By Blaine Taylor

By the late summer of 1814, the invading British Army had routed the entire American Army—both federal and state troops—on the Eastern Seaboard of the United States. At the Battle of Bladensburg, on August 24, the Redcoats mockingly dubbed their victory “the Bladensburg Races” because the Americans ran away so fast. That night the British entered the eerily deserted capital of Washington, D.C., and set various public buildings on fire, including the President’s Mansion, the Capitol Building, the Library of Congress, the Treasury Building, and the Washington Navy Yard.

The rest of the nation’s eastern cities lay equally open to the invaders’ heel—Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and Annapolis were high on the list—but Baltimore came before them all as the ship-building center the British angrily called “that nest of pirates.” It was there that American privateers launched the famed “Baltimore clip ships” that sailed boldly into Great Britain’s home waters to strike at her shipping. Because they were both lighter and faster than King George III’s vaunted “walls of wood,” the American ships evaded the Royal Navy effortlessly, coming and going wherever they pleased.

In response, the British planned to take Baltimore and burn it to the ground—even private homes and businesses—which they had neglected to do in the District of Columbia, where only official structures were torched. The British meant to do to Baltimore what the ancient Romans had done to their mortal foe, Carthage: inflict total, catastrophic destruction, with the hated privateer ships hauled away as prize booty. But first they had to take the city.

Militia Hold Back the Red Coats

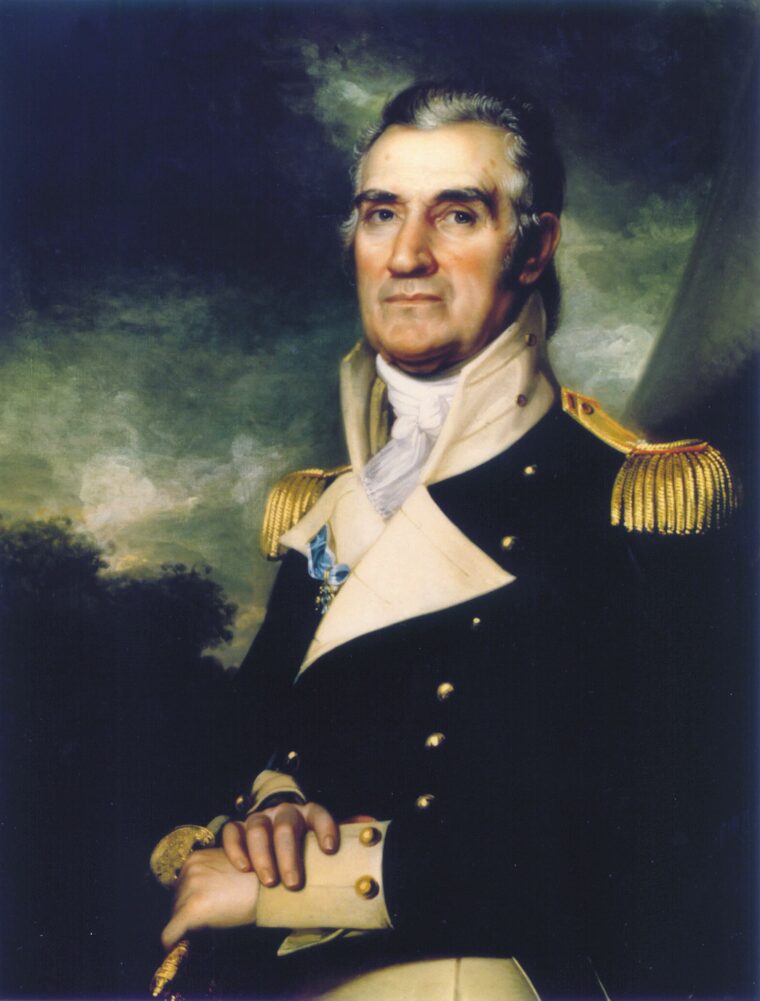

In overall command of American forces at Baltimore was Maryland militia Maj. Gen. Samuel Smith, who guessed correctly that the British would land at North Point and begin marching inland. On September 12, a waiting militia force led by Brig. Gen. John S. Stricker blunted the British spearhead at the Battle of North Point. Adding insult to injury, the British commander, Maj. Gen. Robert Ross, was killed early in the fight. Hearing gunfire to his front, Ross rode out to investigate. Two teenage saddler’s apprentices from Baltimore, Daniel Wells and Henry McComas, were among the militiamen lying in wait for the British. One of them fired the fatal round that struck Ross in the right arm and passed through his chest and lungs. Neither boy lived to receive credit for the general’s death; both were killed by British return fire.

Colonel Arthur Brooke of the 44th Regiment of Foot took over for Ross. After driving off the American militia, he had the army camp for the night and then pushed on toward Baltimore the next day. There he ran up against Smith’s eastern defense line, which linked the inner harbor with the fortified heights of Commodore John Rodgers’ bastion, Loudenslager, and Hampstead hills in east Baltimore. With about 4,500 British regulars, Royal Marines, and Navy tars well in hand, Brooke stared up at 20,000 American militiamen and sailors armed to the teeth behind strong breastworks. These men were determined not to run away as their comrades had done at Bladensburg—they were defending their homes and families.

Brooke tried to turn Smith’s left flank, but was shadowed by tailing American forces. In desperation, he planned a night bayonet assault and called on British Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane of the Royal Navy to create a diversion by bombarding the American entrenchments for him. Just then, Cochrane had his hands full preparing a much larger bombardment of the imposing structure guarding the mouth of the Baltimore harbor, Fort McHenry. The fort, commanded since 1813 by Major George Armistead, sheltered 700 regular infantrymen and artillerists in three regiments, as well as around 300 additional militiamen and 23 cannon.

Fort McHenry: A Well-Manned Fort With a Fatal Flaw

Ninety percent of Smith’s overall force at Baltimore was raw, untrained militia, most of whom had never fought anyone, let alone the best trained troops and sailors on earth. They had not yet seen action, and drilling had been infrequent at best. Armistead’s professionals at Fort McHenry assumed even more importance, for they alone could be counted on to stand fast under fire: a salient virtue in light of the British naval bombardment. Their commander, Armistead, was an extraordinary soldier. A career Army officer, he was born in 1779 at New Market, Va. A second lieutenant at the age of 18 in the elite artillery corps, he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel within 18 years, a remarkable progression in those days. He was assistant military agent at Fort Niagara, N.Y., from 1802 to 1807, and from 1809 to 1812 he served his first tour of duty at Fort McHenry as assistant commander. In 1812, he returned to Fort Niagara, being promoted to major of artillery in 1813 and winning military honors at the Battle of Fort George. In July of that year, Armistead assumed full command at Fort McHenry and immediately joined Smith in preparing to defend the city from British assault.

In the build-up to the battle, Armistead suffered from his solitary knowledge of a terrible secret, namely, that Fort McHenry’s brick magazine was not bomb-proof—a direct hit could blow the entire fortress to bits, killing the garrison within. The fort, one of several such bastions built up and down the East Coast to defend against seaborne invasion, had its origins in 1776 with the construction of Fort Whetstone on the same site. Although the British never challenged it during the American Revolution, it was thought wise to improve it anyway, and construction continued from 1794 to 1805. In 1798, the fort was renamed after Baltimore native James McHenry, then serving as secretary of war in President George Washington’s cabinet.

The original plans for the fort were drawn up by a French Army engineer officer, Jean Foncin. Military engineers of the era liked the five-pointed star shape of the fort because it enabled soldiers to mount a crossfire from the ramparts against the enemy below. A row of tall trees, houses, sheds, barracks, storehouses, embankments, and a wooden rail fence stood at different points around the fort, while an expanse of broad, flat lawn ran down to the water’s edge. Solidly built dirt walls faced with red brick comprised the high parapets and ramparts guarding the fort’s 26.5 acres, which also included a powder magazine, barracks, and guardhouse. The fort’s main armament consisted of guns removed from the damaged French warship La Poursuivante, which had limped into Baltimore harbor after fighting it out with the Royal Navy’s HMS Hercules during the Napoleonic War.

On September 10, Brig. Gen. William Winder, commander of the 10th Military District, discovered on an inspection tour of nearby Fort Covington that half of its 93 men in the command of Captain William Addison’s Sea Fencibles, or Coast Guard, were sick with fever, and promptly reported this to Smith. The latter, concerned that Fort McHenry’s rear be adequately protected, ordered Commodore Rodgers to send a naval detachment to reinforce Fort Covington and ensure that Battery Babcock’s guns were properly manned. That night the commodore notified Lieutenant Solomon Rutter, commanding the battery across the harbor at Lazaretto Point, that 12 British sailing ships had been sighted at Annapolis, and smaller vessels were seen heading up the Chesapeake Bay.

Preparations for Battle

The next day, Baltimoreans were still at church services across the city when at 1:30 pm the alarm gun on the courthouse green sounded a signal of three blasts. Citizens cried out, “The enemy is upon us! Every man to his appointed station!” In front of the Wilkes Street Methodist Church, the soldier-worshippers had stacked their arms in neat rows. As the cannon blasts startled the congregation, the minister halted his sermon, closed his Bible, and intoned,“My brethren and friends, the alarm guns have just fired. The British are approaching, and commending you to God and the Word of His Grace, I pronounce the benediction, and may the God of battles accompany you.” The Reverend John Gruber at the Light Street Methodist Church closed with equally defiant words: “May the Lord bless King George, convert him, and take him to Heaven—as we want no more of him here!”

Excitement reigned supreme in the streets, as citizens scampered about to join their militia units and rushed to the top of Federal Hill, where an incredible sight greeted their eyes: dozens of British warships riding at anchor 12 miles away down the Patapsco River at Old Roads Bay off North Point—just as Smith had predicted. The British fleet standing off North Point consisted of 50 capital ships and 86 smaller craft, for a grand total of 136, probably the greatest single fleet ever assembled in Maryland waters. Major vessels included five bomb ships, a single rocket-launching ship, five schooners, 10 ships of the line, six sloops, 21 frigates, and a lone tender. In terms of firepower, the fleet encompassed a massive 1,824 guns of all calibers, weight, and shot.

In keeping with a predetermined plan, Rodgers and his sailors began sinking two dozen merchant vessels in the channels between Fort McHenry and the two shore batteries, making the waterways unnavigable by the larger British ships. Meanwhile, Smith was handed an urgent message from Armistead: “From the number of barges and the well known situation of the enemy, I have not a doubt that an assault will be made this night upon the fort.”

“We’ll take it in two hours!”

Back on the Patapsco River, Cochrane had weighed anchor around 1:30 pm, after seeing that Ross, and was well on his way up North Point Peninsula, and headed toward Baltimore, shifting his flag from the Tonnant to the shallower draft frigate Surprise. Even as he ordered his bombardment squadron to get underway upriver to fulfill his part of the two-pronged offensive—the conquest of Fort McHenry and Baltimore’s inner harbor—Cochrane was ignorant of the fact that he had already lost his experienced ground commander, Ross, and that the much less capable Brooke was about to wage the first land battle of the current campaign.

Cochrane was eager to assault Fort McHenry, boasting, “We’ll take it in two hours!” In his view, blasting the earth-and-brick fort to powder would be child’s play and, indeed, he had formidable naval muscle to back up his boast. Cochrane took with him the frigates Madagascar, Hebrus, Severn, Havannah, Euryalus, Fairy, Rover, Wolverine, and Seahorse; the schooner Cockchafer; and the real terrors of the bombardment section, the rocket ship Erebus and the bomb ships Meteor, Volcano, Aetna, Terror, and Devastation. Cochrane had at his disposal a total of 364 guns of all sizes and weights, including the terrifying Congreve rockets. Surely a little mud fort could not withstand the greatest floating siege artillery the world had yet known. Fort McHenry must fall.

Cochrane had been forced to leave the larger battleships behind because they could not make it up the shallow Patapsco, which was full of shoals that threatened to ground the ships. Sailing on Surprise, which was commanded by newly promoted Captain of the Fleet, Admiral Edward Coddrington, Cochrane noted the backbreaking work it took for his tars to warp slowly upriver. Even with three experienced pilots to guide them, Seahorse ran aground and was stuck for four hours, while Captain James Nourse sent out boats to take soundings in a futile effort to prevent any more such groundings. At around 3:30 pm, as the Battle of North Point was ending, Surprise dropped anchor five miles below Fort McHenry, along with the frigates and brigs. The rocket ship Erebus and her five sister bomb ships went in another 21/2 miles where they, too, dropped anchor.

Trading Fire

The main act of the drama was now at hand. At Fort Covington, Lieutenant Henry Newcomb entered in his log for September 13: “At 6 am, five bomb ships and ships of war got under way and took their station in a line abreast of Ft. McHenry.” The British ships were now 21/2 miles south of Fort McHenry and three miles from Fort Covington. In overall command, Cochrane left operational command to Coddrington. From their vantage point before the opening of the bombardment the two could see Fort McHenry, its auxiliary forts, and the shore batteries, as well as the masts of the frigate Java, the sloops of war Java and Ontario, and several merchant vessels and privateers, all tempting prizes for the two veteran sailors.

While they watched, American sailors completed sinking the final block ships in the harbor to prevent access to Fells Point and the city itself. Included in the underwater obstruction were the vessels Temperance, Father and Son, Packet, and Enterprize, but not the 130-foot-long steamboat packet Chesapeake, which was merely anchored sideways above the sunken ships. Baltimore’s fortifications were now as complete as Smith could make them.

At 6:30 am, the bomb ship Volcano lobbed two mortar rounds to ascertain the target’s range, but these fell short of the fort and she and the other vessels maneuvered closer. Led by Cockchafer, the British frigates and schooners let loose a series of broadsides at the fort and its sister fortifications. The noise of the pounding shook the city’s windows, roofs, and walls. The fort’s guns were primarily firing 18-, 24-, and 36-pound solid iron cannonballs, and many were mounted on barbette garrison carriages, designed to fire at a horizontal slant. Because of their limited range, they had difficulty in reaching the attacking vessels. Nevertheless, Armistead ordered his guns to return fire, and one onlooker noted with satisfaction, “The whole fort let drive at them. We could see the shot strike the frigates in several instances, when every heart was gladdened. We gave three cheers, and the music played Yankee Doodle.”

Inside the sturdy walls were two furnaces preparing glowing-red iron balls that could be sent skipping across the water to hit and burn through the wooden walls of Cochrane’s hulls. Any mounted British frontal boat assault was extremely risky. Armistead realized this fully, and so did an alarmed Cochrane. These were not the tactics he had planned to use, but he refused to risk having his large sailing vessels sunk by Yankee shore gunners, whose skill and aim proved to be surprisingly accurate. At 9 am he gave the order to withdraw to a point two miles away from Fort McHenry and just out of range of her pesky guns. As his frigates anchored on the Patapsco, the admiral realized that he had just lost the first naval round of the battle for Baltimore. His frigates had been driven off by the American shore defenses, and he had lost their considerable advantage in firepower. Within the first 21/2 hours of the battle, the Royal Navy’s guns had been effectively rendered useless by Smith’s superior planning and the surprising marksmanship of Armistead’s homegrown gunners.

A Frontal Assault Impossible

Having rejected a frontal assault, Cochrane fell back on his one remaining option: a classic naval bombardment by the bomb and rocket ships. He was confident that if he could not take the fort by storm, a sustained, indirect bombardment would reduce the will of the terrified garrison and force its surrender, or else endanger the complex to the point that Smith would be forced to reduce his Hampstead Hill defenses by sending land reinforcements to the fort. While he did not think the defensive line could be taken by frontal assault, Cochrane thought it might fall by being outflanked on its right, at Rodgers’ bastion. This was what Brooke was planning to do that very evening, with a diversion created by Cochrane at the waterline that hopefully would weaken the American line and enable his men to take it with a sudden bayonet attack. It was the method traditionally most favored by the British and most feared by Smith, who prayed that Fort McHenry and the other water defenses would hold out.

Armistead, for his part, was confident that he could repel any ground force attack. If the British were foolish enough to attempt a frontal attack by barge and boats, the American gunners would simply blow them out of the water. Assuming by some miracle that the enemy managed to get ashore in force, the fort’s defenders would stop the invaders at the waterline by pouring withering cannon and musket fire into their ranks from the dry ditch and other emplacements surrounding the fort. Then there was the flat, open ground the invaders would have to cross to reach the walls, exposed to American gunfire all the while. Any survivors who managed to reach the walls would be wiped out by guns carefully placed along the five star points to blast any wooden scaling ladders that might be placed.

1,500 Bombs

As the 25-hour-long bombardment began in earnest, Armistead vowed to keep the British ships as far out to sea as possible. To this end, he increased the effective range of his own guns by the dangerous expedient of using extra charges of powder and elevating the barrels higher to send their rounds farther. Not only did this risk blowing up the guns and killing his gunners, it also proved to be ineffective, for the maximum range of the 24-pounders was 1,800 yards, and the 36-pounders no more than 2,800. The idea of shooting back was good for the morale of his beleaguered artillerists, but not worth risking their lives and expending ammunition that might be needed when a real assault came. Reluctantly, Armistead ordered the Americans to cease fire.

Now the initiative shifted back to the Royal Navy, whose monster ships could hurl rounds weighing 200 pounds from their 10-inch and 13-inch mortars at an astounding 4,200 yards. (Armistead later would estimate that over 1,500 bombs were fired at the fort, with 400 striking on top or inside.) Since the mortars were heavy weapons, it had been necessary for British shipbuilders to construct special supports beneath the weapons to prevent their plunging through the ships’ bottoms or shaking them to pieces from the blasts’ concussion. The mortars were mounted on pivots, with strong, reinforced timber supports built beneath the deck to allow for the great guns’ massive recoil.

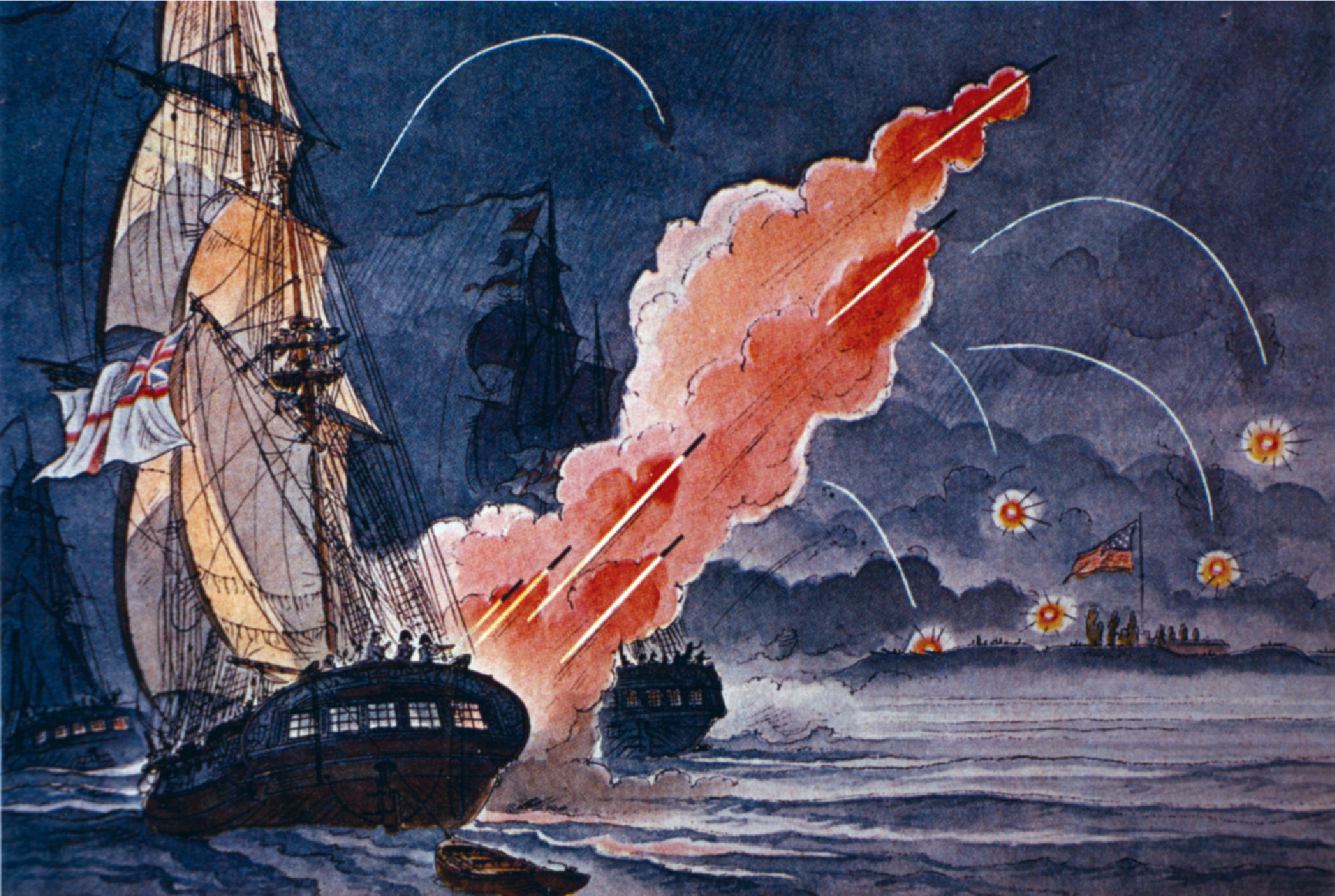

Although Captain Thomas Alexander’s Volcano had fired the first shot at 6:30 am to test the range, the main bombardment was opened in earnest at 7 by Samuel Robert’s Meteor, followed by Richard Kenah’s Aetna, John Sheridan in Terror, and David Price in Devastation. Neither Cochrane nor Coddrington supervised this part of the bombardment; that honor fell to Captain Nourse aboard Severn, and it was under his leadership that the next phase of the battle for Baltimore was waged. Joining the bomb ships were the frigate Cockchafer and the rocket ship Erebus. The rockets’ red glare in the dawn sky was truly frightening, but their fire was wildly inaccurate, and Armistead’s disciplined garrison calmly ignored them.

At 2 pm, the fort’s southwest bastion took a direct hit from a bomb that exploded atop a 24-pounder gun mount, killing Lieutenant Levi Claggett. While the wreckage was being cleared away, a second bomb struck nearby, killing Sergeant John Clemm when a slice of shrapnel cut through his body and buried itself two feet in the ground. In all, four defenders at Fort McHenry would be killed and 24 wounded before the bombardment was over. Unable to fire back, the men inside felt like sitting ducks. As Captain Joseph Nicholson later wrote, “We were like pigeons tied by the legs to be shot at!” The tension was broken when one of the men noticed a rooster strutting along the parapet in the very midst of the bombardment. A soldier vowed that he would buy the rooster a pound cake if they lived through the shelling. He kept his promise, and when the rooster died it was buried with full military honors within the fort. A legend persists that the ghost of the slain Lieutenant Claggett still appears from time to time along the ramparts.

Observing that the hit had caused some consternation in the fort, the British tried again to move closer. Devastation and Volcano, accompanied by Erebus, weighed anchor and sailed toward Fort McHenry. Armistead saw them, and so did Rutter at Lazaretto Point and the American gunboats on the water. When the three British vessels came within range, they all opened fire with a general blast that shook the harbor and surrounding area with a deafening roar. The British were caught by surprise. A gunboat traveling slightly ahead of the trio of larger vessels was hit, and a Royal Marine colonel was sliced in half by a cannonball. Volcano received five hits, while Devastation took a ball through her main topsail and another in the port bow, starting a leak when her timbers were smashed.

“The Enemy’s Barges all in Motion”

Stunned, Nourse ordered the ships to pull back. Now the British naval command found itself in a predicament. Despite the heaviest bombs and rockets they could throw at them, none of the American fortifications seemed to be materially damaged or willing to surrender. His frigate captains offered to take the fort by storm by simply sending in Severn, Havannah, and Hebrus alongside the walls and blasting them to bits, but Cochrane declined. If the fort did not surrender, it would have to be taken by land.

As the bombardment continued, Brooke decided to launch his attack at 2 am on September 14 with all four of his regiments—the 4th, 21st, 44th, and 85th—in a bayonet assault concentrated on Rodgers’ bastion on Hampstead Hill. Brooke asked the admiral for his promised diversionary effort. At 8 pm, Lieutenant James Scott returned with the admiral’s reply. Since the Navy could neither pass the block ships nor subdue the fort, its continued support would be minimal. Cochrane urged the colonel to give up his plan to attack Hampstead Hill and instead re-embark the army at North Point. Brooke met with his officers and argued with them until midnight, then decided to retreat without an attack of any kind on the American line. He advised Cochrane that the retreat would take place the next morning.

Because Cochrane did not receive Brooke’s letter in time, the scheduled naval diversion on Fort McHenry went ahead as planned. About midnight, just as Brooke was adjourning his tumultuous council of war, a flare burst high in the air over the bombardment squadron on the Patapsco. The Ferry Branch, Cochrane reasoned, was the back door into the city’s southern portion via Ridgely’s Cove. A British naval boat division of anywhere from 300 to 1,200 officers, sailors, and Royal Marines—the numbers vary—served as a strike landing force under the command of Captain Sir Charles Napier of the Euryalus. Using muffled oars, Napier’s force assembled quietly alongside Surprise to await final orders from the admiral. They were to row between a mile and a mile and a half out into the Ferry Branch and drop anchor. The bombardment of the forts would begin again at 1 am, and Napier would fire everything he had. It was hoped that the noise would lead the Americans to believe that a sea landing was being attempted from that direction, or that some vessels had gotten in closer to shell them.

The boats got underway at midnight, and the dark, rainy murk was both a help and a hindrance. It concealed the decoy marauders from the enemy, but it also reduced visibility in the pitch blackness to nil. Napier, in fact, had a dual mission. If the diversion succeeded, he was to proceed with a landing. As it happened, he could do neither. Even as his boats were assembling, American Lieutenant Newcomb noted in his logbook at 10 pm: “The enemy’s barges all in motion.” Civilian onlookers from Federal Hill could also see the supposedly secret diversion in progress, despite the rain and haze. Meanwhile, as Napier’s oarsmen pulled ahead in the darkness, 11 of the boats lost their way and rowed instead to the Northwest Branch. Realizing their error at last just off Lazaretto Point, the boats reversed course. Unable to rejoin the rest of Napier’s force, they steered back toward the fleet.

The British Withdrawal

Not knowing that he already had lost the majority of his force, Napier and his remaining nine boats plunged ahead into the Ferry Branch to carry out the plan. They passed Fort McHenry safely, then Battery Babcock, and were approaching Fort Covington to drop anchor when the commander at Battery Babcock, Sailing Master John Adams Webster, was awakened by the sound of oars sweeping by his post. Jumping to his feet, Webster looked into the darkness and saw the lights of gun matches 200 yards away on the water. He ordered all hands to their battle stations and gave the order to open fire. Newcomb, 500 yards upstream, also saw the lights and fired Fort Covington’s guns as well. The surprised Napier was caught in a crossfire. The guns at Fort McHenry opened up as well, and with the British squadron already pounding away, the melee became general.

While the citizens of Baltimore looked on from their rooftops, bombs, signal flares, cannonballs, and Congreve rockets whizzed across the horizon. Webster, who dislocated a shoulder manhandling an 18-pounder into position, sent a messenger back to Lieutenant George Budd asking him to return the 30 men he had loaned him previously. Budd balked, stating that he would keep the men to cover Webster’s retreat. Believing this to be the case, Budd’s messenger panicked, and instead of returning to the battery he went into Baltimore, telling everyone who would listen that the British had taken Webster’s position and were even now marching on the city from the south. General panic ensued.

Meanwhile, the cannonading continued. The British shots were all aimed too high, and most of them missed the forts altogether, although one man was wounded behind Fort Covington and Webster himself was wounded twice in the action. Budd kept firing his own seven guns at Fort Lookout, and the Battle of the Ferry Branch went on for about two hours, with two of Napier’s barges hit by enemy fire. A surprise landing was now clearly impossible, and Napier decided to retire back to the fleet before the first rays of dawn made his nine remaining boats sitting ducks for the Yankee gunners.

Back at Hampstead Hill, Brooke ordered the army roused from sleep, and the men assumed that they were going to storm the American positions at last. But for them the battle was already over. The actual retreat began at 3 am, with pickets left behind to disguise the fact that they were leaving. As the men realized that they were being withdrawn, there was general, malcontented grumbling among them. Second Lieutenant George Gleig, later to become chaplain-general of the British Army, lamented, “Poor Ross, indeed, threw himself away, by exposing himself unnecessarily in a trifling skirmish. Had he lived, the chances are that we should have fought two battles in one day.” But he had not lived, and the British plan to take Baltimore had failed.

An Inspiration for Francis Scott Key

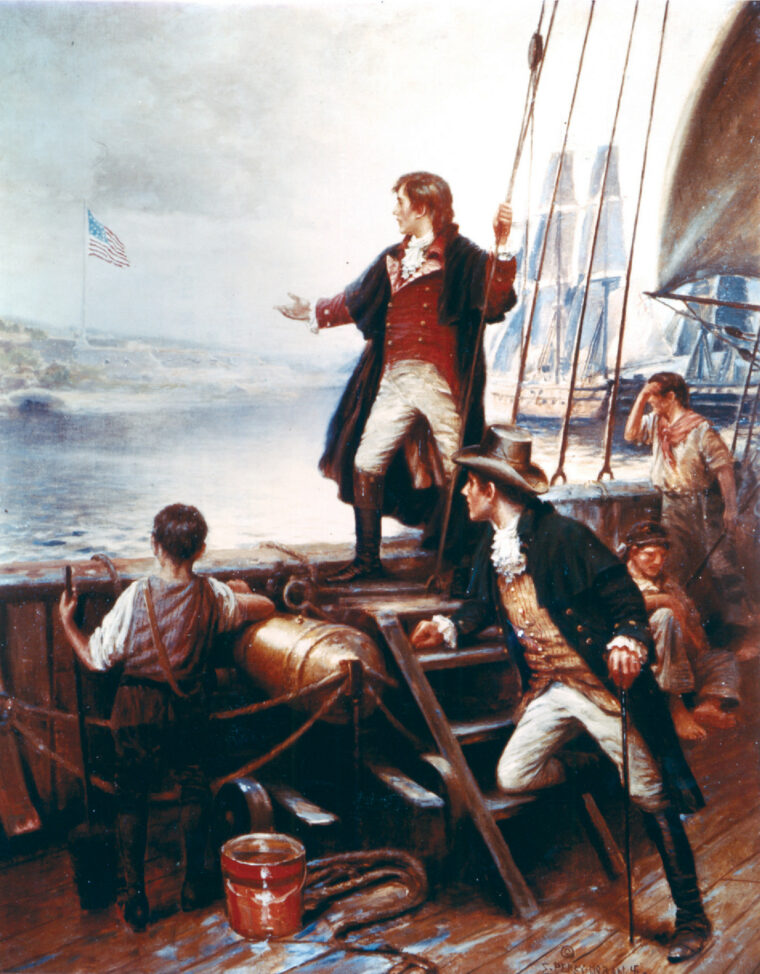

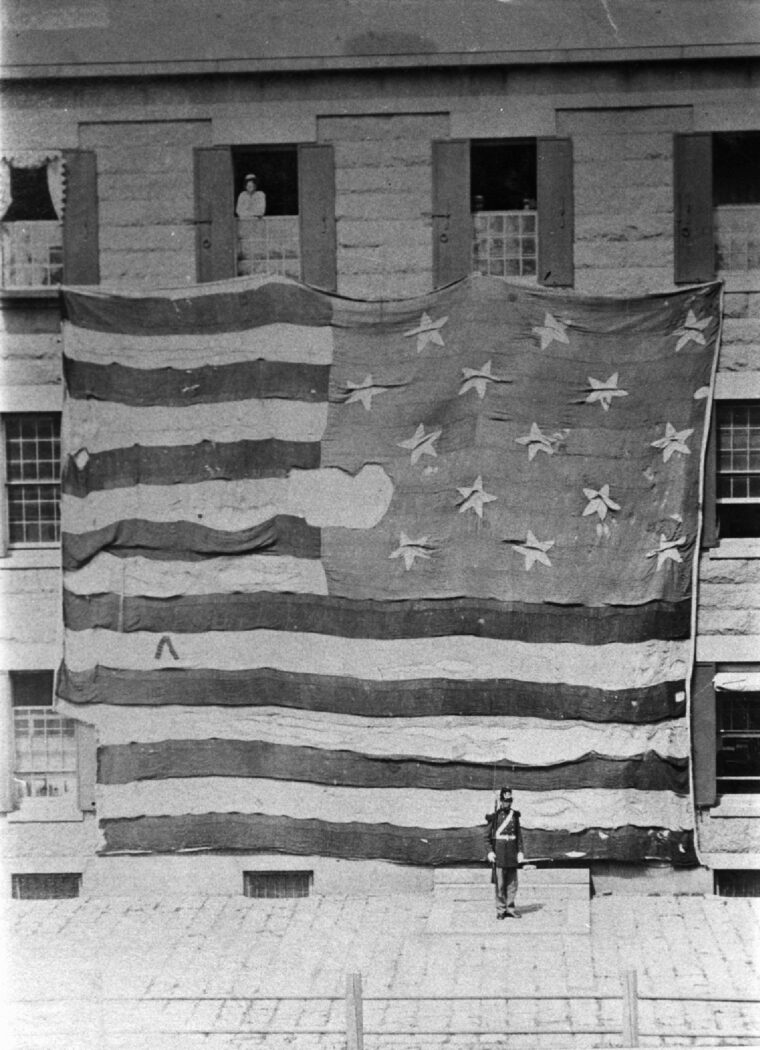

As the British ships began sailing out of the bay, Armistead ordered his men to haul up a huge new flag, 42 feet wide and 30 feet high, that Baltimore seamstress Mary Pickersgill had sewn for them. The giant flag, with 15 stars and stripes and representing the first 15 states (the other three were not yet represented by a star), was clearly visible from the deck of the truce ship Minden, where local attorney Francis Scott Key had spent a sleepless night watching the bombardment as an unwilling guest of the British Navy.

Key had carried a message to General Ross a week earlier, asking him to free American captive William Beanes, a Maryland physician who had been wrongly arrested for treason against the king. Ross was willing to do so, but he could not release the Americans until the planned invasion of Baltimore had been carried out. They had spent an uneasy night tethered to a British vessel eight miles out from Fort McHenry. When Key saw the giant new flag flying above the fort, he was moved to begin a poem, “The Defense of Fort McHenry,” on the back of an envelope. It began: “Oh, say, can you see, by the dawn’s early light …”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments