By Blaine Taylor

Lawyer, poet, and Maryland militiaman Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) was born in Frederick County, Md. He graduated from St. John’s College in Annapolis, where he remained to study law. In 1801, he opened a legal practice in Frederick with fellow law student Roger B. Taney, later chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, before moving to Georgetown to continue his practice. Years later, as an assistant U.S. attorney in Washington, D.C., his most famous case involved the prosecution of Richard Lawrence, an unemployed house painter who became the first attempted presidential assassin in American history when he tried to fire two shots at Andrew Jackson, hero of the War of 1812. Found not guilty due to insanity, Lawrence was committed to an insane asylum.

[text_ad]

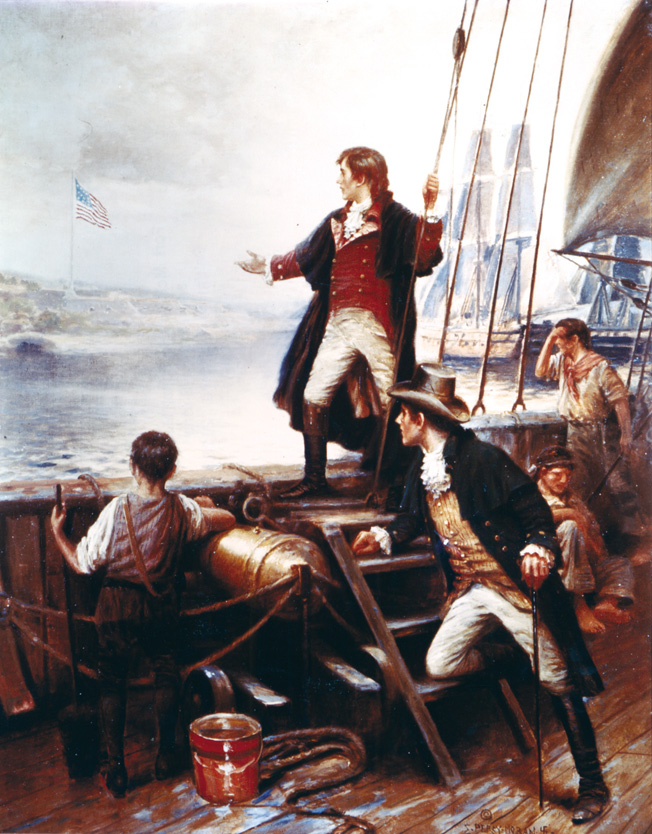

When Upper Marlboro, Md., physician William Beanes was seized by the British following the Battle of Bladensburg in August 1814 and accused of committing treason against the Crown, Beanes’s friends asked Key to approach Maj. Gen. Robert Ross, the British commander, under a flag of truce to seek the elderly doctor’s release. Accompanying Key on his mission was Colonel John S. Skinner, a government agent for prisoner exchange. Like Key, Skinner was a practicing attorney and the successful publisher of American Farmer and American Turf Register.

Key had been authorized by President James Madison to secure the release of Dr. Beanes after his run-in with some drunken British Army stragglers whom he had arrested for pillaging his home on their march back to the Royal Navy troop transports at Benedict after torching Washington, D.C. Ross, wrongly believing that Beanes was a Scottish-born British citizen (he was actually a third-generation American), had intended to deport him to British territory at Halifax, Nova Scotia, for trial, but Key and Skinner persuaded the general to release him after the bombardment of Fort McHenry. Thus, all three men remained captive witnesses to the grand spectacle that led to the writing of Key’s epic poem.

Where Was Francis Scott Key?

One of the many controversies surrounding the incident is where Key’s vessel was located. Baltimore-born historian Walter Lord placed the sloop on the eastern side of the present-day Francis Scott Key Bridge, anchored on Old Road Bay off North Point (today the site of the Veterans Administration facility at Fort Howard) with the main British fleet, and thus not with the bombardment section six miles closer to Fort McHenry. Key’s ship, which some accounts call the Minden, was eight miles distant. A May 5, 1979, letter from the Public Record Office in Surrey, England, stated that “in all probability, Key was still on board the Surprise on the 14th, and the sloop in company, with Surprize’s party on board.”

The mammoth painting by George Grey that hangs in the second floor offices of the fort is probably the most accurate in this respect. Grey was the only one to depict Beanes standing with Skinner, making this the only known image of the Maryland physician in existence. A British naval officer stands at left, and a trio of Royal Marines is on guard at right.

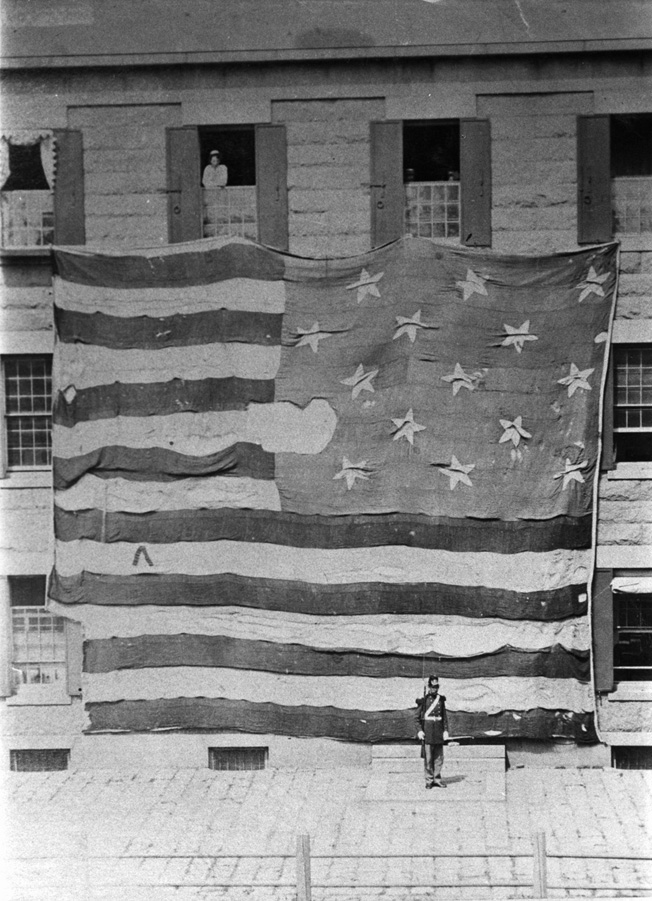

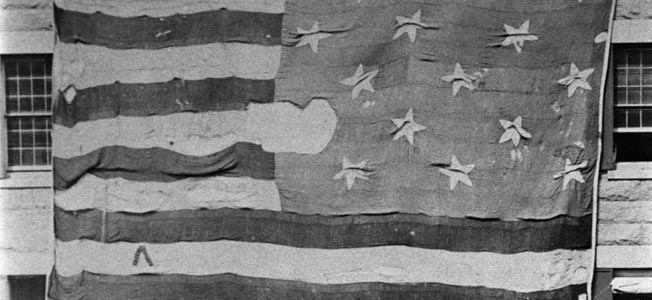

Throughout the long and dreary night, Beanes kept asking the two younger men if they could still see the fort’s American flag. Finally, “by the dawn’s early light,” Key saw “that our flag was still there,” which meant that the fort was still in American hands. But which of two known flags did the young lawyer-poet actually see? The possibility exists that he saw two flags flying at different times. The smaller storm flag most likely was the one he had seen throughout the night of the long bombardment, while the larger of the two was hoisted the next morning by Armistead’s men to herald their victory in surviving the British naval assault. It is this second and larger flag that survives today and is on public display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. No one knows what happened to the smaller flag.

The Song of a Nation

Key’s poem, originally entitled “The Defense of Fort McHenry,” was typeset by 14-year-old printer’s apprentice Samuel Sands, and first published in the Baltimore American newspaper on Sept. 17, 1814, a mere three days after the battle’s end, copied directly from the Sands handbill. It was set to the music of a popular British drinking song of the era, “To Anacreon in Heaven,” and immediately became the unofficial national anthem of the American republic.

Both the Union and the Confederacy claimed it as their own during the Civil War. After the war, the song became popular among all branches of the reunited American armed forces. In 1889, the U.S. Navy declared that it would be played at morning colors, and the Army followed suit in 1904. During World War I, President Woodrow Wilson directed that the song be played at all armed forces events, and a movement began to make it the national anthem.

Not surprisingly, the two main driving forces behind the effort for official recognition were Baltimoreans: Congressman J. Charles Linthicum and the widow Mrs. Reuben Ross Holloway, nicknamed “the Hat” because of her unusual chapeaux: tall, stovepipe creations that resembled the shakos worn by the 1814 Maryland militia. The pair finally succeeded when President Herbert Hoover signed Public Law 823 on March 3, 1931, declaring the song the national anthem of the United States. This was six years to the day from when Fort McHenry had become a National Monument and Historic Shrine, also through the efforts of Representative Linthicum.

Today, Key’s original poem manuscript is preserved in a helium-filled niche in the Enoch Pratt House wing of the Maryland Historical Society at 201 West Monument Street in downtown Baltimore, where it can still be seen, flanked by the flags of the United States and the State of Maryland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments