By Edward Holub and John Marchetti

“For God’s sake, if Mr. Forrest will let me alone, I will let him alone. You have done all you could, and more than expected of you, and now all you can do is save yourselves.” Thus ended the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads. Union forces under the command of General Samuel Sturgis retreated after being soundly defeated by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, adding to the legend of Forrest and frustrating Union plans in Mississippi.

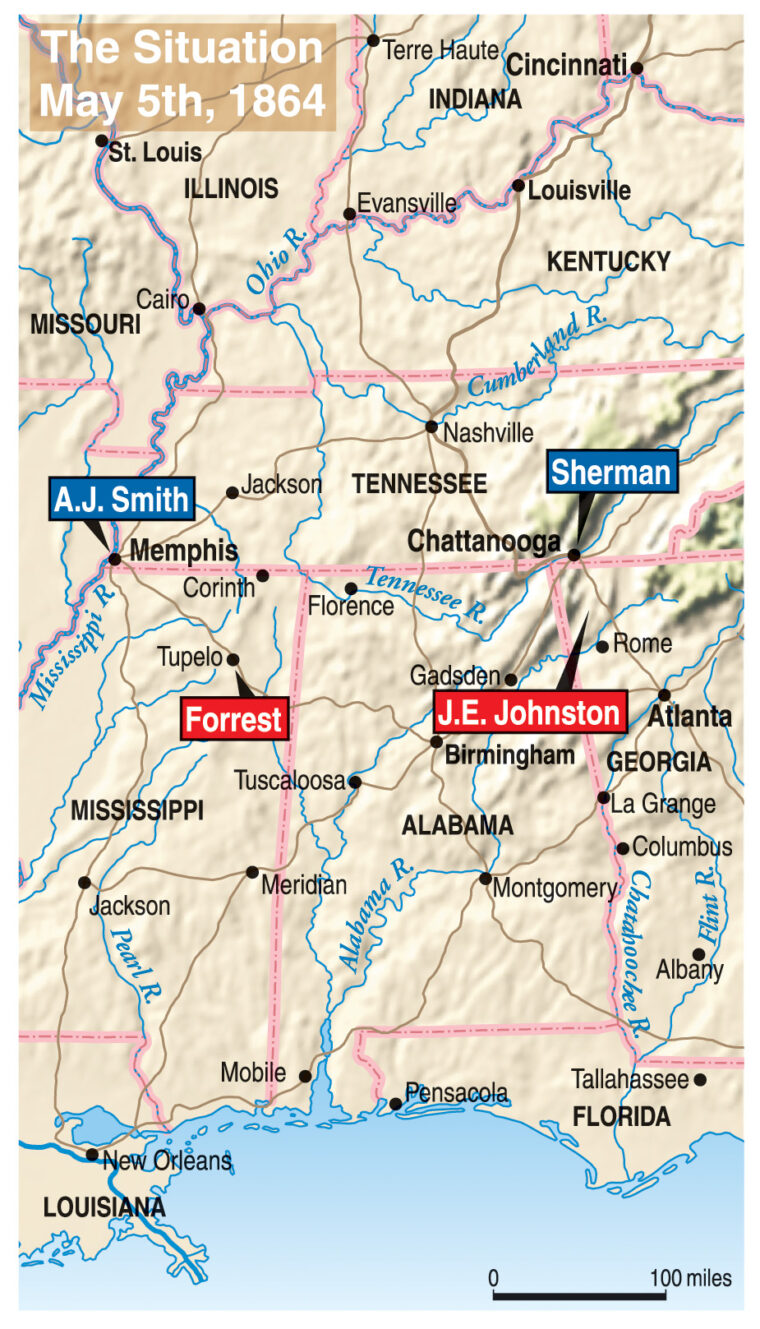

The defeat of Sturgis on June 10-13, 1864 by an inferior force of Confederates was another in a long line of Union attempts to remove Forrest as a threat in the western theater. After Sturgis’s retreat, General William T. Sherman, the theater commander, began to devise a plan to remove the problem. “I have two officers at Memphis that will fight all the time … [A.J.] Smith and [Joseph] Mower … I will order them to make up a force and go out and follow Forrest to the death if it costs 10,000 lives and breaks the treasury. There will never be peace in Tennessee until Forrest is dead.” With these orders Sherman launched a third raid into Mississippi in June and July 1864 to remove a potential threat to his supply line and to defeat his most able and persistent adversary.

Sherman at the time was marching on Atlanta in response to orders issued by the Union’s new supreme commander, Ulysses S. Grant. Grant’s strategy involved moving Union armies in a concerted effort to destroy the rebellion in one final campaign. Sherman’s armies had as their objective Atlanta, one of the most important industrial, communication, and transportation hubs in the South.

Mower was Promised the Rank of General… if He Killed Forrest

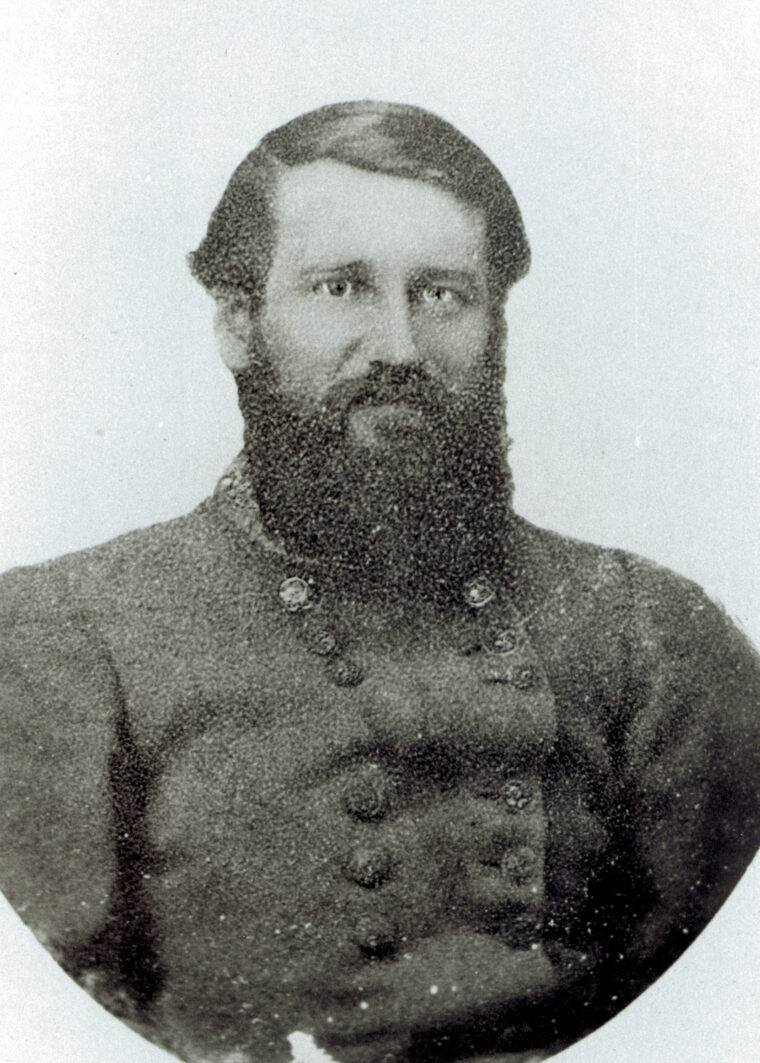

The two generals tapped by Sherman were more than capable. Andrew Jackson Smith, commander of the right wing of the XVI Corps, was a West Point graduate (class of 1838) who had served in the Regular Army with the 1st Dragoons and had service in the West, reaching the rank of major before commanding the 2nd California Cavalry at the start of the war. He resigned to become cavalry chief for General Henry Halleck, participated in several western campaigns, and became a major general.

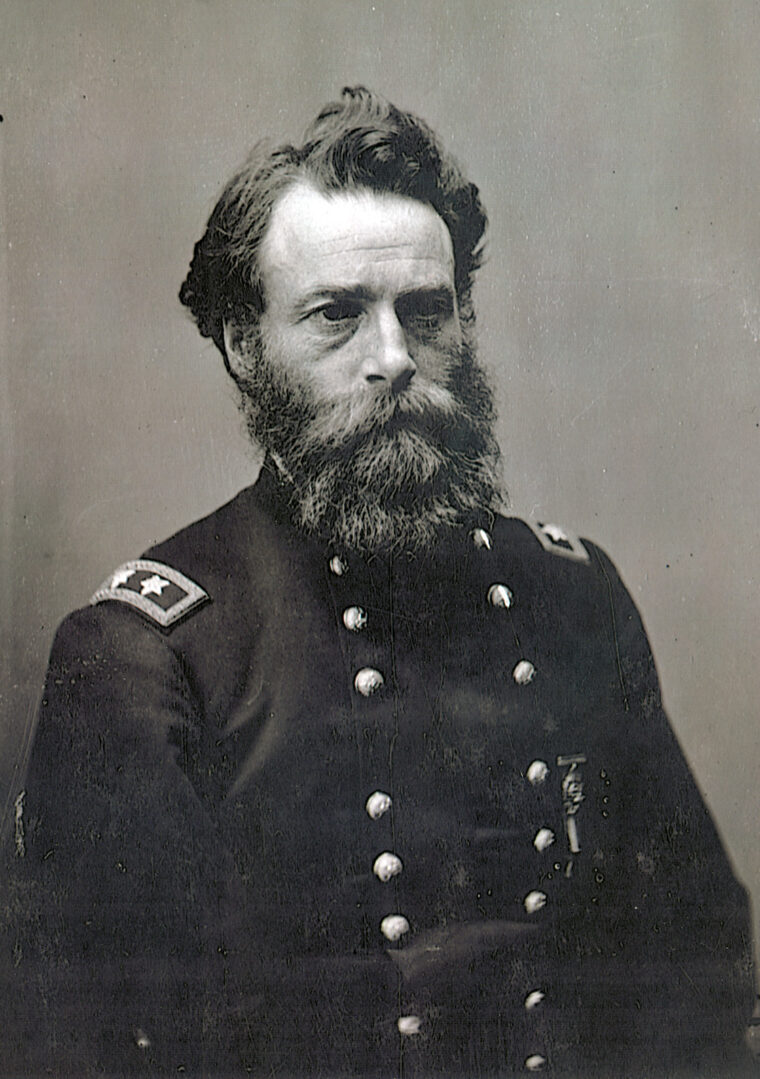

General Joseph Mower, commander 1st Division, XVI Corps, was one of Sherman’s favorite generals. Calling him “one of the boldest young soldiers we have,” Sherman promised Mower a major general’s commission if he was successful in killing Forrest. Sherman even went so far as to convince President Lincoln to keep his promise to Mower should something happen to him. Mower entered army service as a private in the Mexican War and returned to the army seven years later as a second lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Infantry. He rose in rank as the war progressed.

With the defeat at Brice’s Crossroads, General C.C. Washburn, the department commander, acted on Sherman’s orders and told Smith to prepare his command for an advance into Confederate territory. A.J. Smith’s command was a diverse one. It was comprised of his own command, the right wing of the XVI Corps, which was composed of the 1st Division under Mower and the 3rd Division under Colonel David Moore. To this would be added the 1st Division of the XVI Corps Cavalry under General Benjamin H. Grierson and Colonel Edward Bouton’s Brigade of U.S. colored troops. Smith would also have about 20 pieces of artillery. In all, approximately 14,000 Union troops would be involved in the operation. Smith organized his command first at Memphis and then at La Grange, Tenn. By July 1 he was ready to begin.

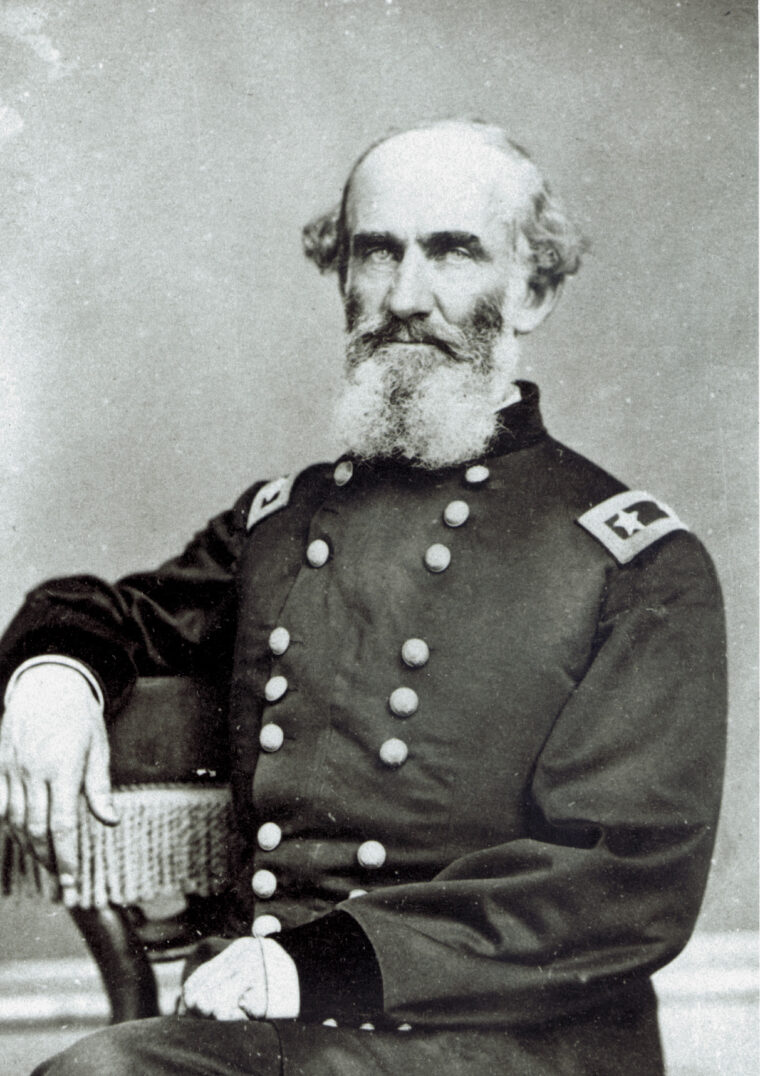

Opposing Smith’s 14,000 men would be Confederate Lt. Gen. Stephen Dill Lee’s troops of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana. Lee (no relation to Robert E. Lee) was the youngest man to reach the rank of lieutenant general on either side during the war. He was born in South Carolina and was graduated from West Point with the class of 1854. An artillerist by training, he served in the East until Sharpsburg, transferring to the western theater in time to participate in the siege at Vicksburg where he was captured and eventually exchanged. After his parole, Lee was promoted to major general and given department command.

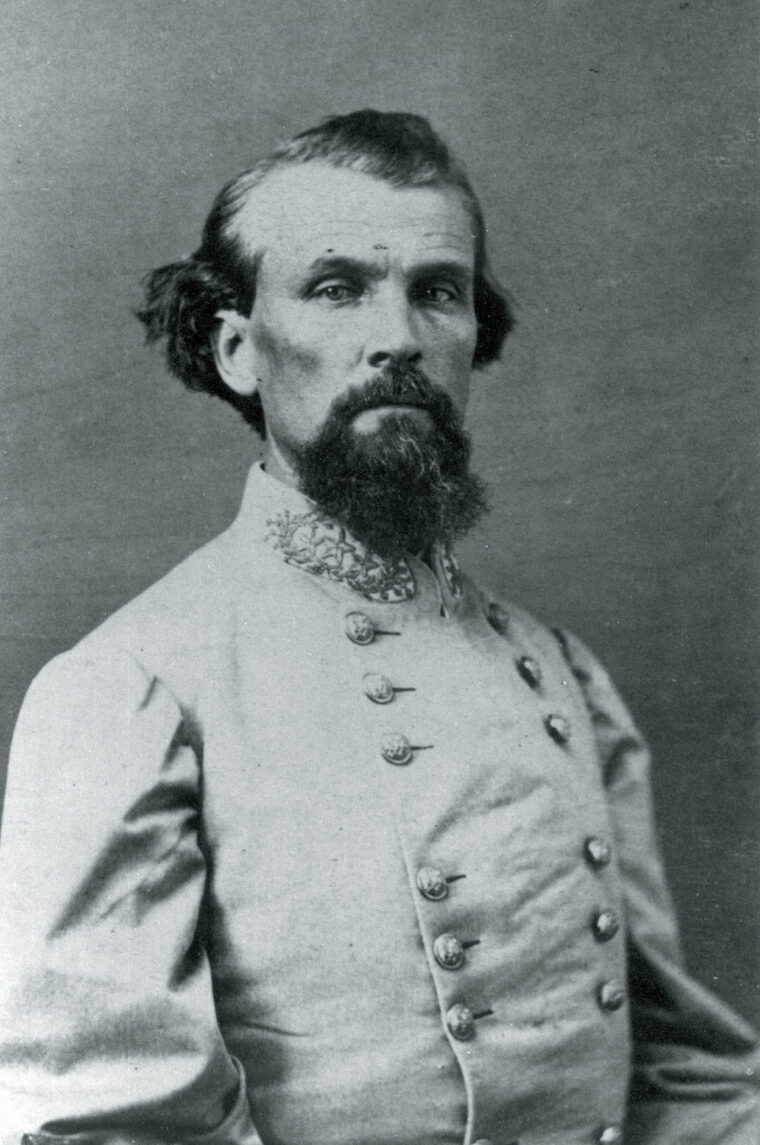

Serving under Lee in the department was one of the most capable and feared commanders produced by either side during the war: Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest was not a military man by training, but rather a self-made man who succeeded at almost everything he did. He had little formal schooling, but managed to make a small fortune before the war, in part from slave-trading. When the war started he enlisted as a private in the 7th Tennessee Cavalry. He eventually used his personal fortune to raise and lead a cavalry battalion of his own. He fought in most of the western campaigns and achieved great success as a cavalry commander, conducting raids that would frustrate the Union time and again. By July 1864 he was a major general and fast becoming a legend.

The South Debated About Where Best to Use Forrest

After the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads Forrest’s troops were dispersed, making for easier resupply. They especially needed new horses. So many men were dismounted and without fresh horses that they were combined into a temporary infantry brigade that would fight on foot until horses could be found.

While Forrest’s troops were resting, a fight was developing over how best to use Forrest and his talents. Concerned with Sherman’s invasion of Georgia, General Joseph Johnston wished to use Forrest to command an “adequate force to destroy the railroad communications of the Federal Army” instead of “waiting for and repelling raids.” Johnston was obviously concerned with his own theater of operations, as was Governor Joseph Brown of Georgia, who wrote Jefferson Davis asking: “Could not Forrest do more now for our cause in Sherman’s rear than anywhere else?” Military logic dictated that if Sherman’s long supply lines could be cut he could be defeated, and one of the greatest threats to the existence of the Confederacy would be removed.

Jefferson Davis had other ideas, and responded that “Forrest’s command is now operating on one of Sherman’s lines of communication and is necessary for other purposes in his present field.” Brown was not satisfied and continued to push Davis to use Forrest to save his state from the Union invasion. Davis angrily responded, telling Brown that he could not dictate the movement of Confederate troops. Forrest would stay in Mississippi.

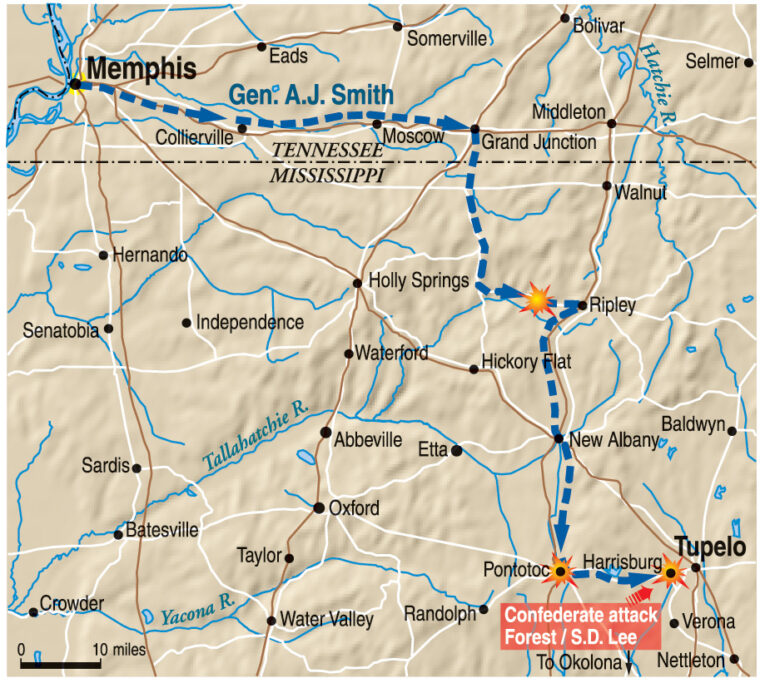

While the debate over Forrest raged and his troops recovered from their exertions, Forrest was still active. Ever vigilant, the Confederate cavalry officer continually sent out reconnaissance patrols to discern his enemy’s intent. Forrest pushed his scouts as far north as he dared, telling them “not only to learn all they can but to see for themselves.” In late June a spy informed Forrest that a large Union force, starting in Memphis, was going to move against Mississippi. The source was so reliable that on June 25 Forrest cabled Lee and explained that he thought the Mobile & Ohio Railroad was the target and to be prepared for an attack. On June 27 he ordered General Philip Roddey, one of his division commanders, to clear his command of all nonessential equipment and personnel and to have his troops ready to move at a moment’s notice. Forrest continued to reunite his command throughout the end of June and the beginning of July. He ordered General James Chalmers’ division from Columbus and reinforced a post at Ripley, Miss. to 600 men. On July 7 this force had a skirmish with a strong Union column and was forced to fall back. The Union advance had begun.

The Union movement started two days earlier, on July 5. Leaving La Grange, Tenn., Smith divided his command and moved out on two parallel roads. The infantry, artillery, and wagons were on one and the cavalry on another, each heading for Forrest’s outpost at Ripley. Smith’s orders for the march showed that he was concerned about the condition of his troops and feared that his numbers would be depleted through straggling. His advance into Mississippi could best be described as cautious. The march orders were exceptionally strict; no one was to fall out if it could be prevented. All canteens were filled to limit the number of men looking for water. Frequent halts to rest, along with numerous roll calls (three a day), were designed to keep men with their commands. The march was hard because of the high heat of summer. Smith also took extra precautions to protect his flanks and rear from surprise by the crafty Forrest.

Torching Most of the Town, Including the Courthouse, Two Churches, and Several Homes

The march went well. Skirmishes at Ripley on the 7th pushed the Confederates back and Smith continued south. Two days later the force crossed the Tallahatchie River and on the 10th arrived outside Pontotoc. The next day a Confederate brigade under General Robert McCulloch was posted in the town with orders to delay the Union advance as long as possible, the point being to allow Forrest and Lee to bring up reserves and prepare for an attack. But Smith deployed a mixed force of infantry and cavalry and pushed the Rebels out of town. Bearing in mind that he should punish the land that kept Forrest replenished, he burned most of the town, including the courthouse, two churches, and several homes.

Next the Union and Confederate forces struggled for Pontotoc, and while this was going on Forrest was making preparations to receive Smith around Okolona, ordering his command to allow the Federals to advance. On the morning of the 12th Smith sent cavalry, backed up by infantry, to scout the road south. These skirmishers had advanced about nine miles down the Okolona Road when they ran into the Confederates. The Rebel pickets fell back and the Union troops soon discovered a strong Confederate force waiting to receive an attack. Upon hearing of it, Smith did not “deem it prudent to attack the position from the front if it could be flanked.”

Thus on the morning of the 13th, Smith, instead of attacking, moved the majority of his command east toward Tupelo, leaving only a token force to distract the Confederates near Okolona. Forrest and Lee were surprised by this change of direction. In the confusion over where to meet the Union troops, the Confederates left a road uncovered, allowing Smith to move without being immediately detected. As soon as Forrest and Lee realized Smith’s movements, they immediately put their forces in pursuit. The result was a running fight on the road to Tupelo with the Confederates assaulting the Federal rear and flank.

The Union cavalry began to reach Tupelo around noon and immediately set about destroying stretches of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. Smith kept marching to catch up to his cavalry, continuing the running fight, while Forrest and Lee worked at bringing up their full force. Several sharp rear-guard actions were fought involving elements of the 7th Kansas Cavalry, U.S. colored troops, and Mower’s Division. During one of these fights the 14th Wisconsin captured the flag of the 19th Mississippi Cavalry. By 9 at night Smith reached Harrisburg, a small town west of Tupelo, and began to set up his defensive line.

Showdown: Lee vs. Forrest

Forrest and Lee now had an important decision to make. They could fight here, outnumbered and forced on the offensive on ground picked by the enemy, or they could allow Smith to continue his march to Tupelo unopposed. Adding to the pressure on Lee was an imminent Federal attack on Mobile, Ala. that required him to dispatch some of the troops under his command to its defense. The Confederate force currently assembled would be the largest one available to oppose Smith. Lee and Forrest decided to fight.

By daylight on the 14th both armies were in position around the tiny hamlet of Harrisburg. The Union forces were in a strong position, made stronger during the night by throwing up crude entrenchments. The lines were drawn up on a ridge bisected by the Tupelo Road. General Mower’s Division was on the right or north side of the road; Colonel Moore’s Division held the left. Mower’s Division was deployed as follows: Colonel Joseph Wood’s Brigade was adjacent to the road, with Colonel Lyman Ward and Colonel William McMillen to its right. Colonel Alexander Wilkins’ Brigade was in reserve. South of the road, Colonel Charles Murray’s Brigade was positioned on the division’s right followed by Colonel Edward Wolf’s Brigade and Colonel Edward Bouton’s Brigade of colored troops on the extreme left. Colonel James Gilbert’s Brigade was assigned a position in the rear to protect the trains. The ridge dominated the surrounding terrain. The nearest patch of woods was 200 yards from the Union position; otherwise there was nearly a mile of open ground between the Union and Confederate forces.

The Rebels’ line roughly paralleled the Union position. On the far right lay Roddey’s two brigades. Brigadier General Abraham Buford’s Division held the area around the Tupelo Road with brigades commanded by Colonel Edward Crossland and Colonel Hinchie Mabry; Colonel Tyree Bell’s Brigade was held in reserve behind Mabry. Chal- mers’ Division lay a short distance behind the first line in reserve, and Brig. Gen. H.B. Lyon’s infantry in a third line behind them. The 6,000 Confederates were outnumbered almost two to one by the roughly 11,000 Union troops.

There was a significant amount of ambivalence in the Confederate high command on the 14th. Forrest was feeling ill and asked Lee to assume full command of the assembled forces. Lee was not enthusiastic about taking command himself. He knew that the odds were very much against his troops. After the war, Lee said that because of Forrest’s recent victory at Brice’s Crossroads, he insisted on “[Forrest] commanding the field, but he said no; that the responsibility was too great, and that his superior in rank should assume and exercise the command; that he considered the Confederate troops inadequate to defeat Smith.” Perhaps shifting the blame for a defeat he saw coming was as much a motivator for Forrest as military protocol.

The plan of battle was simple: Lee ordered Forrest to send Roddey to “swing the right around upon the enemy’s left.” This move would hopefully wrest the Federals out of their trenches and allow Buford’s Division to attack them from the west. Before Forrest could order Roddey forward, however, the Kentuckians under Crossland attacked.

The First Brigade Sprang to Their Feet, and, With a Yell Like That of Demons, Rushed Forward…

At 7 am Crossland’s and Mabry’s Brigades advanced toward the Union works. The Confederates were moved forward only to expel Union skirmishers from a patch of woods. Crossland reported, “I drove in the enemy’s line of skirmishers, and when within 500 yards discovered the enemy’s position. Though ordered to move surely and steadily, it was impossible to restrain the ardor of my men.” Crossland’s Brigade attacked across the field alone and unsupported.

The Kentucky troops were headed toward Murray’s Brigade of the 3rd Division. Colonel Moore, the 3rd Division commander, later reported: “The enemy were permitted to advance in solid columns upon our line through an open field. Our lines being concealed from their view by the brow of the hill, we were not discovered until the enemy had reached a point about twenty paces distant when the troops of the First Brigade … sprang to their feet, and, with a yell like that of demons, rushed forward, pouring into the ranks of the advancing foe a desperate volley of musketry.” The advancing Confederates were brought to a sudden halt. Major Thomas Tate of the 12th Kentucky Cavalry (CSA) called the fire “the most destructive I ever saw.” Colonel Crossland said his troops’ “ranks were decimated; they were literally mowed down. Some of my best officers were either killed or wounded.” The Kentucky troops were forced back in confusion.

Adding to the Kentucky Brigade’s problems, Colonel Murray counterattacked. Colonel James Kinney of the 119th Illinois recalled: “The first volley given by my line caused them to halt, turn back at the double-quick, while we followed, pouring in a murderous fire as we advanced, and covering the ground with dead and wounded in our front.” After pursuing the Confederates to the “foot of the hill in front of our position,” the Union troops returned to their original line and continued to exchange a deadly fire of musketry for the next two hours.

The Kentucky Brigade was still in a desperate state of confusion as it returned to its original line. Forrest himself had “seized their colors, and after a short appeal ordered them to form a new line.” Seeing the intense fire inflicted upon these troops, Forrest decided against advancing Roddey’s Division. Crossland reported the loss of about 300 men out of a total of nearly 800. The 8th Kentucky lost 55 of 115 engaged, and the 3rd Kentucky lost 92 of 145 men on the field.

As the Kentucky troops were falling back, Mabry’s and Bell’s Brigades advanced toward the Union lines. The day was turning hot, and men began to fall out of the ranks from the heat. They approached General Mower’s Division “in three lines, at the same time opening with about seven pieces of artillery. At first their lines could be distinguished separately, but as they advanced they lost all semblance of lines and the attack resembled a mob of huge magnitude,” General Smith remembered. “They were allowed to approach, yelling and howling like Comanches, to within canister range, when the batteries of the First Division opened upon them.” As soon as they approached to within 300 yards of the Federals, “a most terrific fire of small arms was opened.”

Mabry’s line quickly collapsed. Between the heat and the intense fire from the Federals, Mabry reported his brigade was “almost like a line of skirmishers.” Mabry ordered his troops to lie down in a hollow and open fire. Bell’s Brigade now moved to the attack. The results were the same. After approaching to within 75 yards of the Union line, they were forced to fall back.

Rucker’s Brigade Ran for 2000 Yards Under Fire in Plain View of the Enemy

Chalmers’ Division, meanwhile, was ordered to support the first line. Confusion once again overcame the Confederate forces. Chalmers received three separate orders. Forrest told him to support Roddey’s Division, Lee to support Mabry, and Buford to relieve his forces in the center. At first, following his immediate superior—Forrest—Chalmers ordered the division to the right. But as it began to move toward Roddey, Lee arrived and ordered it to turn around and join the fight along the Tupelo Road.

Chalmers left McCulloch’s Brigade in reserve and rushed Colonel E.W. Rucker to the scene of the fighting. By the time the brigade arrived, however, Crossland, Mabry, and Bell had all been brutally repulsed. Now Rucker’s Brigade attempted to storm the Union works. “We passed over plowed ground and through a corn-field, in full view of the enemy, for 2,000 yards, under fire of three pieces of artillery and small-arms from the enemy.… Before we reached the position to charge many of the men fainted from exhaustion and the remainder were unable to drive the enemy from his position.” Rucker’s men were forced back and took a position on the left of Mabry’s and Bell’s Brigades.

Fighting continued for several hours. Mower, realizing that the Confederates were not going to attempt another attack, ordered his division to counterattack the Southerners. Woods reported that “our whole brigade charged the enemy, driving him from the field and getting possession of his killed and wounded, who lay thick upon the field.” Colonel Ward, commanding the 4th Brigade, recalled that “at 10:30 o’clock I was directed to make a charge with my brigade … advancing nearly half a mile and driving the enemy in confusion.” Mower’s Division held its advanced position for a short time and then returned to its original line. At least 270 Confederate dead lay in front of the division’s lines.

Mower’s counterattack marked the end of the most serious fighting. The intense heat of the midday sun worsened the situation for the beaten Confederate troops.

During the night, Union troops began to torch several of Harrisburg’s buildings. Chalmers ordered McCulloch’s Brigade to advance but still found the enemy position “strongly taken.” Instead, Chalmers contented himself with ordering some artillery up and firing on the Union positions, now silhouetted by the fires from the buildings. After some skirmishing, McCulloch’s Brigade was withdrawn.

At about 10 o’clock in the evening Forrest ordered Rucker’s Brigade to probe the Federal left flank near the Verona Road, which initially forced Wolf’s Brigade to fall back. The Union 3rd Division was quick to react, and Gilbert’s and Bouton’s Brigades were quickly rushed to the scene. Forrest recalled that the Federals “opened upon me one of the heaviest fires I have heard during the war.… There was [an] unceasing roar of small-arms, and his whole line was lighted up by a continuous stream of fire.” Although both sides claimed that the other had suffered severe casualties, the gunfire was generally ineffectual. Rucker’s Brigade was withdrawn with no one killed.

On the morning of the 15th, Smith had only about a day’s rations left, much of the bread having spoiled. So the Union general decided that he would return to his base and ordered Grierson to destroy the railroad for about five miles each way. He had the enemy wounded moved into comfortable quarters in Tupelo and left two surgeons with them. Smith left behind about 40 wounded men of his own command. After some ineffectual skirmishing in the morning, he ordered his troops to begin withdrawing at noon.

Forrest meanwhile ordered Buford to advance up the Verona Road and attack the Union left flank. Crossland’s and Bell’s Brigades attacked and succeeded in driving the Union skirmishers to a line of timber where the Northerners were reinforced by several regiments, including the 61st and 68th U.S. Colored Infantry. By this time, Buford’s forces were exhausted by the fighting and the heat.

The Union withdrawal continued unmolested until Forrest and Lee became aware of the empty trenches to their front, and a general advance was ordered. Buford’s Division was again in the lead and came into contact with three regiments of cavalry under Grierson near Old Town Creek. Buford unlimbered Rice’s battery while Crossland and Bell advanced. Grierson gradually fell back from position to position until he reached the wagon train.

After about half an hour of skirmishing, help arrived for the Union cavalry. Colonel William McMillen marched up with his 1,600 men. “I at once formed the [brigade] … and by direction of Brig. Gen. J.A. Mower … charged the enemy.” Gilbert’s Brigade also joined in the counterattack. “The whole line poured in a volley, raised a shout, scaled the fence, and pressed steadily forward in the open field firing as they advanced.” Buford’s Division broke off the engagement, and the Union forces camped safely for the remainder of the evening.

1,326 of 6,000 Soldiers Killed

The clashes on the 15th marked the end of any major engagements of the campaign. Smith withdrew to Ellistown on the 16th and New Albany on the 17th. He marched back into La Grange on the morning of the 21st. The campaign was over.

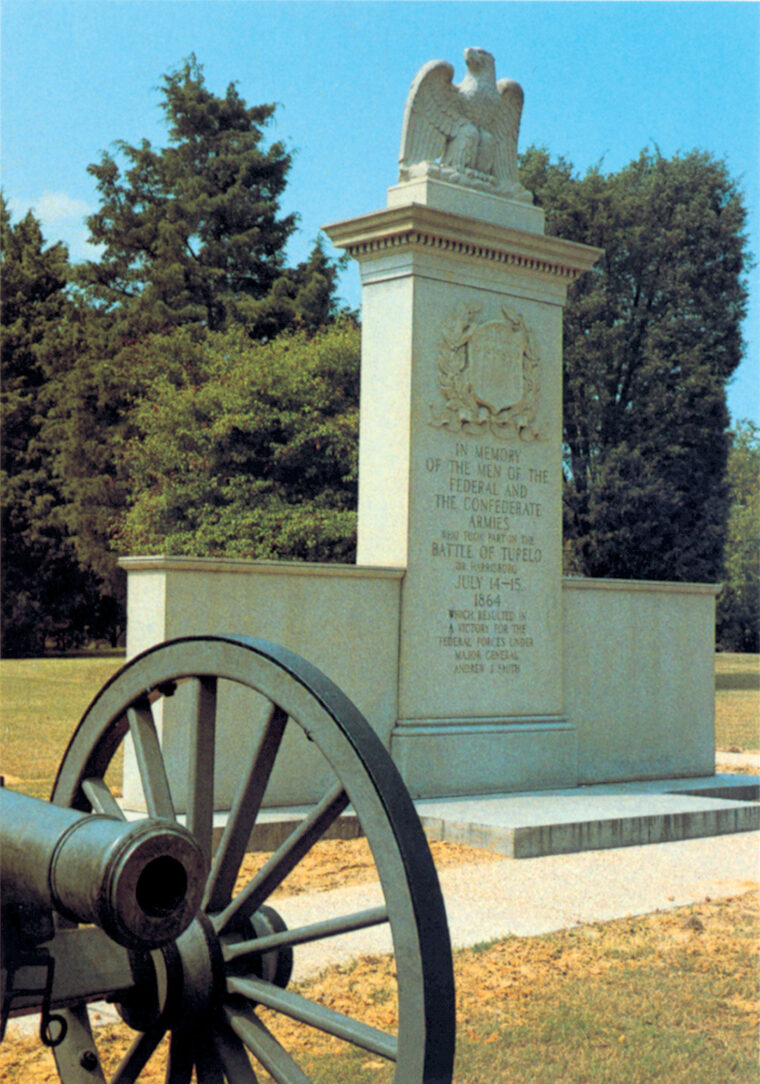

The Confederate forces had taken severe casualties. Forrest reported his losses at 1,326 of approximately 6,000 men engaged. Three brigade commanders, Rucker, McCulloch, and Crossland, were severely wounded, and Forrest himself took a bullet in the foot. More important for the Confederates was the loss of regimental officers. Colonel Isham Harrison and Lt. Col. Thomas Nelson of the 6th Mississippi, Lt. Col. John Cage of the 14th Confederate, Lt. Col. Sherrill of the 7th Kentucky, and Major Robert McCay of the 38th Mississippi lay dead. In Bell’s Brigade, four colonels were wounded. Mabry reported that all of his regimental, and most of his company commanders, were wounded.

Smith’s forces suffered significantly less. Six hundred and seventy-four Union troops were reported killed, wounded, or captured. Of all the Union brigade or regimental commanders, only Colonel Alexander Wilkins of the 1st Division was killed.

Thus one might well judge Smith’s expedition a success. He was able to inflict a significant defeat on Forrest and remove the aura of invulnerability that swirled around his name. Many of Forrest’s units were badly hurt. In addition to the increasingly difficult manpower resource, the high number of veteran-officer casualties significantly denigrated Forrest’s combat effectiveness, at least in the short run. Smith also prevented Forrest from moving to cut Sherman’s supply line stretching from Tennessee into Georgia, just as Sherman was closing the vise around Atlanta.

But Smith failed to more than temporarily remove Forrest as a threat to Union armies. Just a few weeks after the fight at Harrisburg, Forrest would be causing a great deal of trouble in Tennessee. Later in 1864, he would accompany John Bell Hood’s Army on its Nashville campaign. The only thing that would stop Nathan Bedford Forrest would be the final collapse of the Confederacy itself.

Good article. Very descriptive. One suggestion is to put a small caption around the pictures so the reader knows who the individuals are. Reading on an iPhone is hard to tell.