By Flint Whitlock

The mission was top secret. The heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35) had just delivered the last parts of the atomic bomb from California to the island of Tinian and was heading, unescorted, to Guam when it was intercepted by a Japanese submarine, the I-58, and torpedoed on July 30, 1945.

The Indy sank within 12 minutes. Out of 1,197 men aboard her, about 900 either jumped or were blown overboard. Over the next four-and-a-half days, a combination of hypothermia, dehydration, lack of food and water, and attacks by sharks depleted this number to just 316 men, who survived to be miraculously rescued.

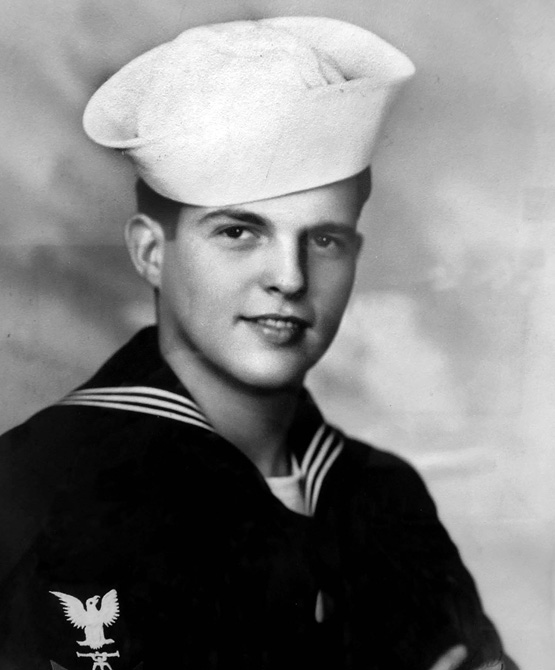

Twenty-one-year-old Paul J. Murphy was born in Chillicothe, Missouri, in 1924 and graduated from high school in 1943; two weeks later he was drafted. He was one of those 316 who survived one of the worst disasters in U.S. naval history. This is his story.

Of joining the Navy, Paul Murphy said, “I was drafted into the Navy. I felt very fortunate, as it was one of the few times that the Navy did any drafting. I went to boot camp at Farragut, Idaho, and after boot camp I was selected to go to a fire-control school at Treasure Island, California, for four months. After I completed that school, I attended Advanced Fire Control School at San Diego, which was another three months. So, I had seven months of training before I was assigned to the USS Indianapolis. [In the Navy, fire controlmen operate weapons systems aboard surface-combatant ships.]

The Indy was a heavy cruiser that before the war had been the ship of state for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He made two trips on it to New York, a couple down to South America, and one to the Aleutian Islands during the peacetime period.

The Indianapolis had not been at Pearl Harbor during the attack on December 7, 1941; it had been at Johnston Island, southwest of Hawaii, for gunnery practice. The ship participated in 10 campaigns during the entire war, and I was involved in the last five.

At that time, Admiral Raymond Spruance commanded the Fifth Fleet, and so the Indy became Spruance’s flagship; he was in charge of most of the Pacific operations while I was aboard.

I always felt that being in the Navy was a lot better than being in the trenches over in Europe. Those guys had frozen feet, and the mud and the stuff they had to go through—it would have been terrible. It’s pretty hard to comprehend.

If you’re going to be on a ship, it’s best to be on one in wartime. It’s a little more lax than it would be in peacetime—not so much spit and polish. We had all the accommodations anybody could ever want. We had two doctors—MDs—and a dentist. We had a “gedunk stand,” which is an ice cream stand, and we had ship’s service, and a barber. We had good dining facilities and had a laundry we could use. In our off-hours, many of the boys would play cards. Always on Wednesday mornings and Saturday mornings, we had navy beans for breakfast.

I was in charge of the after-control tower; that was my cleaning station, and I also had to calibrate everything. I had a young crew—I was young myself—but I had newcomers on there. They saw me cleaning up around there, and they sat around on the deck reading comic books. One day I got fed up and I said, “Hey, if anybody’s gonna sit down and read, it’s gonna be me; you guys get this cleaning done.”

