By Joseph M. Horodyski

During the 1920s and 1930s Great Britain built up its Far East defenses steadily if slowly, centering around Singapore as its primary naval base in the Pacific area. Money was scarce in the Depression and the armed services were forced to scrape for every penny. Eventually a first-class facility was completed, including the two largest dry docks in the Pacific outside of the American base at Pearl Harbor.

But Britain did not have enough modern ships available to station a full-time fleet thousands of miles from home, especially once the life-and-death struggle with Germany began in 1939. A few lesser ships of cruiser and destroyer size were stationed there to show the flag, with the valuable battleships and aircraft carriers kept close to home. The thinking was that in the event of war in the South Pacific, there would be time to send ships halfway around the world to meet whatever situation presented itself. Indeed, Singapore was expected to hold out alone for at least a hundred days before help could be expected. (Read more stories and historical accounts from the Pacific Theater inside WWII History magazine.)

Churchill’s Pet Project

With the occupation of French Indochina in July 1940, the Japanese were getting uncomfortably close to British possessions in the Far East and their lifeline to Australia, and rising tensions with the United States clearly indicated armed conflict was inevitable. Churchill began pressuring the Admiralty to implement a pet project of his, namely to send a squadron of three modern battleships to Malaya to act as a deterrent against Japan. It was meant to give them pause, or at the very least buy time for England to send other reinforcements and supplies so that they might have a fighting chance of meeting Japan on something like equal terms.

The Admiralty hesitated, delayed, and even ignored written pleas from the Prime Minister. The Royal Navy was by this time stretched almost to the limit, having to protect the Atlantic convoys supplying Britain and as well fielding a fleet to take on the German and Italian navies. At a meeting on October 20, 1941 Churchill once again raised the issue, at one point threatening to take some sort of action himself if his views were ignored by Admiralty officers. First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound countered by proposing to send two older, World War I-era battlecruisers, which would have been of little value anyway in a one-on-one meeting with Germany and Italy’s modern ships, and could thus be spared from Atlantic duties on what was then considered mostly a flag-waving exercise. Churchill understood this and still insisted that at least one newer battleship be sent to the Pacific. With great reluctance, Pound capitulated and a compromise was agreed upon. The Admiralty agreed to send a ship as far as South Africa to await a final decision on whether to proceed farther, depending on events taking place in the Pacific.

Already on duty in the Indian Ocean was the veteran, much-beloved battlecruiser HMS Repulse, which had actually fired her guns in anger, albeit only once, a quarter-century earlier during the Great War. Long, sleek, and graceful, her 36,000 tons were able to achieve a swift 32-knot speed at the expense of armor protection; thin-skinned, she was vulnerable to modern naval guns, though she herself boasted an impressive armament of six 15-inch guns. She was in all respects a happy ship, her crew of 69 officers and 1,240 ratings well trained and proud of the consistently high marks the ship always achieved on exercise. Commanded by Captain W.G. (Bill) Tennant, she was especially proud of her record of having steamed 30,000 miles since 1939 and not losing a single ship in any convoy she protected.

Her partner, however, enjoyed a drastically different reputation. The HMS Prince Of Wales battleship was the latest of Britain’s King George V class of battleships. She was launched only in May 1939 and barely had time to complete her trials and working-up period before being dispatched to meet the Bismarck during the latter’s famed dash into the Atlantic in May 1941. She took part in a rare battleship-versus-battleship duel along with the WWI battlecruiser HMS Hood, with some shipyard workers still aboard who did not have time to debark in the rush to put to sea. Always fighting teething troubles, she was at Hood’s side when that legendary ship was sunk in less than five minutes’ action with the powerful German battleship, suffering moderate damage herself. With turret and other mechanical troubles always plaguing her, she was forced to break off the engagement and withdraw, and was thus not in on the final action when the Royal Navy exacted its revenge three days later. With her damage kept from the public, the impression at port was that she had not had the stomach to fight and had let the Hood down.

The Ship with an Unlucky Reputation

The Prince Of Wales gained the reputation of an unlucky ship, her new, complicated design never quite living up to its potential. She was always in the yards for repair for one reason or another, and accidents of all kinds were not uncommon. After the Bismarck action she was constantly needed for sea duty, and her crew never had the time required to gel together as a unit or gain the necessary confidence in themselves and their ship.

At 35,000 tons she carried ten 15-inch guns—more powerful and accurate than Repulse’s antiquated armament—and a slightly beefed-up antiaircraft armament. With 110 officers and 1,502 men under the command of Captain John C. Leach, her one bright moment came in August 1941 when she transported Winston Churchill across the Atlantic to a meeting off Newfoundland with American President Franklin Roosevelt. It was memories of his trip aboard her and the warmth of her crew that led Churchill to choose her as the flagship around which a new Far Eastern squadron would be built, and she was ordered to join Repulse as quickly as possible.

Less than a week after First Sea Lord Pound’s meeting with Churchill, the Prince Of Wales put to sea. Chosen to command Force Z was Vice-Admiral Tom Phillips, 53, known as “Tom Thumb” because of his diminutive stature, whose last sea command had been over two decades earlier during World War I. Competent, intelligent, and well liked, he nevertheless possessed a fatal flaw: His mind was firmly rooted in the “big gun” idea of fleet action and thought in terms of battle lines and tactics dating from the prior war. A number of times in private letters or conversations with colleagues he dismissed the threat aircraft presented to ships at sea and thought it inconceivable that Japan possessed aircraft capable of sinking a modern, well-captained battleship possessing adequate antiaircraft armament and all the latest safety features. Indeed, after nearly two years of war, no battleship had yet been sunk by aircraft alone, and this reinforced his beliefs.

Some thought was given to providing air cover to this proposed Far Eastern fleet in the form of the latest straight-from-the-builder’s- yard aircraft carrier Indomitable. But during working-up exercises in the Caribbean the carrier ran aground on a reef off Jamaica and damaged her hull. No further thought was given to substituting another carrier, and Prince Of Wales sailed on alone.

Here occurred one of those incredible incidents for which no explanation was ever put forward, one that to this day remains a mystery. Prince Of Wales, with destroyer escort, arrived at Capetown, South Africa, on November 16, 1941, where she stayed for two days. At Simonstown Naval Yards, barely 30 miles from Force Z, the aircraft carrier Hennes also arrived for a refit after completing a tour of duty in the Indian Ocean. Although the smallest of the Royal Navy’s carriers, harboring but 15 aircraft, she was at present performing no vital duty in the Indian Ocean and could easily have been appointed to accompany Prince Of Wales to replace the missing Indomitable and then been refitted upon their arrival at Singapore. Surprisingly, it never occurred to anyone.

The Prince of Wales Battleship Versus the Repulse: the Birth of a Bitter Rivalry

With the naval situation in the Atlantic quiet, the Admiralty gave the go-ahead for Prince Of Wales to proceed, and she arrived at Ceylon 10 days later, joining up with Repulse. With her arrival, Prince Of Wales took over as flagship of the squadron, and both at Ceylon and in Singapore her arrival was widely reported in the local papers though, in accordance with the Admiralty’s orders, Repulse’s identity was kept secret, being referred to only as “a large warship” in an effort to keep the Japanese guessing and from learning just how weak the squadron really was. Nevertheless, the huge two ships were considered by the British to be practically invincible. They were descendants of a distinguished line of battleships stretching back nearly a century by which Britain ruled the waves and thus a world empire.

This noted, there was an instant and bitter rivalry between the two ships. Repulse’s crew resented having to serve under the command of an untried admiral in the company of such a recently commissioned and apparently unlucky battleship. With a captain who had seen two years of constant action and experience in combat and gunnery considered among the best in the Royal Navy, her crew looked forward to the coming assignment with considerably less than enthusiasm.

On December 2 Prince Of Wales, Repulse, and an accompanying squadron of four destroyers steamed up Johore Straight and entered the great naval base at Singapore, the first capital ships ever to call there. Prince Of Wales was given the best berth, with Repulse moored out in midstream like a poor relation. On arrival at Singapore Phillips was promoted to full admiral in accordance with his status as commander of the fledgling Far Eastern fleet. Phillips immediately acquainted himself with the situation and the growing crisis with Japan.

In an effort to prevent the two ships from being caught together in a surprise attack, Repulse was dispatched on a goodwill cruise to Australia while Phillips himself flew to the Philippines to meet with his American counterpart and plan a coordinated strategy to be followed upon the outbreak of war. Admiral Hart, American naval commander in the Philippines, immediately agreed to dispatch four U.S. destroyers to beef up the British fleet at Singapore. In addition, more British ships were on the way.

Japanese Strike Pearl Harbor

But events quickly overtook their planning. While in the midst of these meetings in Manila, the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor and a host of other locations throughout the Pacific. Admiral Phillips immediately returned to Singapore, arriving late on December 7. Repulse was recalled and arrived back in port that same day after an urgent high-speed run. Reconnaissance flights were dispatched in all directions to search for a Japanese convoy that intelligence had reported sailing from French Indochina and was assumed to be the nucleus of an invasion fleet heading for Malaya, only hours away.

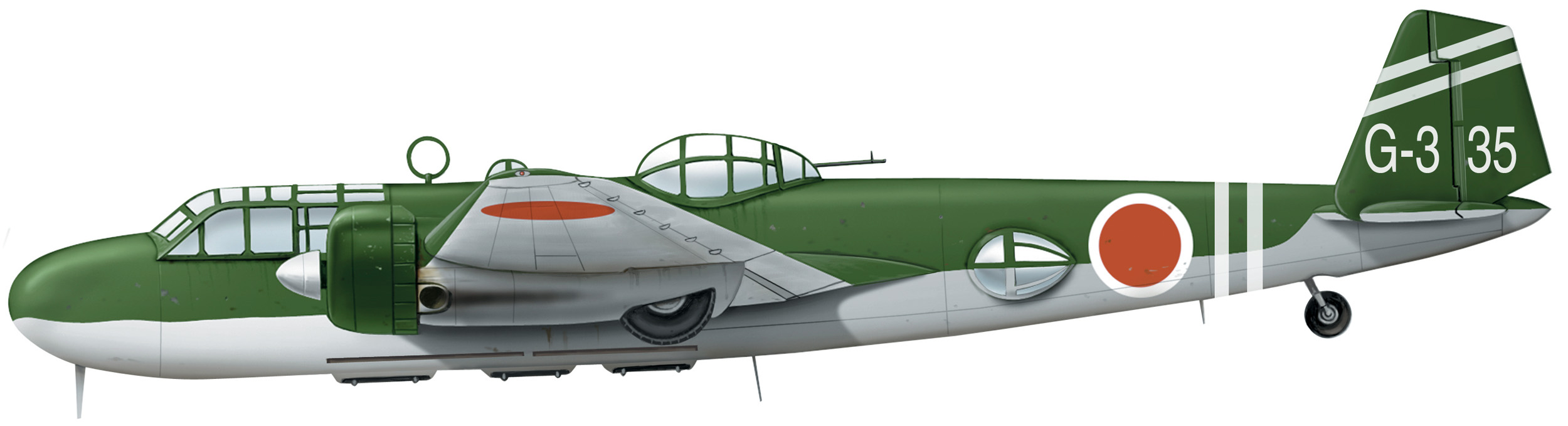

Bad weather, however, prevented any clear picture of Japanese movements. Singapore’s first-ever air raid occurred during the moonlit hours of December 8 when 17 Mitsubishi Nell bombers, flying from Indochina, raided the port and did negligible damage to the town and nearby airfield installations. The dockyard was not hit, but the antiaircraft guns of both ships joined in the defense of the city as searchlights sought out the intruders flying overhead in a neat, orderly formation. This impressed the urgency of the situation on Phillips’ mind and reinforced his desire not to get caught dockside as the American battleships had at Pearl Harbor only hours before.

Morning brought news of several Japanese landings at points along the Malaysian coast. Phillips considered his options. At midday on the 8th he convened a meeting aboard his flagship to consult with his staff and the ships’ commanders, but his mind was already made up. Every hour’s delay allowed the Japanese to consolidate their foothold in Malaya, and though his fleet was small, it could still do considerable damage if it managed to catch the Japanese invasion fleet unawares; in among the thinly armored transports, he could wreak unimaginable havoc.

“We are Going to Look for Trouble”

He ordered his fleet to slip out after dark to avoid possible Japanese spies on shore. He also arranged with the Malaysian RAF commander, Air Vice-Marshal C.W.H. Pulford, to conduct reconnaissance sweeps the following morning and to have a squadron of Buffalo fighters, designated the “Fleet Defense Squadron,” on call to provide air cover if needed. Phillips was well aware that by entering the Gulf of Siam he was placing himself within range of the considerable Japanese air forces in French Indochina, but he made a calculated gamble that there were no aircraft stationed there with the range to attack his ships and, more importantly, that there were no torpedo-carrying aircraft in the immediate vicinity. Taken in view of the previous night’s air raid, it is hard to understand how he arrived at this conclusion, so sure was he of his fleet’s supremacy. “We are going to look for trouble,” Captain Tennant announced to his men aboard the Repulse. “I expect we shall find it.”

Accompanying Force Z was a screen of four destroyers: HMS Electra, Express, Tenedos, and an Australian, HMAS Vampire. Course and speed were set so the fleet would arrive off Kota Bahru, the main invasion beaches, in the early morning hours of the 10th. There Phillips planned to make a dash among whatever Japanese shipping could be found there.

By 7:13 am Force Z had cleared the Japanese minefield off Anambas without incident, and the crews were allowed to have breakfast, the morning’s “Action Station” being relaxed to “Second Degree Readiness,” all guns loaded but only partially manned. The day wore on with clear blue skies but increasing scattered clouds, and at 1 pm Force Z passed the halfway mark to the anticipated battle area. At this time they were within 360 miles of the Japanese airfields ringing Saigon. Every hour’s steaming took them closer to the enemy aircraft stationed there, but thus far the British ships had still not been spotted. Extremely heavy cloud cover helped hide the British ships from prying eyes all day on the 9th.

It was here that luck began deserting them. Expecting the two capital ships based at Singapore to sail as soon as they received word of the landings, the Japanese had increased aerial reconnaissance and stationed two picket lines of submarines in the waters to the north of the naval base, but they had stationed them close inshore, not anticipating that the British ships might make a wide sweep out to sea on their journey north. During the morning, Force Z unknowingly passed the first of these picket lines without being spotted and had just reached the second, being on the point of eluding them, when the last submarine, stationed at the very end farthest out to sea, caught a glimpse of two ships to the east at their extreme limit of visibility. At first thought to be destroyers, it wasn’t long before I-65’s captain had correctly identified them as a King George V-class battleship and accompanying battlecruiser. The Japanese submarine then settled down to shadow them for as long as possible. Thus Force Z had nearly missed being spotted by a scant mile or two; in fact, Force Z was so far from I-65 that their destroyers were invisible to the enemy.

Within the Hour, Every Japanese Aircraft Began Converging on Force Z

I-65 immediately reported this sighting, but due to an inexplicably complicated signals organization, it was nearly four hours before the relevant Japanese commanders received the news. Ground crews worked feverishly to arm 126 aircraft—all they had not supporting ground operations—with torpedoes and bombs, while their crews were briefed on the best places to search. Four reconnaissance aircraft were immediately dispatched from Saigon and six floatplanes launched from seven Japanese cruisers in the area. The transports lying off Kota Bharu were immediately turned eastward, out of range of the impending action, so by dawn the British would find an empty harbor if they were to make it that far. By sunset the British ships sailed blindly on, still dedicated to their mission, unaware that by this time their prey had fled, making their presence now pointless, or that they had been sighted and that every Japanese ship and aircraft around was eagerly searching for them.

Soon after sunset Force Z dispatched Tenedos. Small, it was at the point beyond which it could not steam and yet still return to Singapore, and Phillips would not slow for an at-sea fueling. Unknown to the British, they had been sighted yet again, this time by a floatplane from the cruiser Kinu reporting their current course and speed, and soon the Japanese had two more confirming reports from floatplanes. By now Phillips realized he had been sighted, but still continued on his course, unsure of what action to take. Within the hour every Japanese aircraft began converging on Force Z’s reported position, at extreme danger to the Japanese themselves, because by now it was dark with four hours yet to moonrise. Four aircraft were lost during the search due to accidents. More mistakes were bound to happen, and would.

At one point a reconnaissance aircraft, piloted by Lieutenant H. Takeda, flew over the foamy wake of two large ships and immediately banked away unseen to get off a sighting report. Before long 53 bombers were racing to the position from all points, and Takeda circled over the target, awaiting their arrival. As the aircraft began positioning themselves preparatory to launching an attack, Takeda dropped a flare designed to illuminate the target for his comrades, and discovered that he was actually over the Japanese cruiser Chokai, carrying Vice-Admiral Ozawa himself, commander of the invasion fleet. Ozawa’s crew immediately spotted three aircraft lining up for attack and frantically signaled her identity to Saigon. Aware of the near-disaster, Chokai immediately veered away to the north, all aircraft were recalled, and the search was postponed until daylight.

This minor incident had enormous ramifications; neither side knew that a major nighttime naval engagement had been narrowly avoided. Vice-Admiral Ozawa’s force of six cruisers was steaming south to the latest reported position of Force Z, which was at that time steaming north on a collision course with the enemy fleet. Ozawa had no idea the British were as close as they were; Phillips also had no idea that any Japanese vessels were in the area. At 6:30, a half-hour after Tenedos’ departure, a lookout aboard Electra sighted a flare on the horizon. Startled, Phillips ordered all ships to make an emergency turn to port to pass well clear of the flare’s position, while he pondered what to do.

At this point the two converging fleets were barely five miles apart—at their respective closing speeds they would have blundered into one another in less than 10 minutes. With their superior firepower the British battleships would most likely have blown the Japanese ships out of the water and changed the course of future events. Neither side realized how close they had been to what could well have been one of the decisive sea battles of the war. The accidental actions of one lone Japanese pilot had changed the way things would turn out.

For nearly two hours Force Z sailed north while Admiral Phillips struggled with one of the most difficult decisions of his career. Knowing that his force had been sighted, he understood that all hope of surprise had been lost; still 12 hours from the invasion beaches, his prey were bound to have fled by the time they arrived. At 10:55 pm he reluctantly signaled Repulse that the operation was canceled and that they were changing course to return to Singapore. But precious time had been lost while Phillips wavered; the next 24 hours would tell whether he had delayed too long.

False Reports and Twists of Fate

Then another twist of fate. Shortly after midnight Phillips received a signal of additional Japanese landings reported near the harbor of Kuantan, 180 miles down the coast closer to Singapore. A landing there could potentially cut Malaya in two, trapping the British forces fighting in the north from those in the south. Phillips knew that his fleet would have to pass close on the return to Singapore—perhaps he could still achieve a modest victory and not return home empty-handed. He ordered an increase in speed to 25 knots and set course for Kuantan, expecting to arrive there by mid-morning.

But the report was false. It is now thought that a few cattle had strayed into a local minefield and set off a series of explosions; the jittery defenders manning the beaches during those trying days immediately had assumed they were under attack and quickly sent out calls for help. No Japanese were within two hundred miles of the area, but Phillips could not know this.

In addition, Phillips did not break radio silence to report his change of plans; indeed, since leaving Singapore nearly two days before he had maintained the strictest radio silence even though all surprise had clearly been lost and the Japanese now had a fairly good idea of where the British ships were. The only ones, it seemed, who did not know of Force Z’s whereabouts were those British forces who could have come to their aid and saved them. Indeed, no one at Singapore had any idea where Phillips was or what he was up to.

During the night Force Z was sighted yet again, this time by another Japanese submarine, I-58. The sub soon lost its quarry due to the British ships’ superior speed, but it had kept the Japanese headquarters in Saigon informed as to Force Z’s progress.

An early breakfast was served to the men just before dawn, which broke at 5 o’clock that December 10. As usual, “Full Action Stations” were manned. At 6:30 another Japanese aircraft was sighted low on the horizon as the Japanese once again picked up Force Z’s position. By this time Phillips had to know he would soon be under attack by every aircraft the Japanese could throw his way, but still he refused to break radio silence or call for air cover. Instead he proceeded steadily toward Kuantan; all eyes were eagerly scanning the horizon for the Japanese invasion fleet. At 7:18 Prince Of Wales catapulted one of its Walrus aircraft to scout the area for enemy ships; 40 minutes later Force Z was within sight of land itself, the lush, green, tropical vegetation warm and inviting. Force Z scouted for another hour, but still nothing.

Time was quickly running out. Now three hours after their morning sighting by the Japanese floatplane, Force Z turned from the area and resumed course for Singapore. Thirty minutes later Phillips’ complacency was shaken by signals that Tenedos was under attack. Having steamed on a homeward-bound course during the night, by morning Tenedos was only 125 miles from Singapore when it was sighted by Japanese aircraft looking for Force Z and immediately attacked at 10:20. Nine Japanese Nells bombed from high altitude but did not score a hit. This should have alerted the admiral that the Japanese were out and looking for him, and indeed were farther south than he anticipated, but still Phillips did nothing.

At 10:45 a large formation of aircraft was spotted approaching Force Z, the vanguard of what would eventually total 94 attacking aircraft. All guns were manned, and the antiaircraft posts were set to action stations, “First-Degree Readiness.” Fifteen minutes later the Japanese Nells were forming for attack, but Phillips retained radio silence.

A 500kg Bomb Struck the Aircraft Hanger

The initial attack force took everyone unawares by approaching from the least likely direction: the south. The planes were actually returning north after searching almost to Singapore.

The first to arrive were a flight of eight high-level Nell bombers, which flew directly over the Prince Of Wales and made for the Repulse. One 500kg bomb struck the aircraft hanger and penetrated before exploding against the armored deck just above one of the boiler rooms; damage was slight and Repulse steamed on with no loss of speed and only a trace of smoke to show she had been touched. No damage had been done to the Japanese attackers either, and Phillips here made his first tactical error. He turned his ships in unison as if controlling an outdated line of battle. This prevented half the AA guns of each ship from being able to fire effectively as targets presented themselves. But Phillips quickly realized his error and ordered independent maneuvering at the captain’s discretion from this point forward.

Ten minutes later Prince Of Wales’ radar picked up an even larger flight of aircraft approaching from the southeast. These were three squadrons of Nells—including the flight of high-level bombers that had wasted its bombs on Tenedos—accompanied by two squadrons of torpedo-carrying bombers. They planned to make simultaneous attacks on the two British ships in an effort to split their defensive gunfire, and commenced losing height to make their torpedo runs, skimming the surface of the waves at masthead height. When told by Prince Of Wales’ torpedo specialist Lt. Cmdr. R-F. Harland that it appeared to him they were lining up for a torpedo attack, Admiral Phillips, persisting in his belief that the Japanese cannot have possessed such aircraft, replied, “No they’re not, there are no torpedo aircraft about.”

But the Japanese bombers bore in and released their torpedoes at ranges from 1,500 to 600 meters. Their closing speed confounded British gunnery, whose experience had been practicing against their own lumbering Swordfish aircraft, which made their approaches at speeds of less than a hundred mph, almost half that of the Nells. The bombers dropped low, below a hundred feet, and flew through a curtain of British fire, Prince Of Wales’ sophisticated armament of 5.25-inch, dual-purpose AA guns throwing up a hail of steel “like sand being hurled all over the surface of the sea,” one Japanese pilot recalled. But many guns that day were hampered by ammunition stoppages as shells separated from their cartridges while being fed into their barrels, thus jamming the weapons. Half of the British firepower was out of action.

2,400 Tons of Water Flooded the Ship in Just Four Minutes

One Japanese Nell crashed, but the remaining eight launched their torpedoes. One hit amidships on the port side, throwing up a spray of water. The entire ship “leapt into the air and shuddered as if colliding with a solid object.” An unnatural vibration ran through the ship for some minutes afterward while Prince Of Wales amazingly took on an incredible 13-degree list and lost half her speed. Electrical power to half the ship was lost, and with it power to run lights, guns, and forced ventilation. Damage control parties were hampered by not being able to coordinate their efforts properly.

Phillips and his staff appeared “somewhat stunned.” His ship had taken on an amazing 2,400 tons of water in just the first four minutes, leaving her in a state never believed possible. Unknown until 1966 when the underwater wreck was surveyed, a second torpedo had hit immediately below the portside propeller shaft, ripping its bracket from the hull and tearing open a 12-foot hole in the bottom of the ship. The bent and distorted shaft, still being driven at full power, continued to run, causing a peculiar vibration throughout the ship until the port-side engine was shut down. But by now it was too late; the violent vibration of the shaft had torn open bulkheads and smashed oil and fuel pipes along its 240-foot length, tearing open the propeller shaft passageway and letting in a tremendous rush of water that flooded the damaged compartments above, below, and on both sides.

All this caused half the ship’s turbine, dynamo, and machinery rooms to fail from massive flooding, cutting off electrical power to lights, gun turrets, ammunition hoists, and other vital needs. Thus, within only a few moments of first being hit, the world’s most powerful battleship had lost half its primary power and three of its seven machinery rooms that supplied electricity. Three of the eight 5.25-inch magazine spaces were flooded and the ship as a whole was starting to list and settle at the stern.

Above, the attack continued, and the remaining squadron made for Repulse. At first the Japanese squadron approached and then circled away as if unsure of what to do; its commander, well aware of the mistake that had almost occurred during the night when the cruiser Chokai was nearly bombed by its own aircraft, circled around for a second approach in order to positively identify the nationality of the ship.

Satisfied, eight Nells bore in on the aged battlecruiser at the precise time another squadron of seven Nell high-level bombers appeared overhead and began dropping their bombs. But Captain Tennant, in a magnificent display of seamanship, twisted and maneuvered his ship so skillfully that he evaded every bomb and torpedo launched at him. As a result, Repulse emerged unscathed from the smoke of her own gunfire about three miles away from where the Prince Of Wales wallowed sluggishly at her reduced speed.

A Brief Reprieve From Battle

There was an uncanny quiet as the Japanese planes departed. The crews caught their breaths and checked for damage, restocking their guns and seeing to the wounded, to this point mainly from strafing by the torpedo bombers. During a lull that lasted about 20 minutes, Repulse began steaming over to where the wounded Prince Of Wales lay to see if she could be of any assistance, but the flagship ignored all calls addressed to her.

Almost inconceivably, though they had been under attack now for over an hour, Admiral Phillips still had not broken radio silence and called for air cover. It was left to Captain Tennant, on his own initiative, to broadcast the first signal to Singapore that they were under attack. Within 15 minutes of this signal being picked up, a squadron of 11 Buffalo fighters under the command of Flight-Lt. Tim Vigors took off from Sembawang airfield near Singapore nearly 150 miles away and headed to the scene of the reported battle.

But the Japanese would arrive first. By 12:20 pm the entire strength of the Kanoya Air Corps from Saigon—26 Mitsubishi Betty twin-engined bombers—was bearing down on the British ships. The crews rushed to their action stations, the Prince Of Wales barely able to defend herself. Four AA turrets could still be serviced, but with the increasing list of the ship these could not be brought to fully bear on the approaching Japanese. Aboard Repulse, Captain Tennant prepared once again to try to achieve another heroic maneuvering.

The few guns that could open fire onboard the Prince Of Wales did so, but the attacking bombers came in at differing heights and from differing angles, all aiming for the starboard side. So close did they release their torpedoes that they could hardly miss. Four torpedoes slammed into the side of the battleship. The resultant onrush of water almost counteracted the flooding from the earlier torpedo hits, but with only one of four engines still turning Prince Of Wales could barely make eight knots and was settling still deeper into the water.

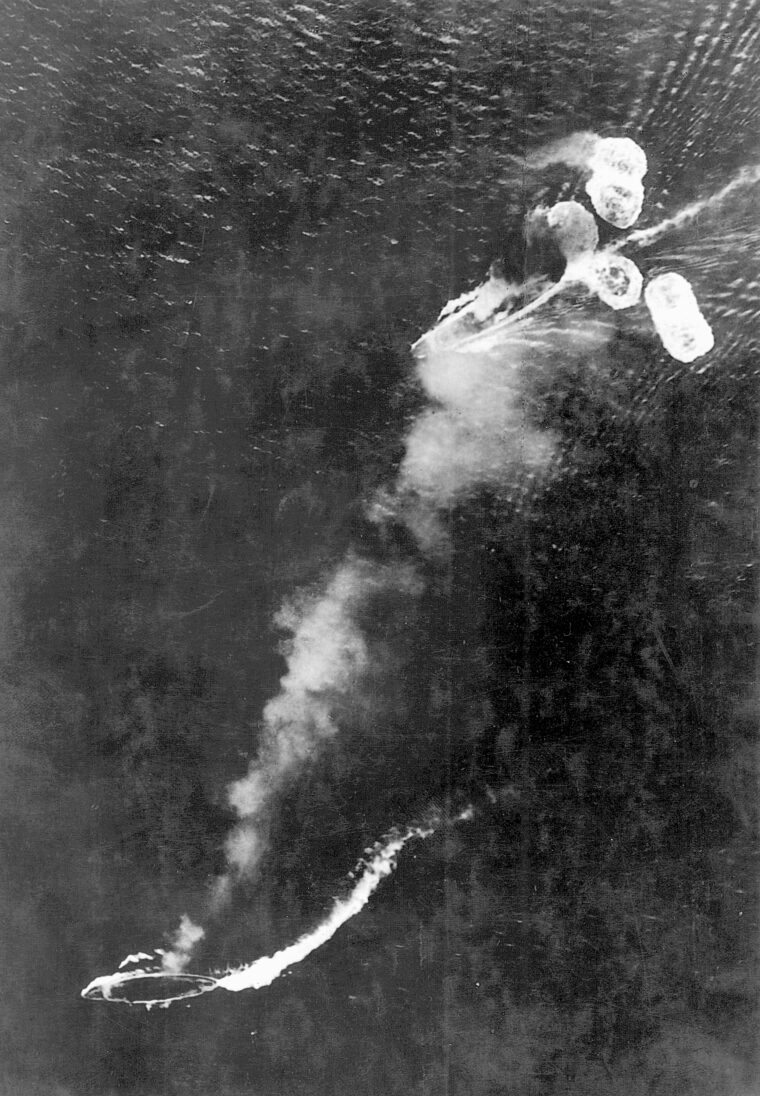

Only six of the attacking aircraft had even dropped their torpedoes; seeing that the ship was as good as finished, the remainder pressed in on Repulse, at this point still relatively intact. But her weaker 4-inch AA armament, antiquated and due to be replaced on her next refit, was simply overwhelmed by the melee. Captain Tennant’s superb skill again shone through. He managed to dodge the first eight torpedoes launched at him; by now in the two attack waves he had managed to avoid an amazing 16 torpedoes and at least eight bombs, but in a sudden sharp turn to starboard the Japanese split their attack and now bore in from both sides simultaneously. There was nothing he could do to avoid this onslaught and five torpedoes struck Repulse in quick succession, ripping open her sides to the sea, though in her anger she still managed to down two of her attackers.

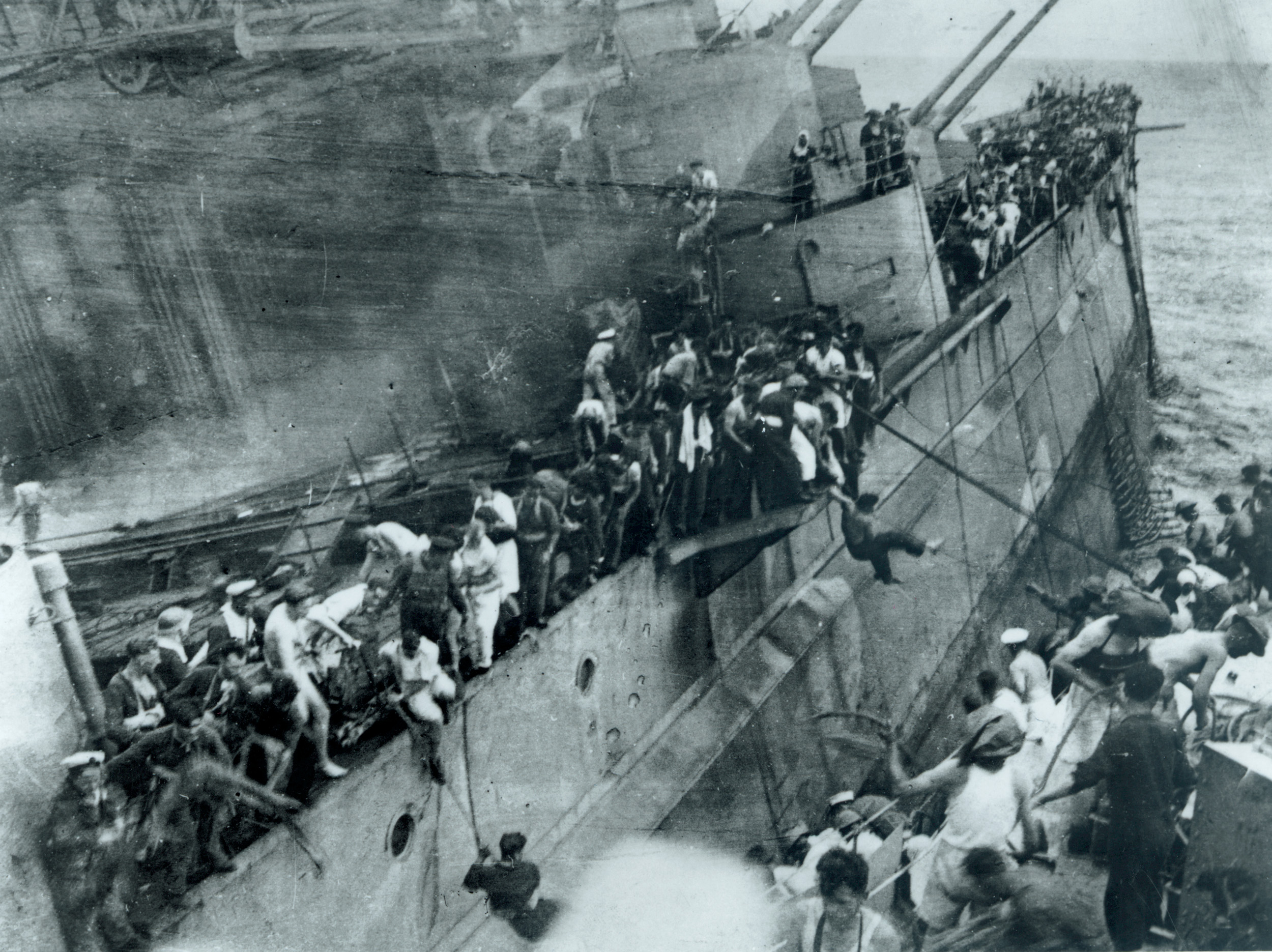

Her rudder jammed, the old battlecruiser had been grievously wounded. Her list increased to 12 degrees in two minutes and it soon became clear that she was mortally wounded. Repulse signaled that she was no longer under control and had lost all steering capability; Captain Tennant ordered all hands on deck and the lifeboats lowered, releasing his men from their duty with the words, “Good luck and God be with you.”

Two miles east Prince Of Wales was fighting her own battle; unable to steer, settling more and more by the stern with a list to port increasing. Admiral Phillips finally broke radio silence when he reported being struck by a torpedo and asked Singapore to send destroyers to assist in towing the ship to safety. Incredibly, even at this stage, he still failed to ask for air cover and persisted in the belief that his ship could still be saved.

“Abandon Ship!”

At 12:41 pm eight more high-level Nell bombers arrived, the last of the Japanese air attackers. They bore in on the hulk of Prince Of Wales but, their target barely creeping along, seven of their bombs still missed. Nonetheless, one last bomb penetrated the catapult deck, passed near the last boiler room still being manned, and burst in a large compartment known as the Cinema Flat. Actual damage to the ship was minimal but the results were horrendous; this compartment was being used as an overflow casualty station during the attacks and a rest place for men suffering from heat exhaustion. In a second the heat from the flash and bomb fragments from the explosion itself killed most of the three hundred men taking shelter there. Blood ran freely on the decks, and body parts lay everywhere.

And then it was all over. The actual attack had lasted barely five minutes; only 90 minutes had passed since the ships first went into action. As the last of the Japanese bombers disappeared over the horizon, the sudden quiet was deafening. Stunned and wounded men staggered about the ruins of their sinking ships, trying to keep their footing. At 1:15 Captain Leach of Prince Of Wales finally ordered “Abandon ship!” but the word did not make it through to all parts of the ship. Many men were trapped below decks without communication, in total darkness, or blocked by damaged passageways; many men, still at their action stations, drowned in the lower compartments. Phillips had not bothered to address the men once during the action and now did not even consider transferring his flag to another ship. Perhaps he was suffering from shock or extreme mental stress by this point. He merely sent a member of his staff to his cabin below to fetch his cap, and remained, stunned and speechless, on the bridge.

Now the accompanying destroyers came into their own, their courage and valor saving many lives that day. Electra and Vampire stood by to pick up survivors from Repulse, and Express performed magnificent work of her own. Her captain drove her right up against the side of the listing Prince Of Wales and anything that could be found—doors, boards, gangplanks of all kinds—was thrown across as bridges between the two ships so that soon a mass exodus of men began crossing over.

Some Men Were Sucked into the Gaping Torpedo-Blasted Holes

As Prince Of Wales’ list increased her keel began to drive itself up and under the bottom of the fragile destroyer, threatening to capsize them both. Lieutenant Commander Cartwright continued to wait as long as he could, knowing that every minute he stayed at extreme risk to his own ship allowed more men to cross. His timing would be critical; soon the two ships started to part and all bridges across fell away, men continuing to jump even as the gap opened. Some men who could not make it across fell and were crushed between the two hulls or drowned in the oil-soaked waters. At the last possible second Cartwright ordered “All back!” and with a grinding of metal Express backed off, her sides dented, and slid off Prince Of Wales’ hull.

Repulse was the first to sink, heeling over only 12 minutes after the last torpedo attack had started. The swiftness with which she went down meant that her crew suffered proportionately higher casualties. Those who did not escape in the first few minutes never had a chance. Most of the men who died struggling in the water waiting for rescue did so from ingesting or choking on the thick, black diesel oil that coated every part of their bodies.

Prince Of Wales’ agony went on a little longer. Her list increased to 70 degrees and then she turned turtle, some survivors walking across her flat bottom and sliding nearly 70 feet down her steel sides to the water. Some men were sucked into the gaping torpedo-blasted holes and were lost deep in the bowels of the ship; other men, oil soaked and unable to arrest their speed, slid down the sides into hundreds of struggling shipmates floundering in the water. A group of marines dived off the stern because the ship was lower there, but they were sucked to their deaths in the blades of the still- churning propellers. No one saw the last moments of either Admiral Phillips or Captain Leach; their bodies, recognized floating among the survivors, were never recovered. Prince Of Wales’ stern dipped below the waves and her bow reared up toward the sky; in these shallow waters her stern hit the muddy bottom and she began settling, disappearing beneath the waves at 1:20 pm, her death throes having lasted a full hour. Thanks to this additional time and the work of the gallant Express, more men managed to get off than were rescued from Repulse’s crew.

Bodies and debris were everywhere. Luckily for the men no sharks were seen; perhaps the chorus of explosions had killed or driven off any that might have been around. A few last Japanese reconnaissance planes flew low overhead, reporting on the demise of the two great ships to their headquarters, and flew repeated passes over the men in the water. These aircraft could have caused fearful casualties among the defenseless men in the water, but in an unusual display of restraint rarely seen during the Pacific War they did not open fire or interfere in any way with the rescue work. One pilot was seen to salute the spot where the ships went down; another story, probably apocryphal, had a Japanese pilot signaling to one of the British destroyers to cease firing and leading them to groups of survivors struggling in the water. At any rate the Japanese soon left the scene. Many had been flying since dawn that day looking for the two ships and were by now at the limits of their fuel; perhaps two dozen were badly damaged and holed by British fire.

Cursing Buffaloes

No sooner had the Japanese Mitsubishis departed over the horizon than Lieutenant Vigors’ squadron of 11 Buffaloes showed up and circled the scene of the disaster. The Japanese aircraft had had no fighter cover and had a weak defensive armament; had Phillips called for Vigor’s flight instead of maintaining radio silence until the very end, his Buffaloes could have easily broken up the attack and caused havoc among the enemy bombers. Although some torpedoes may have managed to hit home it is unlikely either ship would have been lost. But now Lieutenant Vigors could do nothing to help. His planes continued to circle overhead in case any further Japanese aircraft appeared, but for want of fuel, they were forced to break off after an hour and return to Singapore, leaving the three destroyers to go about their work. Many men cursed the planes overhead, taking out their shock and anger at the lost chances those Buffaloes represented.

Perhaps the only bit of luck to visit Force Z that day was that the three destroyers represented—barely—the minimum required to pick up all the survivors in the water. Conditions were cramped as more and more men were hauled aboard on cargo nets or Carley floats; men crowded the decks, superstructure, and any available space, many with room only to stand up. Had the attacks continued there would have been no way for these ships to even defend themselves. After 90 minutes of picking up survivors they were all dangerously top-heavy; by 3 pm both Vampire and Express left the scene of the sinking to return to Singapore, with 223 and 1,000 men aboard them, respectively. Electra stayed for another two hours, making final sweeps to look for survivors, before finally departing with over 900 survivors aboard. Captain Tennant of Repulse survived the sinking and was one of the last to be picked up.

The three ships all arrived back in Singapore around midnight. The next day, the heavy cruiser Exeter, the start of Phillips’ promised reinforcements that he had refused to wait for, arrived in Singapore. With the loss of the American Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor three days before, this lone British cruiser now represented the only capital ship in the entire Pacific left to face the might of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Word reached Churchill in London even as Force Z’s survivors were disembarking on the quays of Singapore. At first refusing to believe the news, Churchill later wrote in his memoirs that he “turned over and twisted in bed as the full horror of the news sank in on me.” Never before had Britain lost two battleships in a single day; it was Churchill himself who insisted on their being sent to Singapore, now clearly like “lambs to the slaughter.” “I was thankful to be alone. In all the war I never received a more direct shock. Over all this vast expanse of waters Japan was supreme, and we were everywhere weak and naked.”

An investigation was later conducted, but full details about why the two ships had been lost so quickly had to await the end of the war, allowing Japanese records to be examined and a proper survey of the wrecks made. No one was ever held accountable for the disaster; no blame was ever apportioned.

Solving the Mystery

The morning following the sinkings, a lone Japanese Nell again flew over the spot where so many men had perished only hours before and dropped a wreath, a tribute to the bravery of those who died, on both sides. It was an act of chivalry rarely seen in the Pacific War. In the next two years the Japanese located the wrecks and even considered for a short time salvaging them, but it was beyond their means.

So what, exactly, had happened? History had never before seen anything like it. In barely 90 minutes the centuries-old reign of the battleship had come to an end. Never before had there been such a one-sided battle: two capital ships lost, taking over 840 men with them, for the loss of only four Japanese aircraft. No one believed it could ever happen, and the shock to the British psyche was thus even greater than that caused to the Americans by the Pearl Harbor attack. The Americans could at least rationalize that their fleet had been caught in port, trapped and unprepared, rather than on the high seas in open combat. Still, after Prince Of Wales and Repulse, Britain never again lost a battleship.

Today both ships rest on the bottom, considered a war grave of 840 men by the British government. Repulse lies in shallower water at only 180 feet; the Prince Of Wales battleship two and a half miles away 216, feet down. Both ships can be seen from the air under favorable conditions.

Of the four destroyers that accompanied Force Z on its final sortie, three were sunk in the coming weeks during the Japanese campaign in Malaya; only the gallant Express survived the war, being transferred to the Canadian Navy in 1943.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments