by Eric Niderost

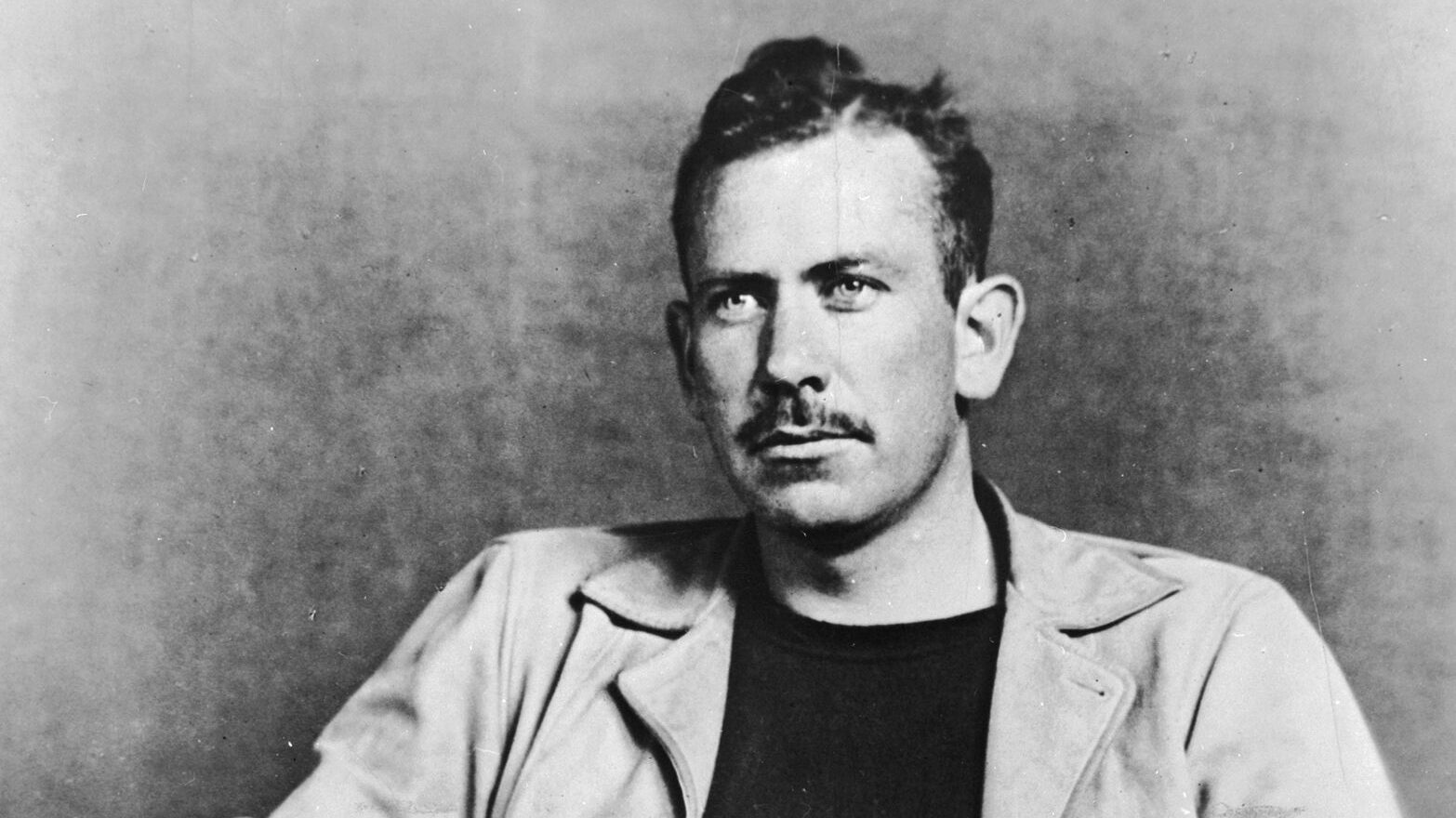

Walter Cronkite is the acknowledged dean of American journalists, an icon whose distinguished career spanned 60 years. Cronkite is best known as the anchorman and managing editor of The CBS Evening News, a position he occupied from 1962 to 1981. The late 20th century was a tumultuous time, crowded with many world-shaking events. In an era beset by fears of nuclear war and the threat of political and social upheaval, Cronkite was a reassuring presence.

During his 30 years as a television reporter and anchor, he was an avuncular figure whose passion for objectivity, basic decency, and fatherly—or grandfatherly—persona struck a responsive chord with the American public. Even his manner of speaking was reassuring. Who can forget the distinctively deep voice, resonating with the measured cadences of a veteran broadcaster? When he ended each newscast with “And that’s the way it is,” it was less a tagline than a statement of simple fact. You knew he reported the facts as truthfully and objectively as he could.

Most people remember Walter Cronkite as a television newsman, and earlier in his career as a print journalist and even a radio sports announcer. But few people today realize Cronkite was a correspondent in World War II. Assigned to the European theater, he personally witnessed the conflict on land, air, and sea.

A Fledgling Reporter in Texas

Walter Leland Cronkite, Jr. was born in St Joseph, Mo. on November 4, 1916, the son of a dentist. The family soon moved to Houston, Texas, where Dr. Cronkite had received an offer to teach at a dental college. Cronkite became interested in journalism while attending the University of Texas at Austin from 1933 to 1935. Since Austin is the state capital, he landed part-time work as a copy boy and sometime reporter for the capital bureaus of several newspapers. He even tried his hand at radio, reporting sports scores for local station KNOW.

For a time, the fledgling reporter shunted between radio and print work. It was a proud moment for the young scribe when he got a job at the Houston Press. Cronkite was proud of the fact he had a desk in the city room, and that he was making $15 a week—a good salary for Depression-era America.

In 1939, a maturing Cronkite joined the United Press, or UP. Though America was at peace and still largely isolationist, Hitler’s aggressive moves were making front page news. Japan’s brutal conquest of China was also being avidly followed by millions of American readers. Cronkite was busy at UP’s foreign desk in New York, but soon he would be doing more than gathering and interpreting overseas news reports.

Cronkite’s Start Covering World War II

When Japan attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, the nation found itself fighting a two-front war. It was decreed that civilian journalists would be given the unofficial status of officers, at least for the duration. They would wear officers’ uniforms, though without branch of service designations or badges of rank. To underscore their affiliation with the fourth estate, war correspondents would wear a large green brassard with a large letter “C,” the identification to be worn on the left arm.

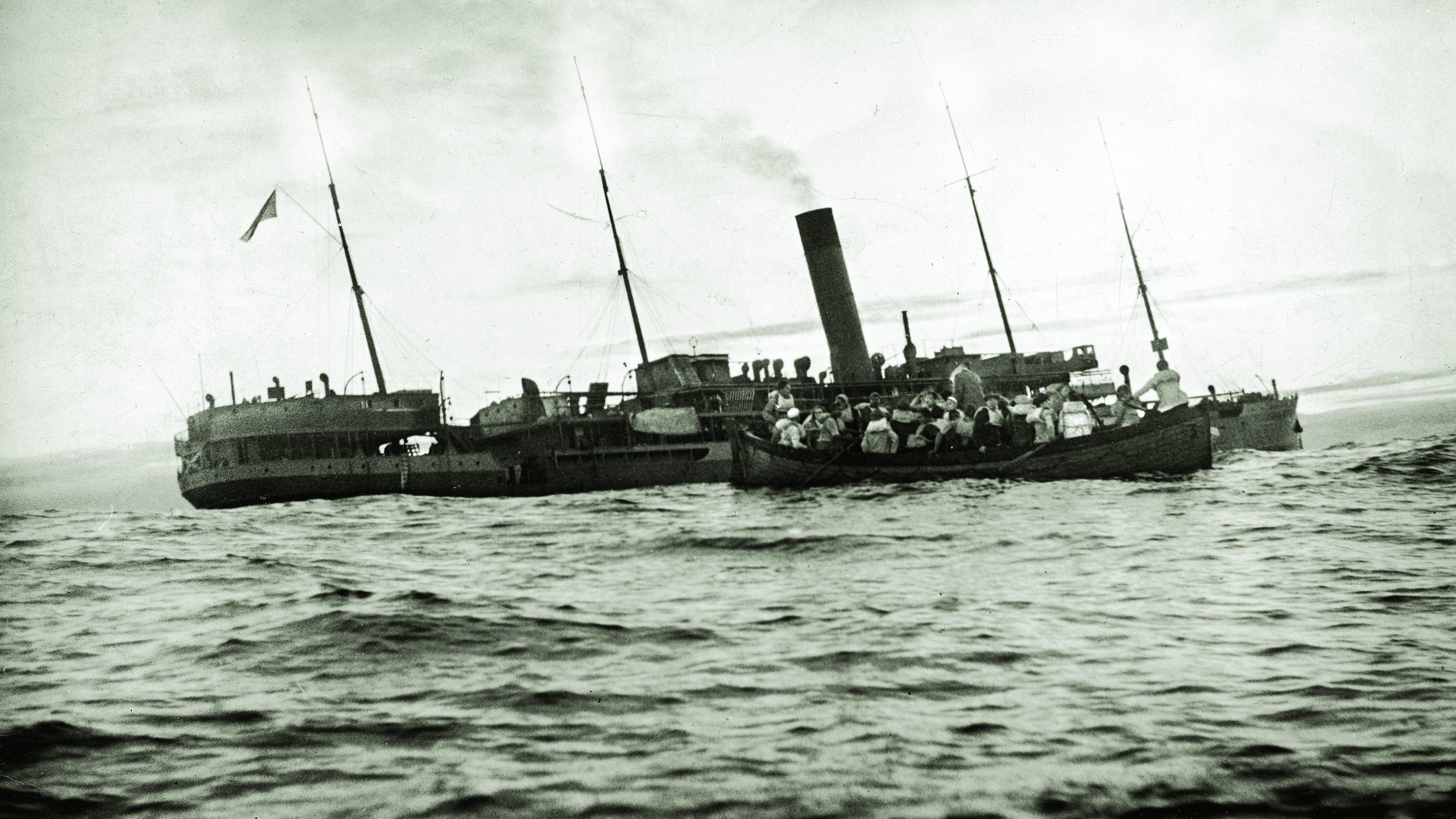

Cronkite found himself in uniform and assigned to cover the North Atlantic convoys that were shipping vital war materiel to Britain. Once, early in the war, Cronkite was being shown around the battleship Arkansas. When he got to the wardroom, officers began to ask his religious affiliation. Puzzled but friendly, Cronkite jocularly referred to himself as a “sort of jackass Episcopalian.” Pressed further, the reporter admitted he did not go to services that frequently. Then the truth dawned: the officers had mistaken the “C” on Cronkite’s uniform for “chaplain!”

In September 1942, Cronkite joined a fleet that sailed from Norfolk, Virginia. It was part of the great Anglo-American invasion of North Africa. The primary targets were North African port cities in Morocco and Algeria, then controlled by Vichy France. He reported aboard the USS Texas, an old battleship well past its prime. The aging leviathan had a dual mission. It was supposed to take the small coastal town of Port Lyautey and its arsenal, and also transport a secret broadcasting unit appropriately known as Clandestine Radio Maroc.

The men of Clandestine Radio Maroc were a curious amalgam of reservists and civilians. There were newspapermen in the Hemingway mold, and bohemians who had once sampled the delights of Paris and its “moveable feast.” There were also upper class “social register” types and foreign businessmen. All had been recruited by the Office of War Information for their fluency in French.

In the fall of 1942, the Allied invasion of North Africa was well underway. The USS Texas arrived at its destination and trained its 14-inch guns on Port Lyautey. Its first ear-splitting salvo was an impressive one, but shook the old battleship to its core. This artillery barrage was to have been followed by a verbal one, namely a broadcast by Clandestine Radio Maroc exhorting the colonial French to join the Allied cause, along with a message from President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Unfortunately, the message fell on deaf ears, and not because of the shelling, but because Clandestine Radio Maroc had been knocked off the air by the concussion of the Texas’s guns. Clandestine Radio Maroc eventually was put ashore, and none the worse for wear—save for a little egg on its face.

Journalists Push to Be Allowed to Accompany Air Crews

Walter Cronkite made it back to the U.S. but didn’t linger long. He was soon bound for Britain, where the U.S. Army Air Forces were establishing bases in the heart of the beleaguered island. In 1943-1944 the so-called “second front,” the Allied invasion of France, was still in the future. For the Western Allies, strategic bombing was the only way to carry the war into the heart of enemy territory. The American Eighth Air Force’s Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators conducted daylight raids, while the Royal Air Force bombed targets at night.

Cronkite came to know the airmen intimately, most in their 20s and so young they seemed mere boys. They became familiar figures in Britain, distinctive in their leather flight jackets and “20 mission” crush caps. They had a job to do, and they did it with skill and devotion, but sometimes their lives were cut tragically short.

War correspondents did not want to be passive observers on the ground, recording events after the fact. They wanted to actually accompany air crews on their missions. The Army Air Forces were initially reluctant to expose civilians to danger, but at last relented. The correspondents would be required to learn the basics at the Combat Crew Replacement Center.

Walter Cronkite and his colleagues learned aircraft identification and high altitude survival, just as if they were new bomber recruits. They also learned aerial gunnery and how to handle a .50 caliber machine gun. This was a violation of the Geneva Convention, which required all noncombatants to be unarmed. The Army Air Forces trained the correspondents in gunnery so they could lend a hand in combat if necessary. If a plane was shot down and its crew forced to bail out, the Germans would not know who fired any guns.

‘The Writing Sixty-Ninth’

The little band of correspondents chosen to accompany the bombers were soon dubbed “the Writing Sixty-Ninth” by an over-imaginative air force publicist. It was a pun that takes its inspiration from the “Fighting 69th,” a distinguished American unit in World War I. Besides Walter Cronkite, the group included Andy Rooney of the Army newspaper Stars and Stripes, and future commentator and resident “curmudgeon” on television’s Sixty Minutes.

Five “Writing Sixty-Ninth” correspondents were picked for their first mission. The assignment was to bomb the submarine pens at Wilhelmshaven, Germany. This was no milk run, but an extremely hazardous mission. Cronkite was aboard a B-17 Flying Fortress, in the plane’s nose with the navigator and bombardier. This was the period when Allied fighters did not have the range to protect the bombers all the way to Germany. The B-17s and B-24s had to fly though a hurricane of flak and swarms of Luftwaffe fighters to reach their target.

In his 1996 book A Reporter’s Life, Cronkite wrote about the mission, recalling he tried his hand at firing a .50 caliber machine gun. “I fired at every German fighter that came into the neighborhood. I don’t think I hit any, but I’d like to think I scared a couple of those pilots … I could hardly get out of the plane when we got back—I was up to my hips in spent .50 caliber shells.”

The Wilhelmshaven raid was a costly one. Out of 66 planes, thirteen did not return–a loss of almost 20 percent. One of the casualties was Bob Post of the New York Times. Cronkite summed up the experience in an article he wrote for the UP, saying it was an “assignment to hell, a hell at 17,000 feet, a hell of bursting flak and screaming fighter planes, of burning Forts and hurtling bombs.”

Cronkite at D-Day

In the early months of 1944, the Allies were gearing up for the long-awaited invasion of German-occupied France. The date and location of the landings were the most closely guarded secrets of the war. As D-Day approached, Cronkite was initially assigned to stay in London and write the anticipated lead story. When General Dwight D. Eisenhower gave the green light, Cronkite was suddenly told he would accompany a bombing mission at Omaha Beach.

Cronkite’s plane was to destroy some German artillery emplacements that commanded the beach. Unfortunately, the mission proved a washout—a highly dangerous washout at that. The cloud cover was so thick that there was no way of getting an accurate fix on the target. The risk was too great that the plane would end up bombing Allied troops as they came ashore. The mission was aborted, and the bomber headed home. The pilot had to touch down in the fog with a belly full of armed bombs, no easy task.

Cronkite would visit Omaha a few days after the beach was secured, but was then summoned back to London. A plan was in the works to liberate Paris by a coup de main. Allied paratroops would drop behind enemy lines, parachuting into the Rambouillet Forest just north of the French capital. It was a risky and bold maneuver, but the battle front advanced so rapidly that the mission was scrubbed as unnecessary. General Jacques Philippe Leclerc’s French Second Armored Division soon liberated Paris.

A Close Call with a V-1

Although the Paris airborne drop was aborted, Cronkite remained on call for any other airborne operation that might be attempted. While he waited for his next assignment, Cronkite got a taste of what the British were enduring on the home front. In the summer of 1944, Hitler was placing great faith in his so-called vengeance weapons to turn the tide. One of these was the V-1 flying bomb, equipped with wings and a gyroscopic piloting device to guide it to the target.

Cronkite was at his quarters at Buckingham Gate Road in London when one of the buzz bombs suddenly struck nearby. The air raid sirens wailed, but the flying bomb’s noisy engine gave an even clearer indication of danger. When the engine sound cut, it was a signal of the bomb’s final earthward plunge. Warned by the noise, Cronkite ducked away from his window just as the bomb exploded. The building shuddered in protest, the near-miss concussion creating clouds of billowing dust, broken plumbing, and shattered glass.

Cronkite was unhurt, though probably a bit shaken. The bomb had hit the nearby Guards Chapel just as a Sunday service was underway. Many officers and some wives were killed in the blast.

Operation Market-Garden

In September 1944, Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery conceived the idea of a massive Allied airborne operation to seize a series of bridges in Holland. The key bridge would be the one over the Lower Rhine at Arnhem, the last major natural obstacle on the road to Germany. Once the bridges were taken, the British army was to link up with the airborne forces and push on into the Reich. With luck, the Allies would be able to push into the very heart of Germany’s industrial Ruhr region.

The operation, codenamed Market-Garden, proved an over-ambitious near-disaster. The British First Airborne Division managed to drop into Arnhem, only to be counterattacked by elements of the German II SS Panzer Corps. Lt. Col. John Frost of the Second Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, made it to Arnhem Bridge, seizing the northern anchorage, but the regiment was quickly surrounded and cut off by superior German forces. After several days of heroic defense, they were forced to surrender.

After an epic battle, a ragged British First Airborne was forced to retreat back over the Rhine. Ironically, other Allied units, particularly the U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne, managed to take their own bridge objectives intact, though not without heavy cost. Cronkite was assigned to the 101st Airborne, with units ordered to take a stretch of road just south of Eindhoven.

On September 17, 1944, Cronkite was aboard a Waco glider skimming above Holland on the end of a tow rope. Once the towing C-47 dropped its “cargo,” the Waco plunged like a stone, but then, just when all seemed lost, it leveled off and glided above the flat Dutch countryside. It seems the Waco pilot was a good one, because the seemingly fatal plunge was a technique to evade enemy ground fire.

The landing was a rough one—most glider landings were rough—and helmets flew in every direction as the glider did a half-flip in a potato patch. Cronkite was with a headquarters company of about 14 men, and as he and his companions dug themselves out of the soft Dutch soil, other gliders thudded to earth. Sporadic German gunfire greeted them.

According to Cronkite’s own account, he grabbed his helmet and started making his way to the prearranged rendezvous point, a drainage ditch that was supposed to be in the area. The Germans were alert, and sporadic firing broke the silence of a peaceful countryside.

As he ran along, he noticed he was being followed by several paratroopers. “Hey, Lieutenant,” they called, “are you sure we’re going in the right direction?” They had been fooled by Cronkite’s helmet, which sported the vertical officer’s white stripe in the back.

When Cronkite explained he was not an officer but a war correspondent, he was greeted by a barrage of four-lettered oaths. At least he was not leading them astray—the rendezvous was in the direction he was going.

Later, the 101st Airborne had to keep open the narrow corridor to Arnhem that the Allies had won at the cost of so much blood and treasure. Casualties were heavy, causing the road to be dubbed “Hell’s Highway.” The situation was fluid in the extreme, with the Germans sometimes managing to briefly cut the highway under the cover of darkness. Cronkite had a jeep and a GI driver to take him around, but the increased mobility got him into trouble.

One night, Cronkite and his driver paused for a moment on the side of the road. They could hear the metallic clank of tank treads, but decided to sit tight. Suddenly, five German panzers appeared on the road, all heading in the direction of Cronkite’s jeep. Fight or flee? There was no time to flee, and fighting five tanks seemed foolhardy in the circumstances. They just sat tight, and the panzers rumbled right by them. Some of the black-uniformed tankers shouted and waved greetings, perhaps mistaking Cronkite and his driver for Germans in the semi-dark. The tanks passed, allowing Cronkite to breathe again.

Cronkite was in Brussels when he received word of the German offensive later known as the Battle of the Bulge. The first few days were chaos, and roads were clogged with retreating American units. To reach the front Cronkite had to navigate through a flood of stampeding soldiers, trucks, and other vehicles like a salmon going upstream. He finally reached Luxembourg City, which he used as his reporting base for the rest of the battle.

A Brush With Patton’s Temper

The intrepid reporter also had a run-in with one of the most famous generals of the war, George S. Patton, Jr. Patton’s Third Army was famed for its battle prowess, and the general ran a tight ship. Rules and regulations were to be obeyed without question. One of Patton’s iron-clad dictums was that personnel were to wear helmets at all times.

One day Cronkite was being driven in his jeep when the vehicle encountered a patch of rough road. The jolting grew so bad, the correspondent’s helmet bounced off and catapulted into a field. The driver hit the brakes and jumped out to retrieve the missing headgear only to see a nearby sign that read “DANGER, MINES.” No helmet was worth risking life and limb, so Cronkite and his companion drove on.

A cluster of jeeps appeared, the lead vehicle with a flashing red light and a screeching siren. It was Patton’s convoy, and the general himself was present with his entourage. Patton’s eagle eye had seen the bare-headed Cronkite, and his jeep stopped just ahead to reprimand the brazen offender. A full colonel jumped out of the general’s jeep, shouting for Cronkite’s name, rank, and serial number.

Irritated at the colonel’s brash manner, the reporter explained his helmet was lost in a minefield. Besides, he was not a soldier, but a member of the press, a war correspondent. There was not much that the colonel could do to a civilian, so he turned on his heel and sheepishly reported back to the general. As Cronkite later recalled, “Patton uttered a single word that might have been an expletive well-known among his troops.” Patton, who knew how to accept defeat as well as victory, drove on without further comment.

Revulsion at the Nuremberg Trials

Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945, but there was an interesting postscript to Cronkite’s war experiences. He covered the trial of notorious Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg, an experience that gave him a sense of real revulsion. Earlier, he had interviewed a minor-league Dutch collaborator named Anton Mussert. The cowering quisling, fat and sweating like a pig, vehemently denied he was a Nazi stooge. As Cronkite left, Mussart gave himself away by involuntarily shouting “Heil” and raising his arm in the Nazi salute. He was hanged as a war criminal.

Cronkite had nothing but contempt for the 21 Nuremberg defendants, a contempt that deepened as the damning evidence was presented in court. As he later put it, “ … subconsciously, I suppose … I thought them lower than the dirt on the street … ”

A Long and Storied Career

In the course of his career, Cronkite has come into contact with many U.S. presidents. He caught a glimpse of Franklin D. Roosevelt during the 1928 Democratic National Convention when it was held in his hometown of Houston. Later, as a reporter, he would occasionally attend one of Roosevelt’s informal press conferences in the Oval Office. The President would hold court, freely answering questions from a huddle of reporters who literally crowded around his desk.

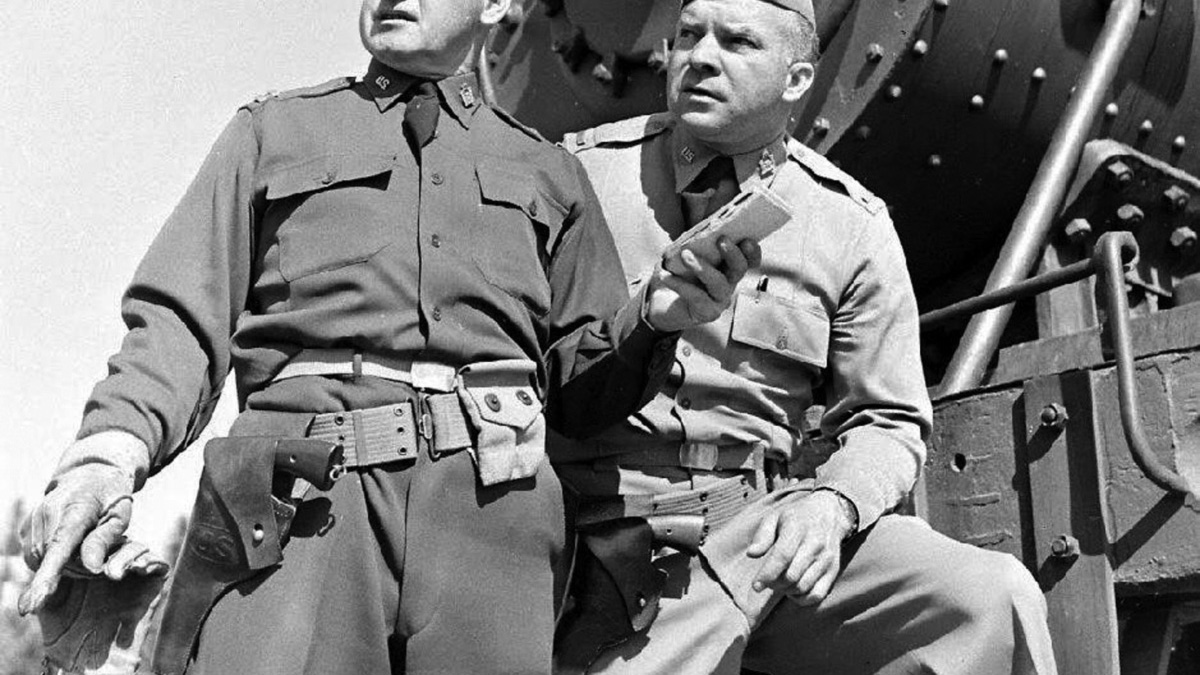

In 1963, Cronkite even returned to the Normandy beaches to do a CBS special “D-Day Plus 20” with former President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The pair visited the various places associated with D-Day, including the room at Southhampton where he gave the invasion the go-ahead after careful deliberation, and the various landing beaches along the Normandy shores.

Walter Cronkite retired from The CBS Evening News in 1981, handing the anchor chair to Dan Rather. He still keeps quite active, touring the country and making various appearances, sometimes reporting for National Public Radio. Every New Year’s Day he hosts a program of Strauss music performed by the Vienna Philharmonic. On January 1, 2004, he celebrated his 20th anniversary with this special musical event. The Vienna Philharmonic presented Cronkite with a special medallion to mark the occasion, and to show their appreciation.

Author Eric Niderost is a veteran writer on historical topics. He works as a community college professor in Hayward, Cali.

Walter Conkite… the most Memorable reporter and correspondent of my age….passed away, July 17, 2009, in New York.