by William F. Floyd Jr.

On March 5, 1936, the new Supermarine Type 300 took off from Southampton, England. The plane would soon be called the Spitfire, and along with the Hawker Hurricane it would become Great Britain’s first line of defense. For those witnessing this historic event, it would have been hard to imagine that roughly 20 years earlier the Royal Air Force (RAF) was close to extinction.

After World War I, the Allies began dismantling their victorious war machine with hardly any thought for the future. In the Admiralty and the War Office there were powerful lobbies that wanted to see the end of the RAF as an independent organization, making it part of the Army and Navy. This did not occur largely due to the work of Chief of the Air Staff Air Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard.

The Man Behind the Plane

Reginald Joseph Mitchell is the man most closely associated with the development of the Supermarine Spitfire. In 1920, he was appointed chief engineer and designer on projects mainly concerning flying boats. The Spitfire was developed in response to a 1934 Air Ministry request calling for a high-performance fighter with eight wing-mounted .303-inch machine guns. The plane was to be designed around a 1,000 horsepower, 12-cylinder, liquid-cooled, Rolls-Royce PV 12 engine (later called the Merlin). The design was much more radical than that of the Hurricane.

The Supermarine Spitfire had a stressed-skin aluminum structure with elliptical wings and a thin airfoil that along with the Merlin’s two-stage supercharger gave the plane exceptional performance at high altitudes.

After a March 5, 1936, test flight and some minor modifications, the Type 300 was flown to Martlesham Heath in Suffolk to be evaluated by the Aeroplane Experimental Establishment. On June 10, the Air Ministry approved the name Spitfire. After spinning trials and further flight testing, the plane went back to Martlesham for full handling trials. The testing results far exceeded those specified by the ministry.

During this period the plane underwent several modifications. These included the replacement of the original Rolls-Royce Merlin engine with a Merlin F, which developed 1,045 horsepower, and the addition of a reflector sight and tail wheel.

Production in Full Swing: One Plane Per Week

The primary architect of the Supermarine Spitfire died of cancer on July 1, 1937, at the age of 42. He had labored under a great deal of pain while still working on a bomber project at the time of his death. Mitchell had shunned fame and any form of publicity for himself. Despite his exceptional ability, he was not widely known outside aviation circles. His position at Vickers-Marine was taken by Joseph Smith, who had been his assistant. Smith would now be responsible for all future Spitfire design and development.

On June 3, 1936, an order was given to Supermarine for 310 Spitfires. The order was part of the Air Force’s Expansion Scheme F, which called for 1,736 planes to be in service by 1939. The first Supermarine Spitfire to be accepted for RAF charge was K9792, which went to the Central Flying Establishment at RAF Cranwell for evaluation by instructors. The plane was approved, and deliveries continued at the rate of about one a week.

Other squadrons would slowly begin to receive the new fighter plane. During the spring and summer of 1939, as war with Germany began to look more inevitable, the newly equipped Spitfire squadrons trained intensively in air gunnery, dogfighting, and formations to simulate actual conditions.

The Battle of Britain Begins

The war in the skies above Great Britain began in earnest in July 1940. The Battle of Britain took its name from a speech given by Prime Minister Winston Churchill before the House of Commons. The battle was confined primarily to southeast and southern Great Britain. The Luftwaffe initiated the battle in preparation for Operation Seal Lion, the German invasion of Britain. The RAF did have certain advantages over the Luftwaffe. First, the British were fighting to protect their homeland.

Second, the British had a distinct advantage on the defensive as a result of a superb advanced warning system composed of Chain Home Radar Warning Stations and the Ground Observer Corps. Third, German pilots were hampered by their 410-mile operational limit.

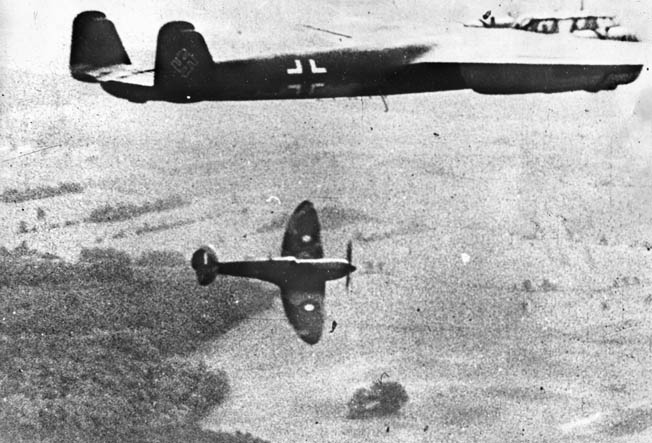

The main aircraft used against the Luftwaffe were the Hurricane MKI and the Supermarine Spitfire. Reichsmarschal Herman Göring, commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, laid out the aims for the planned air war with Britain. The Luftwaffe’s objectives included the destruction of British fighter aircraft, airfields, and factories. The first German attacks in July 1940 were aimed at destroying airfields, but this tactic was soon switched to bombing more strategic targets in an effort to lower British morale.

Outnumbered 10 to 1 in the Sky, but Morale Remained High

The strategy backfired as British morale remained high, and the reprieve given to the airfields gave the RAF the break it needed. The RAF initiated a massive repair program under the direction of Lord Beaverbrook that returned battle-damaged Spitfires and Hurricanes to service as soon as possible.

The RAF sent accident officers to crash sites to determine if the planes could be repaired. The repairs were performed by motor car companies that were referred to as Civilian Repair Units. On the other side of Lord Beaverbrook’s industrial empire was the manufacture of new planes. In August 1940, the British produced Spitfires and Hurricanes in record numbers.

The Germans had approximately 10,000 trained pilots in 1939, while British Fighter Command had 1,450 trained pilots. The fighting over London during this time was particularly savage. Hurricanes attacked bombers, and Supermarine Spitfires went after enemy fighters. During the battle, Fighter Command lost more than 500 pilots over southern England. On August 20, 1940, in an overcrowded House of Commons, Winston Churchill summed up his feelings about the RAF’s defense of the country by saying, “Never in the history of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

This article is featured in the November 2014 issue of

Military Heritage Magazine.

Order your copy today!

Superiority in the air was the task of the fighters, and they played a huge role in the eventual outcome of the war. In Western Europe, North Africa, the Mediterranean, the Far East, and the Pacific, the fighter plane seemed to hold things together when the outcome of World War II was still uncertain. The Spitfire played a major part in this effort.

RAF “Rodeos”

In early 1941, RAF Fighter Command decided to begin offensive operations against the Luftwaffe. The operations, which involved both Spitfire and Hurricane squadrons, became known as “Rodeos.” From May 1941, RAF pilots flying into France began to see a new model of Messerschmitt that was more than a match for the Hurricanes and Spitfires. The RAF squadrons began reequipping the Supermarine Spitfire MK V with a strengthened airframe and Merlin 45 engine, which was more than able to fight the Bf-109F on equal terms. However, in September 1941, events took a turn for the worse.

RAF pilots began to report that they were being attacked by an enemy fighter that they were not familiar with. This advanced German fighter was the Focke-Wulf Fw-190, a highly agile radial engine fighter, soon to be known as the “Butcher Bird” because of its combat prowess.

One of the most important uses of the Spitfire during the war was when Great Britain began supplying them to Russia for use on the Eastern Front. The Spitfire became operational in this theater of the war in September 1942, when it was used for reconnaissance against German shipping. On October 4, the Soviet ambassador in London requested additional Spitfires. The request was approved by Churchill, and another 187 Supermarine Spitfire Mk VBs were sent to Russia. The planes took part in the Russian counterattack that led to the destruction of the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad.

Suppressing Japan in the East

In 1942, the Japanese in Burma were opposed by a combination of American, Chinese, and British Commonwealth forces. The arrival of the Spitfire aided in preventing Japanese advances into China and India. By January 1944, six Spitfire squadrons played a part in achieving air superiority over western Burma.

Seafire was the name given to the naval version of the Spitfire. It saw most of its service in the Pacific and Far East. It formed part of a group hunting Japanese and German submarines. One problem with the Seafire was its short combat radius, which restricted its use to combat air patrols. In June 1945, auxiliary fuel tanks were added to the Seafire, increasing its combat range by 50 percent and allowing it to take part in offensive operations.

The British Supermarine Spitfire was probably the best known fighter plane during this period of history. As Churchill stated, it was the primary reason for Great Britain’s survival during the blitz of Great Britain by the Luftwaffe. At times, it had to be modified as new German planes came on line, but it continued to hold its own throughout the war. The pilots who flew the Spitfire in defense of Great Britain were some of the bravest of the brave, particularly early in the war when they were greatly outnumbered. Even the Germans agreed that the Spitfire was a worthy opponent.

Gunther Rall, a German ace who test flew captured Allied fighter planes, said that he preferred the Spitfire over all other fighter aircraft that he had flown. The Spitfire was in continuous production throughout the war with 22,800 produced. For many years after World War II, the Spitfire continued in service. It saw action in the Greek Civil War, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and in a later conflict was flown by both the Israelis and Egyptians. It also saw action in Korea in the early 1950s, and its popularity continued to remain high into the 1960s.

Originally Published October 20, 2014

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments