By Michael D. Hull

When German panzer and infantry columns rumbled across the frontier into Russia on June 22, 1941, the Soviet Air Force was woefully unready for war.

Marshal Josef Stalin had decided to revamp military aviation. Like the Red Army, whose officer corps he had brutally purged in the 1930s, Soviet air power was undergoing a transition and was in a sorry state. During the first disastrous week of Operation Barbarossa, the Nazi invaders destroyed more than 4,000 out of 7,700 Russian airplanes.

The Russians flew aging bombers on suicidal raids against the Wehrmacht. Of the 800 in service, only 266 were still flying by December 1941. Faster and more maneuverable Messerschmitts shot down Soviet fighters almost at will and inexperienced Russian pilots resorted to such desperate tactics as trying to ram the German planes.

Stalin Calls on Marina Raskova to Recruit Female Pilots

After suffering catastrophic losses in men and planes during the German push into the Ukraine that summer, the Soviet high command was forced to call on one of the country’s most experienced women fliers, Marina Raskova, the “Russian Amelia Earhart,” to organize three regiments of female pilots. From the civil air fleet and flying clubs that had been formed across Russia in the 1930s, the beautiful, soft-spoken Major Raskova selected 200 recruits aged between 18 and 22.

In October 1941, she began to form the 586th Fighter Regiment, the 587th Bomber Regiment and the 588th Night Bomber Regiment. The latter would later earn the coveted designation of 46th Guards Night Bomber Regiment. As well as fighting in all-female units, other female pilots also flew with male squadrons. Women’s air regiments served in the Ukraine, the northern Caucasus, the Taman Peninsula, the Crimea, at Stalingrad and even over Berlin, bombing German supply trains, railroad junctions and ammunition dumps along the way. The 586th Fighter Regiment fought in 125 aerial battles in two and a half years.

These female pilots displayed incredible courage and stamina that rapidly won the admiration of their skeptical male superiors. For their aggressive spirit under adverse conditions and often against superior odds on the Eastern Front, the Germans dubbed them “Night Witches.” They were the only women to fly in combat in World War II.

The 254 young women of the 588th Night Bomber Regiment were chosen to make nightly attacks on the well-defended German line north of the Crimea. Flying through the bitter Russian winter in the open cockpits of slow, aging, wood-and-canvas Polikarpov PO-2 biplanes that could carry only four bombs, the women averaged 15 to 18 round trips a night through intense enemy antiaircraft fire. Backed by skilled mechanics and bomb loaders, most of whom were also women, the crews of the 588th completed 24,000 sorties during the war and dropped 23,000 tons of bombs.

It was a brutal air war. One night, the Germans shot down four PO-2s, killing eight women in 15 minutes. On another night, two women fliers were downed behind enemy lines. They managed, over the course of three days to walk back to their unit, dodging German patrols along the way.

The Night Witches, who bore lyrical names like Tamara, Katya, Polina, Valentina, Shenya, Nina, Alexandra, Galina and Katerina, carried wild flowers in their cockpits as a statement of their femininity amidst all the death and suffering. They never hesitated to plunge into German formations, no matter what the odds. On one occasion, two Yak fighters of the 586th Regiment intercepted 42 enemy bombers on their way to hit a rail junction. The two women attacked immediately, shooting down four bombers before their own planes were crippled.

The German air crews were incredulous when they discovered that many of the Soviet pilots attacking them were women. In June 1943, a group of Messerschmitts was flying cover over German artillery positions in the Caucasian foothills. Suddenly, the Luftwaffe fliers saw nine Soviet dive bombers approaching, flanked by a fighter wing. As the Germans peeled off to attack, they were amazed to hear female voices calling to one another on their radios. The hapless Germans were drawn into a crossfire and in seconds four Messerschmitts went down.

Marina Raskova was killed in action in 1943. In the first state funeral conducted in Russia since the beginning of the war, her ashes were placed in the Kremlin wall with full honors.

The Most Famous Night Witch

Most famous of the Night Witches was Lilya Litvak, a shapely, five-foot-tall blonde with gray eyes and a sunny personality. She flew with both the 586th Fighter Regiment and the mostly male 73rd Fighter Regiment, becoming the leading woman ace by destroying 12 German planes. Her prowess in the cockpits of Yak-1 and Yak-9 fighters earned her the nicknames of the “Free Hunter” and the “Rose of Stalingrad.”

Lilya (variously Liliia and Lydia) was one of hundreds of young women from flying clubs who answered their country’s desperate call in the autumn of 1941. Leningrad was surrounded, the German armies were approaching Moscow and more than three million Russians had been taken prisoner. There was no time to be lost.

Lilya grew up in a modest but happy home near the subway station at Nova Slobodskaya Street in Moscow. Her father was a railroad worker and her mother worked in a store. Becoming fascinated with aviation while a teenager, Lilya read every book she could get her hands on about aircraft design, navigation, aerobatics, and meteorology. At the age of 16, she persuaded the chief instructor at a Moscow flying club to start training her. She quickly proved that she had natural talent and was a fast learner.

Lilya soloed in a PO-2 biplane after only four hours’ instruction and soon became a flying tutor. She knew that her parents would be horrified if they knew she was going up in airplanes, so she smuggled her instruction books into her home and told her mother and father that she was attending a school dramatic society in the early evenings. By the time her secret was discovered she was an able pilot.

The girl was both capable and popular. Larissa Rasanova, a fellow instructor, said, “Lily was one of these people who was good at everything she tried. And she was so popular with the boys. I think every man at the flying club was in love with her.”

The Engels Training Base for Female Fliers

In October 1941, Lilya was one of a thousand young women, most of them hardly out of their teens, riding eastward on trains toward a training base at Engels, a small Volga River town a few hundred miles north of Stalingrad. At the former peacetime airfield that was being rapidly transformed into a well defended air base, Lilya and her comrades would become pilots, navigators, gunners, radio operators and ground crew members. The seven months’ training was scheduled to commence on October 15.

The recruits were housed in an old school building on the airfield perimeter. They pinned snapshots of their boyfriends and families on the bare walls behind their hard wooden bunks and, with scissors, needles and thread, worked to make their bulky, woolen vests, tunics, and baggy trousers into more attractive uniforms. Lilya drew a belt tightly around her tiny waist that emphasized her hourglass figure and added a flower to her cap. The women, many of whom would serve together for four years, were helpful to each other and there was a minimum of jealousy.

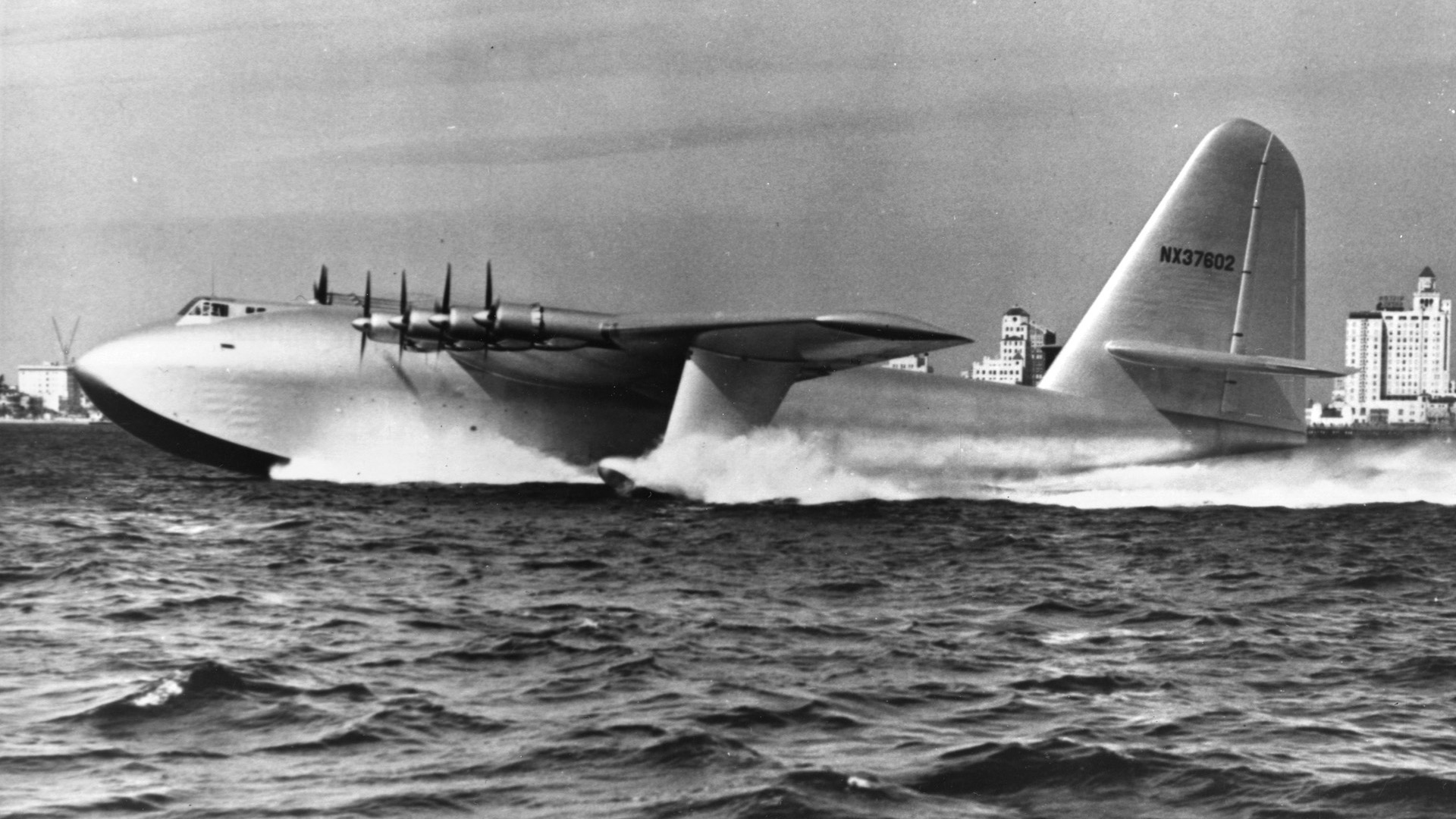

Because the Soviet Union desperately needed frontline fliers, the training schedule at Engels was hard and intense. On some days, the girls spent as many as 14 hours in the classroom and in the air. Courses that would have lasted for up to two years in peacetime were compressed into six months. The women practiced bombing from varying altitudes on ranges near the airfield and learned the theory of dogfighting. They used the PO-2 biplane, an outdated 1927 design which was both small and slow. Its five-cylinder engine was capable of only 60 miles an hour. It was such a primitive plane that when bombing, the pilot would tug on a wire in the cockpit to release the little bombs carried in racks beneath the wings.

The PO-2 was a workhorse. Besides serving as a primary trainer and night bomber, it was used as a scout plane, an aerial ambulance and a small transport for carrying couriers and important prisoners. Because of its wood and canvas construction the PO-2, which resembled the Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber of British Fleet Air Arm fame, was able to escape detection by German radar. PO-2 raids inflicted more psychological than physical damage on the enemy, who nicknamed it the “Duty Sergeant” because of the many sleepless nights it caused.

Lilya Litvak and her comrades practiced night flying with instructors and then on their own. They learned to navigate with stopwatches and crude, manual computers strapped to their knees and without benefit of radio communication. Their return to the airfield after training flights was often more a matter of luck than judgment, but there were no fatalities.

All of the women chosen for pilot training wanted to fly fighters and none were more determined than Lilya, who had grown disenchanted with the decrepit PO-2. She spotted a squadron of trim, long-nosed Yak-1 single-seat fighters parked at the Engels air base and determined that one of them would be hers. She wanted to tangle with the Luftwaffe.

The time came for the women to graduate from the PO-2 and start training in the planes they would fly into combat. Fliers assigned to the bomber regiments now learned to fly either converted PO-2s or twin-engine Petylakov PE-2 light bombers. Lilya and the others chosen to fly fighters finally got their Yak-1s. They eagerly practiced taxiing, circuits, mock dogfights, and flying in pairs, which was a standard maneuver in Red Air Force fighter groups.

Rugged, easy to fly and mounting wing machine guns and a cannon in the propeller shaft, the Yak was based on the British Supermarine Spitfire and the Messerschmitt 109. Designer Aleksandr Yakovlev tirelessly improved on the basic Yak-1. The Yak-3 could outfly the best enemy fighters and German pilots were instructed to avoid it. The Soviet Union eventually built more than 30,000 Yaks some 58 percent of its wartime fighters.

Lilya and the other women mastered the Yak-1 and itched to get into action. Their training finally ended and a big party in the Engels schoolhouse on May 17, 1942, marked their graduation. Accordions and banjos played, vodka flowed freely, candles flickered on tables and window ledges and the happy young women danced with their instructors.

The 586th Fighter Regiment Gets Sent to the Front

At inspection the next morning, Major Raskova announced that the 586th Fighter Regiment was going to the front. The girls cheered wildly and hugged each other. Their Yaks were ferried in that day. Chattering excitedly, Lilya and her comrades drew automatic pistols from the armory, donned leather flying helmets and walked to the line of waiting fighters. In formations of four, they took off and swept westward across the wide Volga to their assigned base at Saratov, testing their guns on the way.

The women’s regiment was assigned to defend Saratov, the site of munitions plants and railroads. After touching down, the fliers unpacked their belongings in the barracks, sipped tea and wrote letters home. They were now on the front line and some members of the regiment received their baptism of fire on their second night at Saratov. A squadron took off to intercept German bombers and one of the Russian girls, Galia Boordina, boldly dived into the enemy formation and forced it to turn away.

Day after day, the women of the 586th Regiment flew sorties and became combat veterans. It was a hard life and the strain began to show on the girls. Their hair was now tousled and their eyes red-rimmed and they flopped exhaustedly on their bunks after missions. They downed German planes and harassed the bomber formations, yet they were still a questionable factor in the minds of many senior Red Air Force officers. They still had to prove themselves.

By the autumn of 1942, the regiment had been transferred to an airfield near Voronezh, a major road and rail junction that controlled crossings to the River Don. The town was a key point in the German summer offensive in the south. Growing to hate their foes for the suffering and devastation they had wrought on their country, Lilya and her comrades drove off numerous bomber formations around Voronezh and skirmished with the escorting Me-109s. The regiment did not down any German fighters, but it also lost no pilots. The value of the women fliers was beginning to be noticed by the Soviet high command.

On to Stalingrad

That September, Lilya and her best friend, Katya Budanova, were informed that they were being transferred to the all-male 73rd Fighter Regiment at Stalingrad, where one of the most desperate and decisive battles of World War II was being waged. The sprawling city on the Volga was a burning, smoking, rubble strewn hellhole, hammered day and night by German bombers, dive bombers and fighters. The enemy had aerial superiority, yet the invaders had bitten off more than they could chew and the tide of war was turning slowly in the Russians’ favor.

Lilya was thrilled at the new assignment and yearned for the chance of single combat with the hated Huns. She packed her few belongings, socks, gloves, a woolen helmet, a tin mug, a silk handkerchief and her diary, into a rucksack and sat down to write a letter to her mother. “Dearest Memenka,” she wrote, “I am writing this sitting in the cockpit on readiness. I’m thinking of sitting with you in our dear home. I’m eating my favorite fritters in my dreams … .” Lilya asked her mother to send some warm gloves and socks, toothpaste and a photograph of her father.

Then, late on a September afternoon in 1942, she clambered into her Yak and flew southeastward to Stalingrad. After an hour’s flight, she touched down at one of the new airfields the city’s defenders had hurriedly constructed on the far side of the Volga. Stepping down from her plane, Lilya listened to the rumble and clatter of artillery and small arms across the river. There was smoke in the air.

In the briefing room of the underground operations center, Lilya warmed herself in front of an old potbellied stove while pilots of the 73rd Fighter Regiment were being debriefed after a sortie. Eventually, the men realized that there was an attractive young woman in their midst. “Hello, I’m Lieutenant Lily Litvak,” she said gaily, standing up and straightening her tunic. “I’m your new pilot.”

Lilya’s New Enemy: Male Chauvinism

Lilya and her friend, Katya Budanova, who flew in the following morning, soon found out that they had another foe to contend with besides the Germans: male chauvinism. Their new comrades and their officers did not relish the idea of having women fly with them. The regimental commander, Colonel Nikolai Baranov, had lost many friends and good pilots and told Lilya and Katya that he was not prepared to risk the lives of his “free hunters”—pairs of fighter pilots—by sending up girls. Baranov, a distinguished combat veteran, admitted that the Night Witches had acquitted themselves bravely in defending Saratov, but feared that Lilya and Katya would not be equal to the merciless air war raging over Stalingrad.

Lilya was dejected, but she did not give up. She would prove to Baranov that she and Katya were ready and she planned to work feminine wiles on him if it became necessary. The two fliers and Ina Pasportnikova, Lily’s mechanic, were quartered in a house on the airfield perimeter, well away from the men’s huts. A sentry was posted to “protect the girls from the Germans.” As they strolled across the field to their quarters, the women passed the fighters. Lilya’s Yak was parked next to Katya’s plane and they were being refueled and their guns loaded. Lilya’s aircraft bore a distinctive “No. 3” painted on the fuselage. She called it her “Troika” (three). She longed to climb in and take off.

Troika was flown into combat anyway and all Lilya could do was wait and watch with relief when it returned safely. One young male pilot refused to fly it because a female mechanic, Ina, had worked on it. The irrepressible Lilya refused to let the men’s attitudes and the inaction upset her and she made friends with some of the pilots. Soon, her admirers included Captain Alexei Salomaten, a close friend of Colonel Baranov, and Boris Gubanov, a tall Georgian who loved her from afar.

Lilya decided to confront Baranov, who had insisted, “I will not have girls flying with me.” She walked to the command bunker and begged him to let her and Katya join his free hunters. When Baranov threatened to transfer Lilya and Katya back to the 586th Women’s Fighter Regiment, the Moscow girl, who felt she had nothing to lose, responded, “We want to fly with you, and I’m sitting here until you tell me we can.” Salomaten, who had entered the bunker, intervened. Winking at Lilya, he told Baranov, “But surely, Kolya, you understand. She’s a pilot. She must be given the chance to fly with us.”

He clapped his friend on the shoulder and Baranov was beaten. “Okay, Alexei,” the colonel said, “tomorrow morning, Lieutenant Litvak flies as your wingman. But, by God, she’d better be good!” Baranov also agreed to Lilya’s appeal on behalf of Katya. He grinned and said that she could be his wingman the next day. Baranov was not yet convinced, but Lilya had won a round. She sighed with relief and tingled with expectation.

Finally, A Chance to Fight

On a fine September day, Alexei put Lilya through her paces in the air, after which the girl confided to Ina that she and Alexei had fallen in love. On the next day, he told Lilya, she would get a chance to shoot down Germans flying one of the new Yak-9 fighters. With a top speed of 370 miles an hour, a fast climbing capability and mounting a 37mm cannon and a pair of 12.7mm machine guns, the Yak-9 was almost the equal of the German Focke-Wulf 190.

After an early morning briefing, Alexei and Lilya buckled on their sidearms, picked up maps and parachutes and walked to their planes. Alexei squeezed Lilya’s arm and winked at her. She climbed into her cockpit and Ina helped her to buckle on her parachute. “She was bursting with good humor and excitement,” Ina recalled later. “She was like a beautiful little animal, straining at the leash.” Alexei and Lilya then zoomed into the sky to patrol the western approaches to Stalingrad.

At 10,000 feet, they hid in clouds to hunt for their prey. Then Alexei radioed, “Follow me.” They dived into a formation of Heinkel 111 bombers and Alexei damaged the leading plane. Lilya pressed her gun button and swung away to avoid hitting the Heinkel’s tailplane, but had lost sight of Alexei. So she rolled back in the direction of the German formation, which was scattering, with the leader diving out of control.

Suddenly, Lilya heard Alexei’s voice crackle in her headphones: “Troika, Troika, behind you! Break right!” A Messerschmitt 109 was on her tail, lurching in her slipstream and firing. Lilya felt bullets hammering behind her cockpit, so she swung hard right, dived and rolled. The German followed, but the girl felt no more hits. Then the Me-109 erupted in a ball of orange flame; her wingman had finished him off. Only a minute had elapsed since their dive through the enemy formation. Now, the German planes had gone.

Plunging through broken clouds, the two free hunters spotted another prey, a Heinkel 111 straggler. Alexei dropped behind and ordered Lilya to attack. Easing her Yak up under the bomber’s tail and rocking in its slipstream, she loosed shells into its underbelly. Flames engulfed the German plane, and it dived into a field. It was almost like target practice and Lilya felt sickened. She and Alexei returned to base with victory rolls, and a grinning Colonel Baranov watched. Jumping down from his plane, Alexei put his arm around Lilya and declared, “This girl’s going to be an ace—I’ll bet you anything on that!”

The Tide Shifts and Lilya Becomes Famous

The days shortened and grew colder as the winter of 1942-43 arrived. By Christmas, Lilya had shot down six planes, three fighters and three transports, as the bitter Stalingrad campaign wore on. By now, the Soviet ground troops and airmen were struggling to prevent General Friedrich Paulus’s trapped German Sixth Army from being supplied by air. Alexei and Lilya flew together on days when the weather permitted and in the evenings they held hands and strolled around the airfield. Their love grew.

The Russian fliers gained superiority in the skies over embattled Stalingrad, and news of the Night Witches’ exploits spread. Lilya’s name appeared in several newspapers, but she was shy and shunned publicity. She refused to speak to a visiting correspondent and told him to interview her mechanic. Yet, there was a touch of flamboyance in her. She asked one of the airfield mechanics to paint a large white rose on each side of her Yak’s fuselage and a smaller row of roses along the nose to signify her aerial victories. So Lilya Litvak became known as the “White Rose of Stalingrad.” She was also now known to the Germans and on many occasions ground monitors heard enemy pilots warning each other: “Achtung, Litvak!”

The horror of the air war was rudely brought home to Lilya one day when Boris Gubanov was killed. During an encounter with a formation of Junkers bombers, his Yak was set afire. Gubanov’s radio transmitter was switched on as he tried to eject himself and Lilya and Alexei listened to his screams as he burned to death while ramming one of the enemy bombers. Lilya was shaken and felt guilty that she had not been kinder to him.

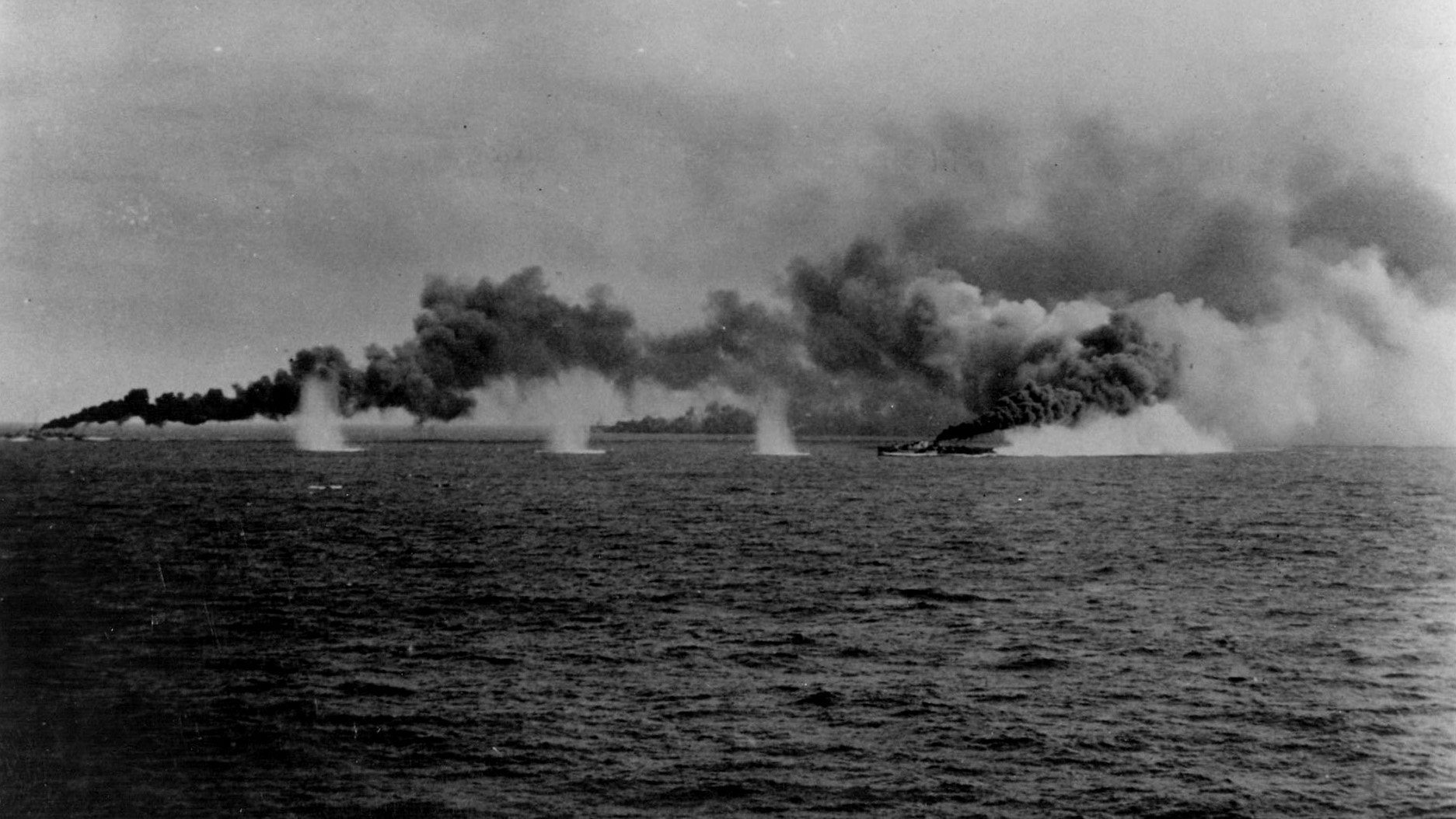

In the air and on the ground, the stubborn Soviet soldiers, airmen and civilians were gaining the upper hand in and around Stalingrad, now a wasteland of blackened rubble. Russian infantry, artillery, and armored units mauled the Sixth Army, which was running low on ammunition, rations and medical supplies. The Red Air Force was gaining strength as production plants turned out thousands of aircraft and hundreds of British and American fighters were ferried to Russia. By the middle of 1943, the Red Air Force would boast 8,300 frontline planes and half a million men and women.

Germans died by the thousands in the bitter winter and the Russians checked efforts to relieve Paulus’s desperate army. In January 1943, he and more than 94,000 of his men surrendered. An estimated 147,000 Germans had been killed in Stalingrad and a further 100,000 around the city. It was a great turning point and the Germans were now forced to retreat.

Lilya’s Luck Runs Out

That March, the 73rd Fighter Regiment was shifted to an airfield at Rostov in the Don Basin, where the German forces had been regrouping after their retreat from the North Caucasus. Lilya had now been flying in combat for 10 months. She was a fine pilot and an aggressive warrior and had been very fortunate. However, her luck was about to run out.

One day, with Alexei as her wingman, she closed in to attack a Heinkel 111 bomber. She damaged the enemy plane, but a sustained burst from its gunner smashed her Yak’s engine cowling. The engine died and Lilya frantically pulled away as the German crew bailed out of the crippled bomber. She had downed her ninth enemy plane, but she was in trouble.

As Alexei guided the girl to a long pasture for a forced landing, Lilya felt terrible pain in her left leg. The bullets that had knocked out her engine had also hit her leg, but she did not tell Alexei because she did not want to worry him. Struggling to stay conscious, Lilya slammed into the pasture with her undercarriage still folded up. The Yak hit a rut, spun around and jerked to a halt. With blood flowing from her leg, Lilya staggered to a nearby roadside as her lover circled the pasture and radioed the base for help.

Lilya used her scarf to tie a tourniquet around her thigh. She waved to Alexei, who was running low on fuel and had to make for base. When Colonel Baranov drove along a few minutes later to pick her up, Lilya passed out. In a field hospital, a surgeon removed the bullet from Lilya’s leg and gave it to her as a souvenir. Alexei gave her two gifts, a dagger with a wooden handle that he had carved himself and a volume of poems in which he had written: “To my love, Lily.”

Recuperation, then a Return to Action

When she had recovered, Lilya was sent on convalescent leave to Moscow. She hated to leave Alexei and the fighter regiment, but she was overjoyed at being reunited with her mother and 14-year-old brother, Yuri. Her father was away driving a train near one of the war fronts. Despite a severe food shortage in Moscow, Lilya’s mother cooked some of her favorite meals. The girl’s leg mended slowly and she was able to walk short distances without a cane. She found it hard to relax however, and after being home less than two weeks she decided to return to Rostov.

On her last night in Moscow, Lilya donned a pretty blue and white dress and went with her mother and Yuri to the Bolshoi Theater, where Ulanova was playing Odette in Tchaikovsky’s ballet, Swan Lake. As a wounded veteran, Lilya had been able to secure tickets. After a tearful farewell early the next morning, the brave little flier limped off to hitch a plane ride back to Rostov. She would not see her family again.

Arriving back at the Rostov airfield, Lilya was shocked to learn that Colonel Baranov had been killed. Anxious to fly again, she volunteered for a hazardous mission against a well defended German observation balloon that had been calling down accurate artillery fire on Russian troops in the sector. One Soviet plane had already been downed while attempting to destroy the balloon.

Lilya studied her maps, limped out to her Yak-9 and took off. Flying at 200 feet across the enemy lines she ignored ground fire and hits on her fuselage before dropping to 100 feet. With the late afternoon sun behind her, she approached the balloon, which was being winched down for the night. At a range of 500 yards, she sent a stream of cannon and machine-gun fire into the belly of the balloon and watched it disintegrate in a brilliant orange flash. Exultantly, she zoomed home and flew inverted victory rolls across the field at a height of 50 feet. She had not lost her touch.

Losing Alexi

One afternoon during a lull in the fighting, Lilya, Katya and some other pilots lounged on the grass and watched Alexei teach dogfighting tactics to a squadron newcomer. As the two Yak fighters twisted and chased each other at dangerously low levels, Alexei turned steeply which caused him to lose height. His wing dropped and the plane hit the ground with a loud crash. Everyone ran frantically across the field. The impact of the crash had shoved the front end of Alexei’s plane into its fuselage, crushing the cockpit.

When Alexei was finally pulled from the wreckage, he was virtually unmarked, but his body had been compressed into a fraction of its normal size. Anguished, Lilya buried her face in Ina’s breast before kneeling beside her lover’s body and lightly kissing his cold forehead. Then she wept.

Lilya grieved for months. She did not talk much about Alexei, but she carried a snapshot of him everywhere. The tragedy imparted to her a renewed dedication and her mechanic observed that she “had become almost obsessive in her hatred.” Lilya’s 10th aerial victory was over a Luftwaffe ace. She dueled with him like a madwoman for 15 minutes before sending his Messerschmitt down in flames.

The aggressive spirit and skill of the free hunters, both male and female, was now legendary in the skies over the Eastern Front. Near Orel in 1943, Major D.B. Meyer of the Luftwaffe reported that his unit was battling “brave daredevils, well trained and excellent fliers, with a sure flair for German weaknesses.” although Russian aerial superiority had increased, the free hunters still found themselves outnumbered as they waded into the enemy formations. Lilya was shot down twice in three weeks and then was forced to make an emergency landing. The next day, the Rose of Stalingrad was aloft again, in a replacement fighter.

During a dogfight her Yak was set afire. Lilya swung the plane upside down and threw herself from the cockpit at a low altitude. Her parachute opened just in time, but she was badly shaken. Continuous combat and the deaths of many friends were taking a toll on her. She was just as determined, but she was not the same lighthearted girl who had left Moscow.

She wrote to her mother, “Battle life has swallowed me completely. I can’t seem to think of anything but the fighting … I love my country and you, my dearest mother, more than anything. I’m burning to chase the Germans from our country so that we can live a happy, normal life together again.” She had to dictate her letter because her right hand had been injured by a bullet.

Lilya was comforted by her friend and fellow free hunter, Katya Budanova, a boyish looking young woman who had nine German planes to her credit. Katya loved to sing and was singing on the morning of July 18, 1943, when she took off on her last sortie. After a tangle with several Focke-Wulf 190s she was forced to make an emergency landing. Her plane blew up, and when villagers pulled her from the wreckage, Katya was dead.

Lilya was again devastated. She had lost Alexei, Boris Gubanov, Colonel Baranov and now Katya. She felt almost alone now, but she steeled herself and carried on. The war raged on and there were still plenty of Germans to be hunted down.

The White Rose Disappears

Around sunrise on Sunday, August 1, 1943, Lilya strolled across the airfield near the town of Krasny Luch in the Donets Basin. She paused to pick a posy of wild flowers and chatted with Ina, her faithful mechanic, who had readied Lilya’s Yak for the first sortie of the day. Lilya hoisted herself into the cockpit and pinned the flowers beside the instrument panel. She felt better than she had for some time. She waved goodbye to Ina, gunned her engine and took off.

Ten miles from the front line, Lilya and five fellow free hunters spotted their quarry, a large formation of Junkers 88 bombers escorted by Me-109s. The Russians approached the enemy, but Lilya did not see the German fighters, two of which pounced on her. She turned to confront them and she and the Germans disappeared into a cloud. Then, Ivan Borisenko, Lilya’s wingman, was horrified to see smoke trailing from the Yak bearing the white rose. He reported later that eight Me-109s had borne in on Lilya. The odds were too much even for her.

The White Rose disappeared over enemy territory. No one saw her crash, but there was no doubt that she was dead. Ina said, “When we realized Lily wasn’t coming back, men in the regiment broke down and cried. They never found her aircraft or her body, so there was no funeral.” Borisenko said, “Everyone without exception loved her. As a pilot and as a person, she was beautiful.”

Lilya, who was listed as “missing without a trace,” had been recommended for the Hero of the Soviet Union medal, but regulations decreed that it could not be awarded to anyone who had disappeared in combat. Eventually, in 1979 the body of a woman pilot buried in the village of Dmitrievka was discovered and it was determined to be that of Lilya. Her records were amended to “killed in action” and Soviet Chairman Mikhail Gorbachev signed the Hero of the Soviet Union citation in May 1990. It was presented to Lilya’s brother, Yuri.

The first woman in history to shoot down an enemy aircraft, Lilya Litvak completed 268 sorties and was the top scoring female fighter pilot. Her 12 aerial victories, plus three shared kills, were notched in less than a year of combat flying. A memorial, topped by a heroic bust, was erected to her in Krasny Luch.

Michael D. Hull is a frequent contributor to WWII History and a contributor to the World War II Desk Reference with the Eisenhower Center for American Studies. He resides in Enfield, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments