by William E. Welsh

The soldiers of the two armies at Fort Donelson awoke on the morning of February 15, 1862, to another frigid morning. Fresh snow blanketed the hills and ravines along the Cumberland River and the trees were encased in ice. The men had no time to ruminate about the beauty of the winter landscape for both sides had important work to do. Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s 27,500 men were determined to keep the Confederates bottled up to force their surrender. Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd’s 17,500-strong Confederate army was determined to break out and march south to join other Confederates forces concentrating at Nashville.

[text_ad]

Two other Confederate generals, Brig. Gen. Simon B. Buckner and Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow, drew up plans the night before with Floyd for a break out to the east. It was a wonder that they agreed on anything as Buckner and Pillow despised each other as a result of disagreements going back to the Mexican War. Pillow would spearhead the attack, and Buckner would strip troops from his lines to the west to support Pillow. The spirited Confederate cavalry commander, Lt. Col. Nathan B. Forrest, would threaten the Federal flank.

Nighttime Snowstorm Muffles the Sound of Confederates Preparing to Break Out

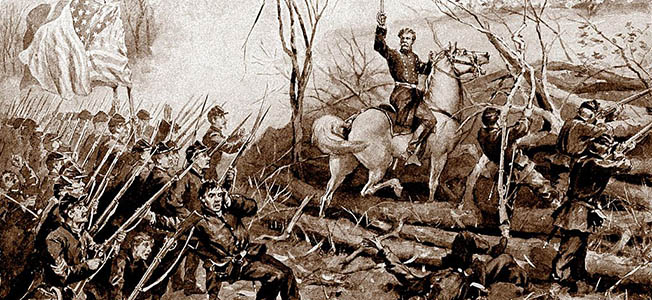

The tramping of Confederate regiments as they shifted into position for the attack the night before had been muffled by the screeching wind and driving snow. Pillow’s seven brigades surged forward on the clear morning after the snowfall against Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand’s unsuspecting division. The attack fell heaviest on the extreme right flank of the Union army with as many as seven Confederate brigades determined to push back the Union troops and open a corridor wide enough for the rest of the army to escape entrapment. During the three-hour fight, McClernand’s hapless Yankees retreated, in part because they ran low on cartridges for their rifle-muskets. The Confederates had captured six Union guns. They had a reason to be proud that frigid winter morning.

Pillow Loses His Nerve Shortly After Opening the Escape Hatch For the Army

At Noon there was a lull in the fighting. Buckner urged haste and told Pillow his men would help hold the escape corridor open. But Pillow began to fret about his exposed flank so much that he wanted to retreat. Buckner fumed. When Floyd arrived, Pillow asked him to settle the dispute. Floyd sided with Pillow, throwing away the victory that had been gained with the precious lives of those who had fallen bleeding in the snow. Stunned by the order to retreat, the graybacks complied and withdrew to their trenches.

Grant had not been present to witness the Confederate attack. He was conferring with Commodore Andrew H. Foote about coordination between river and land forces that morning. When word reached him of a Union retreat, Grant rushed back to his lines arriving at 1 PM. He rallied his troops telling them that the Confederates were trying to break out and that a counterattack was necessary to ensure they were unable to escape.

A Union Assault Overruns Rifle Pits on the Confederate Right

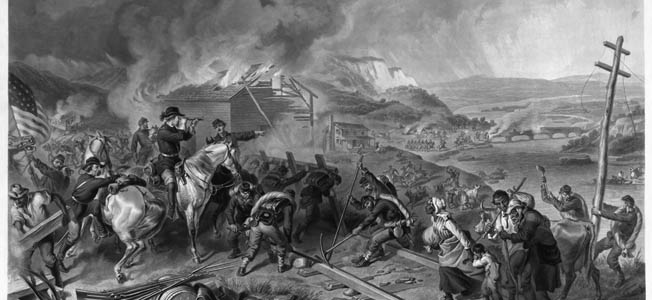

Grant correctly divined that the Rebel line would be thinnest to the west, so he ordered Brig. Gen. Charles Smith to attack the Rebel works to his front. Buckner had left one regiment to hold the rifle pits on the Confederate right flank. Smith’s division easily overran the position further unnerving Pillow and Floyd.

That night the two generals’ fear got the better of them. With no desire to be the first Confederate general to surrender, Floyd turned over command to Pillow and fled on a Confederate steamboat. Pillow then abdicated to Buckner and fled in a rowboat. Forrest, who was made of much sturdier material than Floyd or Pillow, led his cavalry to safety that night by riding through Lick Creek, which was not blocked by Union troops. Each of the cocky cavalrymen allowed an infantryman to ride behind him, thus carrying a small number of their fellow Confederates to safety.

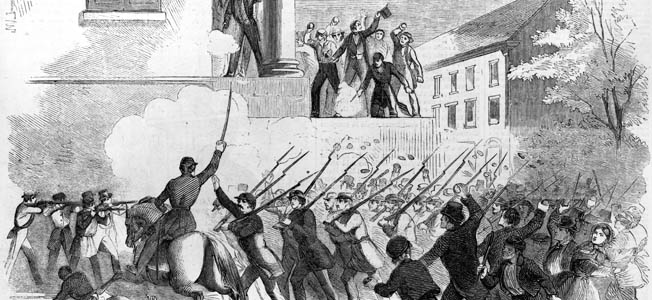

Believing the Confederate position untenable with Smith having seized high ground where artillery could be placed to bombard the interior of the fort, Buckner on February 16 sought surrender terms from Grant and waited at the Dover Hotel for Grant’s reply. Grant threatened that if Bucker did not agree to “an unconditional and immediate surrender” then Union forces would “move immediately upon your works.” For his tough stance, Grant immediately became a national hero in the North.

Directions from Nashville to Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson National Battlefield is located about 80 miles northwest of Nashville. If driving from Nashville, take I-24 north to State Route 374 west to State Route 79 south. The visitor center is one mile west of Dover.

The best place to start your tour of the battlefield is the visitor center, which is open daily except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. Rangers and volunteers can help you tailor your visit to your desires and also answer questions about the park and the chronology of events.

Driving Tour Captures the Scenes of Both Land and River Fights

An 11-stop driving tour will take you to the main sites within the park. Several stops merit mention. Stop two is the entrance to Fort Donelson. Confederate soldiers and slaves built the 15-acre earthen fort in seven months. The 10-foot-high walls of the fort were made of logs and earth. The fort’s irregular lines ran along the ridges a short distance back from the river. The fort’s primary purpose was to protect the water batteries guarding the Cumberland River.

Stop four is the site of the lower river batteries where green Confederate artillerymen manning the lower river batteries contested the attack of Foote’s small flotilla, comprising four ironclad and two wooden gunboats, on February 14. Foote probably could have destroyed the Confederate batteries if he fought them from a distance, since his guns had a longer range, but he was overconfident and sought to pummel them at close range. The result was that several of his boats were disabled, including his flagship, the St. Louis. The heavy exchange of artillery fire could be heard 35 miles away that day. Be sure to take time to enjoy the marvelous view of the Cumberland River while at this stop.

Stop five is the site of Smith’s attack on the Confederate right flank. Smith wanted his men to charge the Confederates, so he ordered them to fix bayonets and remove the percussion caps from their rifles that were used to ignite the cartridges. Spearheading the Union attack was Colonel James Tuttle’s 2nd Iowa Regiment. Smith’s division easily overran Colonel John Head’s 30th Tennessee securing the key high ground for Grant.

Stop Ten: Where Buckner Surrendered 13,000 Confederates to Grant

Stop Ten is the site of the Dover Hotel where the surrender was signed. Some of the Confederates had managed to sneak out the night before the surrender, either with Forrest’s cavalry or by other means, and therefore Buckner surrendered about 13,000 men to Grant. The prisoners were sent North, but most ultimately were exchanged in September 1862.

In addition to the Cumberland River, a couple of other compelling photographic subjects are the tall monument to Confederate soldiers at Stop One and the Dover Hotel at Stop Ten, which bears the distinction of being the only original structure still standing that served as the site of a major surrender in the American Civil War.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments