By Allyn Vannoy

The U.S. Army’s drive across France and Belgium during the late summer and fall of 1944 was made possible by the support of the logistics and maintenance personnel that performed their duties magnificently—but received little credit or glory. But those “up front” could not have accomplished their job without these hard-working and dedicated units. In many cases, their work was not only difficult but dangerous.

One of those support personnel was First Lieutenant Belton Y. Cooper, who went on active duty with the U.S. Army in June 1941 and was subsequently assigned as an ordnance officer. He attended the Army’s Ground Force School at Ft. Knox, Kentucky, where he received instruction on tank and vehicle maintenance, as well as tactics in armored combat.

This instruction proved valuable later during his service in Europe and also provided an appreciation of how German armored superiority forced American tank commanders to disregard doctrine and improvise in the face of tactical situations. Cooper would be assigned to the 3rd Armored Division’s Combat Command B (CCB), the equivalent of an infantry regiment.

Of the 16 armored divisions of the U.S. Army in World War II, only the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions maintained their armored heavy organization—having two armored regiments and a single armored infantry regiment, whereas the light armored division had just three tank battalions and three armored infantry battalions. The heavy armored divisions had 232 medium tanks as compared to 168 medium tanks for the light armored divisions.

Although inferior in firepower and armor to heavier German models, the division had as many tanks as two-and-a-half German panzer divisions. The 3rd Armored Division included the 32nd and 33rd Armored Regiments and 36th Armored Infantry Regiment.

Following each of the unit’s combat operations, maintenance personnel would go forward to locate damaged vehicles. Per operating instructions, unless they were able to locate the knocked-out tank and obtain its vehicle number, along with determining the extent of the damage, it was difficult to obtain a replacement tank through supply channels.

Once the extent of damage to a vehicle had been determined, a decision was made as to whether it could be repaired by the combat maintenance facilities, or whether it would have to be left for the army ordnance depot to pick up later. In the latter case, a request would be made for a replacement vehicle. If the tank was in a minefield, the engineers would be called to clear a path so that recovery vehicles could get to it.

Maintenance personnel sometimes found themselves close to the action—sometimes too close.

The 3rd Armored Division landed in France on June 24, 1944, and was sent to the St. Lô area as U.S. forces fought to break out of the Normandy bridgehead.

As the division moved forward, Lieutenant Cooper found himself at the head of the liaison group just behind CCB’s headquarters. Just east of the town of Airel, north of St. Lô, they came upon a burning building along the roadway where two dead American soldiers lay naked on the ground near a jeep. They appeared to have attempted to take cover from artillery fire when a shell struck the building and the blast deflected down upon them. It had blown them out of the jeep. They were terribly burned. Cooper and his driver were revolted at the sight—the war was now very real to them.

As Cooper’s column continued on, moving through defilade between hedgerows, they came under fire. They found themselves with Germans in the hedgerows to their north and Americans in hedgerows to their south. Fortunately, the hedgerows were high, and most of the bullets and shells passed over their heads. The column crawled slowly forward in the dark without blackout lights.

At the top of a hill, they were directed into a field that was the CCB headquarters’ bivouac. But the area was also on the forward slope of the hill and open to direct enemy fire. They later learned that the Germans had hoisted a 75mm PAK-41 anti-tank gun into a church steeple about a quarter-mile away. Luckily, the darkness had hidden the CCB headquarters. Close to daybreak, one of the American tanks was able to locate the anti-tank gun and knock it out.

The CCB’s first Vehicle Collecting Point (VCP) was established near Airel with the 33rd Maintenance recovery crews starting to bring in damaged vehicles. As tanks and other armored vehicles arrived at the VCP, the horrors of the war became apparent. Maintenance crews had to crawl inside and clean up the remains of crewmen—blood, gore, and brains were splattered everywhere. Body parts and soldiers’ identifications, if any, were gathered and turned over to Graves Registration personnel.

Strong detergents and disinfectants were used to clean the interior before repair crews began their work. After repairs were completed, the interior was repainted. Despite this, the stench of blood and death could not be removed.

As the Allies advanced across France and Belgium the combat elements would set up in a circle off the road before nightfall, forming an all-around defensive position. Tanks and infantry would establish an outer perimeter, and the maintenance, medical and supply units would be on the interior, where they could do their work. At daybreak, when the combat units moved out, the maintenance unit commander designated repaired vehicles that were considered ready for action and returned to their units or were towed to the next stopping point.

If there were more damaged vehicles than the wreckers could accommodate, a VCP was established and the ordnance company commander detached a maintenance platoon to remain at the VCP and repair the vehicles still needing work. This work could take several days—the platoon often being in areas where enemy units were still active—requiring the maintenance personnel to be responsible for their own security.

After the vehicles were repaired, they were returned to their units, and the maintenance platoon moved forward to rejoin the ordnance company. In some instances, there would be several VCPs along the route of advance. This system of repair, along with replacement vehicles brought up each day by the ordnance liaison officer, allowed the combat command to continue to advance and fight as an effective force.

Towards the end of the day, a list was prepared of all the vehicles and other ordnance work in the VCP. This included any spare parts needed, along with a list of all vehicles considered too badly damaged and that had been cannibalized for usable replacement parts. There was also a list from the recovery crews of any tanks and other vehicles that had been damaged beyond repair and had not been recovered. From these lists Lieutenant Cooper created a combat loss report after each action of CCB.

After dark each day, Cooper was responsible for delivering the combat loss reports to the division maintenance battalion headquarters some 30 to 50 miles behind the front. Because of the sensitive nature of the information, it could not be sent by radio, but had to be hand carried. The reports were placed in a wooden box in the back of Cooper’s jeep along with a thermite grenade. In the event of an ambush, the grenade was to be set off and the reports destroyed.

During the division’s advance, the armored combat commands would bypass many enemy positions—leaving them for trailing infantry to mop up a day or more later. So, the trip to deliver the reports presented possible hazards.

Cooper and his driver would leave the combat command VCP after midnight, driving without blackout lights. The jeep’s windshield was lowered and covered with canvas, and a small angle iron wire-cutter was mounted on the bumper to protect against wires that the Germans sometimes stretched across a roadway to decapitate those riding in jeeps or on motorcycles.

Cooper and his driver lived in their jeep. The inventory of the items that Cooper carried onboard the jeep included two bedrolls, two backpacks, two ponchos, a pair of binoculars, a case of 10-in-1 rations, a case of K-rations, and the wooden box for reports with the thermite grenade inside. Cooper carried a .45-caliber automatic pistol and his driver had a .30-caliber carbine. In addition, they had a 1903 Springfield rifle, two .30-caliber M1 rifles, a box of hand grenades, and two German panzerfausts they had found.

When Cooper arrived at the division maintenance battalion headquarters, he would report to the maintenance battalion shop officer and provide him the combat-loss report. He also would give him information on the tactical situation as well as the location of knocked-out tanks and other vehicles. Cooper would then lead fresh vehicles forward daily, when needed, enabling the combat command to maintain its strength.

Cooper was required to maintain knowledge of the location of the division maintenance battalion headquarters and the relative location of combat units. Leading the column of replacement vehicles also required some idea of where the combat command was headed. This information was critical to operations, but also made Cooper a valuable asset as well as a concern if he should be captured.

When Cooper and his driver paused to catch some sleep, they would dig a two-man foxhole about seven-by-five-feet long and two feet deep. They would cut down small saplings and place them over the hole, then place their shelter halves on top. A layer of dirt several inches thick was placed on top of this with a small entrance left at one end.

While this would not withstand a direct hit by artillery shells, it offered some protection from near hits; as long as they were able to stay below an explosion’s blast cone, they had a chance of surviving. The overhead cover was also important as German night bombers would scatter butterfly bombs—small bomblets about the size of a hand grenade—over an area.

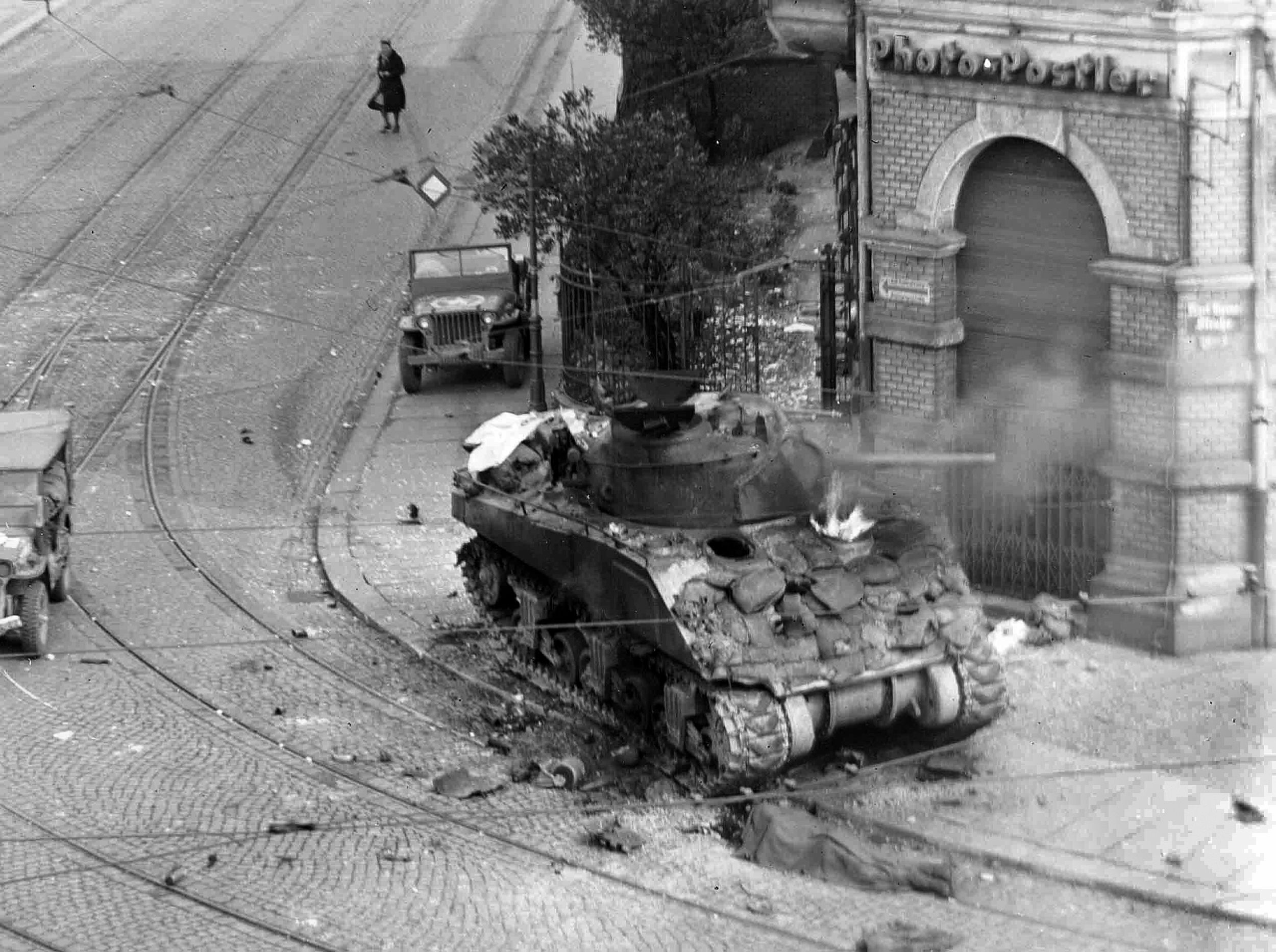

After fighting near Airel, France, a VCP was established and a steady stream of knocked-out tanks and other vehicles were delivered to the VCP.

As armored vehicle casualties mounted, new procedures needed to be adopted. Ordnance logistics training for operations on the continent had been based on the assumption that vehicle casualties, especially tanks, would be much lower than they were in reality, so supply of spare parts was grossly inadequate. The directive had been to not cannibalize tanks.

Cooper’s commanding officer, Major A.C. Arrington, was shocked when he saw the first combat-loss report—that the M4 Shermans were suffering terrible losses. He ordered that every seriously damaged vehicle be cannibalized so that other tanks in the VCP could get back in operation quickly. Also, replacement vehicles and tanks were now requested orally, rather than waiting for paperwork to be processed.

Maintenance crews erected shelter halves over the back end of tanks so they could work on engines in the field after dark. They were extremely careful working under tarps after dark as the slightest glimmer of light could be seen for miles by low-flying aircraft. Working around the clock, crews caught catnaps whenever they could.

The 3rd Armored Division had entered combat in France on June 29; by July 16, the division had only penetrated five miles into enemy lines, but had lost 87 M4 Shermans. This figure did not include those that had been repaired and returned to units.

Among the problems with the M4 Sherman was its engine. The tank’s air-cooled radial engine had been selected as a result of the lack of funding during the pre-war years, prompting the use of surplus aircraft radial engines. The use of such engines in tanks resulted in greater fouling of spark plugs—with nine cylinders, and two plugs per cylinder—maintenance was not an easy undertaking. The units made an effort to replace these with Ford V-8 engines whenever possible as they were easier to maintain.

If a projectile penetrated to the interior of the tank, a series of incandescent particles would shower the crew compartment, killing or seriously wounding the crew. The incandescent particles would also generate small splinters which, if embedded in the electric cables, would short out systems.

Often, the sparks would set the tank on fire. Repairs were made quickly to the least damaged tanks. If a tank had not been burned out completely, it could usually be repaired. Hits to the gas tanks or engine would also result in fires. Heat from a fire would anneal the hardness of the armor plate so that it was considered beyond repair.

Ordnance maintenance crews were also responsible for familiarizing replacement crews with replacement tanks, particularly if they had new equipment. This grew more vital as the number of veteran tankers declined. The ability of the division to restore its strength after heavy fighting depended largely on the capability of maintenance crews to train new personnel and get the tanks and crews ready to return to operations.

Cooper’s duties required him to travel day and night, taking note of potential trouble spots. Near the crest of a hill just outside the town of Maubeuge, France, near the French-Belgium border, a column of repaired tanks led by Cooper paused as he went forward to reconnoiter. On the lower slope of the hill before him was a large wooded area to the left of the roadway, and an open field to the right with woods about 300 yards beyond.

Approached by a French farmer, Cooper learned that German soldiers occupied the woods to the left of the road. He also learned that there was a French Resistance headquarters in Maubeuge where he could obtain more information on the local situation. After informing his sergeant of the situation, he headed off to Maubeuge.

Cooper found the Resistance headquarters guarded by civilians armed with a mix of German and American weapons. He was led to a situation room, the walls covered with maps showing the positions of both enemy and friendly forces. The French commander was a tall, good-looking blonde woman, dressed in GI coveralls. She had excellent command of the situation that she shared with Cooper. He learned that the 3rd Armored Division was at Mons, Belgium, just to the north, under pressure from the Germans.

Returning to his column, Cooper prepared his crews to move out. While no enemy movement had been seen in the suspect woods, the tank commanders were directed to swing their guns to the left as they moved down the road. Their objective was to get the tanks to the division and not to be delayed by a firefight.

As they prepared to move out, the assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry Division, Brig. Gen. Willard Wyman, leading the 26th Regimental Combat Team, appeared on the scene, asking who was in charge of the column of tanks. Wyman was surprised to learn that a first lieutenant was leading what he thought was a task force.

Wyman asked if Cooper thought he could use his column as an effective fighting force. Cooper explained that his tanks did not have radio communications with one another, but that they could use hand signals and could put up a good fight if they had to.

Wyman directed Cooper to set up a perimeter and await further orders. Wyman then had his air liaison officer call for an air strike on the suspect woods. In a short time, six P-47 fighter-bombers appeared and circled overhead. They strafed and bombed the area, leaving the woods boiling with flames and secondary explosions. The next day, Cooper’s column reached Mons.

On September 15, as CCB was penetrating the Siegfried Line about a mile south of Kornelimünster, Germany, Cooper saw a long white plume of a rocket going straight up from the woods to his east. Unlike an artillery rocket, this one kept going straight up, not arching over. As he watched the rocket continue skyward, a second appeared, launched from near the first, following the same trajectory. The launch site appeared to be only about a mile to the east. The next day there was a report that the Germans had fired the first V2 rockets on Antwerp.

By September 23, the division had reached the Stolberg-Aachen area. Of the 400 tanks that the division had started with in Normandy, only about 100 were still operational. Although ordnance had replaced most of the losses, maintenance crews had undertaken extraordinary efforts as well to keep the combat units up to strength.

During September and October, as the First U.S. Army prepared to drive to the Roer River, attacks into the Hürtgen Forest had been extremely costly. The decision was made to use the 3rd Armored Division in a formal assault—contrary to doctrine.

A key terrain feature in the area of the assault was Hill 287, near Mausbach, east of Stolberg. The fall rains had turned the area into soggy terrain. In addition, the Germans had heavily mined fields in the area. But instead of planting their mines in front of the forward infantry positions as they usually did, they placed them slightly behind their forward infantry outposts.

Standard operating procedure was for combat engineers to infiltrate the outposts at night to locate and remove the mines, but this new arrangement negated such action. The Germans planned to hold their outposts as long as possible, leaving the Americans to deal with intact minefields.

The 3rd Armored Division was to penetrate the minefields on the reverse slope of Hill 287 and seize three heavily fortified villages in the valley beyond. CCB was to make the initial penetration.

The morning of November 16 was overcast with patchy ground fog. The attack began at 11:15 a.m. with a major bombing strike—hundreds of heavy and medium bombers struck the towns of Eschweiler and Langerwehe and targets further east. In addition, 90 field artillery battalions fired concentrations.

CCB assembled just southwest of Hill 287. As the CCB task forces proceeded over the crest of the hill, passing through American lines, they moved into the German minefields.

Each task force had one flail tank—a tank equipped with a series of heavy chains attached to a horizontal, rapidly rotating drum mounted on two arms in front of the vehicle—intended to clear minefields.

The tanks had to deal not only with the mines, but also with the extremely soggy ground. The flail tanks detonated several mines, but soon bogged down in the muddy fields. They were then knocked out by enemy gunfire.

The second tank in each column had to go around the flail tank in order to continue the attack. After proceeding several yards, it struck a mine and was disabled. The next tank bypassed this tank and, in turn, was disabled by a mine. This process continued with several more tanks encountering mines until one was finally able to make it through the minefield.

Hoping to take advantage of this success, the next tank attempted to follow the same path and made it through; however, as the third tank tried to follow the same path, it became mired in the soft ground. At the same time, the Germans continued to fire on the tanks until they set them on fire.

The assault had begun with 64 M4 tanks, but within 26 minutes 48 Shermans were put out of action. By nightfall, one of the task forces had only four operational tanks out of the 19 with which it had started the operation.

By the next morning, the engineers had cleared some of the mines on Hill 287, placing tape markers so that the recovery crews might reach the disabled tanks. Although most fighting had ceased in the area, there was still sporadic small-arms and mortar fire. When this happened, the recovery crews took cover until the firing ceased, slowing their efforts as they worked to remove the tanks.

In addition to the sporadic fire, there was still the danger of mines. In an effort to minimize the danger, the recovery crews attached 100-foot-long cables between the tanks and the recovery vehicles and attempted to winch the tanks from the field. The crews were able to recover all but eight of the tanks—those all having been burned out. Of those recovered, the maintenance crews were able to repair all but 13 in just three days.

By mid-December, the 3rd Armored Division and its attached units had a strength of approximately 1,800 combat vehicles and 2,300 wheeled vehicles, presenting a challenge of a diverse assortment of vehicles to the maintenance crews. In addition to the maintenance battalion, which had more than 1,000 men, there were another 1,000 men in the maintenance companies in the armored regiments, plus the platoons and maintenance sections of other units—a total of 2,000 involved in maintenance. There were also 8,200 drivers and assistant drivers who performed first-echelon maintenance on their own vehicles.

This seemingly large maintenance organization allowed the combat commands of the 3rd Armored Division to exploit breakthroughs and maintain the unit’s momentum.

Equipment was not only exposed to combat, as well as weather and poor road conditions, but the wheeled vehicles—850 two-and-a-half ton trucks in the division—were heavily overloaded. These trucks were often carrying as much as 10 tons.

On December 16, with the opening of the German Ardennes offensive, also known as the “Battle of the Bulge,” the 3rd Armored Division was ordered to Eupen, Belgium, north of the German advance. CCB left Mausbach, Germany, late on the afternoon of December 19, heading south, moving all night, through falling snow and freezing rain.

Maintenance personnel dealt with breakdowns while on the move in an effort to keep the columns on schedule. A column of 1,200 vehicles, half of them tanks, half-tracks, and other fighting vehicles, normally experienced 150 to 200 breakdowns during a march of 50-60 miles.

After the front was stabilized, as the Allies prepared to push back German forces in the Ardennes, maintenance personnel worked feverishly to ready equipment and vehicles for the coming fight. Maintenance efforts were complicated by the bitter cold. But the maintenance personnel felt lucky as compared to their infantry and tanker counterparts.

The constant exposure to the winter elements eventually caught up with Lieutenant Cooper. One evening, as he prepared to turn in for the night, he noticed that his feet seemed unusually sore, and then found large black splotches on the ball and heel of both feet. An examination the next day by the battalion surgeon determined that the spots were frostbite.

Cooper pleaded with the doctor not to send him to the hospital, afraid that the temporary transfer from the division might prevent him from returning. The doctor used a scalpel to peel away some of the skin, applied antiseptic, and bandaged his feet. Cooper remained at the aid station for a couple of days.

Heavy losses during the Battle of the Bulge resulted in a critical shortage of tank crews. The standard M4 Sherman had a crew of five, including driver, assistant driver, gunner, assistant gunner (or loader), and the tank commander. The first to go was the assistant driver, eliminating the use of the hull’s ball-mounted machine gun. Next, the assistant gunner was removed, the tank commander having to double as the loader.

On January 8, 1945, as 17 tanks were prepared to be issued to combat units, the ordnance unit had to not only ready the tanks, but to also find crews to man them. The 33rd Armored Regiment sent them 17 tank drivers who had limited or no combat experience. Another 35 soldiers came from the replacement pool, but had no experience or training with tanks. Thirty-four of these men were selected and split into two-man teams.

They, along with the drivers, made up 17 three-man crews. They were given a brief orientation covering the equipment and vehicle operation—shown how to operate the turret, load the main gun, and given a chance to fire three rounds.

Cooper later learned that within less than a day, 15 of the tanks had been knocked out and destroyed. But he was unable to find out how many of the young crewmen were lost.

On January 20, the division moved to the Barvaux-Durbuy, Belgium, area for rest and rehabilitation. While there, the maintenance and supply units worked feverishly to get the division back up to strength.

During the fighting in the Ardennes from December 16 to January 20, the division had lost 125 M4 medium tanks, 38 M5 light tanks, six M7 self-propelled guns, and 158 half-tracks, armored cars, and other vehicles.

As an answer to the German heavy tanks, the first 20 M26 Pershing heavy tanks to arrive in the ETO were divided with 10 each to the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions. Five were issued to each armored regiment.

When the U.S. Army was developing the Pershing tank, a heavier vehicle with a wider track than the M4 and armed with a long-barreled 90mm gun, it was given a low priority for production. The Sherman was thought to be sufficient to meet the German tanks that would be faced.

The Pershing was the first completely new American main battle tank of the war—a radically new design. It weighed 47.5 tons as compared to the M4’s 34 tons. Although heavier than the Sherman, its longer and wider track gave it a ground-bearing pressure of three to four pounds per square inch against the Sherman’s seven pounds per square inch—indicating its better ability to cross muddy terrain. It had four inches of cast-steel armor on the glacis plate at 45 degrees, where the German Panther had three-and-a-half inches at 38 degrees.

The tank was equipped with power traverse and had a gyro-stabilized gun control, enabling it to fire while on the move—the gun remaining fairly level. The 90mm gun fired a heavy projectile at a velocity of about 2,750 feet per second. The Pershing’s 550-horsepower Ford in-line engine gave it a higher horsepower-per-ton ratio than the German Panther.

But the Pershings came too few and too late to have any significant impact on the fighting.

As the next phase of operations began, the 104th and 8th Infantry Divisions established a bridgehead over the Roer, followed by columns of the 3rd Armored Division crossing into the bridgehead on the night of February 24-25.

The concentration of an armored assault force in a small bridgehead presented dangers. As maintenance elements were moving into the bridgehead, Cooper witnessed anti-aircraft fire erupt, tracers arching skyward, seeming to focus on a part of the sky where a low-flying twin-engine German fighter appeared.

Cooper recalled that when he was stationed in Gloucester in May 1944, he had seen and heard the British Gloucester jet fighters being tested. He recognized the same shrill noise now—it was an Me262 that came screaming in low over their heads. In the next moment, an American P-47 Thunderbolt fighter was seen approaching in a sharp dive from several thousand feet, attempting to intercept the German jet. But the Me262 took off and easily out-distanced the P-47. Despite the impression it left on those who witnessed it, they knew that the momentum of winning the war was on their side.

The 3rd Armored Division broke out of the bridgehead on the morning of February 26, inflicting heavy casualties on the German defenders. Cooper witnessed terrible sights: “I was shocked to see a young German soldier sitting fully erect in his foxhole, holding his rifle. He had been struck by a single projectile, and I could see daylight through a two-inch hole in both sides of his helmet and his head.”

From the bridgehead the division moved towards Cologne, assaulting the city on March 3rd. On March 25, after the Allies had crossed the Rhine and were driving deep into Germany, Cooper found himself with CCB near Altenkirchen, some 30 miles east of the Remagen bridgehead.

As he and his driver headed back to their maintenance battalion headquarters they drove along the roadway on the south bank of the Sieg River, heading west. Moving in the opposite direction was a truck convoy of the 1st Infantry Division. Near the crest of a hill, the trucks were exposed to observation from the north bank of the river and German artillery fire. Due to the heavy traffic, the convoy became jammed up and exposed across the top of the hill.

As shelling began, the infantrymen bailed out of the trucks and took cover. One of the trucks was hit. Cooper’s driver stopped their jeep well short of the crest as they assessed the situation. Given the size of the explosions and the time interval between rounds—estimating 20 to 25 seconds—Cooper believed that the Germans were using a single heavy howitzer. With 400 yards of open ground to cross, Cooper carefully calculated the time needed to make their dash to safety.

After another round fell, Cooper and his driver crouched low in their jeep and hit the gas. They reached the crest in 18 seconds. As they passed through a slight depression, their heads below the level of the embankment, another shell exploded about 15 feet from the edge of the embankment, the blast wave passing over them. Through a cloud of dust and debris, they were able to make their escape.

On the night of March 28, Cooper made his run with the combat-loss report stopping by headquarters on his way out to check the G-2’s map for the next day’s objective and the routes the columns would follow. With the situation changing rapidly every day, Cooper and his driver were particularly vulnerable.

The next morning he headed out to catch up with the forward elements of the division pushing the jeep’s maximum speed until they reached a “Y” junction about 10 miles from Marburg, some 60 miles north of Frankfurt. Unsure which was the main road, he directed his driver to the right fork. But after 100 yards, his sixth sense told him to turn around. Back at the junction checking his map, Cooper heard a voice call out, asking if they were from the 3rd Armored. On a small knoll above the roadway were two GIs in an armored car so well camouflaged that Cooper had missed them.

Cooper said that they were with CCB. A sergeant with the 83rd Recon said that they had taken the wrong fork. If they had continued down the right fork they would have come to a German roadblock. Cooper’s experience had sharpened his senses and likely saved their lives.

In another incident, a task force of the division encountered a group of seven German King Tiger tanks, with disastrous results. When the maintenance crews arrived on the scene, they found that the Germans had knocked out 17 Shermans, 17 half-tracks, three trucks, two jeeps, and an M36 tank destroyer—though three King Tigers were also disabled or abandoned in the action.

As the maintenance crews did their work, Cooper gathered the information for his report. He then went to examine the King Tigers. The upper left side of the rear armor on one of them had been penetrated by a 76mm round, passing through the fuel tank and setting the tank on fire. The round had then entered the crew compartment and struck the inside of the faceplate. The projectile then ricocheted around the inside, killing everyone.

Curious about the penetrating power of the German 100-meter version of the panzerfaust, Cooper decided to test it against the Tiger’s armor.

From 30 yards, directly in front of the Tiger, he aimed at the turret faceplate, to one side of the gun mantlet. The anti-tank rocket struck with a tremendous explosion, showering Cooper with small cement particles (the Germans having covered their tanks with a thin layer of cement to protect them from magnetic mines that a daring individual might try to attach). The warhead’s shaped-charge made about a three-quarter-inch diameter hole through the faceplate’s 8.5-inch turret armor. The blast showered the interior with small fragments.

A few days later, Cooper examined a knocked out Sherman. Nearly six feet of the tank’s 76mm gun barrel was missing. There had also been an explosion in the crew compartment. The gun’s breechblock was open, resulting in blast damage to the interior. Cooper wondered if the crew had been firing a round that detonated in the gun tube, the gun’s recoil opening the breech. However, they concluded that a German 75mm round had entered the gun tube and detonated, blowing off the end of the barrel, part of the projectile then traveling down the barrel, through the open breech and killing two of the crewmen.

The bodies of the two dismembered crewmen were still inside the tank. Two mechanics that were sent in to remove the bodies were overcome by the blood and gore. When volunteers were called for to remove the bodies, there were no immediate takers. Even the most hardened members of the unit were not inclined to help.

Finally, a pale thin young man stepped forward. He was a fire-control instrument-repair mechanic with the headquarters unit. A low-key individual, he felt that the individuals deserved a decent Christian burial.

Afterwards, the interior of the tank was scrubbed and disinfected. The gun barrel was replaced and electrical wiring repaired. The entire interior was repainted with a heavy coat of white lead.

The risk to maintenance liaison personnel was always significant. But as the Allies drove deeper into Germany, chaos and confusion increased the threat. At one point, a division liaison officer and his driver went missing. The wreckage of their jeep was discovered alongside a road along with their bodies. They had been beaten, their skulls crushed.

In Lieutenant Cooper’s capacity as CCB’s ordnance liaison officer, he likely witnessed more damage done to American tanks than any other member of the U.S. Army in Europe. Having to prepare combat-loss reports after each action, Cooper became very familiar with the weaknesses and inadequacies of the M4 Sherman medium tank.

While Cooper was very critical of the M4 Sherman’s design, he seemed not to recognize that he was part of its ability to overcome its shortcomings. The Sherman’s mechanical reliability and ease of maintenance and repair, as well as the support of a better logistics system, were qualities that the heavier German tanks—the Panther and Tiger—lacked. The M4 also shared the same hull, chassis, and many parts with other vehicles, such as the M10 and M36 tank destroyers and the M7, M12, M40, and M43 self-propelled artillery pieces.

Also, the U.S. Army’s fighting doctrine did not intend for the Shermans to be used to engage enemy tanks, but to provide infantry support while tank destroyer battalions dealt with German panzers. While the Sherman’s 75mm and 76mm main gun was at a disadvantage when dealing with the frontal armor of the Panther or Tiger, the British sought to provide a solution by mounting a 17-pounder gun on their American-supplied vehicle—the Sherman Firefly—a threat that the Germans recognized as they took special care to target these vehicles.

The key to logistics support for a rapidly moving armored force was the capability of the armored division’s maintenance units to assist the forward elements of the mechanized forces. A task force with 50 tanks moving 30-40 miles a day would see between 15 to 20 tanks drop out during a single day for maintenance and repair—requiring minor fixes or even major repairs. Tanks, half-tracks, and other armored vehicles were subject to heavy wear during everyday operations.

The hard work of battlefield recovery and evacuation, field repairs, vehicle maintenance, and replacement created a strong mutual respect between the combat troops and the maintenance personnel, as they depended on one another for survival.

As part of the spearhead of the First U.S. Army, the 3rd Armored Division destroyed more enemy tanks, and participated in the capture of more prisoners than any other American armored division—the division’s CCB destroyed more German tanks than any other combat command. The division also lost more tanks than any other armored division, but the support of its logistics and maintenance personnel allowed it to always keep driving forward.

A frequent contributor to WWII Quarterly, Allyn Vannoy lives in Oregon and is the author of several books, including Against the Panzers: United States Infantry Versus German Tanks, 1944-1945.

What’s that old sage advice, “Amateurs talk tactics, professionals talk logistics”? I learned that lesson well in the Air Force and often had to deal with those who did not. Few people really get it in practice. Tactics can be sexy, but logistics are for survival. Given the choice, I’d rather survive!

Maintenance (Crew, Organizational and Ordnance level) leads the way for Armor crews, without it our armored vehicles can’t move, shoot or communicate. Great article and my hats off to the maintenance folks.

Gary J Petruska

MSG Retired

19Z5HA8