the Victoria Cross for his exploits. The fellow Canadians he had helped to escape linked up with the 14th and 15th Battalions and established a new defensive line 300 yards in the rear.

Saint-Julien still remained in Canadian hands, but not for long. The three companies defending the town took a terrific pounding from German artillery, then fought a wicked street fight with 12 enemy battalions before being swept away. By 3 pm, the Germans had complete control of the town, and the handful of Canadians still alive were captured.

A Gap Widens in the Canadian Line

Brig. Gen. Richard Turner, commanding the 3rd Brigade, ordered his troops to fall back to the General Headquarters Line along the Saint Jean-Poelcappelle road. It was a grievous mistake by Turner, who somehow had misinterpreted the simple order to “hold your line.” Turner took this to mean the GHQ line. Besides causing hundreds of new Canadian casualties, the mistaken withdrawal opened a two-and-a-half-mile gap between the 3rd Brigade’s original trenches and the GHQ line. Only a handful of Canadians remained in the gap, including the beleaguered defenders of Gravenstafel Ridge.

General Arthur Currie, in command of the 2nd Brigade, continued to hold Gravenstafel Ridge, but unless reinforcements arrived soon he would have to retire. Fresh British troops were nearby, but they had been ordered to stay in the rear. Currie needed these men, and he personally headed to the rear to get them. The ever-punctilious British officers would not move their units without written orders, however, and Currie headed over to the British 27th Division headquarters to get the necessary pieces of paper. Once there, he had a fiery run-in with Maj. Gen. Thomas Snow, the British commander. Currie informed Snow in no uncertain terms that his men were barely hanging on and were in desperate need of reinforcements. Snow was unmoved. He verbally abused Currie for not holding the line on his own. On his way back to the 2nd Brigade, Currie managed to round up a few stragglers, but for the most part the Canadians holding Gravenstafel Ridge remained unsupported.

Despite Snow’s blustery words to Currie, the British commander eventually ordered reinforcements to assist the Canadians. The 12th Suffolk and 12th London Ranger Regiments headed toward the gap Turner inadvertently had caused. More British troops began arriving to reinforce the 3rd Brigade at Fourtin in hope of stopping the Germans from reaching the GHQ line. British troops from the York and Durham Brigade ran headlong into advancing Germans near Saint-Julien. With the help of accurate Canadian artillery support, the British forces routed the Germans, who hastily evacuated the town, fearing that they were up against a major Allied advance. They withdrew to higher ground to the north.

The Brits and Canadians, Outnumbered 3 to 1, Make Another Attempt At The Ridge

Turner was still determined to hold the GHQ line. At 7 pm, he ordered the 1st Royal Irish Regiment and two battalions from the York and Durham Brigade to fall back, thus reopening the very gap they had just closed. General Alderson finally caught on to Turner’s mistaken interpretation of the order to “hold your line,” but by now it was too dark to attempt to retake the lost ground. Both sides settled in for the night. The British and Canadians, though outnumbered three-to-one, still held on, but Currie’s precarious position on Gravenstafel Ridge, with his left flank in the air, seemed likely to fall at first light. Other Canadian defensive positions were not much better off.

Persuaded by the French—who mistakenly thought the Germans were outnumbered—to mount a counterattack, the British and Canadians agreed to attack at 3:30 am. Their intention was to recapture Saint-Julien and “driv[e] the enemy in that neighborhood as far north as possible.” Brig. Gen. Charles Hull, commanding the British 10th Brigade, was to lead the assault. The ensuing attack on the morning of the 25th was an abysmal failure. To begin with, the attack was rescheduled for an hour later, but the supporting artillery was unaware of the delay and opened up at the original time, thus alerting the Germans to the planned assault and announcing that Saint-Julien was no longer occupied by Allied troops. The Germans immediately headed into the empty town. Further, only five British battalions were slated to take part in the charge instead of the previously planned force of 15 combined British and Canadian battalions.

It was not until 5:30 am that the chosen battalions moved into position. Each battalion then attacked on its own, piecemeal-style, and was slaughtered by German machine guns. Lieutenant Walter Critchley of the Canadian 10th Battalion watching the attack later commented, “I have never seen such a slaughter in my life … they were lined up in a long line, straight up[,] and the Hun opened up on them with machine guns. They were just raked down. It was pathetic.” By 7 am, the misbegotten attack was over, at the cost of 2,419 dead and wounded Tommies. The bloodied remnants of the 10th Brigade fell back to the Canadian lines and filled in the gaps.

Yet Another All-Out Assault: A Month of Fighting

The Canadians, however, still remained vulnerable. German artillery pounded away while its infantry attacked both the British 28th Division on the right and the Canadian 1st Division on the left. The attacks were beaten back, but the Germans did manage to hold on to a 60-yard stretch of Allied trench. The Canadians were barely hanging on. Through yet another misunderstanding, Alderson believed that Gravenstafel Ridge had fallen. Therefore, instead of ordering Snow to send much-needed reinforcements to the ridge, he ordered the English general to set up a second line half a mile behind the ridge to stop the supposedly advancing Germans. Once more the Canadians were on their own.

Thousands of German troops then made another all-out assault on the Allied position in front of the ridge. The defenders fought back valiantly, but were overpowered by sheer numbers. The Canadians still clung to the ridge itself, but the situation was deteriorating by the minute. Currie and his battalion commanders reluctantly decided to abandon the ridge. Under cover of darkness the Canadians withdrew from the ridge and fell back to the new British line. Unfortunately, the British were not there. Fearing another attack on his division, Snow had simply refused to move. Meanwhile, the British troops on Gravenstafel Ridge refused to withdraw without written orders. Once again left in the lurch, the Canadians decided to turn around and rejoin their British comrades on the ridge.

Relief finally came for the beleaguered Canadians the next morning when they were ordered out of the line. Rest and hot food awaited them behind the lines, while fresh British troops moved in and took over their positions. It had been a bloody four-day baptism of fire for the Canadian 1st Division. Half its men, some 6,036, were casualties. Nevertheless, in its first battle the untested division had helped stave off a major Allied disaster. Fighting would continue for the Ypres Salient for another month, but the immediate threat of a decisive German breakthrough had been thwarted. British Field Marshal Sir John French realized what a close call it had been, and he paid full tribute to his North American cousins. “The Canadians,” he wrote, “held their ground with a magnificent display of tenacity and courage; and it is not too much to say that the bearing and conduct of these splendid troops averted a disaster which might have been attended with the most serious consequences.” The Canadians themselves were more modest about their exploits. Private George Patrick of the 2nd Battalion commented, “No one had any idea of getting out. We didn’t know enough about it to know that we were licked. We went in there and were going to stay there, and that was that.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments