By Vince Hawkins

In 1814, as a consequence of her victory in the Napoleonic Wars, Great Britain was formally ceded the Dutch South African territory of Cape Colony. Thus more than 160 years of official Dutch influence in South Africa came to an end. But in that time the white colonists of Cape Colony, a mix of Dutch, German, and French, had evolved into a new and distinct people known as Boers or Afrikaners. The Boers, from the Dutch/German words meaning “farmer,” spoke Taal, a variation of 17th-century Dutch that later became known as Afrikaans. Essentially farmers and cattle herders, the Boers were a hardy, independent-minded people known for their dislike of governmental influence and their hostile, racist attitudes toward the black South Africans, particularly the Hottentots. These traits would form the basis of the conflicts that arose between the Boers and Great Britain.

In an effort to escape governmental influence and despite Dutch efforts to contain the colony, the Boers began to migrate farther away from the reach of authority, searching for new lands. This brought them into closer proximity with the Bantu nation, and led to near continuous conflict over territory and grazing rights. Never fond of the Dutch government, the Boers found themselves even less pleased with the new British government. The British attempted to put a stop to the fighting between Boers and black South Africans; they established policies designed to prevent whites from abusing the native population, particularly in regard to slavery.

The Boers, who felt that black South Africans were fit for nothing but slavery, and who operated under the concept that slavery was a personal affair, resented any policy that interfered with that belief. Troubles started by these policies came to a head when the British government abolished slavery and ordered the emancipation of all slaves in Cape Colony by December 1, 1834. While compensation was to be paid to the slave owners, the amount never equaled what was promised and many slave-owning farmers were ruined. In response, the Boers decided to move again, farther into the interior of the country and as far away from the British as they could. The Boers referred to this mass migration as the “Great Trek.”

By 1838 the Boers had established themselves between the Orange and Vaal Rivers and along the borders of Natal where they declared several small republics, among which was the Transvaal. In the process of their migration they came into conflict with another South African nation, the Zulu, and the usual series of white and black conflicts began again. In 1854 the Boers gained their independence from Britain with the establishment of the Orange Free State. For the next several decades the Boers managed to keep enough of a low profile that the British had no reason to encroach on their territory. The situation in the Transvaal, however, never very good to start with, grew progressively worse.

By 1880 British influence in the Transvaal had reached a state of intolerance among the Boers. The discovery of diamonds and gold in various parts of the area had led the British to annex parts of the region in 1867, despite the vehement protests of the Boers. The free-spirit lifestyle of the Boers, their refusal to pay taxes, and the constant infighting among their leaders resulted in near political anarchy and the emasculation of their government. To add to their problems, the Bapedi tribe and the Zulus were massing on the borders for an invasion.

The Boers Mustered Nearly 7,000 Men to Drive the Enemy From Their Homes

Further, despite the law the Boers were still practicing slavery, albeit hidden under a policy of “apprenticeship.” The law allowed orphaned black children to be provided for by apprenticing them. These children usually became “orphans” because the Boers killed their parents or they were kidnapped after a raid. Affairs in the Transvaal had reached such a state that the British believed they had no choice but to intercede to save the republic from complete disaster. Therefore, in April 1877, Britain annexed the Transvaal. By 1879, Boer distaste for British autonomy had led to open defiance of the Crown’s authority, and the British subsequently established fortified garrisons across the country to control a possible Boer uprising.

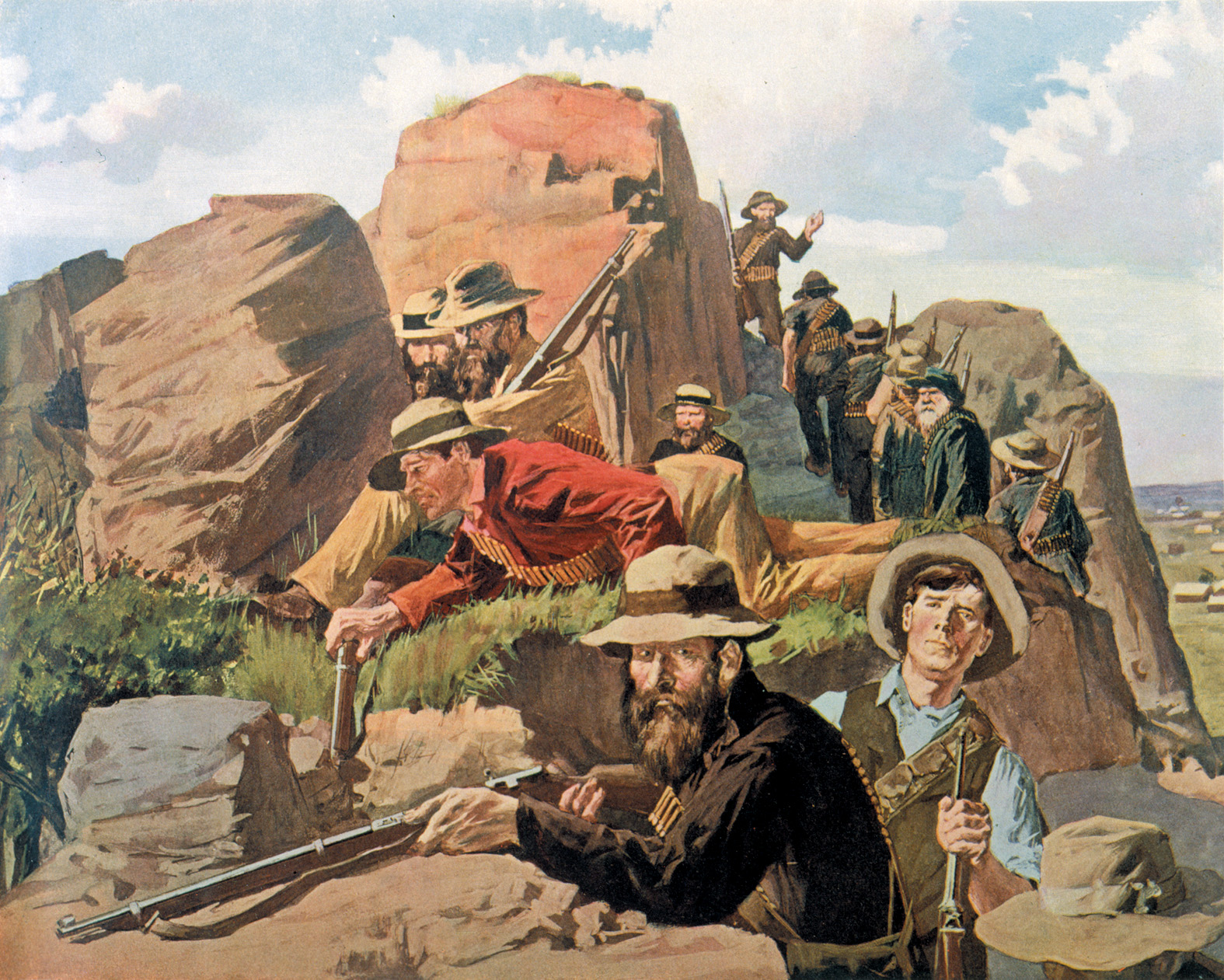

On December 16, 1880, their attempts to peaceably regain an independent status having been frustrated by the unyielding attitude of the British government, the Boers proclaimed a republic in the Transvaal. Almost immediately hostilities flared up as the Boers attacked any British troops who refused to evacuate the newly declared republic. The Boers, under the leadership of S.J. Paul Kruger and Petrus (“Piet”) Jacobus Joubert, had managed to muster an ad hoc force of nearly 7,000 men to drive the enemy from their home. On December 20, a British column on its way from its garrison at Lydenburg to the capital at Pretoria was ambushed at Bronkhorstspruit by a Boer commando unit (local militia) of some 250 men.

The column, under the command of Lt. Col. Philip R. Anstruther of the 94th Regiment of Foot, contained two companies of the 94th, totaling 268 officers and men, 3 women, and 34 wagons. Before Anstruther’s men could deploy from marching order into battle line the fight was over, leaving 56 soldiers and one of the women dead and 101 men wounded. With all of his officers killed or wounded, Anstruther, himself severely wounded, ordered the remainder of the column to surrender. The Boers claimed to have lost only two dead and five wounded. The shots fired at Bronkhorstspruit signaled the beginning of the First Anglo-Boer War.

Having taken the British by surprise and unprepared, the Boers moved quickly to follow up their first victory. British forces, strung out in small, isolated garrisons such as Lydenburg, Potchefstroom, and Marabastadt, were quickly surrounded and put under siege. Leaving just enough men to keep the British forces trapped in their outposts, Commandant-General Piet Joubert took a thousand men from the Transvaal and crossed the border into Natal, establishing a position a few miles inside Natal near Laing’s Nek. It was a wise move, for the Nek was a perfect defensive position for the type of warfare at which the Boers excelled. Laing’s Nek lies at a point where the Natal border narrows, flanked on one side by the Orange Free State and the other by the Transvaal. To the west is a high, mountainous region, overlooked by the prominent peak of Majuba Hill, whose spur runs west to east before terminating in a ridge that curves to the south. Farther east is the valley of the Buffalo River, which blocks movement in that direction. The Newcastle road, the only highway leading into the Transvaal capable of handling heavy wagons, runs over the spur, and its approach is thus dominated by the defensible ground on three sides. Joubert positioned his laagers (wagon-enclosed camps) on the reverse slopes on either side of the road and waited for the British.

Upon learning of the disaster at Bronk- horstspruit, the British government was both stunned and dismayed. All the reports concerning the situation in South Africa had indicated that the Boers were an undisciplined mob that would not fight. In full realization that the troops on hand were insufficient to handle the drastically changed situation, reinforcements from England and India were immediately ordered to South Africa. As it would take some time before these troops arrived, and since it was unknown how long the isolated garrisons could hold out, something had to be done immediately.

Major General Sir George Pommery Colley, the High Commissioner for South East Africa and commander of all British troops in Natal and the Transvaal, began assembling a force to relieve the besieged British garrisons. By January 24, 1881, Colley had concentrated his own ad hoc force at Newcastle in Natal. Totaling some 1,462 men, the Natal Field Force was composed of about 1,112 infantry from the 58th, 60th Rifles (3rd Battalion), and 21st Regiments, 190 cavalry from a mounted squadron and the Natal Police, and 127 men of the Royal Navy from HMS Boadicea.

Colley Gets To Put His Money Where His Mouth Is

Along with a few Royal Engineers there were also about 80 Royal Artillery with six field guns (four 9-pounders and two 7-pounders), two Gatling guns, and three 24-pound rocket tubes, as well as Service and Hospital Corps’ units. Although Colley knew reinforcements were on the way and was convinced beyond any doubt of the superiority of the British soldier, he believed that this force was sufficient to deal with the Boers. While in India, Colley had maintained that “500 men with breech-loaders could ordinarily overcome any opposition” on the Northwest Frontier. Now, with almost three times that number, he would have a chance to prove the validity of that claim in the Transvaal.

Advancing toward the Transvaal, Colley’s force made camp at Mount Prospect, three miles from the frontier. Learning of Colley’s approach, Joubert called for reinforcements and began fortifying his position with trenches and schanzes, stone-built walls. By the time Colley’s men reached Mount Prospect, the Boers had assembled some 2,000 men at the Nek. On January 28 Colley launched a frontal assault against the Boer positions. The 440 men of the 58th Regiment were meant to advance against the eastern end of the Boer line, their right flank covered by the Mounted Squadron and the whole supported by artillery. Having pierced the line at this key juncture, the 58th would then turn left and sweep down the Boers’ left flank and center, driving them from their position. With the highly respected 58th Regiment leading the assault, Colley had no doubt of the success of the attack against these armed civilians.

Had he known more of the specifics at Bronkhorstspruit, Colley might have been more cautious, or at least have had more respect for the capabilities of these “armed civilians,” particularly when they were entrenched on high ground of their own choosing. On reviewing the casualties at Bronkhorstspruit, a doctor noted the high number of multiple wounds suffered by the British, stating that they had “on an average, five wounds per man.” This was clear proof of the excellent marksmanship of the Boers, as well as their adept use of fire and movement tactics. Both of these skills had been developed through years of conflict against some of the fiercest warriors in South Africa. These undisciplined farmers could fight, and fight well.

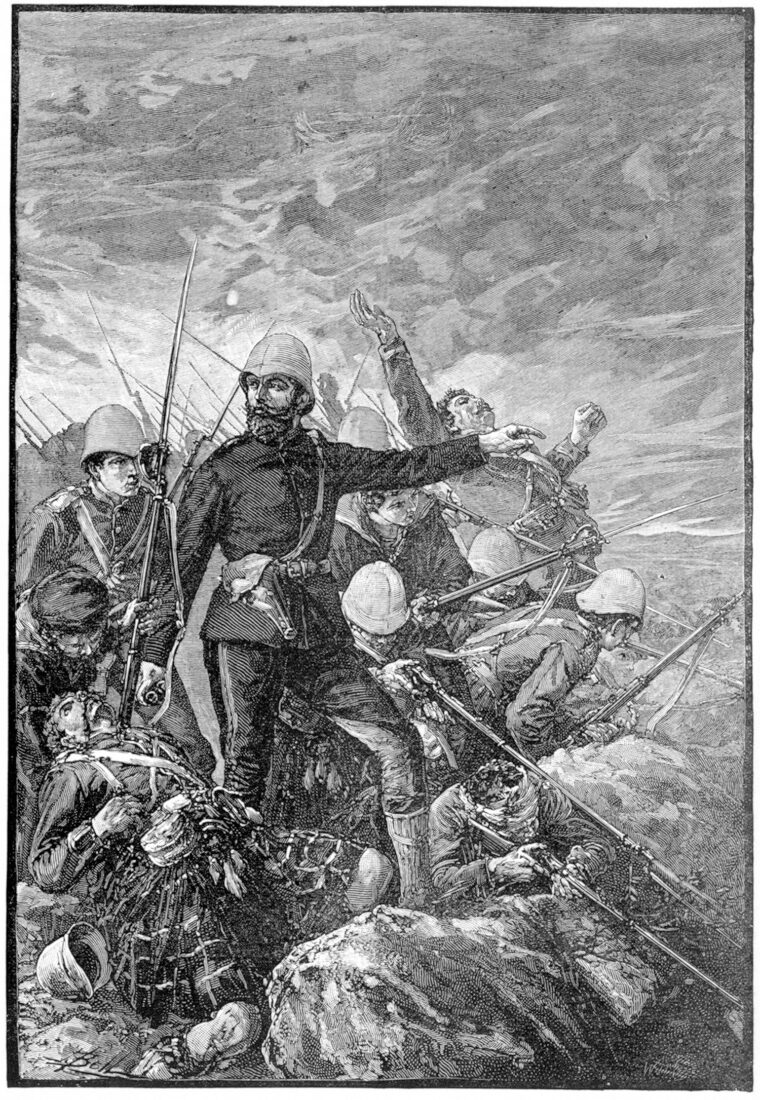

The attack went forward as planned, but the Mounted Squadron ordered to cover the 58th’s right flank impetuously charged up a steep hill against the Boer position. By the time they reached the top their horses were blown and they were easy targets. Their charge also left the 58th’s flank unprotected and so the Boer marksmen moved forward to pour fire into the infantry’s ranks. Despite the heroism of the 58th they were repulsed with heavy casualties. The 58th had gone into the attack with their regimental colors flying, but when the regiment was repulsed and one of the color bearers wounded, the colors had to be rescued. This was the last time a British regiment went into battle carrying its colors.

Colley withdrew his men and counted his losses: 84 officers and men killed, 113 wounded, and two captured. Boer losses were reportedly 14 killed and 27 wounded. Back in camp Colley took personal responsibility for the loss, stating, “We shall certainly take possession of that hill eventually, and I sincerely hope that all those men who have so nobly done their duty today will be with me then.” Colley then moved his camp back a short distance and strengthened its defenses. He hoped that the Boers would attack him, but he doubted they would. Attacking a fortified camp supported by artillery, of which the Boers were decidedly afraid, was not in their tactical manual. They had a different target in mind.

On January 25 the reinforcements from India began arriving along with Colley’s newly appointed second-in-command General Sir Evelyn Wood. By the end of the week, the British forces in South Africa had been augmented by the 2nd Battalion, 60th Rifles, the 83rd and 92nd Infantry Regiments, the 15th Hussars, an artillery battery, and a second naval brigade with two 9-pounders from HMS Boadicea and HMS Dido. Upon receiving word of the repulse at Laing’s Nek, these reinforcements began marching to join Colley’s force at Mount Prospect.

Meanwhile, the Boers had moved to interdict Colley’s supply and communication line along the Newcastle road. Learning that his supply wagons had halted owing to Boer activity, on February 8 Colley took a force of five companies of the 3rd Battalion, 60th Rifles, the remainder of the Mounted Squadron, and four guns—393 men total—to escort the wagons to camp. Confident that they would be back in time for dinner, Colley ordered that meal to be ready by 3:30 pm, and as such did not order either rations to be issued to the men or a water cart to accompany the column.

Casualties Mounted for the British as the Wounded Pleaded for Water

The column departed around 8:30 in the morning. Reaching the Ingogo River only a few miles from camp, the British crossed at a low ford and began moving toward the high ground of the Schuinshoogte plateau. Colley dropped off two 7-pounders and a company of the 3/60th to cover his river crossing, ordering a company of the 58th to leave camp and relieve this detail so it could rejoin the column. As the Mounted Squadron, which was scouting forward, approached the heights, rifle fire broke out. Colley quickly moved the column onto the triangle-shaped top of the heights and took cover among the rock outcroppings that studded the area. About a hundred Boers, under the command of Nicholas Smit, were seen forming along a low ridge on the British right. Colley directed the artillery to open fire, forcing the Boers to scatter and find cover. Instead of withdrawing, as Colley thought they would against artillery, the Boers began instead to advance on the British position using the tall grass and numerous boulders for cover. By noon the Boers had advanced to within about 150 yards of the British position and were singling out the artillery gunners and their horses. Casualties were mounting among the British, the wounded were crying for water, and the injured horses were running about the position, trampling any in their way. Colley reduced his perimeter, ordered infantry to help man the guns, and continued fighting. He also managed to get a messenger out to bring reinforcements from camp. The Boers were steadily reinforced throughout the day and tried to turn the exposed British left flank, but this move was countered. Smit then tried to cut off Colley’s escape route by positioning men near the river crossing, but this effort also failed as the reinforcing companies of the 58th arrived in time to drive off the Boers.

With darkness approaching and his force now augmented to about 500, Smit wanted to finish off the British before night fell, but his men would not advance any farther against such determined British resistance. By 5 pm the skies opened and rain began to pour onto the battlefield. Smit withdrew, believing that the British were trapped, and without horses would at least have to abandon their guns. They would finish Colley off in the morning.

Equally determined, Colley evacuated his position during the night. Using infantry to haul the guns, the remnants of his column quietly left their position and taking a roundabout route crossed the swelling Ingogo, reaching the safety of camp at about 4 o’clock the next morning. The Boers had pulled back to take cover from the rain, and the few sentinels left did not notice the British move. The next morning Smit was amazed to find in the former British position only those troops too badly wounded to travel. His quarry had escaped.

Colley had thus suffered two serious reverses at the hands of the Boers. His losses at the Ingogo had been heavy—64 killed, 77 wounded, as well as 37 of the 65 artillery and mounted squadron horses. The Natal Field Force had lost a quarter of its total strength and Colley felt his force too weak to even hold the camp. Further, Colley had lost almost all of his staff in the two actions, leaving only his brother-in-law, Lieutenant Bruce Hamilton, and Major Edmund Essex who, having survived both the 1879 Isandlwana and Laing’s Nek battles, had earned the moniker “Lucky Essex.” He again spoke to the men, apologizing for his leadership at the Ingogo and taking the blame for the defeat onto himself. Despondent over the loss to his command and his staff, Colley wrote to his sister, “Reinforcements are now arriving, and I hope it will not be long before I have force enough to terminate this hateful war.”

On February 23 the reinforcements of the “Indian Column” reached the camp at Mount Prospect. Colley was pleased to have such experienced Indian veterans with his command. Among these men were the 92nd Highlanders who, wrote Ian Castle in his 1996 work Majuba 1881, were “about to change the look of warfare in southern Africa. For the first time, an Imperial unit took the field wearing khaki tunics.” With his force now augmented by an additional 737 officers and men, Colley’s confidence and spirit were renewed.

There was one piece of bad news, however, in that the Boer Triumvirate had extended a peace proposal to resolve their dispute with Great Britain. If the British government annulled the annexation of the Transvaal they would agree to plead their case before a Royal Commission of Inquiry. After much debate, London decided on a conditional acceptance of the Boer proposal and instructed Colley to arrange an armistice until the commission could be formed. Colley’s reaction was one of anger and indignation. Now that he had the necessary men to end the war and redeem his previous defeats, the government had forbidden him to make any aggressive moves against the Boers.

Colley delivered the government’s response to the Boers on February 24 but, within the sphere of his authority, only allowed 48 hours for a reply. Nicholas Smit informed Colley that Piet Joubert was 200 miles away at that time and that it would take at least four days to get the message to him and return with a reply. Joubert received the British proposal around February 28 and agreed to the terms, but his response did not reach Laing’s Nek until March 7. By that time, Colley was well past caring.

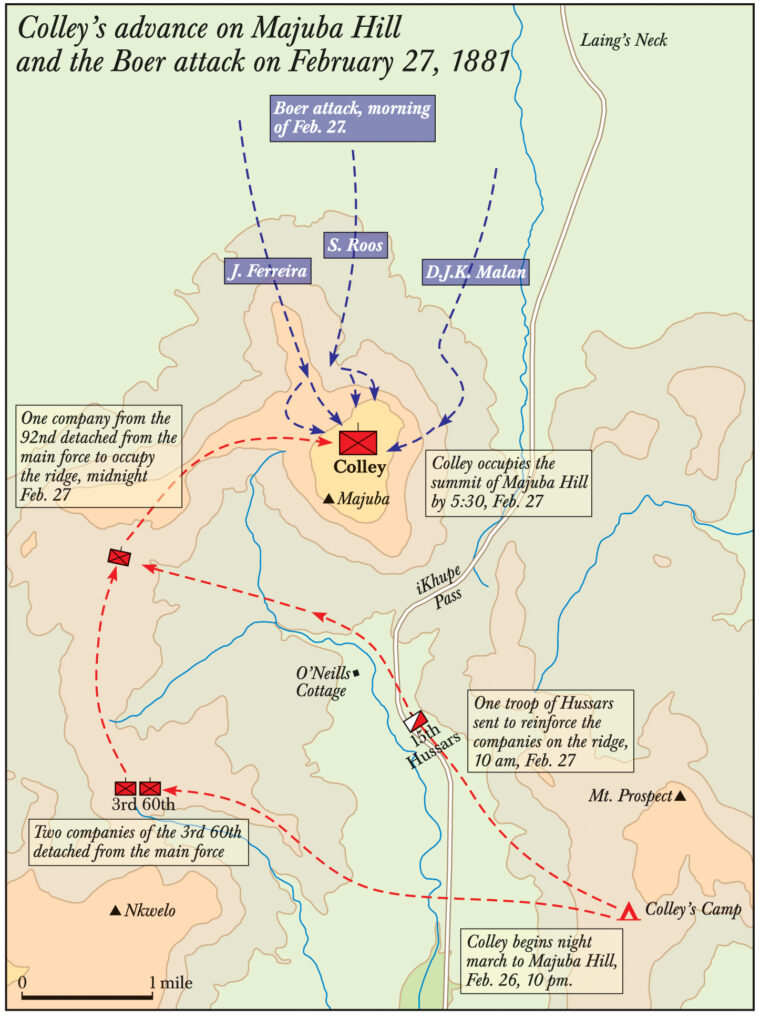

While waiting for the Boer response, Colley considered his next move. Although he could not take any directly aggressive action against the Boers, he could act defensively. Zulu scouts had informed Colley that the Boers removed their pickets from atop Majuba Hill every evening, thus leaving the position undefended. Colley therefore decided to move a detachment onto the top of Majuba Hill. As Majuba lay within Natal and not the Transvaal, such a move could not be considered aggressive, and to occupy Majuba meant that he would have a force overlooking the rear of the Boer position along the heights at Laing’s Nek. Occupying Majuba might prove just the maneuver needed to force the Boers to retreat, thus hopefully restoring his military reputation before the war was ended by the politicians.

Colley’s Bold and Secret Plan

On February 26, without informing his staff as to his intentions, Colley put his plan into action. At 9:30 that evening he issued orders to assemble a mixed force of about 595 men, composed of two companies each of the 58th and 3rd/60th Rifles, three companies of the 92nd Highlanders, a company from the naval brigades, and elements from the 2nd/21st Regiment and Medical, Hospital, and Service Corps. Each man of the force would carry 70 rounds of ammunition, three days’ rations, a full water bottle, greatcoat, and waterproof sheet. Each company would also bring four picks and six shovels. No artillery or Gatling guns would accompany the column.

Although the force was approximately of battalion strength, its mixed composition denied it the cohesion of a battalion organization. The dissimilarity of the component companies further aggravated any chance of unit integrity. This was especially the case with the Highlanders who, being an old regular regiment fresh from a victorious campaign in Afghanistan, looked upon the other units in the force, still smarting from two recent defeats, as poor soldiers. Why Colley chose to assemble such a conglomerate force from four different units instead of using the entire fresh battalion of the 92nd Regiment is unknown. It has been suggested that since he believed this maneuver would lead to certain victory he wanted all the elements of his force to participate. Perhaps he also wanted to give some of those who had just suffered two ignominious defeats a chance to “get their own back” from the Boers. Whatever the reason, this decision was to prove a grave error.

Having ordered no lights to be brought and complete silence to be maintained during the march, Colley’s force started out for the hill at around 10 pm. Despite being ignorant of their destination, many of the men were in good spirits and were even envied their adventure by those left behind. Not everyone in the column, however, was so enthusiastic. Captain Marling of the 60th Rifles stated, Colley “ought not to be trusted with a corporal’s guard.” Colonel Bond of the 58th received a report from one of his company commanders that “the men had lost confidence in Colley and had an idea they would be led into another trap.” Lieutenant Ian Hamilton of the 92nd overheard men from the 58th tell his Highlanders “they wished we had brought the whole Regiment.”

Having reached Nkwelo Hill, Colley turned northeast and moved the column along the ridge connecting Nkwelo with Majuba. Here, Colley detached two companies of the 60th Regiment as pickets, to safeguard his line of march and communications. These men were not told the destination of the column and were simply ordered to hold their position. Around midnight Colley dropped off a company from the 92nd with orders to dig entrenchments and await the arrival of a company from the 3rd/60th Rifles from camp. They would also mind the officers’ horses, which could proceed no farther up the hill.

“Looking down from our position right into the enemy’s lines, we seemed to hold them in the palm of our hands.”

With two miles to go to reach Majuba the column pushed on, the men struggling under the weight of 58 pounds of equipment and the ever steeper incline of the hill. “I remember it as if it were yesterday,” Lieutenant Hamilton wrote, “the tense excitement of that climb up with a half-dozen shadowy forms close by, which were swallowed up and disappeared if they got further away from me than half a dozen paces.” The last part of the climb was such that the men had to crawl up on their hands and knees, grabbing at tufts of grass for a handhold. At 3:40 Sunday morning, February 27, Colley and the head of the column reached the summit. By 5:30 the entire column was up and the sun was rising. Below them lay a panoramic view of the entire area, from the Boer positions at Laing’s Nek to their own camp at Mount Prospect. Thomas Carter, one of the correspondents who accompanied the column noted that, “Looking down from our position right into the enemy’s lines, we seemed to hold them in the palm of our hands.”

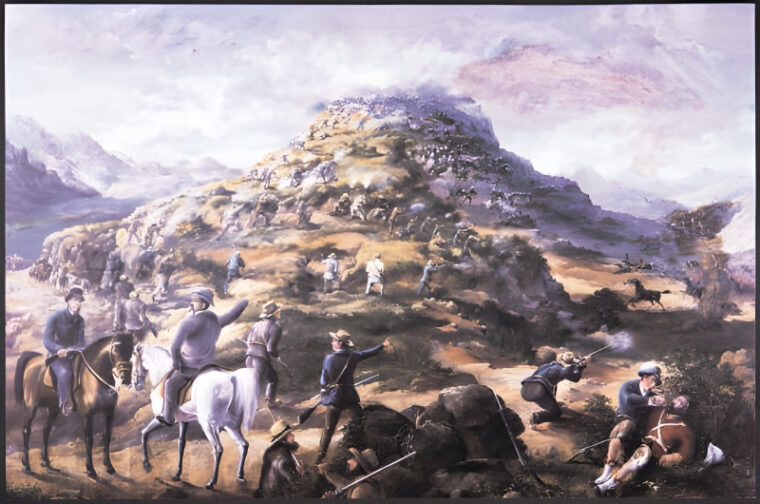

Majuba, from the Zulu word amajuba, meaning “hill of doves,” is an interesting piece of terrain. The top of the hill is a relatively flat plateau, shaped like an isosceles triangle, with the base or northeast side about 500 yards long, and the southwest and west sides roughly 425 yards long. The latter sides fall steeply down to a series of tree- and scrub-covered ravines, while the northeast side slopes more gently to a terrace about 100 yards wide, and then down again to another lower terrace. The ground is further accentuated by two knolls about 100 yards apart, which lie at the northwest and southwest angles of the perimeter. There is also a low rise, some 20 feet higher than the plateau that starts on the north end of the west face, runs toward the northeast face, and curves around the perimeter to rise slightly above the southeast angle, finally ending at the southwest angle and enclosing a hollow about 350 yards all around. In conversation with Lieutenant Colonel Stewart of his staff, Colley remarked, “We could stay here forever.”

Deducting the detachments left along the ridge, Colley had 405 officers and men left to occupy the hill. After detaching 120 men from all the companies to form a reserve, which he placed in the central hollow with the hospital, Colley then positioned the 58th between the southeast and southwest angles, the sailors on the west face and the southwest knoll, and the 92nd from the hillock around the southeast corner. What was left of the 92nd under Hamilton was spread thinly from the northeast all the way to the southeast corner, the soldiers up to 12 paces apart. This disposition was ordered without appropriate consideration for the relative difficulties on the various sides of the hill. Convinced that his sheer presence on the prominence would cause the Boers to withdraw, and claiming that the climb had so tired the men that they needed rest, Colley did not order them to entrench their positions.

The next morning the Boers were surprised to find an enemy force on Majuba Hill overlooking all their positions, including their rearward-most areas. Said Carter, “The Boer army had risen from sleep, and in every tent and wagon there was a light.… It was a thrilling sight from our point of vantage; there was our enemy at our mercy, and unaware of our proximity to them.”

The first person to notice their presence was Hendrina Joubert, the wife of Commandant-General Joubert. She had woken early and gone out to put a kettle on the fire. She was startled to see Colley’s men on the hill and several of the Highlanders shaking their fists and calling out to the Boers to “Come up here, you beggars!” She quickly woke her husband saying, “Piet, come here. There are people on the kop.”

Realizing the Stakes, Joubert Calls for a Council of War

Panic spread through the Boer lines when they realized they had been outflanked, and that at any minute artillery shells could come raining down on them. They quickly started to break camp, but after a while when nothing happened the Boers rallied. Several of the more experienced men responded immediately. They quickly rode forward and dismounted at the base of the hill, taking advantage of the cover provided by the trees and ravines. Seeing the Boers, a lieutenant of the 58th took a rifle from one of the men and tried a shot. Although well out of range, his shot prompted a response from the Boers, who now returned the fire. Colley, hearing British rifle shots and having no desire to provoke the Boers, ordered the firing stopped.

Joubert, realizing that “everything was lost to us … if they retained possession of the hill,” called a council of war. It was determined to fight and try to regain the hill. While Joubert rode to prepare the defenses at Laing’s Nek for an expected attack, Smit called for volunteers to attack the hill. About 80 men quickly rode off toward the prominence while Smit organized another group of about 150 and sent them riding around the hill to the west to cut off Colley’s avenue of retreat. While some Boers kept up a long-range fire against the British positions, others under Commandant Ferreira and Field-Coronet Roos split into two groups and began moving up the northeast face. By 6 am there were several groups of Boers assaulting the hill and they were being reinforced by more men from Laing’s Nek when the latter realized that there would be no British attack against them.

As more Boers came into action, Joubert committed some of them to support Ferreira and Roos’s attack on the northeast and others to assault the west face of the hill. By around 7 am some 300 Boers were engaged, about half assaulting the hill, the remainder providing covering fire from below. Although the Boers’ fire kept his men pinned in place with their heads down, there was little other effect, and Colley seemed content to do nothing more than send a message to his camp at Mount Prospect by heliograph at 8 o’clock to be forwarded to the Secretary of State for War: “Occupied Majuba mountain last night. Immediately overlooking Boer position. Boers firing at us from below.”

An hour later he signaled again, ordering reinforcements from Newcastle to Mount Prospect and insisting they arrive by the following morning, but giving no orders or instructions for them when they arrived. Walking around in tennis shoes with his pant legs tucked into his socks, Colley moved among the men, talking with them and seeming completely relaxed. Thought Castle, there was “no sign of excitement or trepidation about him. Everything he did was in his usual deliberate, quiet, cool manner.”

By now, the Boer fire was increasing and things were, as one officer put it, “warming up.” When Lieutenant Hamilton reported to Colley the buildup of the Boer forces that were ascending the hill, Colley thanked him and sent him away. As the first British casualty came into the hospital at around 9:30, Colley signaled the camp again: “All very comfortable. Boers wasting ammunition. One man wounded in foot.” Colley continued to traverse about the camp, chatting with his staff and discussing where the men might build some redoubts. Suddenly his friend, Commander Romilly, Royal Navy, was mortally wounded while walking at his side. Colley was greatly distraught by this and his mood changed significantly. He was now reported to be “gloomy and silent” with a “grave and reserved expression.” At around 11 o’clock he signaled the camp again, this time giving an erroneous report of the Boer situation: “Boers still firing heavily on hill, but have broken up laager and begin to move away. I regret to say Commander Romilly dangerously wounded; other casualties three men slightly wounded.”

Lieutenant Hamilton reported to Colley twice more, stating that the Boer numbers had risen to 200 then to 350, and were continuing to increase. Colley again thanked and dismissed him. Concerned, Hamilton asked for reinforcements and received an officer and five men of the 58th. Around noon, Carter sent off a telegram to his newspaper: “Firing kept up incessantly by Boers—our men very steady, return fire only when good chance offers … Boers cannot take position from us … they are keeping up average of sixty shots per minute … the Boers have inspanned [harnessed] their cattle and are evidently ready to trek at a moment’s notice.” What Carter did not know was that the British weren’t returning much fire because they had no “good chance” due to the Boers’ skillful use of the dead ground fronting parts of the British position.

Shortly after noon Hamilton returned again to report that Boer strength had risen to about 450 men, only to find Colley asleep and Colonel Stewart reluctant to wake him. Hamilton, now very concerned, returned to his position. At around 12:45 the interior of the British position heard what sounded distinctly like massed volley fire. Colley immediately awoke and asked about the situation. He would soon see for himself.

Colley “Seemed to Have Lost His Head”

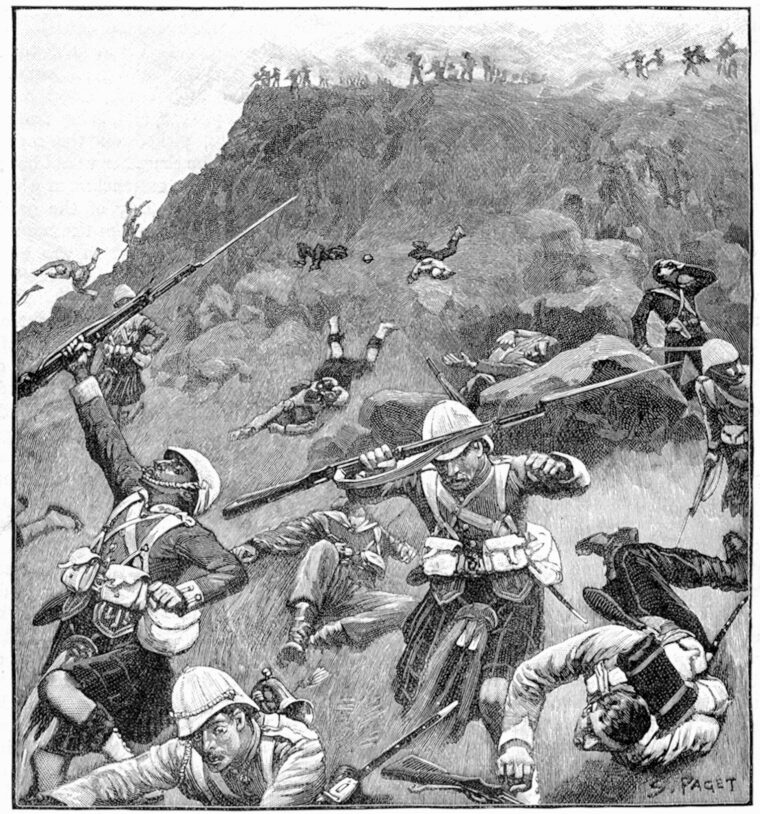

The commandos of Ferreira and Roos, by using the natural cover provided by the terrain and their own fire-and-movement tactics, had managed to approach close to the Highlanders’ positions on the northeast face. Suddenly, Ferreira’s men stood and delivered a volley at close range while Roos’s men charged the Highlanders in the flank. The bulk of the Highlanders were killed immediately and Ferreira occupied the knoll, sending the remnants of the Highlanders fleeing for safety while at the same time providing covering fire, which enabled Roos’s men to reach the northeast rim. The surviving Highlanders called for the reserves who, having just been roused themselves, were slow to respond and had to be urged forward amid the growing confusion. As the reserves charged over the hill they collided with the fleeing Highlanders. A panic suddenly gripped the British force as reserves and Highlanders alike retreated to the cover of the low rise above the hollow near the center of the British position.

With the northern part of the plateau carried, Ferreira and Roos’s men opened a deadly fire against the low rise from 100 yards or less. Lieutenant Hector MacDonald of the 92nd, who had been stationed on the western hillock with 15 men, was reinforced by some of the 58th and managed to lay in a flanking fire across the front of the rise. He was soon brought under fire from Boers who had ascended the western face, and began to suffer heavy casualties. The British troops behind the rise were then ordered to fix bayonets, but Colley refused to give the order to charge. Captain Morris of the 58th later reported that Colley “seemed to have lost his head, to be overwhelmed by the appearance of affairs.”

Slowly men began to abandon their positions at the northeast face—at the right rear of the rise—and join their comrades behind the rise. This movement began to weaken the northeast position just as the Boers were moving more men to that very spot. Hamilton, aware of the critical position the British were now in, implored Colley to order the charge, stating, “I do hope, General, that you will let us have a charge, and that you will not think it presumption on my part to have come up and asked you.”

“No presumption, Mr. Hamilton,” Colley replied, “but we will wait until the Boers advance upon us, then give them a volley and charge.”

Roos, sensing that the time was ripe, jumped up, waved his hat, and shouted, “Come on you chaps! The English are flying!” Roos’s men followed him at the run, while at the same instant Ferreira’s men came forward on the right rear of the rise, linking up with Roos’s right flank. That was all it took. Carter reported a “sudden piercing cry of terror” and then the British right crumbled beneath the onrush of the exultant Boers. Wrote Michael Barthorp in his 1987 Anglo-Boer Wars: The British and the Afrikaners, 1815-1902: “Panic spread rapidly and the whole line behind the rise gave way, the men racing for the south-west corner to get away from the Boers’ devastating fire. All over the plateau the broken troops raced for safety, most making for the track, some leaping over the precipices, as the Boers ran forward to shoot them down.”

Hamilton, his wrist shattered by a bullet, fell to the ground. As he looked over his shoulder he saw Colley, revolver in hand, waving to the men and trying to get them to hold the ridge on the southwestern face of the mountain, which lay across their line of retreat. A moment later, Colley fell dead, shot through the head.

The only British resistance was now from the western hillock where MacDonald and his little band of the 92nd and 58th kept up a heroic defense. With half their number killed and wounded, the rest of the British force disappearing over the rise, MacDonald told the few survivors to flee as best they could. Except for himself and a Sergeant Giles of the 58th, every man of MacDonald’s command had been hit. Giles and MacDonald were captured but not before MacDonald laid into the Boers with kicks and blows. His life was spared by the pleas of one of the Boers who, according to Carter, declared that “such a brave man should not be shot.”

239 British Casualties, almost 60% of the Entire Force

The Boers’ blood was up to such a height that not even the hospital was spared, and if not for the intervention of older, cooler Boer heads, even the British wounded and prisoners might have fallen victim to the slaughter.

In a little more than half an hour it was all over, the Boers gaining a complete victory. At the cost of an amazing loss of only one killed and six wounded, the Boers had virtually destroyed Colley’s force and sent the shattered remnants fleeing down the hill for their lives. Out of the 405 British troops on the hill, 85 were killed, including Colley; 119 wounded; and 35 captured; totaling 239 casualties, or 59 percent of the entire force.

The low number of Boer losses proved, according to Barthorp, an undeniable “tribute to their amazing skill at fieldcraft and fire and movement, a practice then unknown in the British Army.” In all fairness to the bravery and skill of the Boers, however, their victory was in large part made possible by Colley’s errors. Had he entrenched the British position, or reacted earlier to the mounting numbers and firepower being brought against him, or acceded to requests for a bayonet charge to dislodge the Boers from their positions, the affair might have had a different ending. The results of Majuba Hill, therefore, were due as much to Colley’s underestimation of the Boer’s fighting ability as to that ability itself, with the consequence that the “hill of doves” would forever after be linked with humiliating defeat in the annals of British military history.

Following Majuba, the First Anglo-Boer War came to an end, the two governments reaching an agreement that gave a temporary independence to the Transvaal. The British government had determined that the Transvaal simply wasn’t worth any further bloodshed. But many in the British Army were incensed that a peace had been declared before the stain of Majuba could be wiped away.

For the Boers, Majuba Day became a cause for yearly celebrations and an important symbol in their history. Years later, Hamilton, by then Lt. Gen. Sir Ian Hamilton, whose arm had been permanently crippled from his wound, remarked that “Majuba was worth an arm any day.”

It would not be until 19 years later, during the Second Anglo-Boer War, that the shame of Majuba would be erased. On February 27, 1900, British General Lord Roberts forced the surrender of a 4,000-man Boer army at Paardeberg. The Boer commander, General Piet Cronje, remarked to Lord Roberts during the surrender, “You have taken our Majuba Day away from us.” Roberts had made the final attack on the anniversary of Majuba at the urging of a survivor of that battle and the last British soldier left fighting on the field—then a lieutenant, but in 1900, General Hector MacDonald.

Please could you tell me if there is any record of the names of the boer casualties and dead from the battle of Majuba. I am researching my family history and one of my husbands kin left a notation regarding Barend Van Der Merwe born 1850+- died Majuba, Natal 1882 and the story goes, from injuries received from that battle.

Thank you for any input regarding this,

Sharon Wood