The ship was 610 feet long, so it was quite large. Whenever Admiral Spruance was aboard, we could see him walking the foc’sle for exercise, talking with somebody from his staff all the time. Admiral Spruance was a fantastic individual. He was probably one of the best admirals in the Pacific. He was also from the city of Indianapolis.

Out in the Pacific, the tropical temperature was quite hot, and we had no air conditioning. Many of the boys who worked in the engine rooms, or slept near those engine rooms at night, would take advantage of sleeping on the upper deck, where the cool breeze could blow over them. On the night we got hit, many of those guys were sleeping in skivvies on the deck to keep cool. I was just one deck below the main deck, and it wasn’t too bad in my quarters. I don’t remember ever sleeping away from my bunk. My friend who was in the after-control tower slept in there because it was cooler than where his bunk was.

I was working with the 8-inch guns; you never fired at airplanes with 8-inch guns. You fired them at surface targets or bombardment. So, I was an observer for most of the time when we were under air attack. I could look out the porthole of my control tower and see what was going on, but many of the guys in my division were in charge of the computers and so forth on the 20mm and 40mm and 5-inch guns. They would be more exposed in the area of an easy attack. I was sheltered by my control tower.

We were involved in the June 1944 Battle of the Philippine Sea, where the carriers again were in operation. They shot down 412 Japanese planes—to this day, the largest number of enemy aircraft shot down in one day.

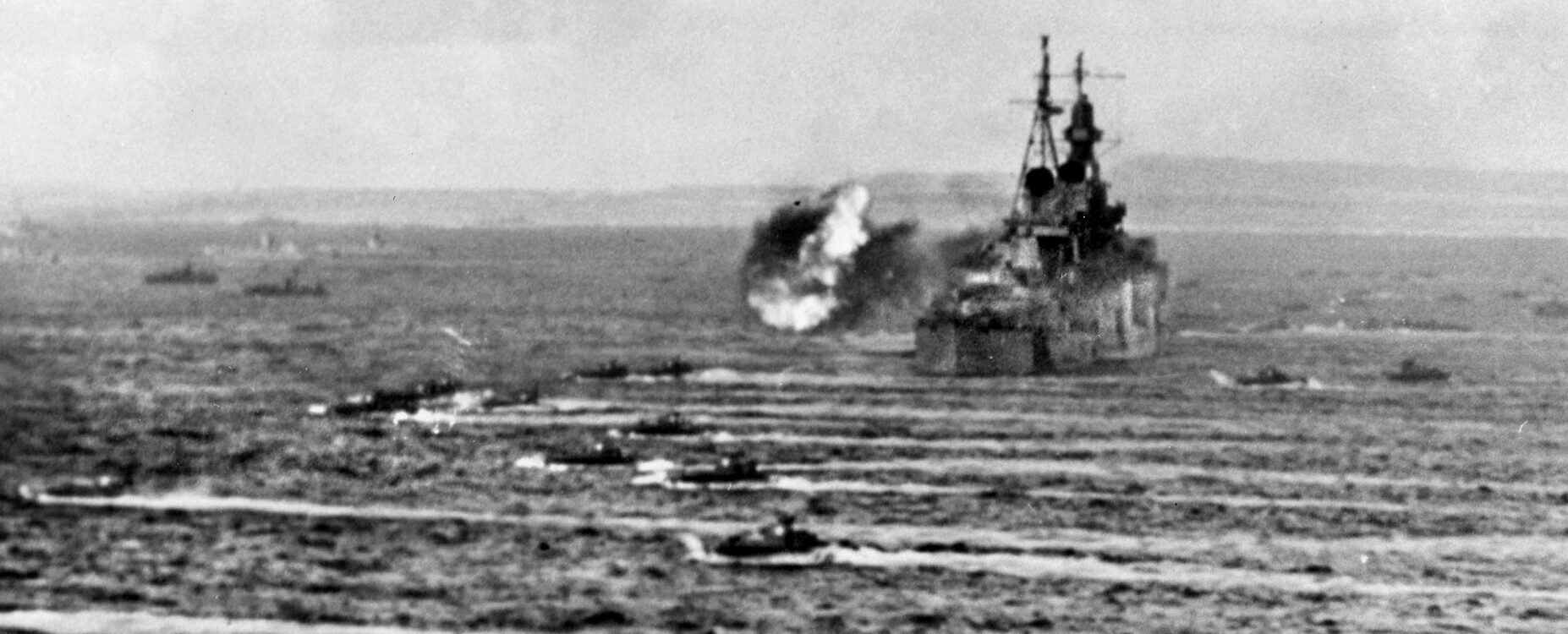

Most of the combat that I was involved in were the bombardments prior to invasions. And we had the flag—the fleet commander—to protect.

In the Marianas operation [June-November 1944], we would go in during the daytime to bombard, but we would leave the area at night to protect the flag, and we would go out to the fresh air and the fresh seas.

There was a terrible smell. We never knew what the stench was until we started to come back in closer to shore, and you’d see the green flies and the Japanese bodies floating on the water—the stench was something terrible. The next evening we’d go back out and get that fresh air again.

I think in the Marianas was the first time that the Navy ever took prisoners and interrogated them. The Japanese wouldn’t give up, but the Navy or Marines brought some prisoners aboard our ship. They were deloused and interrogated there.

After we completed the Marianas operation, our next tour was Iwo Jima [February-March 1945], and in between times the flag would go with the aircraft carriers that made the first carrier raids on Japan.

Iwo Jima was the first time I was made the “pointer” on 8-inch guns. That’s the guy that, after the crosshairs are marked on the target, pulls the trigger, and the computers do all the rest of the work. It was the first time in the entire war that we fired a nine-gun salvo, broadside, at one time. We had three turrets, and each turret had three 8-inch guns. When you fired those shots, you could see the shells go over towards the target, and the roll and pitch of that ship was terrific; we had gyroscopes on board to compensate for that.

I could look through a telescope and watch the shells going over and see them hit a building and blow it up. Fortunately, I had a stool to sit on, and I was looking through the telescope. If I hadn’t had that, my knees were shaking so much that I don’t think I would have done a good job.

The Japanese Navy at that time was pretty short on ships. The only ones out there were fishing boats or scouts that would see you. But we went in there at night, and we didn’t have any losses. I know the Franklin got hit later when we were coming back out. It was hit by a kamikaze, and we could see it burning up.

The Indy then took part in the Iwo Jima operation [February 1945], followed by the Okinawa operation. D-Day for Okinawa was Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945; the day before, March 31, we were attacked by kamikaze planes. We shot down six of them, but the seventh one got through and exploded on the after part of the ship, back toward the fantail. The plane’s engine and the bomb went through the deck and exploded under the ship and blew a large hole in the hull. We lost nine men, and 27 were injured.

After Iwo Jima, we were part of Admiral Marc Mitscher’s Task Force 58 that attacked Tokyo and the Japanese Home Islands. We were only within 10 miles of Tokyo when the Navy made the first carrier raids on that city. We saw the planes fly over; they went in there almost undetected and really bombed the hell out of the place.

The Japanese Navy at that time were throwing everything that could fly at the fleet. There were 151 destroyers involved in that operation, and 121 of them were hit by kamikazes; they were either sunk, or damaged but could be repaired. There were 10 cruisers and 10 battleships also hit; we were one of the cruisers.

We were towed over to an island called Kerama Retto, southwest of Okinawa. During a 24-hour period, working straight through, the Navy put a temporary concrete bottom in the ship, and then we limped back to the States and went into drydock at Mare Island near San Francisco.

In the meantime, Admiral Spruance transferred his flag to the battleship New Mexico; it later got hit by a kamikaze. He then went back to Guam to prepare for the invasion of Japan, and Admiral William ‘Bull’ Halsey took over.

In June 1945, while we were in drydock for repairs, I went home to see my folks. My mother was sitting on the edge of the bed, and she looked like death warmed over. She had a goiter that was sapping all her strength. I scolded dad and asked him why she wasn’t in the hospital. He said, “She won’t go to the hospital until you boys come home.” She had four boys in the service.

So, before my leave was up, my dad and I took her in an ambulance to St. Louis, Missouri, which was 250 miles away. The only reason she wanted to go to St. Louis was because her brothers and sisters were all living there, and she wanted to be near them.

We got her admitted to Barnes Hospital, and I asked the Red Cross for emergency leave so I could be there when she was operated on. But the doctors’ report came back that her metabolism was so bad that they didn’t know when they could operate on her. So, I had to leave her there in the hospital and went back to the ship. I had no communication or correspondence to know how she was doing.

The Indy was in drydock for eight weeks. We finally got our ship repaired, got new equipment like radar and gunnery, and before we had a shakedown, we were called upon to make a speed run out to the Pacific Ocean. Before we left California, a large crate was loaded onto the quarterdeck, where it was bolted down and guarded by Marines. We heard that it was some kind of a new, secret weapon, but we didn’t know what it was; neither did the captain, Charles B. McVay III. We left on July 16, 1945.

We didn’t find out until much later that the cargo we were carrying were the components for the atomic bomb “Little Boy,” which was to be dropped on Hiroshima.

The reason we were selected for this mission was because we were fast, and we were large enough that we could travel alone across the Pacific to the Hawaiian Islands and then from there to the big B-29 base on Tinian Island in the Marianas.

The Indianapolis set a speed record of 71½ hours from San Francisco to Pearl Harbor, at an average speed of 29 knots (33 mph).

We had been told that every day we could shorten that trip would end the war that much earlier. So, we knew we had something on board that was very important. The Navy of course is notorious for scuttlebutt; when you don’t know what’s going on, you make up something. The best thing somebody said about that crate that we were taking to Tinian was that it was 50,000 rolls of scented toilet paper for [General Douglas] MacArthur. But, of course, it was just the atomic bomb.

We reached Hawaii and got refueled and took on supplies and then proceeded on to Tinian, where our cargo was off-loaded. We left Tinian on July 26, 1945. We then proceeded to Guam to get further instructions and supplies. Our instructions when we left Guam were to proceed to Leyte in the Philippine Islands, where we would be met by planes towing sleeves for target practice and be met by the USS Idaho for surface [gunnery] practice. We had about 25 percent new crewmembers, and for at least 250 of them, this was the first time they had ever been to sea, so they needed the practice.

We were told we would not need an escort, because it was safe water there, between Guam and Leyte. At that time, everybody the size of a cruiser, battleship, or carrier was supposed to have a destroyer escort because destroyers had sonar devices and could detect if there were submarines in the area; ships like ours did not have sonar. We left Guam on July 28 and were scheduled to arrive at Leyte on the first of August.

The other instruction we got was that we could zigzag at our own discretion. Zigzagging was supposed to make it harder for a submarine to figure out your course, and harder for them to hit you.

Later we found out that the Navy knew there were enemy submarines in the area, and they also knew the ship USS Underhill had been sunk four days before we got there, on the exact path that we would be taking. But they never told us this because, basically, they didn’t want the enemy to know that we were breaking their code and knew what the Japanese Navy was doing all the time.

On July 29—it was a Sunday—Captain McVay went to the officer of the deck at 10:30 that evening. The moon was hidden by clouds, and it was so dark you could barely see the bow of the ship. So he told the officer of the deck, “You may cease zigzagging. Call me if there are any changes; I’m going to retire.”

He retired to his quarters and shortly after midnight—incidentally, I was on the watch from 8 p.m. until midnight—and I went back to my quarters, which were in the after part of the ship below on the fantail. I went sound asleep.

As I was later told, at about 10 minutes after midnight, a Japanese submarine [I-58] was surfaced, charging his batteries, and observing. Off in the distance, he saw a little black spot and he submerged, raised his periscope, turned 360 degrees, and saw this ship—the Indy—coming towards him; it was not escorted. So, all he did was wait until we passed.

He fired six torpedoes, and two of them hit us. I found out later that the first one blew off about 40 feet of the bow; the second one exploded under the ammunition magazines for the 8-inch guns. Our power was knocked out, so the bridge was not able to contact the engine room to stop the engines. While we were underway with no bow, we took on water rapidly, and that’s what caused the ship to sink so quickly.

When the ship was hit, I rushed to my General Quarters station until the ship started to turn over. When I arrived at the control tower and undogged the door, lying on the deck in there was one of my best friends—a guy by the name of Paul Mitchell; he had slept through the whole thing. I had an extra life jacket and gave it to him and told him to go to his General Quarters station. I later found out that he was able to get off the ship, but he only lived for two or three days in the water.

I was also told later that, after the explosion, they sent one of the officers down to see if he could get the engines turned off, but he got severely burned and never returned topside.

As the ship started rolling to the starboard side, and after about 30 degrees, and quickly going to 45 degrees, the 5-inch guns, which were on the deck below me, were covered with oily water, and all I had to do was step off without jumping off; I swam away as fast as I could. I swallowed a lot of oil and salt water.

Those of us in the water spent most of the night vomiting and throwing up this oil and stuff. The ship went down in about 12 minutes. That’s very fast for a ship that size.

The next morning, when the sun came up, we found two floater nets that had floated off the ship, and we also found two life rafts. We got no lifeboats or anything else off the ship because she went down too fast. In the group that I was with, there were approximately 250 to 300 men. We all tried to stay together. We tied the two floater nets together, and we used the two rafts for those who were most severely hurt and put the injured on there. It wasn’t much better than what we were in, because half of their body was in the water.

Captain McVay had been blown off the deck where he was standing. Ironically, he was one of the guys that found a raft when he got in the water. While he was on there, I think he eventually got as many as seven on the raft. He thought there were no other survivors; he couldn’t see anyone else in the dark until we all started drifting together. You can imagine the thoughts that went through his mind: “I should have gone down with the ship.”

We were in the water for four-and-a-half days without food or [drinking] water. Many of the boys hallucinated and thought that they could see islands and could swim to the shore. Those who went off by themselves were the ones that were most susceptible to sharks. The rest of us tried to take care of each other, but many of the boys hallucinated and, because of dehydration and lack of food, felt that the ship was just below the surface of the water—that they could just swim down and get a cool drink of water.

Many of them took their life jackets off and went down and swallowed salt water, and when they came back up—you can’t imagine what it’s like to see somebody who’s swallowed a lot of salt water. They’re worse than the worst alcoholic drunk you’ve ever seen. They came up and they were wild, and you couldn’t stand to be around them. It was only a short time later—an hour or two hours at the most—that they just went berserk and died. That was the worst tragedy of the whole thing.

The sun was blistering in the daytime. We were getting sunburned from the reflection [off the water] and were praying for the night cool air. At night it was very cold, and we could hear our teeth chattering, and we prayed for the daylight and sunshine. This was repeated.

Probably after the second day, I cut off my shirttail and put it over my head to protect my face and eyes and nose and lips, which were becoming quite festered. I probably didn’t see some of the things that might have been going on during the daytime. A lot of the boys saw sharks’ dorsal fins and so forth. Because I’m from Missouri, I didn’t know a shark from a catfish.

We did have schools of sharks come into our area. We would splash and holler and they seemed to let us alone. I know the sharks or some kind of fish were bumping our legs, and we’d pull our legs up because they were dangling. I also think sharks don’t like Irishmen, because I never had a bite; I was pretty fortunate.

On the fourth day, in mid-afternoon, we saw a plane flying in towards us, making circles, and we thought, “Well, they must be looking for us,” but the funny part was, they were out looking for Japanese submarines, and the pilot was testing a new device, a radio antenna that dropped out of the bottom of his plane to give him longer distance of communication.

Just before he got to our area, the pilot had a problem with the cable that was holding that antenna, and the antenna was flopping around. The pilot, so I’ve learned, got down on his belly in the plane and looked around to fish up this antenna when he saw an oil slick in the water; we had drifted back into our oil slick.

He started to fish up his antenna and quickly went back to his pilot seat and his crew said, “What’s matter?” He said, “Look down and you’ll see.” He immediately opened his bomb bay doors and started to make a bombing run, thinking it was a Japanese submarine and, as he went down to about 2,000 feet, he started seeing heads bobbing in the water scattered over several miles.

The pilot’s name was Chuck Gwinn, and he was flying a PV-1 Lockheed Ventura. We always call him “our angel.” He immediately wired back to his base in Peleliu and told the officer in charge there, who was second in command: “There’s an emergency; send out all possible help.”

They sent one PBY out with supplies; it was another two hours or so before he reached us. He got out there and started dropping supplies and life rafts, water, and food; the water [containers] broke when they hit the surface. His crew saw that there were men scattered over 25 miles. He immediately wired back to the base, and the base commander was in charge then; he had not received the previous message.

He sent one PBY out; the pilot was Adrian Marks of Frankfort, Indiana; he decided to break Navy regulations and attempt to make an open-sea landing because he and his crew saw that the stragglers that had gotten away from groups were more susceptible to shark attacks.

He immediately landed in the water in 8-12-foot swells that popped a few rivets. He could have been court-martialed for that, had the situation not been so serious. He started picking up men. When the other pilot was flying around, he would direct him where to taxi to get the stragglers. Before that evening, when darkness fell, he had picked up dozens of men, piled them in the aisles of his plane like cordwood, and tied the rest onto the wings with parachute shrouds. Of course, he couldn’t take off.

His crew gave each of the survivors half an ounce of water. Then the plane taxied past our group, and we made sure that those who most needed to get out of the water were the first ones to get on.

That was the first time that anybody knew that the USS Indianapolis had sunk. The pilot immediately radioed again, breaking regulations, telling his location and asking all ships in the area to converge on his location. Five ships started coming in to rescue us. The first one that got to us probably got there about two or three in the morning.

As he was approaching our area, knowing that there was the possibility of running over some of the men in the water, he shined his 24-inch searchlight up against the clouds to let all the other ships know where he was, and also to let the survivors know that help was on the way. There’s a debate about whether or not that was a good idea, because many of the men exhausted themselves trying to swim to that ship. I’m sure that some of them succumbed before they could be picked up. That ship took off the 56 men from the PBY and picked up 36 more and proceeded back to the Philippines.

Another ship, a fast-attack transport, was the one that picked me up. They had landing craft on the ship, so they dropped these landing craft off that went around like a lifeboat and picked up survivors and took them alongside the ship. When they picked me up, they took me alongside the ship, and they had a rope ladder down.

I thought that I was capable of climbing up that ladder, but I got up two or three rungs and fell off, so they put me—like they did everybody else—in a wire basket and hauled me up to the deck, cut off our clothes, which were black from the oil, and put our oil-soaked bodies on the shower floor. The crew tried to wash off the diesel oil and then they gave up their white bunks for us survivors. That ship picked up 151 men. We left that ship in a mess.

We headed immediately for Samar in the Philippines. When we arrived there, they trucked us over to the hospital. I remember that I was lying on a rubber-sheeted bed, and they poured liquid penicillin over my entire body to heal the salt-water ulcers and sunburns.

I don’t know to this day how long I was there [in the hospital], but I think it was close to 10 days. Then we were all flown from there to Guam in a cargo plane, set on the floor. When we got to Guam, we entered a submarine rest camp, which was just ideal. Those who were still in pretty bad shape went to a hospital. The rest of us recuperated in the rest camp. We had steak every night, beer if we wanted it (I never liked beer), and they served gallon buckets of ice cream—every night.

Eventually, we all gathered, and the USS Hollandia, which was a small carrier, took the whole entire group to San Diego. We arrived at the end of September—remember that we were sunk on July 30. We disembarked there and were given 30 days’ survivors’ leave.

Hiroshima was bombed on the 6th of August, Nagasaki on the 9th of August, and the Japanese surrendered on August the 15th. That was the first time the newspapers announced that the Japanese had surrendered, and that the USS Indianapolis had been sunk with 100 percent casualties.

You can imagine what it was like for those parents to hear that. My dad received a telegram that said I was wounded but that I was recovering. The Navy kept it quiet until such time as they could put out that, more importantly, the war had ended.

On the Indy, 880 had lost their lives. Of that 880, probably near 300 died when the ship went down, and the rest died in the water because of the delay in rescue and so forth.

When I left San Diego to come home, I went back to Missouri on a train. Trains back then were the filthiest and the slowest. The windows had to be open, so all the coal smoke from the engine came in. But we got home okay.

I hadn’t told anybody that I was coming home, but when we got to Kansas City, I figured I’d better call home; I didn’t know what condition my mother was in, or anything. A gal who was taking care of the house while dad was working answered the phone. I asked if he was there and she said, no, he’s working. I said that this is Paul and I’m on my way home and will be in Chillicothe in an hour or two and just let him know that everything’s okay and he doesn’t have to meet me. So I get to Chillicothe and he’s there. It was quite a reunion. My mom had made a full recovery, too.

I don’t ever want to hear anybody condemn the U.S. for dropping those atomic bombs—they saved many American lives and Japanese lives, because if we had had to invade, the Japanese would not have given up.

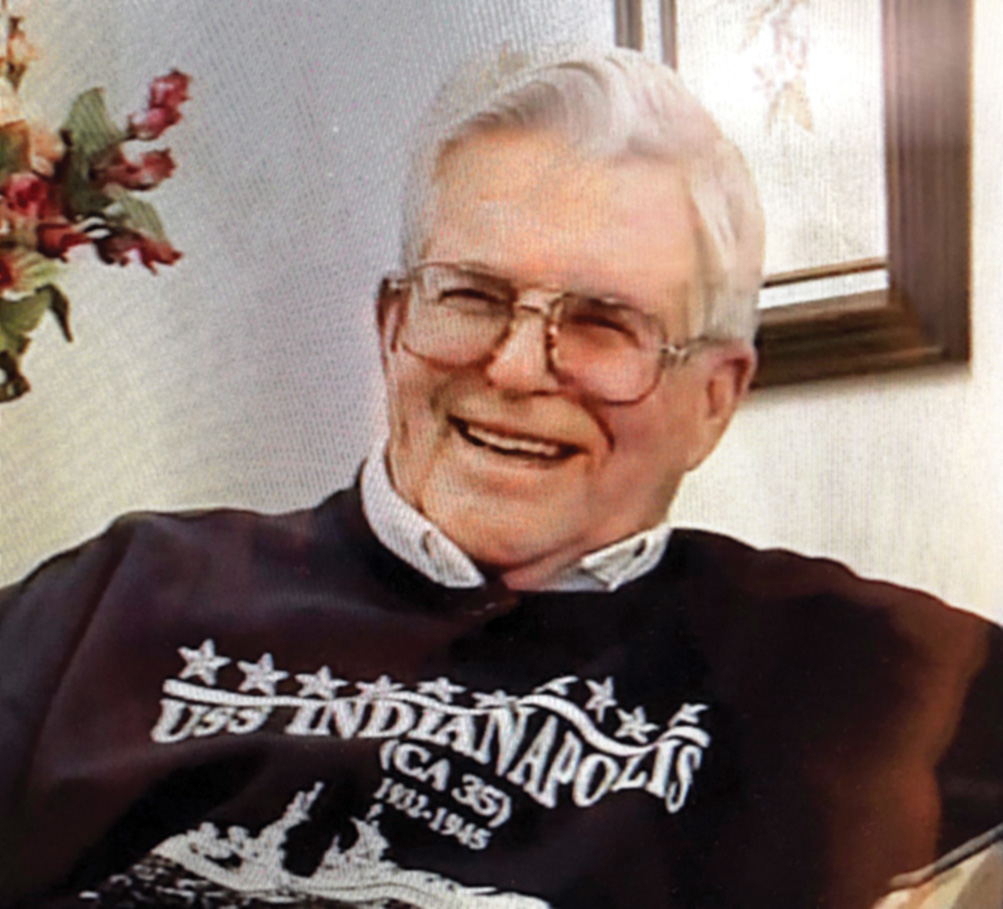

After his honorable discharge in 1946, Paul Murphy attended the University of Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy and graduated with a mechanical engineering degree. In 1951, he met JoAnne Simons and moved to Chaska, Minnesota, where they had five children and where he managed the Simons Lumber Company for a number of years.

Shortly after his divorce in 1975, he moved to Broomfield, Colorado, to join his brother’s engineering firm, W.M. Murphy & Company. In 1987 he married Mary Lou Walz and became very active in his community, becoming a co-founder of the Broomfield Veterans Museum and the Colorado chapter of the USS Indianapolis Survivors Association, which he served as treasurer, vice-chairman, and chairman for a period of over 20 years. With a commitment to tell the story about the sinking of the Indy, he presented to hundreds of school and service organizations over the years.

Paul died peacefully at age 91 on February 21, 2016, at the Colorado State Veterans Home in Aurora. He is buried in the military section at the Broomfield Commons Cemetery

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments