By Keith Buchanan

The Nelson King, a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber, was en route to Berlin on March 6, 1944, when it flew into a whirlwind of Luftwaffe fighters. It was fighting its way through the attack when the wing of a Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter ripped through the huge square “D” on the bomber’s tailfin.

Tail gunner Lieutenant Joe Greasamar was knocked out cold by the impact above his head. He woke up lying flat on his back with a view of the sky above. He thought he was falling but soon realized he was still in the bomber. When he got his senses about him, he resumed manning his guns. He did not know that a German fighter had almost torn his bomber in two.

The “Bloody One Hundredth”

The story of the bomber’s last mission had begun at Thorpe Abbotts, a hamlet in England about 90 miles north of London, home for over 3,500 Allied airmen and support personnel from 1943 to 1945, and involves the heroism of Nelson King during an earlier run to Bremen, Germany. Thorpe Abbotts was the headquarters of the B-17s of the “Bloody One Hundredth,” also known as the 100th Bomb Group of the Eighth Air Force. At that time, one in seven residents of Thorpe Abbotts and surrounding Suffolk County was an American.

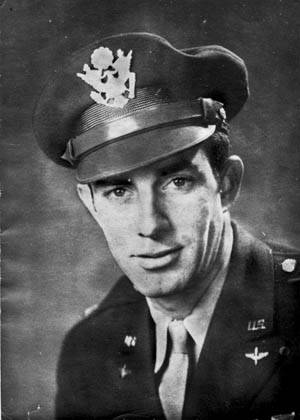

The Nelson King’s crew was led by its pilot, Lieutenant Frank Lauro, who until joining the service had been the youngest member of the New York Stock Exchange. Other crewmen included co-pilot 2nd Lt. Emanuel “Joe” Greasamar, a lanky Ohio farmboy and part-time midget car racer. Ball turret gunner Sergeant

Murray Schrier had worked in his father’s hotel in New York, while top turret gunner Sergeant Dewey Thompson was from North Carolina. Sergeant Bill Heathman, from Warren, Ohio, was the right waist gunner, and Sergeant Nelson King, an oversized farmboy from Kansas, was the radio operator. At that time, the bomber had no nickname or logo painted on the nose. That would come later.

The “Bloody One Hundredth” was a most apt sobriquet for this group of airmen. Fewer than one in four could expect to complete his tour of duty in a B-17, at that time 25 missions. Two-thirds of the men could expect to die in combat or be captured. An additional 17 percent would either be wounded seriously, suffer a mental breakdown, or perish in an air accident over Allied soil.

Returning Under a Black Sky

On the cold Monday morning of their ninth mission, the crew arose with the normal 2:30 wake-up call and prepared for the flight to Bremen to drop their 4,800 pounds of ordnance. The bombing run was made with few problems, a milk run as the crew put it. The return trip to England was what made it unusual.

The sky was overcast, and after releasing the bombs, the entire bomber group climbed up to 35,000 feet, both to get clear of clouds and to avoid the Luftwaffe. Sergeant Schrier recalled that after they finally stopped climbing and the sky was no longer blue, but black, the temperature had fallen to 60 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. Without a pressurized cabin, the temperature was miserable for the crew.

Frozen Oxygen Bottles

Schrier watched for fighters, feeling comfortable that there were none at this altitude. Crammed into the ball turret, Schrier could not wear a parachute, and at five feet, nine inches he was too tall to wear his boots, but his three pairs of insulated socks provided sufficient warmth for his feet. He knew something was wrong, however, as he was having problems breathing.

Being in the turret, he was not connected to the oxygen lines running throughout the bomber; he used portable oxygen bottles instead. The problem was that oxygen contains moisture, which freezes quickly at low temperatures.

“We had seen up to negative 52 degrees before with few problems,” Schrier recalled. “The oxygen line might have a bit of icy slush in it, but we would massage the tubing with our hands and have no breathing problems. On this day, it was frozen solid. Nobody ever told us those oxygen bottles would freeze up. We were young and didn’t think of those things. They didn’t at minus 52. I knew something was wrong because I wasn’t breathing right.

“I called up to Lieutenant Lauro,” he remembered, “and said I was going to get out of the turret and told him why. He understood and knew it was bad by the way I was breathing. I made up my mind to go to the radio room where there was an extra mask. I called to Nelson King, the radio operator, on the intercom, to get a mask ready for me. I finally got everything unplugged and headed for the radio room. I crawled to the room, got my hands on the doorknob, and remembered nothing else for a while.”

King came out of the radio shack and, with help from with right waist gunner Bill Heathman, pulled Schrier to an outlet where they could plug a mask into the main oxygen lines. Both King and Heathman were now on portable oxygen bottles, not knowing that the bottles were the cause of Schrier’s breathing problems.

Four Crewmen Passed Out

King struggled to get the oxygen mask over Schrier’s face and helmet. As the mask was a different type from the one Schrier had been wearing, it would not fit onto his helmet. King fumbled with his heavy gloves trying to get the mask in place. The oxygen mask hooked onto two small fittings on the helmet in the old-type system the crews first used, and it was an old-type mask King was trying to fit to Schrier. The only thing King could do was to tie the mask around Schrier’s helmet. To accomplish this, he had to shed his multiple layers of gloves, exposing his hands to the frigid air.

As King was doing this, Heathman became exhausted, getting no oxygen from his ice clogged bottle. He crawled toward his waist gun position, helped by the other waist gunner, Gerald Will, who had also hooked into one of the troublesome bottles. Will was having breathing problems and would soon pass out. Heathman was able to call forward for help before he too passed out.

Meanwhile, King’s bottle had also clogged with ice, and as he finished the job of tying the mask to his ball turret gunner’s helmet, he toppled over on Schrier. Oxygen was now finally coming through to Schrier, however.

A Freezing Crew

Lieutenant Lauro had a major problem. Four of his crewmen were now out of action. Not getting a response from anyone in the rear of the plane, he sent Greasamar and bombardier Walt Green back to check on the four men. As if all this were not bad enough, Lauro noticed the number two engine acting up as several German Focke-Wolfe Fw-190 fighters eased up to the edge of the group’s formation.

If the Germans had known of the situation inside the B-17, they would have surely attacked the easy target. The fighters made one run at the B-17 formation, but navigator Emery Horvath and top turret gunner Dewey Thompson sprayed them with enough machine-gun fire to deter their return.

Meanwhile, Greasamar was hard at work in the radio compartment getting oxygen to Schrier and King, while Green was helping Will and Heathman. Schrier revived first, and Greasamar was able to get him up into the co-pilot’s seat. Schrier explained that Lieutenant Lauro gave him a funny look, so he told him what was happening. Schrier’s electrical suit was not working, and the longer he sat there the colder he got.

“My whole dang body was shaking at one time,” he remembered. “Lieutenant Lauro told me to talk to him and I said I couldn’t.”

It took a while before the shivering stopped, but now Schrier realized he could not see. The moisture in and around his eyes had frozen. Had he spent much more time in that cold, he would have lost his eyesight.

Greasamar was facing a much worse problem assisting King, whose bare hands had been in the cold for approximately 20 minutes. His hands were not frostbitten, they were frozen. With Green assisting Greasamar now, both crewmen worked to get oxygen to King. Greasamar put King’s hands inside his armpits to warm them. It was too late.

King eventually came to, but his hands were numb. He began to thrash around the radio compartment, lashing out with his numb fists, which by now had swollen to the size of grapefruits, trying to bring feeling to them. As he hit the sides of the ship, bits of frozen flesh flaked off like chunks of ice. King’s hands did not bleed and would not until they were within sight of the English coast and below 5,000 feet altitude.

Naming the Plane the Nelson King

The bomber was met by ambulances and doctors as it landed. King was immediately taken to the hospital. Schrier was also taken in for a medical examination, but was back in the Fortress in time for the next mission. Both Heathman and Will were okay, having passed out for only a short time.

“I didn’t see King’s hands until we got down on the ground,” Lauro later said. “Frostbite was no word for what happened to his hands. One of the flight surgeons looked at them, and I looked at the doc, and what he must have been thinking wasn’t pretty. King saved Schrier’s life with those hands.”

As a token of their admiration, the crew named their plane the Nelson King. King was awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action while serving as a radio operator and gunner.

Bombing the “Big B”

The second memorable mission came on March 6, 1944, to the “Big B”—Berlin. After the war, Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring said that the day he saw Americans over the skies of Berlin, he knew “the jig was up.” Monday, March 6, 1944, was that day.

After their early wake-up call, the airmen made their way to the base operations buildings and their briefing rooms. In the early morning cold, they chatted loudly, both to help keep warm and to steady nerves. Those nerves quickly became unraveled when the briefing officer pulled back the curtain over the map of the day’s mission. The map had red tape marking the route that went on and on and on—eventually to Berlin! The targets were the Bosch works, the Erkner ball bearing plant, and the Daimler-Benz aircraft engine factory. The Eighth Air Force was delving for the first time deep into the heart of the Third Reich. Allied leaders knew that the Germans would defend their capital city.

Allied air strategists were willing to sacrifice bombers to entice German fighters into the air to take on Allied fighter escorts. They hoped to substantially weaken the Luftwaffe in a war of attrition as the Germans lost fighters and experienced pilots they could not replace.

Leading the Bombing Run

Casualties came early on March 6 as a Consolidated B-24 Liberator of the 392nd Bomb Group ran into a patch of mist just off the end of the runway, struck a tree, and burst into flames. All crewmen were lost. Bombers that followed had to fly past the burning wreckage.

Once over the English Channel, all gunners fired off short bursts to test their guns. One B-17 of the 385th Bomb Group had a cartridge case from an aircraft above smash through its nose and had to turn back. Over the North Sea, 44 other bombers dropped out for various reasons. Eighteen B-17’s of the 384th Bomb Group were crowded out of their formation by another bomb group and were unable to catch their group in order to fly in the protective box formation. All 18 abandoned the mission and returned to base.

The box formation theoretically gave bombers sufficient firepower to ward off attacks. The formation was made up of 21 bombers divided into three squadrons: the lead squadron with six, the low squadron with another six, and the high squadron with nine aircraft. The high and low squadrons flew on opposite sides of the lead, with the formation taking the shape of the letter V but tilted at a 45 degree angle as viewed from the rear. The entire flight of hundreds of bombers was divided into boxes to give mutual protection from roving bands of German fighter planes. This was maintained for the entire flight.

The Eighth Air Force sent close to 1,500 fighters and bombers into the air that day. Included was Combat Wing 13B of the 418th Squadron, 100th Bomb Group, and the Nelson King. Wing 13B was broken into lead, high, and low squadrons with a total of 21 B-17s taking off from Thorpe Abbotts. The Nelson King was the lead plane in the lead squadron. Wing 13B flew adjacent to Wing 13A, 12 miles behind Wings 4A and B and 12 miles ahead of Wings 45A and B. Six wings comprised the 3rd Bomb Division, consisting of 252 B-17s.

The 1st Bomb Division, 315 bombers, led the way followed by the 3rd, with the 2nd Bomb Division, 243 bombers, flying caboose. This flying freight train of death stretched for over 96 miles.

Gaps Between the Bomber Wings

For this important mission, Lauro again piloted the Nelson King, but sitting in the righthand seat was Captain Jack Swartout. With the Nelson King guiding the lead squadron of Wing 13B, Swartout’s reputation as a fighter pilot and one of the best lead pilots in the 100th Bomb Group made him a natural to assist Lauro and crew. Regular co-pilot Joe Greasamar moved to tail gunner, a position for which he was not trained.

The mission went smoothly until the Nelson King crossed the North Sea. There, the gap between the 4th A and B Wings (leaders of the 3rd Division) and the 13th A and B Wings (middle of the 3rd Division) grew from 12 miles to 20 miles.

In addition, the pathfinder bomber leading the 1st Bomber Division developed radar problems. The 1st Division and the 3rd Division back to and including the 4th A and B Wings had drifted south of the planned route. Given the 45-mile-per-hour wind, the 1st Division was drifting away at the rate of one mile for every two minutes of flying time.

The navigator had adjusted the 3rd Bomb Division for the wind and with radio silence being enforced assumed that the lead group was merely gaining ground on the others, not heading on an entirely separate path. The Nelson King soon became the lead plane in the lead squadron of not only its box, but also the entire remaining bomber force.

The Luftwaffe Exploits the Gap

Luftwaffe ground tracking and radar posts saw the gap between the groups as well. The Luftwaffe borrowed tactics for the bombers and their fighter escorts from the German Navy and its ability to concentrate U-boats into a “wolf pack” when launching an attack. To do this against escorted bombers, the Germans would attack with the greatest number of fighters in a concentrated space. If the bombers had escorts, generally three groups of fighters attacked. Each group typically consisted of 30 to 40 fighters. Two groups would attack the fighter escorts, and the other would attack small groups of bombers.

The Germans pilots knew the best attack positions, given their strengths and the bombers’ weaknesses. By this stage of the war, they always tried to attack from a head-on position or in a high-speed dive from above, coming into a level position. If they attacked from the rear (which the B-17’s were designed to protect), they faced up to six .50-caliber machine guns. However, if they attacked directly toward the front and from a 12 o’clock position, they usually had to face only one or two machine guns. The German fighters needed to average 20 hits with 20mm cannon rounds to knock out a bomber from the rear; that average dropped to four or five from the front. Usually a single hit anywhere in the nose was good enough to send the bomber down.

With a closing rate of 200 yards per second, there was little time to line up a clear shot, but the German fighter pilot had a much larger target to sight than his counterpart in the B-17. The German pilot’s goal was to make a half-second burst from his guns at about 500 yards from the bomber, then pull directly up to avoid ramming it.

Only eight Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighters protected the separated half of the 3rd Bomber Division, while 31 guarded the trailing 2nd Division. The Germans chose their target well. Their force came directly at the 3rd Division, Wing 13B with a total of 107 Me-109s and Fw-190s. The German fighters attacked like a swarm of bees, coming in waves, flying by so fast it was difficult for the B-17 gunners to get a fix.

Joe Greasamar, sitting in the Nelson King tail gunner position, fired his guns until they became too hot to touch. Having never had training, he just shot at everything. “The guns were so hot, they continued to fire after I let off the trigger,” he explained. “The heat from the guns was causing the bullets to go off on their own.”

Dropping Out of Formation

Ten B-17’s, each with 10 men aboard, went down with the first wave. Of the nine bombers in the high squadron of Wing 13B, six were trailing flames afterward. The attack took less than a minute.

“They came down from very high and on our right at tremendous speed, making long sweeps at us,” said Lauro. “They came in five abreast and about 12 deep. All of them concentrated on our one group. We put up a terrific screen of fire. In wave after wave they poured down on us, five ships at a time, picking on just one or two bombers.”

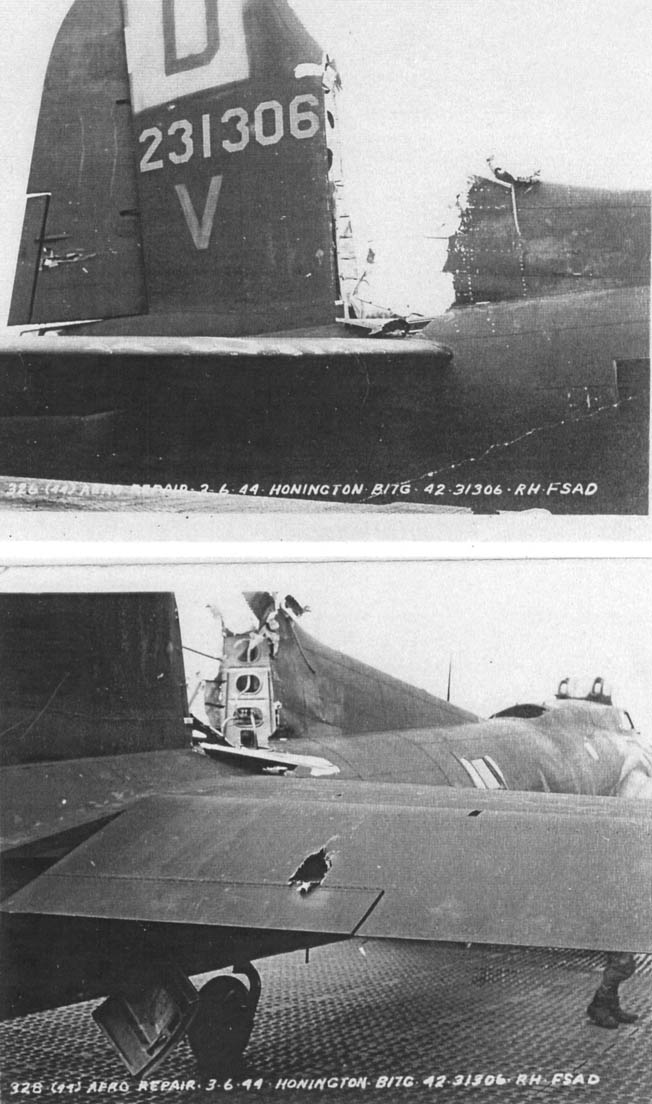

Just behind the wave, a single Fw-190 headed straight for the Nelson King. It fired, then pulled up just enough to clear the front of the bomber but not the rear. The Focke-Wolfe hit the King and tore off part of the vertical fin and rudder. Swartout felt the King shudder; even with both he and Lauro at the controls the bomber became incredibly difficult to handle.

With the King slowing, Swartout and Lauro dropped out of the formation. Realizing the crippled bomber would never make it back to England alone, they decided to trail the formation to Berlin. Swartout next dropped the bombs to reduce the weight, hoping to maintain as much airspeed as possible.

“I’m Hit, I’m Hit”

Again, all hell broke loose. “They just lined up tail to tail and started circling us like Indians used to make war on a lone covered wagon,” said Lauro. “Occasionally one or two of them would peel off for a head-on attack. These were the worst of all.”

A lone Me-109 showed up from out of nowhere and fired several of its 20mm shells at the King. One of them exploded in the right side of the cockpit, wiping out the instrument panel, the hydraulics, and the on-board radio communications and starting a fire.

“I’m hit, I’m hit,” Swartout yelled, as he thought he was wounded. It didn’t take him long to realize he was merely covered in hot, red hydraulic fluid, although the butt of the shell did hit him in the chest severely enough to knock his breath out. Engineer Dewey Thompson came down from the top turret to assist, attempting to put a tourniquet on Swartout, who signaled that he was okay.

The King had two engines out, the number three gas tank pierced, and the oil cooler line damaged. The ball turret was covered in oil, making it impossible to see out. The top turret was soon put of commission as well by another shot. The cables to no. 4 engine were shredded, and other systems were inoperative. The King could only reach a speed of 140 miles per hour. Anything more threatened further damage to the tail fin due to vibrations.

Evasive Maneuvers

The King was a sitting duck for the Germans. With the intercom out and a hole in the side of the pilot’s cabin, the roar of the rushing air made it impossible to hear. Swartout looked at Lauro, tore off his headphones, and motioned that he was taking control of the plane.

The crew prepared to abandon ship, but Swartout had other plans. He ordered them to be ready to bail out but to hold steady until at least he made an attempt to fly home. With fighter pilot skills acquired in a P-47, he worked to evade the frontal attacks by the fighters. It took all of those skills to carry on the mission.

With a good part of the oxygen system damaged, the rear gunners passed around oxygen bottles. Swartout guided the King toward Berlin, circumventing the flak and bombing runs, then intersected with the 390th Bomb Group that had just made its run.

Flying at a lower altitude, the Americans were below the flak bursts, but three shells blasted through their wings and burst high above. Enemy fighters were still lining up to finish them off. Swartout guided the King under the higher 390th and up the formation’s side away from trouble. As the other bombers stayed in their box for protection, Swartout dipped Nelson King and moved from side to side of the 390th to evade the attackers. He did this for a long time, doing everything possible to keep the damaged aircraft from the Germans.

The Germans were known to fly into American formations with captured B-17s and shoot down or ram Allied planes. With the King flying the odd routes to evade enemy fighters, other B-17 crews wondered if it had German pilots. One airman kept calling the leader of the 390th, telling him that a weird B-17 was out there leading bandits to their formation. The leader told him to keep an eye on it and to shoot it down if it ran away. Then, when a damaged Lockheed P-38 Lightning eventually attached itself to the King’s left wing for protection, Swartout knew he would not be fired upon by Americans.

80 Downed Aircraft

What few operational guns were left on the Nelson King were ready and waiting for another attack. It was then that a group of P-47s and North American P-51 Mustang fighters showed up, bringing a sense of relief to the beleaguered bomber’s crew.

The Nelson King made it back to England. Its crew had suffered only two minor wounds. Of its 21-plane squadron, 11 did not return. They were the Kind-a-Ruff, Lucky Lee, Spirit of ’44, Sly Fox, Terry and the Pirates, Ronnie R, Pride of the Century, Goin Jessies, plus the unnamed 238059 LD A and 231800 LD U. Snort Stuff landed safely in Sweden. These 11 incurred 43 casualties with an additional 57 becoming prisoners of war.

The March 6, 1944, raid on Berlin cost the Eighth Air Force 69 bombers and 11 fighters. The Bloody One Hundredth lost 150 crewmen. Thorpe Abbotts airfield was deathly quiet after the survivors landed and reports of the raid made their way out. A pall fell over the base. Many airmen wanted to be alone. Others drank more than usual that night.

“This is the Closest We Ever Came to Not Coming Back”

The Nelson King did not land at Abbotts. The bomber was so shot up that patches of sky could be seen through the wings, tail, and fuselage. Air controllers refused to let it land and sent it on to the base at Honington, England, where it had to be completely made over.

Jack Swartout was awarded the Silver Star for his efforts in bringing the King home and saving the lives of his fellow airmen.

Joe Greasamar wrote to his parents that night. “Boy oh boy, they about got us today. This is the closest we ever came to not coming back. We got our ship all shot up but we got home. We were one of the very few to get back…. We went to Berlin … no wonder,” he finished his letter.

In May, a new crew headed by pilot Lieutenant Ehil J. Stewart took over the Nelson King. The Nelson King was shot down on May 24, 1944, near Wittstock, Germany, with three killed and seven taken prisoner. By the end of World War II, the Eighth Air Force would have more fatal casualties, 26,000, than the entire United States Marine Corps during the war.

The Lucky Bastard Club

The only serious casualty for the first crew was Nelson King, and he survived. King, losing part of his hands saving his buddies, spent almost two years in recovery. In 1947, Murray Schrier and Bill Heathman visited the man who saved Murray’s life. King was living in Nebraska, farming, and had started a church.

In a series of surgeries, all of King’s fingers and thumbs were gradually amputated along with parts of both hands. The surgeons slit a portion of each hand between the bones of the middle and ring fingers to create claws. This allowed Nelson to write and drive a car. Schrier said King told him that he held no animosity toward anyone for the predicament he got into that cold day in November and lived with his handicap peacefully for the rest of his life.

The tour of the original Nelson King crew ended in early April 1944. Initially, it was to last 25 missions, but as casualties mounted it was increased to 26 and later to even more. Due to a shortage of ball turret gunners, Murray Schrier had to fly 26 additional missions in Italy, where the odds of survival were improved.

With the end of their tours, the crew automatically became members of the Lucky Bastard Club, for those lucky enough to survive the flak and Luftwaffe and live to tell the tale. Schrier, with 52 missions to his credit was a Double Lucky Bastard.

Emanuel “Joe” Greasamar was my Grandfather, and it is so awesome to find an article about the 2 of the several missions I have heard about from my dad. Unfortunately I never got to here them from my Grandfather. Fortunately my Great Grandmother kept all of my Grandfather’s letters, and we now have them archived in chronological order. It brings me great pride to know that my Grandfather took part in that war against evil, and I loved reading a little bit about it. Thank you

Such a great article ability our close friend, Scott Greasamar’s Dad! I knew most of this story but was fascinated to learn more.

What heroes Joe Greasamar and the rest of the crew of the Nelson King were!

Great men from a great generation, who fought for the freedom we enjoy today. Lest We Forget ????

The name of the pilot that got killed on the Nelson Kings last mission was Lt. Emil Siewert. Not Ehile Stewert.

Great story…