By Eric Hammel

It was 7 o’clock Israeli time, three hours after dawn on Monday, June 5, 1967. The summer season’s daily thick morning mist was just lifting from the coastal areas, across the breadth of the humid Nile Delta, and along the Suez Canal. The air was calm and the angle of the sun rendered visibility throughout the coastal region as good as it was going to be all day.

Right on time, 40 Israeli combat jets took off from their Negev Desert base as they did each morning. And, as it did each morning, the Israeli formation swept to the west, out across the neutral Mediterranean Sea. To the southwest, Egyptian radar operators noted the regular morning flight and thought nothing of it. In the first place, it was not their job to think. And, in the second place—even with the danger of war breaking out at any moment—there simply was no need to concern higher headquarters with news of what for two full years had been a routine so unvarying that it was possible to set clocks by it throughout the troubled region. In due course, precisely on time, the Israeli jets would dive to wave-top height and turn for home. In a short time, the skies over the southeastern corner of the Med, where Africa touched Asia, would be clear.

Along the Egyptian shore and inland, at all 18 of the Egyptian military air bases scattered throughout upper Egypt and across the uneasy Sinai Peninsula, Egyptian pilots and ground crews were eating breakfast. There had been a dawn alert—there was a dawn alert every day—but no Israeli attack had materialized despite the extremely tense situation along the Egyptian-Israeli frontier in Sinai. Everyone thought the war would have started by now, but it had not. For one more day, the feared Israeli preemptive dawn strike had not materialized, as common wisdom said it must. So, after all, the day’s normal routine had to be played out.

The Egyptian Air Force was ready. Before dawn, dozens of Egyptian combat fighter pilots had been in the cockpits of their jet interceptors, sitting at the ends of the various runways, all on five-minute strip alert. From 4 o’clock until 7:35, pairs of Egyptian MiG-17 and MiG-21 fighter-interceptors had been flying a succession of half-hour combat air patrols along the Egyptian-Israeli frontier in Sinai. But the last patrol fighters had landed, and nearly all the pilots were eating breakfast. Indeed, at 7:40, nearly every pilot in the Egyptian Air Force was eating breakfast.

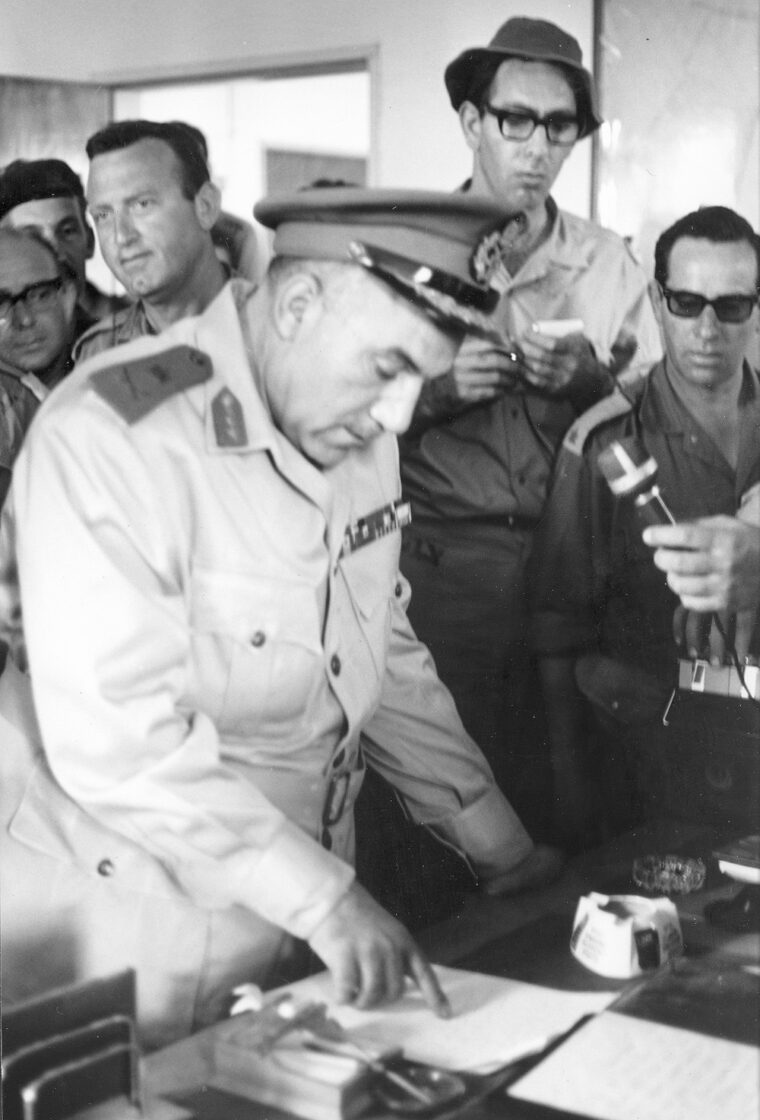

Elsewhere in Egypt, top military commanders and government leaders were on their way to work; most of them would be unavailable to receive information or make decisions until 8 o’clock. The only Egyptian commanders who were focusing specifically on what the Israelis might be doing at that moment were Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer, the Egyptian minister of war, and General Mohammed Sidki Mahmoud, the Egyptian Air Force chief of staff. Together with the Soviet brigadier general who was then serving as senior liaison to the Egyptian Air Force, Amer and Sidki were aloft in a Soviet-built twin-engine Ilyushin Il-14 transport fitted out as a flying command post. Sidki had spent the past hour monitoring transmissions from the combat air patrols along the frontier, but he and War Minister Amer decided to head home at 7:40, five minutes after the last patrolling MiG fighters had touched down. As the Il-14 turned toward Kabrit air base near Cairo, the ground controller reported that there was no traffic anywhere near Sinai, except for the daily Israeli mission over the Med.

At 7:45, precisely on schedule, the Israeli jets on the Egyptian radar screens dived and disappeared below the horizons of all the radar in the area—Egyptian, American, and Soviet. The daily event was duly noted. At the same moment, precisely, the pilot of the Il-14 flying command post reported to General Sidki that, following a brief burst of voices, radio contact with Kabrit had gone dead.

It was at that precise moment that the bombs began to fall.

Tensions had been rising in the Middle East for months before Israel launched her preemptive strike against the Egyptian Air Force on the morning of June 5, 1967. Thanks to an international political process that had gone awry—chiefly because of a weak and vacillating United Nations—Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser had embarked upon a game of intimidation and brinksmanship from which, in the end, he could not be pulled back, and from which Israel would not shrink. At the moment the Israeli bombs started falling, Egypt had amassed more than 90,000 soldiers and as many as 900 tanks on her Sinai frontier with Israel. It was impossible for Israel to wait for the more powerful Egyptian Army and Air Force to strike; she had to strike first. That Israel used her air force to strike the first blow was not a matter of chance; the Israelis had plotted and planned that strike for nearly two decades.

The Rise of the Israeli Air Force

It was an infantryman, Brig. Gen. Chaim Laskov, who had the most profound impact upon the doctrinal development of the Israeli Air Force (IAF). As commander of the IAF from 1951 to 1953, Laskov ordained that Israel build an offensive air force composed entirely of fast, sturdy fighter-bombers capable of both defending themselves and delivering precision bombing attacks upon enemy tactical, operational, and strategic targets and ground forces. The IAF was to be a multipurpose air force, capable of launching surgical reprisal air raids and strategic air offensives, and delivering precision on-call close air support for the ground forces.

Laskov’s was a tall order—beyond the capabilities of most of the world’s air forces of the day—and it remained beyond Israel’s reach throughout Laskov’s tenure because of budgetary constraints and limitations imposed by arms’ producers unwilling to alienate Arab sentiments on behalf of Israel’s survival. However, in identifying the exclusive combat-aircraft type, Laskov had a powerful impact upon the IAF’s strategic outlook, and even upon tactical doctrine.

It remained to others, notably Laskov’s successor, Brig. Gen. Dan Tolkowsky, to try to bring Laskov’s dream to fruition. From his appointment in late 1953, Tolkowsky worked tirelessly to acquire the material and hone the proficiency of his small force of pilots, maintenance technicians, and armorers to world-class standards.

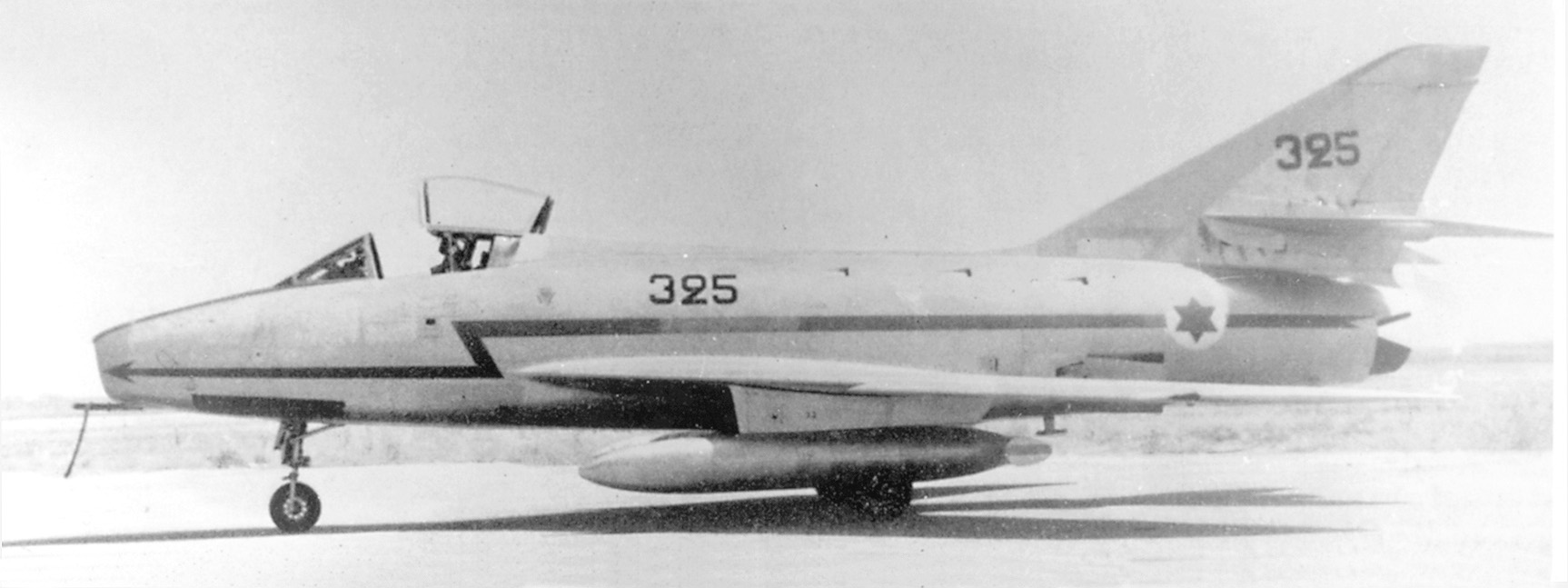

The first jet warplanes ordered by Israel, in June 1952, were French Ouragan ground-attack aircraft, a first cousin of the first-generation Russian and American jet fighter-interceptors that were at the time rewriting combat aviation history over Korea. The first 25 Ouragans were delivered in October 1954; the Israelis also acquired British Meteor jet trainers, some of which were converted for combat purposes. Next, modern French Dassault Mystère-IV fighter-bombers were delivered in April 1956. Not without considerable forethought, each Mystère was armed with two 30mm cannon that were as well qualified to disable or destroy the tanks of the day as they were to take on anything that flew. They could also carry a thousand kilograms of mixed bombs and rockets beneath their wings.

The IAF had 53 operational jet fighter-bombers (and about 50 piston-powered warplanes) by the time Israel joined France and Britain in the November 1956 Suez-Sinai Campaign to re-internationalize the Suez Canal. Although the IAF was vastly outnumbered by the Egyptian Air Force, it quickly gained air supremacy over Sinai; this was due to its overwhelming edge in the quality of its personnel. Leading up to the Sinai Campaign, the head of the IAF’s Fighter Command, its operational arm, was Colonel Ezer Weizman, a bear on pilot selection and training and a true visionary with respect to maintenance and ordnance. It was Weizman’s observation that an air force is not measured in battle by how many planes it carries on its roster, but by how many armed combatants it can get into the air.

Following the 1956 Sinai Campaign, it fell largely to Colonel Weizman to analyze the use of air power in Sinai and to make recommendations based upon the findings. An inevitable result of the study was an energetic aviation modernization program. It also fell to Weizman, following his elevation to the post of IAF commander in 1958 with the rank of brigidier general, to oversee the procurement of new weapons systems.

The highlight of Brig. Gen. Ezer Weizman’s long tenure as IAF chief was his unremitting drive to further improve the overall quality of Israel’s only truly strategic combat arm. While all of Israel’s other military arms were oriented solely toward the tactical and operational levels of fighting, the IAF’s most important mission in time of war was the destruction of the strategic war-fighting assets of one or more enemy nations at once—plus tactical and operational coverage of the battlefield.

Of all of Israel’s combat arms, the IAF possessed the greatest responsibility for undertaking preemptive attacks against the enemy at the outset of a war. Israel’s bedrock preemptive strategy had evolved rapidly since Israel achieved nationhood in 1948, but it took Ezer Weizman’s blunt articulation of the principle—“Israel’s best defense is in the skies over Cairo”—to make a strategic preemptive air strike the IAF’s chief mission in life.

In addition to modernizing, the IAF needed to grow, for it was equally plain to see that the Sinai Campaign had only delayed an ultimate day of reckoning between Israel and Egypt. The Egyptian armed forces were certain to expand in order to surpass Israel’s, so there would be more for the IAF to do in a future war. Over the years, Israel was able to acquire several hundred first-line fighter-bombers from France—the only aircraft-producing nation in the world that was willing at the time to defy the Arab boycott against Israel.

In 1966, Ezer Weizman was replaced as head of the IAF by an equally skilled pilot, Mordechai Hod. Although Hod agreed in principle with every program his predecessor had set in motion, he was even more ardent than Weizman in his shared view that the IAF needed to develop its people to their highest potential. His main task—and outstanding accomplishment—was to see to it that the IAF achieved the fastest combat turnaround capability in the world. Due to Hod’s relentless pursuit of excellence beyond the cockpit, Israeli ground crews could rearm and refuel a jet fighter-bomber in literally minutes, as measured against a worldwide standard of as long as several hours.

If the IAF had been a decent regional air force leading up to 1956, it quietly—in fact, secretly—became very nearly the best in the world leading up to 1967. Absolutely nothing was left to chance. Feeling that war with Egypt was inevitable at some unknown future date—or the very next minute—IAF squadrons relentlessly rehearsed the many strategic, operational, and tactical missions they might have to undertake at a moment’s notice. Wide-ranging and ongoing intelligence operations resulted in plans that were updated almost weekly and which could be altered at a moment’s notice, even as individual aircraft were screaming down on their targets. At every minute of every day, a sufficient number of Israeli pilots was on strip alert, sitting in the cockpits of their modern fighter-interceptors, ready to launch into action at the first hint of hostile intent. Indeed, it is likely that never a moment passed when Israeli fighters were not actually airborne. The entire organization—pilots, maintenance crews, armorers, controllers, everyone who was on duty at a given moment—was keyed up to a war pitch, absolutely prepared to fly straight into an offensive or a defensive fight.

Israel’s First Wave of the Surprise Attack

On the morning of June 5, 1967, as General Mohammed Sidki Mahmoud stared at a dark cloud expanding from the ground upward over the huge Cairo West airport, nine of the 18 Egyptian front-line airfields—from mid-Sinai to west of Cairo—were each struck by four Israeli jet fighter-bombers. Minutes later, a tenth Egyptian runway, at Fayid, also was struck.

Each quartet of Israeli strike aircraft arrived low over its target precisely on time, at the exact moment detailed in the plan the IAF had been formulating for years. They had taken off from their home bases at precise intervals and had adhered to precise navigational and air-speed criteria even though they were all flying at extremely low altitudes. So as not to alert the enemy, the routes of all 10 flights in the leading wave had been circuitous, away from all manner of prying eyes and eavesdropping electronics.

The precautions worked. As a result, the runways at nine Egyptian air bases were disabled by Israeli bombs at precisely the same instant, and Fayid was disabled minutes later, also right on schedule. Each and every bomb exploded, and each one did so precisely on cue.

Many of the Israeli bombs were French-manufactured 1,200-pound concrete busters equipped with small internal rockets designed to both retard forward momentum and drive the bomb straight downward into and even through a concrete runway surface. A time-delay fuse prevented the bomb from going off until it was as deep as it could go—the better to inflict lasting damage, to blow deeper, less easily repairable holes. Young Israeli pilots—their average age was 23—whose fighter-bombers were rigged out with standard 500- and 1,000-pound high-explosive “iron” bombs, enhanced the penetration characteristics of the payloads their airplanes were carrying by swooping up and then steeply down at the last moment so they actually could dive-bomb the runways. Most of the bombs in the initial delivery detonated within a heartbeat, but a number of the bomb fuses were set to explode at varying times, some long hours after the Israeli raiders had departed. Thus maintenance crews would be prevented from safely filling craters—or wanting to.

After the Bombs, Strafing

As the initial flights of Israeli fighter-bombers recovered from their bombing runs, they turned back and, still at very low altitude, launched French-built air-to-ground missiles and sprayed 30mm cannon shells at every Egyptian airplane upon which the pilots could lay their sights. The employment of the air-to-ground missiles on strafing passes was particularly diabolical in that the missiles’ infrared, heat-seeking system was especially effective against quick-reacting Egyptian pilots who were just starting engines when the missiles were fired. The missiles, of course, were designed to home in on jet-engine heat signatures.

If there were no unsmitten Egyptian aircraft within reach, the Israeli strafers shot up vehicles and buildings. Each Israeli fighter-bomber made two strafing passes—or maybe three, if there was time. By dint of unbelievably accurate intelligence and unbelievably detailed briefings, the Israeli pilots—who, after all, were streaking in at hundreds of miles per hour—left untouched virtually all of the many dummy aircraft the Egyptians had placed in many airfield revetments.

As the first wave of Israeli jets was arriving over its targets—right on the deck, well below Egyptian radar horizons and nearly 4,000 feet lower than the effective altitude of Soviet-supplied SAM-3 antiaircraft missiles—the second fighter-bomber wave was halfway to its targets and the third wave was just getting airborne. By the time the third wave reached Sinai and Egypt, the breadth of the attack would have expanded to encompass several additional Egyptian airfields.

The only Egyptian aircraft in the air at the moment the IAF was unleashed were General Sidki’s Il-14 and four unarmed jet trainers—an instructor shepherding three student pilots. The Il-14 evaded the Israeli fighter-bombers, but the trainers all were downed, almost as an afterthought. The first flight of four Israeli Dassault Mirage-IIICJ delta-wing fighter-bombers to reach the air base at Abu Sueir bagged four MiG-21s that apparently just happened to be taxiing routinely toward the end of the runway.

The first Israeli jets to strike Cairo West and nearby Beni Sueif air bases dropped their bombs and then returned specifically to destroy the 30 huge Tupelov Tu-16 Badger twin-jet medium bombers composing the two squadrons of the Egyptian Air Force’s Strategic Bombing Regiment. The eight Israeli Mirages cratered all the runways at both bases and then destroyed 16 of the medium bombers with their 30mm cannon. They thus cut the heart out of the strategic bombing threat against Israeli cities. Three minutes later, a second relay of eight Israeli Mirages bombed the runways again and then destroyed all the remaining Tu-16s, also with 30mm cannon fire.

