by William E. Welsh

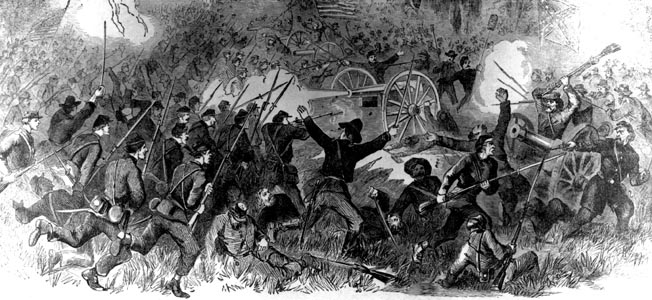

Gray waves of infantry emerging from the dark woods on both sides of the Orange Turnpike stampeded startled Yankees on the Federal right flank on May 2, 1863. One of the Union positions jeopardized by Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s flank attack was the artillery park at Hazel Grove.

[text_ad]

The Confederates were “rushing through and through my battery, overturning guns and limbers, smashing my caissons, and trampling my horse-holders under them,” wrote a disheartened Union artillery officer. Not all of the guns were overrun. Some Yankee gunners fired canister at point-blank range into Georgians trying to overrun their position.

Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles, commander of the Union III Corps, had approximately 22 guns posted at Hazel Grove. As darkness engulfed the battlefield, Sickles strived to consolidate his corps before it was cut off by Confederate forces converging on it. Somehow in the black of night he pulled his forward elements back from Catharine Furnace to Hazel Grove before dawn.

Order to Abandon Hazel Grove Unravels Union Position

Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. Joe Hooker, whose confidence returned during the night following Jackson’s sledgehammer attack of the previous afternoon, summoned Sickles to his headquarters at the Chancellor House before dawn on May 3. Fearing that Sickles’ salient at Hazel Grove would be assailed from both sides, he ordered him to withdraw to Fairview on the Orange Plank Road. It was a major blunder. Hooker was conceding high ground perfect for artillery to the enemy without a fight.

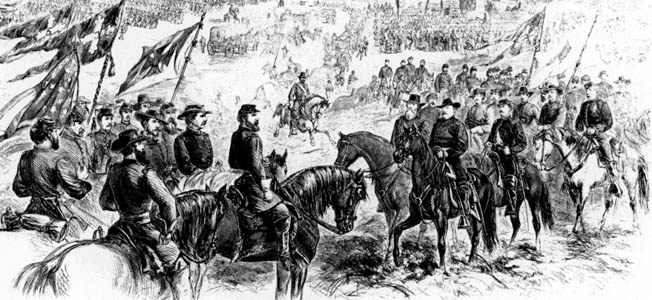

For the morning of May 3, Lee told Maj. Gen. James E.B. Stuart to take command of Jackson’s corps following Stonewall’s wounding by friendly fire the previous night. As soon as Rebel infantry secured Hazel Grove that morning, Stuart ordered his artillery chief to put as many guns in action on the ridge as possible.

“A beautiful position for artillery”

Hazel Grove was “a beautiful position for artillery, an open grassy ridge some 400 yards long, extending northeast and southwest,” wrote Colonel Edward P. Alexander, the artillery reserve commander responsible for massing Rebel guns at Hazel Grove. Once the infantry had cleared the ridge, “General Stuart…sent me word to immediately crown the hill with 30 guns,” Alexander wrote. “They were close at hand, and all ready, and it was done very quickly.”

Solid shot streaked from the Rebel guns into Fairview and even as far as the Chancellor House. “Some of our shells set fire to the big Chancellorsville House itself, and the conflagration made a striking scene with our shells still bursting all about it,” wrote Alexander.

Hooker failed to resupply his cannoneers in the ensuing duel between Union guns at Fairview and Confederate guns at Hazel Grove. With the support of the guns at Hazel Grove, Confederate infantry seized the Fairview and Chancellorsville clearings. By late morning Hooker’s army was in full retreat toward U.S. Ford on the Rapidan River.

Make Time to Drive Jackson’s Trail

Hazel Grove, which today bristles with period cannon, is one of 10 key sites at the Chancellorsville battlefield, which is part of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park administered by the National Park Service.

Visitors’ first stop at Chancellorsville should be the visitor center at 9001 Plank Road. The center features exhibits, a bookstore, and a short film about the campaign. A short trail leads to the site where Jackson was tragically wounded.

Although all of the sites on the driving tour are worth visiting, the must-see sites are the Chancellor House Site, Hazel Grove, and Fairview. What’s more, it is worth carving out enough time to drive Jackson Trail, a gravel road that follows the route of Jackson’s II Corps on its famous flank march.

While visiting the park, contemplate how on May 2 the Confederacy’s fortunes soared as the Rebels headed toward a glorious victory, and then rapidly plummeted with the wounding of a remarkably gifted, irreplaceable general.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments