By Al Hemingway

Peering through his binoculars, Vice Adm. Chuichi Nagumo was in awe of the nearly 800 ships from Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance’s 5th Fleet. Just three years before he had led the carrier force at the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor that initiated hostilities between Japan and the United States. But this was no time to gloat over past victories. As he lowered his glasses, Nagumo realized that the Americans must be stopped here. If the invading forces captured Saipan, their Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers could easily reach Japan itself.

Saipan, about 85 square miles in size, is the southernmost island in the Marianas chain. It was the next important step in the Allied planning to conquer Japan. One of Saipan’s dominating features is Mount Tapotchau, over 1,500 feet high, situated near the center of the island. Also, a ridge runs from the southern end all the way to Mount Marpi at the extreme northern tip. To make things worse, steep cliffs dominate the region and a plateau is located in the southern area.

“Saipan combined everything that the Americans had learned to hate about fighting the Japanese,” wrote historian Brian Blodgett in his paper “The Invasion of Saipan.” “The island was comprised of varied landmasses with swamps, sugarcane fields, jungle-covered mountains, and steep ravines.”

American forces had their work cut out for them.

And the Japanese had not been idle. They had been fortifying the island’s defenses since the mid-1930s. The military had constructed airfields, barracks, radio direction finders, artillery positions, lookout stations, and ammunition dumps. On the southern tip of Saipan was Aslito Airfield, the major airstrip in the region. Another aerodrome was located at Charan Kanoa on the island’s southwest coast. Tanapag Harbor, on the western coast, near the town of Garapan, also served as a seaplane base. It was also used as a refueling stop and supply station for the Imperial Japanese Navy.

“The Fate of the Japanese Empire Depends on the Result of Your Operation”

Sharing command on Saipan with Nagumo was Lt. Gen. Yoshitsugu Saito. He was in charge of the Army contingent. Even the Japanese prime minister, Hideki Tojo, realized the importance of Saipan when he told Saito: “The fate of the Japanese Empire depends on the result of your operation.” Although in poor health, Saito accepted his fate. He knew it would be a struggle to the death.

Nagumo did not get along with his Army counterpart. Saito was becoming increasingly irritated by the Navy’s failure to eliminate the U.S. submarine threat and blamed Nagumo personally. One-third of all ships were lost to American subs prowling the waters near Saipan. These strained relations did not bode well for the impending battle. Nonetheless, the Japanese garrison on Saipan was prepared to die for the Emperor—and take as many American troops with them as possible. In spite of their differences, both Nagumo and Saito were optimistic. If they could hold the Americans at the beach and fight a delaying action, their massive combined fleet could reach Saipan in time, maul the American naval vessels covering the invasion area, and help Japanese land forces annihilate the invading armies.

Saito’s force defending Saipan consisted of the 31st Army, which included the 43rd Division and the 47th Independent Mixed Brigade. Admiral Nagumo had the 55th Naval Guard Force and the 1st Yokosuka Special Landing Force under his command. Although the U.S. Navy was sinking Japanese troop transports at an alarming rate, the army on Saipan was still formidable; some 30,000 troops were poised to do battle.

In addition, the island’s civilian population, which was a mixture of Japanese, Okinawans, Koreans, Formosans, and the native Chamorros and Kanakas, was pro-Japanese. The majority of the citizens of Saipan hated the Americans as much as the Japanese military, and believed them to be butchers and rapists.

Preliminary bombing of Saipan commenced on June 11. Over 200 bombers and fighters from Task Force 58 went virtually unchecked as they “plastered” Aslito Airfield and Garapan. As the U.S. aircraft casually flew away, leaving behind the burning wreckage of over 50 aircraft strewn about the airstrip, one disillusioned enemy observer later wrote in his diary: “Now begins our cave life.

16-Inch Shells Ripped Into the Landscape

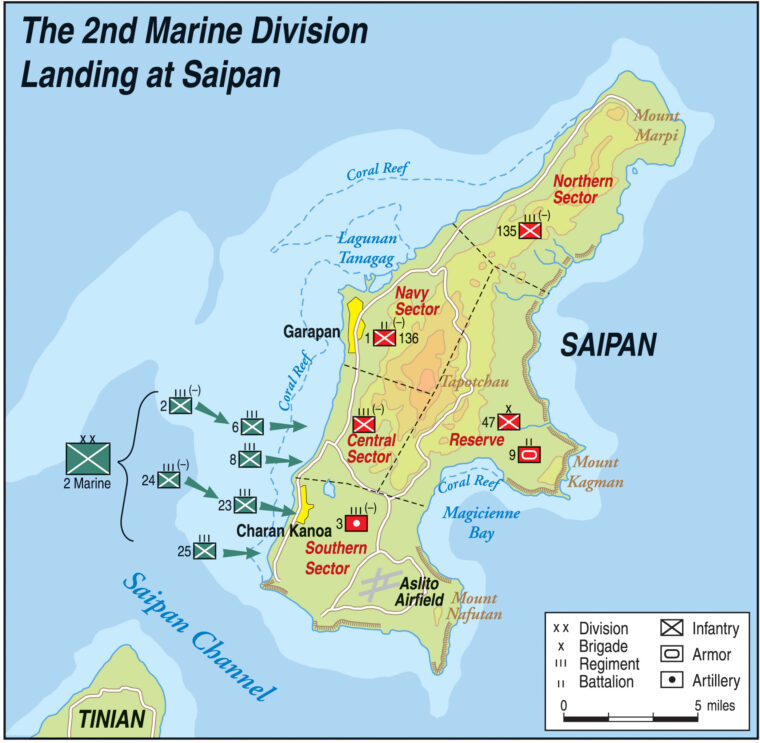

As the Japanese were hurriedly preparing Saipan’s defenses, Spruance was busy as well. He had given the assignment of seizing Saipan to the crusty Marine Lt. Gen. Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith. Smith tapped the 2nd Marine Division of Tarawa fame led by Maj. Gen. Thomas E. “Terrible Tommy” Watson. He also selected the 4th Marine Division under Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt and the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division commanded by Maj. Gen. Ralph C. Smith. For additional punch, Smith had the U.S. Army’s XXIV Corps Artillery, headed by Brig. Gen. Arthur M. Harper. Most of the Leathernecks in both divisions had experienced combat on Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Kwajalein, or Eniwetok. On the other hand, the majority of the Army personnel had not experienced their first taste of war; however, that would soon change in the days to come.

On June 13, Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher’s battleships of Task Force 58 let loose an awesome barrage upon the island. Sixteen-inch shells from seven new battleships ripped into the landscape, reducing buildings and other structures to masses of smoldering rubble. For the next 10 hours the battlewagons fired more than 15,000 rounds of 16-inch and 5-inch shells. However, because the vessels were so far offshore, their bombardment did not do as much damage as first thought. The smokestack at the sugar mill at Charan Kanoa was left intact. During the fighting a few days later, an enemy forward observer climbed to the top and used it quite effectively.

The following day, the older, more experienced battlewagons, such as the Tennessee and California, let loose their pounding upon the Japanese. Accompanied by cruisers and destroyers, the armada commenced firing. However, two days of incessant bombing still did not silence many of the Japanese beach defenses, which were still operational when the assault troops hit the beach.

A Menacing Island Paradise

As the Navy belched round after round at the island, the Japanese initiated “A-Go,” a plan to halt the American advance in the Pacific. Admiral Soemu Toyoda’s Combined Fleet steamed toward Saipan to crush U.S. forces. “The fate of the Empire rests on this one battle,” remarked Toyoda.

In the predawn hours of June 15, the U.S. attacking force was poised a few miles off the beaches. Time-Life correspondent Robert Sherrod later wrote: “[Saipan] was a shadowy land mass, purple against the dim horizon. Set against the reddish tint of the morning sun, it seemed unbelievable that this island paradise could prove to be so menacing.”

Without warning, the massive flotilla offshore suddenly sprung to life with a thunderous barrage. At 0700 the firing ceased and 51 scout bombers and 54 torpedo bombers roared toward the beaches to further harass the defenders. This bombing and strafing run lasted for 30 minutes. As the planes streaked away, the ships once again commenced their deafening bombardment. With all the naval gunfire and air strikes, Saipan was barely visible from the transports amid the columns of thick, black smoke swirling upward.

After a feint in the north, the invasion force soon headed for the landing beaches located on the southwest coast. Covering a four-mile area, the 2nd Marine Division was on the left and the 4th Marine Division on the right flank. Several dozen LCI (Landing Craft, Infantry) gunboats fired rockets and strafed the shore with 20mm and 40mm guns. Following them were over a hundred amphibian tractors, or “amtracs,” equipped with 75mm howitzers and machine guns. Half the vehicles were U.S. Army and the remainder belonged to the Marines. Behind them rode the assault troops—about 700 regular amtracs—ready to hit the beach.

Punishing Fire Rained Down On the Marines

Japanese artillery shells soon sent huge geysers of water skyward. Marines ducked for cover as some of the enemy rounds began to find their mark. On Red Beach 2, Lt. Col. William K. Jones narrowly missed death. He was sitting on an ammunition crate when suddenly a shell burst overhead. At first Jones thought he was wounded when he saw blood on his hand. Looking around he also noticed a gaping hole in the side of the tractor near which he had just been standing. Turning to his right he saw where the blood had come from. Two Marines were bleeding profusely—both had been beheaded by the shell that had caused the hole in the vehicle.

To the south, on Green Beach, the 2nd and 8th Marine Regiments were also finding the going tough. Lieutenant Colonel Ray Murray, leading the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines, soon fell from wounds. Also, Lt. Col. Jim Crowe, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines, was also a casualty when he was shot in the chest. As two medical personnel ran to assist Crowe, a mortar shell exploded nearby, killing both of them and wounding Crowe again.

Problems soon developed. Because of the heavy Japanese shelling from Afetna Point and an unusually strong northerly current, elements of the 2nd Marine Division had landed farther north than anticipated. This caused confusion and overcrowding of men wading ashore at the point where Green Beach 1 and Red Beach 3 were located. Soon, a large gap between the two divisions developed.

On Yellow and Blue Beaches, the 4th Marine Division was also running into stiff opposition. Particularly hardest hit was the 1st Battalion, 25th Marines on Yellow Beach 1. The Leathernecks were forced to “hug the beach” as enemy automatic weapons and mortar fire rained down upon them. Also, pointing down at the Marines were 16 105mm, 30 75mm, and eight 150mm howitzers. One thing in favor of the Leathernecks was the fact that the Japanese did not concentrate their firepower. Most batteries were firing independently of each other.

“The Japanese couldn’t hit the side of a barn with artillery pointblank,” Pfc. Sam Stillwagon later remarked. “Now mortars, that’s something else. Give them a mortar and they could put it in your hip pocket.” Despite Stillwagon’s condemnation of Japanese marksmanship, Marine casualties were mounting as the day wore on.

Saito Escapes Death… But Just Barely

To silence the Japanese, naval gunfire was called in. Also, fighter planes strafed and bombed suspected Japanese gun emplacements. Army amphibious tractors carrying the 2nd Battalion, 25th Marines soon appeared and the infantrymen quickly disembarked to join in the fight. Later, one Marine officer praised the efforts of the Army amtracs that led the attack. “They took more than their share of punishment and diverted enemy attention from the tractors carrying troops,” he said.

Meanwhile, Nagumo was observing the ongoing battle from a distant hilltop. As he marveled at the massive U.S. naval display before him, he noticed that several of the battleships being used in the invasion had been sunk or badly damaged at Pearl Harbor by his carrier strike force. The Americans had obviously repaired them or built new ships. How ironic, he thought. Nonetheless, the Japanese officer beamed with pride as he pointed out this fact to one of his staff officers.

Saito narrowly escaped death that first day. As he was speaking at a conference with his officers, an errant shell found its mark. Nearly half the group was killed in the explosion, but Saito miraculously survived the blast. Although incoherent and dazed, he quickly regained his faculties and resumed command of the Army.

In the 4th Marine Division’s sector was the burned-out town of Charan Kanoa. In his book A Special Valor: The U.S. Marines in the Pacific War, author Richard Wheeler describes the terrain. “The undulating coastal lowlands the Marines were facing were made up largely of farms, cane fields, brush patches, and woodlands. The preliminary bombardment had torn up the terrain and blackened it with fires, and most of the farmhouses and their utility buildings had been destroyed or damaged. This area had few heavy fortifications but was amply furnished with mortar and machine gun positions, together with riflemen in ruined buildings, in trenches, in clumps of brush, and behind rises in the fields. The terrain was well suited to defense. Once again the Marines, although superior in numbers and firepower, knew the terrifying disadvantage of having to advance in the open against a concealed and deadly enemy. They had to initiate each encounter by pitting their flesh against steel.”

Too Tired to Remember Their Names

Lieutenant Colonel John J. Cosgrove’s 3rd Battalion, 23rd Marines were soon advancing along Charan Kanoa’s death ground. The riflemen came under intense shelling as they moved forward. “One man was brought in with his leg almost blown off between the hip and knee,” recalled Marine Combat Correspondent Sergeant David Dempsey. “The doctor amputated without removing him from the stretcher.” Some Marines suffered from combat fatigue. “They hid behind trees,” Dempsey continued. “And cowered at each new shell burst. Some could not remember their names.”

One of the young Marines wounded during the fight for Saipan would later become a Hollywood legend—actor Lee Marvin. Marvin came ashore with Company I, 3rd Battalion, 23rd Marines on Yellow Beach 2. “During a firefight there are two parts of the body the enemy can pretty much see while hugging the deck,” he recalled during an interview in Leatherneck magazine years later, “the head and the butt. If you present one, you get killed. If you raise the other, you get shot in the butt. I got shot through the wallet.” The Japanese bullet had severed Marvin’s sciatic nerve. It took over a year in various hospitals before he fully recovered from his wound. Although narrowly escaping death, the Academy Award-winning actor said jokingly: “I received my Purple Heart in a hospital on Guadalcanal. I got a permanent scar on my keister and a check once a month for life.”

Meanwhile, in the 6th Marines sector, the three battalions pushed forward. At noon, three Japanese tanks lumbered into the lines and hit the flanks of the 1st and 2nd Battalions. Soon, Companies A and G were bearing the brunt of the assault. Marines armed with rocket launchers quickly disposed of the enemy armor, and the infantrymen continued their northerly drive.

As dusk approached, all movement ceased and the obligatory order was given to dig in for the night. One private was heard to say: “My father always told me that if I didn’t finish high school I’d end up digging ditches!”

“Tell the Colonel the Kitchen Sink is Here!”

As the Leathernecks ate cold C-rations, each kept a wary eye out for the cunning Japanese. Every man knew nightfall would bring the inevitable Japanese Banzai attack. One officer instructed his platoon to keep vigilant because the Japanese would hit their lines with everything “including the kitchen sink.”

Just after midnight, the all-too-familiar sound of infantry and tanks could be heard coming from Garapan. The enemy was chanting and hollering, obviously drunk on sake as they pressed ahead.

Suddenly, a tank appeared. It came to a halt and the turret popped open. A soldier emerged from the vehicle and put a bugle to his lips to sound the charge. Amid the bloodcurdling screams of Banzai, the horde rushed the perimeter. One Marine private yelled: “Tell the colonel the kitchen sink is here!”

As the enemy onslaught came closer, the riflemen poured volley after volley of fire into their ranks. The broadside was so fierce the Japanese never breached their lines.

At dawn the Leathernecks ventured forward to survey the scene. Nearly 700 enemy soldiers were killed, and their mangled and twisted bodies littered the battlefield. The Marines also came upon the tank that had signaled the charge. The dead bugler was slumped over the turret. One M-1 Garand round had found its mark, going straight into the instrument’s stem and killing the man.

2,000 Marines Dead or Wounded

Despite numerous probes during the night, including one where Saipan’s civilians were in the forefront of the assault concealing the Japanese infantry, the Marines held their ground. They had established a beachhead 10,000 yards long and approximately 1,000 yards deep. But it had come at a steep price. Over 2,000 Marines were either killed or wounded.

Saito, still thinking the landings were a feint, did not order any coordinated counterattacks against the Americans. He did not exploit the large opening between the two divisions, and his local commanders struck the invading forces piecemeal. He had missed his greatest opportunity to deal a serious blow to the Marines.

Also during the evening, Spruance visited Rear Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner and General Holland Smith on Kelly’s flagship Rocky Mount. Spruance informed them that the Japanese Combined Fleet was steaming toward the Marianas and should arrive in 48 hours to do battle. He also instructed them to finish their unloading operations so he could get his transports out of harm’s way and intercept the enemy flotilla.

Nodding in agreement, Smith gave the order to land the Army’s 27th Division. However, the lead unit, 165th Regiment, was “literally thrown onto the beaches” after a “snafu” developed between the Army and Navy on the location of the landing site. Nonetheless, they came ashore and were finally situated to the right of the 4th Marine Division the following morning. Following them, the 105th Regiment came ashore on Blue Beach and the 106th Infantry landed several days later.

McCard Dismantled the Tank’s Machine Guns & Killed 16 Enemy Soldiers

The next day, the 2nd Marine Division stepped off to attack on the left flank while the 4th did the same on the right. As the 1st Battalion, 25th Marines edged into the firefight, tanks were brought forward to assist them. One armored vehicle, led by Gunnery Sgt. Robert H. McCard, was struck and immobilized by a Japanese 75mm howitzer. When the crew was pinned down, McCard told them to run to safety as he covered them. He then dismantled one of the tank’s machine guns and personally killed 16 enemy soldiers. He was killed while performing this heroic act of bravery and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

The Leathernecks gained small footholds, but the Japanese fought back relentlessly. As evening neared, all hands prepared their night positions. At 0345 enemy tanks rushed the Company B, 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines portion of the line. Mortars and 37mm pack howitzers did little to halt their advance. Men used rocket launchers and antitank grenade launchers with armor-piercing shells to halt the enemy juggernaut. One intrepid Marine, Pfc. Herbert J. Hodges, stopped seven tanks with just seven rounds. When it was over, 24 tanks were laid to waste along with 700 Japanese riflemen. It had been the biggest tank battle of the Pacific War up to that time.

As the Marines moved northward, the 105th and 165th Infantry Regiments joined forces to overrun Aslito Airfield. By mid-morning on June 18, the airstrip was in American hands. The following day, the GIs made their way toward Nafutan Point on the island’s extreme southeastern tip. Leading the assault was the 1st Battalion, 105th Infantry commanded by Lt. Col. William J. O’Brien, a cocky little rooster of a man.

O’Brien pressed his men onward. His plan was to outflank the enemy on Ridge 300 near Nafutan Point. On June 21, the infantry commenced the attack with three tanks in support. O’Brien was everywhere during the battle. At one point, when one tank was inadvertently firing on its own men, he leaped on the vehicle and beat on the turret with his pistol. The tank finally halted, and O’Brien rectified the situation. Amazingly, the senior officer stayed perched on the tank throughout the firefight.

445 Japanese Pilots Lost; Most Were Teenagers

With the southern part of Saipan in American hands, Holland Smith was now poised to begin his major thrust to seize the entire island. His first objective was Mount Tapotchau in the center. Also, good news had arrived. Spruance’s ships had dealt the Japanese Combined Fleet a disastrous blow in the Battle of the Philippine Sea near Guam. Three enemy carriers plus numerous other ships had been sunk. Also, the Japanese had suffered horrendous casualties when 476 planes were shot out of the sky, and 445 of their pilots, although mostly inexperienced teenagers, were killed. This lopsided victory would soon be dubbed the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.”

Now with no hope of rescue, Saito and Nagumo braced themselves for the inevitable conclusion. However, the enemy was still determined to kill as many Americans as possible before giving their lives for the Emperor. As one young soldier wrote in his journal: “I will take out my sword and slash, slash, slash at him as long as I last.…”

Holland Smith conferred with General Ralph Smith and praised Smith’s soldiers, while also informing him of the impending assault on the mountain. Ralph Smith’s GIs were to move into position in the center of the line for a three-division attack. When “Howlin’ Mad” Smith left, Ralph Smith was elated and mentioned to another officer that the Army and Marines had “perfect teamwork.” Unfortunately, this euphoria would soon disintegrate and lead to one of the biggest controversies of the war between the two services.

The situation began to fall apart when “Howlin’ Mad” Smith had to wait for the Army to complete its seizure of Nafutan Point before assaulting Tapotchau. The infantrymen were making no real progress against the “holed-up” enemy troops, and the Marine general was becoming increasingly irritated. Even the official U.S. Army history would not be favorable: “Units repeatedly withdrew from advanced positions to their previous night’s bivouac, and repeatedly yielded ground they had gained.”

Disgusted, the Marine commander pulled the 27th Division from Nafutan and ordered it to drive the Japanese off the mountain itself. In the meantime, the 2nd Marine Division inched its way to the northeast and the 4th Division headed eastward to capture Kagman Peninsula. The 27th and the 2nd had the worst going. In addition to the mountains and hills, there was a valley inundated with steep cliffs which the Japanese had laced with gun emplacements. The men who fought there soon began calling the area “Death Valley” and “Purple Heart Ridge.”

This labyrinth of caves, slit trenches, and ravines did not impress “Terrible Tommy” Watson, however. The 2nd Marine Division commander screamed during one firefight: “There’s not a goddamn thing up on that hill but some Japs with machine guns and mortars. Now get the hell up there and get them!”

An Unprecedented Relief of Command

On June 23, the Leatherneck divisions proceeded to attack the enemy fortifications. As 18 batteries of artillery sprung into action, Turner’s ships offshore joined in the shelling to soften the Japanese bulwarks. The 27th Division failed to link up with the rest of the assault troops because one of its regiments got lost on its way to the front.

For two days the Americans struck the enemy positions. The Marines had gained ground, but the GIs had troublesome terrain in the center. Because of this, the attacking units now resembled a large “U” with the Leathernecks’ flanks dangerously exposed.

“Howlin’ Mad” Smith had had enough. He discussed the problem with Admirals Turner and Spruance and told them he wanted to relieve General Ralph Smith of command. This was unheard of—a Marine general was relieving an Army general. Both admirals acquiesced to Smith’s decision. Ralph Smith was replaced with Maj. Gen. Sanderford Jarman. On June 28, Maj. Gen. George W. Griner arrived from Hawaii to take permanent charge of the division.

Repercussions from Holland Smith’s decision reached all the way back to Washington, DC; however, the irascible general refused to yield. “I don’t care what they do to me,” he confessed. “I’ll be 63 years old next April and I’ll retire anytime after that.”

Some historians have argued that the Marine officer was not justified in removing Ralph Smith from command. The 27th Division on Saipan had extremely difficult ground to cover. Certainly the GIs had fought as bravely as the Marines had on the island. However, someone had to be accountable, and Ralph Smith was the unfortunate one. As the “battle of the Smiths” went on, the attack on Saipan continued. And more men—Marines as well as soldiers—would die capturing the island.

Artillery Shells Deafen the Marines & Fling Them Skyward

On the evening of June 26, the enemy attempted a futile Banzai attack in the southern sector. A large group of about 500 made its way through the Army lines and struck the airstrip. The enterprising Japanese destroyed one P-47 fighter and damaged several others. Rear echelon units soon surrounded the Japanese, some hidden in caves, and finished them off. Not wanting to surrender, the survivors committed hara kiri, ritual suicide. With that, all organized fighting in the southern region was over.

All attention was now to the north. At a place dubbed “Obie’s Ridge,” the 105th Infantry surprised the enemy. Led by the feisty Colonel O’Brien, the soldiers confiscated a 75mm howitzer and five Nambu machine guns.

Meanwhile, on July 2, the 2nd and 6th Marines swept over Sugar Loaf Hill, a stone mountain that had been hollowed into a fortress. As the Leathernecks assaulted this enclave, they encountered heavy mortar and automatic weapon fire. Grenades were hurled into cave openings. Artillery shells literally picked men up and flung them back to the ground, shattering eardrums in the process.

Utilizing flamethrowers, satchel charges, and hand grenades the riflemen seized the hill. As they overran their objective, the 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines linked up with the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines at Garapan and Tanapag Harbor on the coast. As the weary Leathernecks cooled themselves off in the refreshing seawater, one Marine suddenly cried out: “Son of a bitch! Tomorrow is the 4th of July!”

“No Matter What Else Happens, Keep Going”

As the 2nd Marine Division was enjoying a well-deserved rest, the 4th Marine Division was moving on Marpi Point. In addition, the 27th Infantry Division pushed northward to eliminate the remainder of the Japanese defenders. The 2nd Battalion, 105th Infantry, which had been at Nafutan Point, was released and hooked up with the rest of the regiment. O’Brien continued to advance. “Keep going,” he shouted. “No matter what else happens, keep going.”

As the sun set on July 6, the 1st Battalion, 105th Infantry dug in for the night on the east side of a railroad track. The 2nd Battalion had encamped on the west side. O’Brien saw that a large opening had developed in the lines and quickly asked for additional troops to plug the breach in the perimeter. When none were forthcoming, he had all his antitank guns and heavy automatic weapons cover the area in the event of a Japanese Banzai assault. The enemy would not disappoint him.

Realizing the end was near, Saito issued his last command to his men. It read in part: “We must utilize this opportunity to exalt true Japanese manhood. I will advance with those who remain to deliver still another blow to the American Devils, and leave my bones on Saipan as a bulwark of the Pacific.… Here I pray with you for the eternal life of the Emperor and the welfare of our country, and I advance to seek the enemy. Follow me!”

Defeat and Seppuku

However, Saito was so frail he never accompanied his soldiers on their last major assault. Instead, he and Nagumo walked to another cave with two staff officers. After they bowed to each other, and in the direction of their homeland and the Emperor, they both sat down. As they plunged their samurai swords into their abdomens, the two aides put a bullet in each of their heads.

As the two leaders of the Japanese garrison on Saipan were committing ceremonial suicide, 3,000 of their followers were poised to strike one last blow.

In the predawn hours of July 7, every available Japanese soldier and sailor gathered at the northern end of the island near Makunsha, a village on the west coast. Even the walking wounded, some hobbling on crutches, joined in the attack. Some were armed with just knives or bayonets tied to the end of long poles. Drinking sake to bolster their courage, the soldiers were ready to begin one of the biggest Banzai charges of the Pacific War.

The formation split into three groups. One headed for the 3rd Battalion, 105th Infantry, located on the high ground, with the remainder of the force heading for the large gap between the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 105th Infantry.

A Melee of Exceptional Barbarity

Just as the sun rose, the GIs were stunned to see thousands of screaming Japanese hurl themselves at their perimeters. Vastly outnumbered, the soldiers fought bravely. Major Edward McCarthy, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, remarked later: “They just kept coming and coming. It didn’t matter if you shot one; five more would take his place.”

“The melee was one of exceptional barbarity,” wrote Richard Wheeler. “Hand grenade fragments ruptured flesh and fractured bones. Bayonets on Garand rifles clattered against improvised spears as one or the other was thrust home. Skillfully wielded swords lopped off heads, sliced away shoulders, and bared intestines. There was kicking, fist-fighting, clawing, and incidents of strangulation. Men on both sides fell by scores, and the ground became a patchwork of bloodstains.”

The indomitable O’Brien raced along the perimeter among his men screaming at the top of his lungs and urging them on. “Don’t give them a damn inch,” he hollered. Clutching a .45-caliber pistol in each hand, he refused to surrender his ground. When his ammunition was depleted, he commandeered an M-1 rifle and emptied the clip at the enemy. He then leaped atop a jeep and began firing a .50-caliber machine gun that was mounted on it. In all, he killed 30 of the enemy. Unfortunately, a crowd of Japanese surrounded him and struck him down. For his outstanding bravery, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Despite their defiant stand, the soldiers could not hold back the hordes smashing into their positions. The Japanese force poured through the Army’s lines and slammed into the perimeter of the 3rd and 4th Battalions, 10th Marines. The official history states: “The gunners could not set the fuses fast enough to fire so they lowered the muzzles and produced ricochet fire by bouncing the shells off the ground. Those not manning the guns fired every type of weapon they could get their hands on.”

The 6th and 8th Marines were pulled out of reserve and immediately swung into action to reinforce the beleaguered soldiers and Marines. Soon the enemy drive fizzled, but the 105th Infantry had suffered horrific losses. When the battle was finally over, one Marine commented: “You could hardly take a step without walking on a body.”

For the next several days mopping-up operations continued. Pockets of cave-dwelling Japanese troops were eliminated. One Marine officer said it was “just like killing rats.” All organized resistance was virtually gone by July 9, and Saipan was declared secured.

However, on Marpi Point, an event occurred that sickened even the most battle-hardened soldier or Marine. The island’s civilians, convinced by the Japanese that there would be U.S. reprisals, began to hurl themselves into the ocean from the cliffs. So many committed suicide from this point that American troops soon began to call it Suicide Cliffs. Mothers jumped with infants in their arms. Entire families killed themselves by holding grenades to their stomachs. Women crushed babies’ heads by slamming them against the rocks.

“Hell Is Upon Us”

American interpreters used bullhorns to attempt to persuade the civilians that no harm would come to them, and to cease the senseless slaughter. Japanese snipers shot those who hesitated to fling themselves from the sheer cliffs to the coral rocks below. It was a ghastly sight as hundreds of bodies floated in the ocean and washed ashore. No one knows the exact count of the dead, but it was later estimated that 15,000 civilians lost their lives during the battle.

Time magazine stated that Saipan was “one of the bloodiest battles in U.S. military annals.” In the end, U.S. casualties were 16,525 dead, wounded, and missing. Of this, nearly 13,000 were Marines and over 3,500 were soldiers.

“Saipan was probably the worst operation I made in World War II—or the Korean Conflict for that matter,” said 1st Lt. Albert Tidwell, a platoon commander with the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines. “For the first 14 days I didn’t have the time nor the water to wash my feet.”

However, despite the horrors of the struggle, the seizure of Saipan ensured that the Americans had a base from which to launch air strikes at the Japanese mainland. Those who were killed did not die in vain.

Repercussions from the fighting on Saipan reverberated back to Japan. The defeat of their army caused Premier Hideki Tojo and his entire cabinet to resign. Emperor Hirohito and other members of the military were visibly shaken. One senior officer exclaimed: ”Hell is upon us.”

Those prophetic words would soon become a nightmarish reality. As one Marine historian would write, Saipan was “The Beginning of the End” for the Japanese Empire.

1. Gunnery Sgt. McCard wouldn’t have able to shoot anyone with a “dismantled” machine gun. He would have ‘dismounted’ the gun from the tank, in order to employ it in an off-hand manner.

2. The Japanese tanks, stopped by Co. B/1Btn./2 Regt., would have been ‘laid waste’, as opposed to “laid to waste.”

Super article enjoyed the facts. We should have A bombed all og of japan period.

Super article enjoyed the facts. We should have A bombed all of japan period.