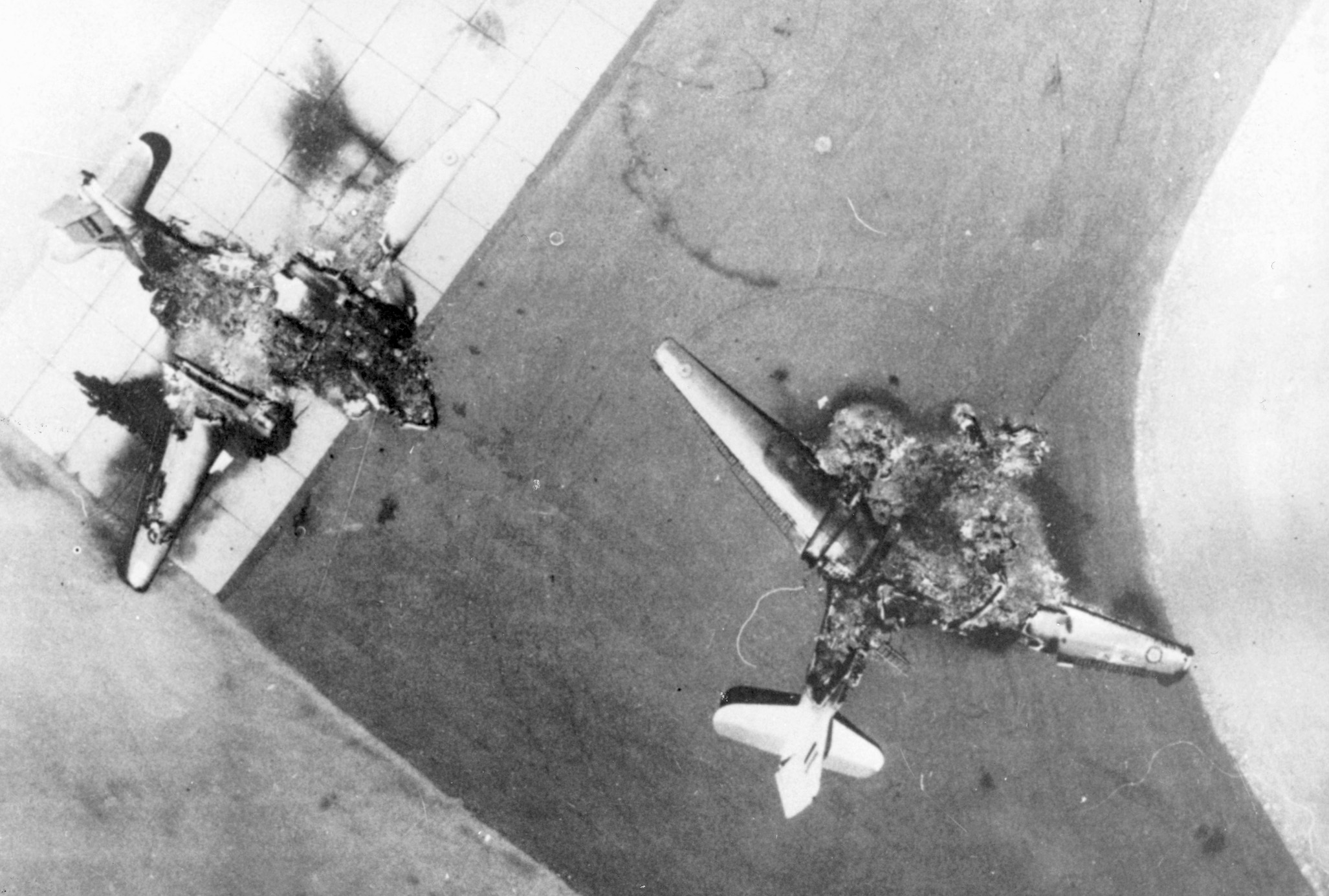

Egyptian air bases west of the Suez Canal that were attacked by the first wave of Mirages and Dassault Super Mystère fighter-bombers were Cairo West, Kabrit, Abu Sueir, Beni Sueif, Fayid, and Inchas. Simultaneously, Israeli Ouragan ground-attack jets and Mystère fighter-bombers attacked all four of the Egyptian forward air bases in Sinai—El Arish, Jebel Libni, Bir el-Thamada, and Bir Gifgafa. In fact, the Sinai attack developed so quickly that two MiG-17 ready fighters at Jebel Libni were incinerated by the second pair of Israeli Mystères before the Egyptian pilots in the cockpits could even start their engines.

In the meantime, the lead pair of Mystères over Jebel Libni dropped their bombs on the runway and then went around to destroy many of the 13 remaining MiG-17s and MiG-19s parked in the base’s revetments. In the end, the four Mystères destroyed every Egyptian fighter at Jebel Libni with cannon fire before they turned for home. Not by accident, the carefully briefed, exhaustively practiced Mystère pilots cratered only half of Jebel Libni’s 7,000-foot runway. The 3,500 feet of the runway they intentionally left intact was just long enough to support operations by Israeli transport planes after the projected capture of the base by Israeli ground forces. A strike at dusk by Mystères and Ouragans was scheduled to sow small delayed-action antipersonnel bombs all across Jebel Libni to slow or prevent altogether Egyptian efforts to repair the cratered half of the runway.

The six MiG-17s lined up in revetments at the Sinai coastal air base at El Arish were destroyed by precision rocket fire from four Super Mystère fighter-bombers in order to prevent serious damage to the facilities. The runway at El Arish was spared entirely from bombing because Israeli ground forces planned to overrun it in only one day. Then the base was slated to become a forward medical air-evacuation depot.

The runways at the two remaining Sinai air bases—Bir Gifgafa and Bir el-Thamada—were routinely cratered. All of the aircraft at the two bases—transports and a few helicopters—were destroyed with 30mm cannon fire by the attacking Mystères.

The initial Israeli attack wave departed from the target area after only seven minutes. The average return flight to air bases in Israel was 20 minutes. Once the fighter-bombers were on the ground, waiting ground crews were able to rearm them with bombs and cannon ammunition—even refuel them—in a world-record eight minutes. Thus, within about an hour after launching for the first sortie, the initial attackers were ready to launch again. Each Israeli warplane was capable of flying eight sorties per day, a stunning accomplishment to which no other air force in the world came close.

Each wave of Israeli fighter-bombers arrived precisely 10 minutes after the preceding wave. The Israeli pilots were restricted to just seven minutes over their targets—barely enough time to drop bombs and carry out two or three strafing runs. The only opportunity the surviving Egyptian aircraft had to attempt to get airborne was during the three-minute lulls the Israeli planners had factored in for navigational errors. Over the course of the first 80 minutes of the war, only eight pairs of Egyptian interceptors attempted to scramble aloft despite falling bombs and runway damage. However, Israeli jets streaking in to bomb or strafe the air bases destroyed every one of them. Indeed, not one of the Egyptian jets survived the ordeal of taxiing as far as the ends of their runways.

Twelve MiG-21s and eight MiG-19s had been redeployed a few days earlier to the Hurghada air base in southern Sinai, following a number of feints by Israeli jets in that direction. This potentially formidable force of first-line fighter-interceptors was launched as soon as news of the Israeli strike reached its base. After waiting over Hurghada in vain for a while, it was vectored north to relieve the carnage over the Suez Canal. At about 8:30, as the 20 newly arrived MiGs curiously overflew the ruined and silent Abu Sueir air base, they were bounced by the 16 Israeli Mirage fighters charged with guarding the next attack wave. The aggressive Egyptian pilots put up a ferocious struggle, but four of the MiGs were shot down in short order by cannon fire and heat-seeking air-to-air missiles. The remaining MiGs, which were critically low on fuel, disengaged and eluded the Mirages. Only then did the Egyptian pilots learn that Israeli bombs had disabled every one of the runways within range. None of the MiGs had enough fuel to return to Hurghada, so the Egyptians scattered and tried to set down wherever they could. Most of the MiGs barreled into runway craters or other obstructions and were destroyed or seriously disabled.

Although launched from the Negev Desert’s Hatzerim air base at the same time as the first attack wave, 15 rather slow twin-engine Israeli Sud Aviation Vautour-IIA light attack bombers were obliged to fly a long, circuitous route to attack the Egyptian air bases at Ras Banas and Luxor, the most distant targets of the day. After skirting the Saudi Arabian coast and flying most of the length of the Red Sea on the deck, the Vautour squadron turned west and split up after making landfall over Egypt. Their objectives were the runways from which the Egyptian Air Force had been bombing Yemeni Royalist forces with impunity for several years. After the runway at Ras Banas was put out of commission by 500-pound high-explosive bombs, the 16 Ilyushin Il-28 Beagle light bombers parked in neat ranks there all were destroyed by 30mm cannon fire from only two of the Vautours.

At Luxor, however, heavy antiaircraft fire rose to challenge the Vautours as they turned back after bombing to strafe the MiG-17 squadron parked there. One of the Vautours lurched to the side and lost altitude after being hit, but the pilot intentionally flew his crippled jet into a covey of four parked MiGs, which erupted in a huge fireball. The remaining Vautours used up their 30mm ammunition on the remaining MiGs and the base facilities and then returned to Hatzerim at high altitude.

During the morning’s second 80-minute strike sequence, the Egyptians managed to get eight MiGs airborne, mostly from Abu Sueir. Two Israeli Mystères were downed as they arrived to carry out follow-on attacks, but all of the Egyptian planes were shot down by members of the Mirage squadron responsible for providing top cover. The Israelis all used their 30mm cannon, which they preferred to the French-built air-to-air missiles with which their fighters were also equipped.

The only Egyptian plane to land safely during this period was General Sidki’s. The Il-14 command post finally set down at Cairo International Airport at 9:45, after being turned away from a dozen unserviceable runways in the expanding battle zone. In the two hours Sidki’s plane had been flying from pillar to post in search of a safe haven, Sidki’s guest, Field Marshal Amer, the Egyptian war minister, had been out of effective touch with his field commanders—an unexpected bonus the Israeli planners of so much mayhem would have taken great satisfaction and joy from knowing at the time.

The Decimation of the Egyptian Air Force

By the time the second attack sequence ended at 10:35, at least 13 of the 18 Egyptian air bases in Sinai and upper Egypt were nonoperational, and five outlying or minor airfields—none of which housed combat aircraft that day—were due for destruction by midnight. The only front-line air base in the region that would be left unscathed by the following morning—intentionally, at that—was El Arish.

More than 250 Egyptian aircraft had been destroyed or severely damaged. The losses included up to 75 of 150 MiG-15 and MiG-17 ground-support fighters, 20 of 80 MiG-19 fighter-interceptors, 90 of 120 first-line MiG-21 fighter-interceptors, an estimated 10 of 30 Sukhoi Su-7M ground-support aircraft, as many as 27 of 40 Il-28 light bombers, all 30 Tu-16 medium bombers, and about 25 assorted transport planes and helicopters. In addition, 23 radar installations and antiaircraft missile sites had been destroyed or incapacitated. Approximately a hundred of Egypt’s 350 qualified air combat pilots were dead, and many more had been injured, mostly in strafing attacks. Thus, by 10:35, the Egyptian Air Force was no longer a factor in the war that by then was embroiling this pivotal corner of the Middle East.

Balanced against the Egyptian Air Force’s horrific demise, the Israeli Air Force lost 19 of its own bombers and fighter-bombers in the morning assault. However, only one Vautour was shot down by ground fire and two Mystères were downed in air-to-air combat. The rest were operational losses.

A number of attacks still remained to be launched against the Egyptian Air Force, mainly missile sites and several outlying air bases. But, owing to the exceptional success of the preemptive strike, by midday the bulk of the Israeli Air Force was free to destroy the Jordanian, Syrian, and Iraqi Air Forces, and to engage directly in the destruction of Egyptian armored formations in the Gaza Strip and across Sinai.

Eric Hammel is a professional military historian with nearly 30 books and many articles and commentaries to his credit. He also edits and publishes military history books, and has appeared on a number of television programs related to military history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments