By Flint Whitlock

By the autumn of 1944, German resistance in the West was quickly crumbling as the British and Americans approached the German border 233 days ahead of schedule. Two army groups, the 21st, commanded by Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery, and the 12th, under the command of General Omar Nelson Bradley, had galloped across France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Holland at an unexpected pace, overcoming whatever sporadic opposition the retreating German forces could throw in their paths. By September 11, the Americans had reached positions on the German frontier that pre-invasion planners had not expected to reach before May 1945. The door to the heart of Germany seemed to be wide open and beckoning. Once Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) commander General Dwight David Eisenhower realized it, he ordered that the conquest of the Ruhr, Germany’s all-important industrialized area, be made “the main effort of the present phase of operations.” The route to the Ruhr led directly through what is known as the “Aachen Gap,” a relatively flat stretch of terrain with few natural obstacles—terrain that would afford the advancing units excellent maneuverability and fields of fire. Only the ancient city of Aachen, near the junction of Germany, Holland, and Belgium, created a concern for the advancing armies. The scene for the famed Battle of Aachen was set.

The chief concern was with the city of Aachen itself, along with its many suburbs. Attacking armies traditionally hate urban warfare; the advantages are all to the defenders, with almost none for the attackers. Buildings provide unlimited opportunities for cover and concealment, requiring the attackers to treat each building as a bunker that must be knocked out before they proceed to the next one. Streets become natural channels that a handful of defenders can turn into killing zones. Armored vehicles are virtually blind and thus vulnerable to close-quarter attacks. Fields of fire are restricted, as is the ability to maneuver, and the team on offense is usually reduced to attacking with small, decentralized units. Plus, civilians are inevitably caught in the cross fire.

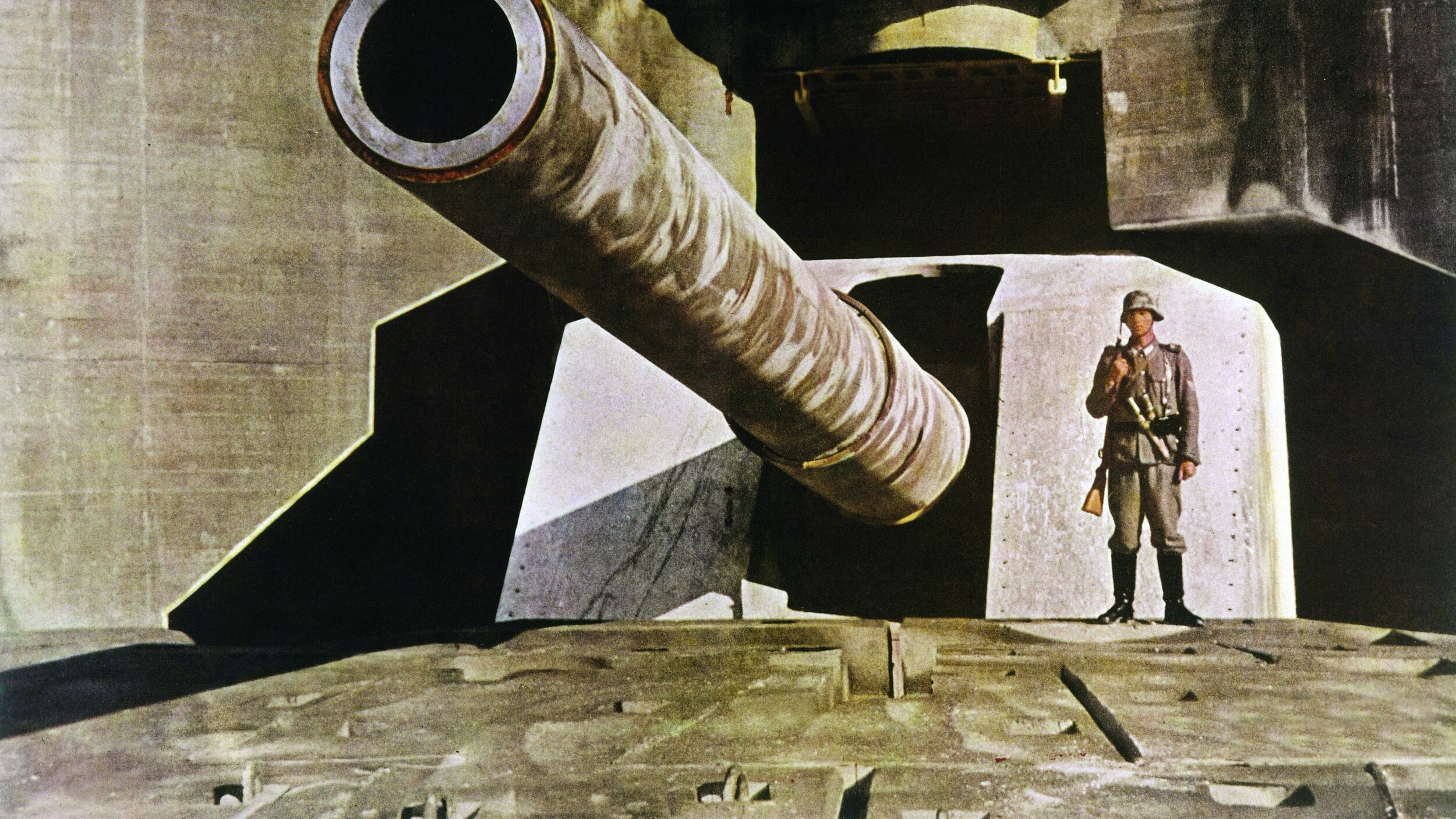

The city was not the only obstacle. Aachen lay within bands of fortifications that looked to be even more formidable than those encountered along the coast of Normandy. The fortifications were known to the Germans as the West Wall and to the Allies as the Siegfried Line.

To describe Bradley’s 12th Army Group as a “juggernaut” would be understating the case. By August 1944, the 12th Army Group was the largest body of American soldiers ever to serve under one field commander. It consisted of four field armies, over 39 infantry and airborne divisions, and 15 armored divisions.

One of the four field armies was the U.S. First Army, under Lt. Gen. Courtney Hicks Hodges. The white-haired, 57-year-old Hodges had, as a youth, attended a year at West Point, dropped out, enlisted in the Army in 1906 as a private, and worked his way up through the ranks. At the time of World War I, he was a lieutenant colonel serving with the 5th Division. During a November 1918 battle along the Meuse River, he earned the Distinguished Service Cross for heroism and leadership under fire. After the war, he served in a variety of staff positions and, during World War II, took the Third Army overseas, where he turned it over to General George S. Patton, Jr. After serving as Bradley’s deputy, Hodges was named commander of First Army when it was formed following the D-Day landings. Not a flamboyant character in the Patton mold, Hodges was a solid, steady, dependable officer.

Under his aegis were three army corps, designated V, VII, and XIX. Two of the corps, VII and XIX, would spearhead the attack against Aachen. Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett, commander of XIX Corps, and Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins of VII Corps were anxious for the operation to proceed, for the longer they waited the worse they feared the weather would become.

Planning for the Battle of Aachen: “No Way Would the Germans Give up This City Without a Fight to the Last German Standing”

None of the commanders of the American units charged with taking Aachen thought the job would be cheap or easy.

Nor did the average soldier. Sergeant Harley Reynolds of Company B, 16th Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, who had already survived Normandy and the push across France and Belgium, said, “I can remember the talk and comments about the city of Aachen, that no way would the Germans give up this city without a fight to the last German standing. It was very unnerving and mystifying that they let us get as close to the city as we did. We were aware of the importance of this ancient city to the Germans and would have given good odds that they would never give it up. We talked about this among the ranks. I felt that there was a good chance that they would possibly drive us back with a big counterattack. We were a finger sticking out in front of the U.S. line—a very dangerous position.”

Adolf Hitler always placed great significance in symbols, and the German city of Aachen was heavy with symbolism for the Führer. As the birthplace of the great Frankish king Charlemagne in ad 742, Aachen evoked memories of the glories of the Holy Roman Empire and the “First Reich.” Not surprisingly, then, Hitler told his generals that Aachen “must be held at all costs …”

As did the Allies, Hitler knew that the Aachen Gap represented the easiest way into the heart of the Fatherland; even before the war Hitler was determined to make it as hard as possible.

Although France had built a series of defensive forts known as the Maginot Line facing Germany, because the articles of peace signed at Versailles in 1919 disallowed German military installations within the “demilitarized” Rhineland region, Germany was not allowed to construct a similar set of defensive positions to protect itself from attack from the West.

Hitler did not take this restriction lying down. In 1934, he ordered the construction of a string of forts east of the exclusion zone in order to gauge French reaction. When there was no reaction, in March 1936 he ordered his troops to violate the Versailles Treaty by reoccupying the Rhineland. Although France and Britain complained to the League of Nations, nothing was done, and Hitler had his first victory. Emboldened, Hitler next began fortifying Germany’s western frontier—from Luxembourg to Switzerland—to guard against possible invasion.

In early 1938, Hitler ordered the line of bunkers, pillboxes, roadblocks, minefields, barbed-wire entanglements, and antitank obstacles and ditches extended northward along Germany’s border with Belgium and Holland. Special attention was paid to protecting Aachen and Saarbrücken. The Führer wanted everything completed by October 1938, as he was planning to invade Czechoslovakia, and he assumed France would declare war on Germany if he did so. It was an impossible deadline, but Organization Todt, Nazi Germany’s state construction arm, did everything possible to meet it.

Under the direction of its founder, Dr. Fritz Todt, Organization Todt was a highly efficient, semimilitary group that created some of the Third Reich’s most impressive public works projects. Beginning with the autobahn system in 1933, O.T., as it was abbreviated, compiled an outstanding record of completing even the most complex and massive projects on time and within budget.

Wehrmacht Engineers Get to Work

After being given the contract for the West Wall on May 28, 1938, O.T. began drawing up plans. In July, construction began with 35,000 civilians starting work; by October some 342,000 men were employed, supported by 50,000 engineers from the Wehrmacht and nearly 200,000 additional men from the Reich Labor Service and Fortification Engineer Staff. All along the construction zones, 100 trains a day brought thousands of tons of concrete, rebar, tools, heavy equipment, and wooden panels for concrete molds.

The West Wall project, however, was too big for even O.T. to complete on time. Although not completely finished, it was not needed—at least not immediately. France and Great Britain complained about Germany’s bloodless takeover of the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia in September 1938 but took no military action. And even after the declaration of war that followed Germany’s subsequent invasion of Poland in September 1939, hostilities in the West did not begin in earnest until May 1940. By then the fortifications were as finished as they would ever be. Only a small number at the time, however, were either armed or manned.

During the four months from June 6 through September 1944, the Germans were reeling and retreating. They had lost at least 400,000 troops in the west, half of whom had been taken prisoner. Losses on the Eastern Front were equally bad or even worse. Every effort by Hitler to stem the tide of eventual defeat had failed.

Was Construction of the West Wall Merely a Sham?

The city of Aachen and its environs were protected by two lines of West Wall fortifications —one to the west, the Scharnhorst Line, and another, even thicker one, behind it to the east known as the Würselen Line. Not only at Aachen but along the entire border dividing Germany from Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and France were vast fields of short, concrete pyramidal tank obstacles known as dragon’s teeth, which were, in turn, covered by minefields, artillery, and the interlocking fires of hundreds of reinforced concrete pillboxes connected by fighting trenches.

Some historians say that the construction of the West Wall was merely a sham to make Germany’s enemies think twice about attacking from the west. Even Winston Churchill saw the West Wall as being an economy-of-force ploy to free up large numbers of soldiers that could be used in more offensive operations.

That situation would change in the fall of 1944.

In September, the U.S. and British armies still had as their objectives the taking of Berlin; the political decision to allow the Soviets to fight for it had not yet been made. Therefore, the Allied forces continued to advance on a broad front to seize the Ruhr, the major industrial area along the Rhine, and then toward the German capital.

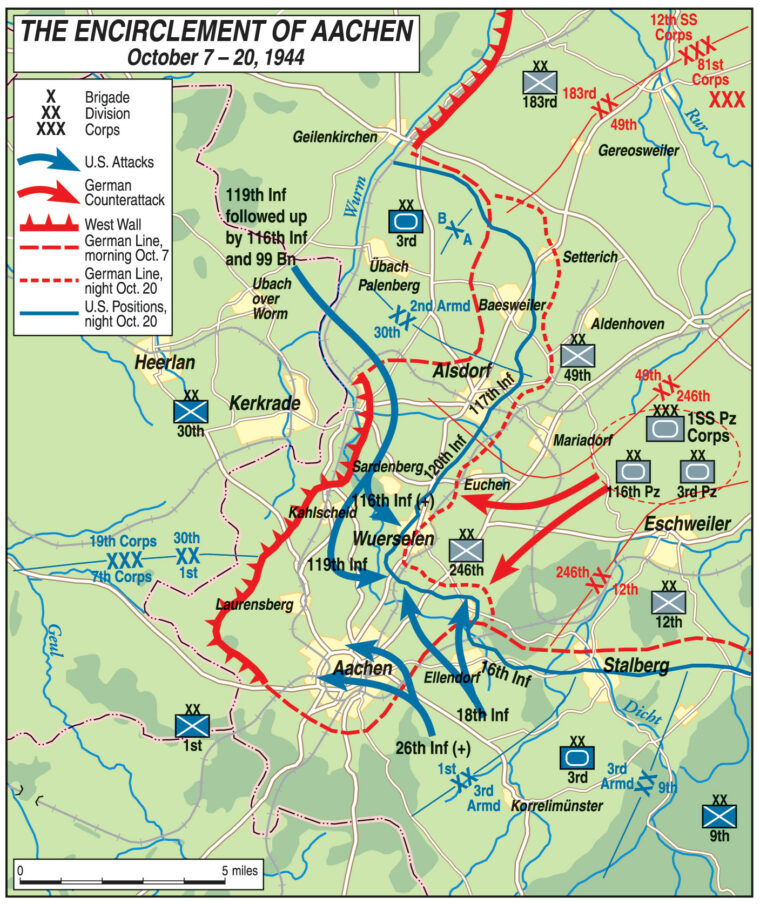

The timing of the operation to take Aachen hinged on how quickly Corlett’s XIX Corps— basically the 29th and 30th Infantry Divisions and the 2nd Armored Division to the north of the city—could break through the defenses around Rimburg, on the Holland side of the border, then cross into Germany and drive south into the gap between Herzogenrath and Alsdorf, then through the towns of Bardenberg and Würselen.

While this phase of the operation was taking place, on September 10, the 1st Infantry Division, as the advance element of Collins’s VII Corps, reached the western outskirts of Aachen and began conducting a series of reconnaissance patrols to determine the strength of the city’s defenses. The VII Corps then planned to drive to the east below Aachen to the vicinity of Eilendorf and Stolberg and hold in place.

Then, once XIX Corps, operating to the north of Aachen, reached Würselen, Hodges would give the order for VII Corps to sweep northward, seize Verlautenheide, a strongpoint in the West Wall, and link up with Corlett’s corps near Würselen. Aachen would then be surrounded, isolated, and ripe for reduction while the rest of First Army proceeded eastward.

The Failure of Operation Market-Garden

Before this plan could be put into effect, however, on September 17 the Allies launched what turned out to be a large but ill-conceived airborne assault in Holland—Operation Market-Garden. Not only did the operation fail to take its objectives, but it also caused thousands of unnecessary casualties and the loss of momentum while it used up considerable supplies that might have been better employed against the Germans at Aachen. The delay gave the defenders time to beef up their defenses.

While some American units were preparing for the Battle of Aachen, others were beginning another operation just to the south—the battle of the Hürtgen Forest. On September 19, what Ernest Hemingway would call “Passchendaele with tree bursts” got under way with the 9th Infantry Division (soon to be followed by the 4th, 8th, 28th, and 1st Infantry Divisions, plus the 2nd Ranger Battalion and a combat command of the 5th Armored Division) advancing into what another author would call “a dark and bloody ground”; the battle for the Hürtgen Forest, which lasted until February 10, 1945, involved more than 200,000 combatants and was one of the toughest battles of the war. But it was Aachen that now captured the attention of Eisenhower, Bradley, and all the rest.

The responsibility for defending Aachen, located 40 miles southwest of Cologne, fell to Maj. Gen. Gerhard Graf von Schwerin, commander of the 116th Panzer Division, a unit that had been badly mauled by the 30th Infantry Division during the summer’s fighting at Mortain. The 116th was still far below strength, possessing only 1,600 men, three tanks, a few assault guns, and two Luftwaffe fortress battalions. A mishmash of other units was also holding Aachen, which brought von Schwerin’s total force to about 12,000 troops.

The city had a prewar population of 165,000, but prior to Hitler’s order for civilians to evacuate Aachen it had shrunk to just 20,000. When von Schwerin arrived, he found about 7,000 panic-stricken civilians still there, afraid to leave. Because there was no way to transport the civilians out of town, the general told them to stay put and then wrote a letter to the Americans offering to surrender Aachen to them.

Unfortunately, the letter fell into German hands before it could be delivered. When Hitler learned of von Schwerin’s act, he had him arrested by the Gestapo. Taking his place was Colonel Gerhard Wilck, commander of the 246th Volksgrenadier Division.

Hitler, meanwhile, was rapidly transferring as many units as he could spare from the Eastern Front to buttress the Aachen Gap, and Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt was recalled from retirement to stiffen the crumbling defenses in the West.

The boundary line between the two American corps ran just north of Aachen, with XIX Corps to the north and VII Corps to the south. “Lightning Joe” Collins did not like waiting, especially now that the whole of Germany seemed open to him. The original plan for his VII Corps called for the 1st Infantry Division to seize Aachen while the 3rd Armored and the 9th Infantry Divisions, south of the city, drove toward Düren in the Roer valley, then on to Cologne on the Rhine. With stocks of artillery shells still precariously low, Hodges finally gave Collins permission to allow the 1st Division to conduct a reconnaissance in force and probe Aachen’s defenses.

Surprisingly, as they approached the thick lines of bunkers and obstacles to the west and south of Aachen, the probing forces initially faced little resistance. Although the antitank barriers presented some difficulties for armor, many of the guns in the fortifications had been removed years earlier to guard the coast of France, and the troops manning the defensive positions were too thinly spread to offer much resistance. Lieutenant Karl Wolf, executive officer of Company K, 16th Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, remembered, “Some of the pillboxes were not even manned.”

The Big Red One and 3rd Armored Punch Through

On September 12, the Big Red One penetrated the lightly held defenses on Aachen’s south side while the 3rd Armored Division encountered only sporadic opposition as it began driving all the way to Stolberg.

Harley Reynolds recalled that his unit was the spearhead entering Germany. “Our company was in the lead as we crossed the border. My section set up machine guns to cover the rest of Company B as they crossed the ‘dragon’s teeth.’ Company B went on into Germany and into a park, where we spent the night. While going into Stolberg, a few miles east of Aachen, we were fired on from our flanks. I guess this wasn’t so strange because this was the kind of fighting we had done all across France and Belgium. To me it was a big chance, but we got away with it. The Germans’ luck finally ran out.”

At other points, fighting was sporadic but fierce. Lieutenant Harold Monica, Company D, 18th Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, recalled that when his platoon encountered machine-gun fire from a pillbox a sergeant in his unit dropped a quarter-pound block of TNT down the ventilation shaft of the pillbox to flush out the occupants. The steel door opened and out came nine very badly shaken German soldiers. “All were covered with dust, rubbing their eyes and ears, and stumbling up the stairs. Sergeant Aiello and I were pleased,” Monica said.

Not all Germans would give up that easily. On September 17, the 1st Division’s 16th Infantry Regiment, which had pushed to the town of Eilendorf, southeast of Aachen, was hit by the most intense artillery barrage it had received since the beaches of Normandy, followed closely by determined assaults by two battalions of well-disciplined infantry of the 27th Fusilier Regiment of the 12th Infantry Division. That same day, the 12th Division’s other two regiments, the 89th Grenadier and 48th Grenadier, attacked the forward positions of the 3rd Armored Division and the 9th Infantry Division. Any thought that taking Aachen would be a cakewalk was quickly dispelled.

None of the attacks succeeded in dislodging any of the American units, but the ferocity of the attacks told the Yanks one thing: now that the war was on German soil, the Germans would defend their homeland with everything they had. There were other worries. The 3rd Armored Division, authorized to have 232 medium tanks, reported on September 18 that only 75 were fit for combat. There were additional supply problems and, to add the final straw, the fine fall weather deteriorated.

Then, just when it seemed that the 12th Army Group, poised on the threshold of Germany, was about to plunge en masse into the country via the Aachen Gap, the growing shortage of artillery shells and fuel reached crisis proportions, forcing General Bradley on September 22 to shut down offensive operations.

General Collins later said that his corps “ran out of gas, we ran out of ammunition, and we ran out of weather. The loss of our close tactical air support [because of cloud cover] was a real blow.”

The Germans took advantage of the American army’s inertia. On September 24, Staff Sergeant Joseph E. Schaefer of Company I, 18th Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, was part of a platoon defending a crossroads south of Aachen when it was attacked by a superior enemy force. One of the company’s squads was taken prisoner, another abandoned its position, and only Schaefer’s squad remained.

German fire became so intense that Schaefer ordered his men to take up positions in a nearby house. Despite continued attacks, Schaefer’s men repulsed every one; the sergeant personally accounted for between 15 and 20 German dead. He then went out looking for the enemy, captured 10 of them, and even freed the squad that had earlier been taken prisoner. For his courageous deeds, he was awarded the first of seven Medals of Honor that would be earned by American soldiers during the siege of Aachen. Most importantly, he and his squad prevented the enemy from taking the crossroads.

At last sufficient supplies of ammo and fuel began to reach American forces at the front, and the drive to capture Aachen and push eastward was ordered to resume. General Hodges went ahead with his decision to assault the city with a pincer movement. Maj. Gen. Leland S. Hobbs’s 30th Infantry Division, supported by the 2nd Armored Division under Maj. Gen. Ernest Harmon, would strike from the north. South of Aachen, VII Corps would drive to the east with the 1st and 9th Infantry Divisions and 3rd Armored Division, reach Stolberg, and then turn sharply north, linking up with XIX Corps at Würselen. To get into Germany, XIX Corps would need to attack eastward out of Holland, cross the Wurm River, which is more of a stream than a major river, and break through the outer line of West Wall fortifications north of Aachen.

Since XIX Corps had the farthest to go, it would begin its phase of the operation on October 1, 1944; four days of artillery bombardment would precede the assault. Six days later, Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division, already inside Germany, would then strike Aachen from the south. It was planned that the 18th Infantry Regiment from the Big Red One would then circle to the east of the city, head north, and link up with the 30th Division to prevent Wilck’s garrison from either escaping or being reinforced. It was a solid plan but, like many military plans throughout the ages, it would go awry once the first shot was fired.

On September 26, a mighty roar shattered the autumn air as 26 battalions of American artillery from XIX Corps, the 30th and 29th Infantry (operating on the 30th’s left flank), and the 2nd Armored Divisions opened up to knock out the hundreds of pillboxes in XIX Corps’s 11-mile sector between Geilenkirchen and Aachen. The artillery kept it up for four days, evoking memories of the massive barrages of the First World War and nearly exhausting the precious stocks of ammunition.

An intense aerial bombardment was also scheduled to take place prior to H-hour but was scaled back at the last minute because of heavy overcast—much to the relief of the old-timers in the 30th; they still recalled the heavy casualties suffered during the Operation Cobra breakout in Normandy when American aircraft accidentally bombed 30th Division positions.

Because of heavy downpours, the American infantry and armor attack on Aachen’s northern suburbs was delayed for 24 hours. On the gray, dismal morning of October 2, following another artillery preparation, the infantrymen of the 117th Infantry Regiment, the spearhead of Hobbs’s “Old Hickory” division, left its line of departure west of Geilenkirchen and began advancing into the torn-up, still smoldering landscape, heading south for Palenberg and Übach.

Heavy Fighting Near the River

The artillery and mortar fire provided a rolling barrage for the foot soldiers as they trudged forward carrying duckboards, makeshift bridges, to throw across the Wurm River, which divides part of Germany from Holland between Rimburg and Herzogenrath. German return fire against the GIs was intense, however, and Yank squads and platoons were cut to pieces as they approached the river. In less than an hour, one company of the 1st Battalion, 117th Infantry, lost 87 men, seven of them killed.

The GIs soon discovered to their dismay that the thousands of artillery shells that had been expended against the German pillboxes had barely scratched a defender; each pillbox and fighting position had to be knocked out one at a time with grenades, pole charges, bazookas, and flamethrowers. By the end of the day, the 30th Division had made small but significant penetrations into the German defensive line.

With the 29th Division conducting a diversionary attack northwest of Geilenkirchen, the 30th Division managed to breach the West Wall fortifications in the area between Rimburg and Übach-Palenberg. This assault was aided by American aircraft of the IX Bombardment Division, but the bombing was ineffective. Tragically, one group of medium bombers, owing to poor navigation and inadequate target identification, even flew off course and accidentally bombed a Belgian town 28 miles west of Aachen, killing 34 civilians.

Meanwhile, the ground battle wore on. While crossing an open field devoid of cover, the soldiers of Company B, 117th Infantry, 30th Division, were forced to shelter behind the torn carcasses of cows that had been killed by the barrages. When Company B finally reached the enemy pillboxes, they put them out of action with flamethrowers.

During the especially tough battle for Palenberg, a hand grenade duel between opposing forces took place. Private Harold G. Kiner, a 20-year-old rifleman with Company F, 117th Regiment, was trying to dislodge enemy troops from their position when a German potato-masher grenade landed between him and two other soldiers. Without hesitation, he threw himself on the grenade, smothering the blast and saving his comrades at the cost of his own life. Kiner’s heroism would be recognized with the Medal of Honor.

As the 30th’s right flank, the 119th Regiment crossed the Wurm near Rimburg on the Dutch side, where an old castle occupied by German troops stood. Surrounding the castle was a moat covered by thick woods. A bridgehead over the Wurm between Rimburg and the castle became the scene of intense fighting. The Germans tried to mount a series of counter- attacks during the night to stop the inrush of American troops and tanks, but their efforts were thrown back with heavy losses. The enemy was not about to abandon the area without putting up a fight, however, and fought back with artillery.

American tanks had no easier going than the infantry. The heavy rains had turned the banks of the Wurm into deep bogs. One tank after another got stuck in the soft, wet earth and could not move. Engineers brought up bridging material and began constructing a treadway bridge under enemy fire. By the end of the day, the tanks had started to cross the stream but were too late to help the riflemen, who were trying to defeat each pillbox without the help of the Shermans’ 75mm guns.

And so it went all day, with small, determined bands of attackers taking out pillboxes one by one. The only problem was that there were several hundred of these concrete fortifications all the way to Aachen and beyond. At the end of the first day of fighting, the leading battalion of the 117th Infantry had lost 146 men, including 12 killed; another battalion had 58 wounded and 12 dead. Aachen was still 10 miles away.

On October 3, the 117th’s commander decided to throw his reserve battalion, the 3rd, into the drive to take Übach, with an eye on cutting the Geilenkirchen-Aachen highway and occupying the high ground east of the Übach-Beggendorf road. But the Germans were dug in strongly at Übach and put up a stubborn resistance. The foot troops needed tanks to take Übach, so General Corlett ordered the tanks and halftracks of the 2nd Armored Division’s Combat Command B to get there on the double. The bridgehead over the Wurm was still not secured, however, and the American commanders risked having a disaster on their hands.

Luck was with the tankers, and soon they were traveling south toward Übach. Heavy German shelling kept the tanks pinned down outside the town, while infantrymen who had penetrated into Übach took cover from the flying metal in shattered buildings. Advancing further was out of the question. The German corps commander, meanwhile, was rushing reinforcements into the area, seeking to destroy the column of American armor that was strung out from the bridgehead several miles back. Well before dawn on October 4, the German counterattack, as disorganized as it was, struck the American tanks and half-tracks. Only a timely artillery barrage prevented the destruction of the armored relief force.

A few hours later, the Germans attacked again, this time hitting the 119th Infantry Regiment. One battalion of the German 49th Division, supported by two assault-gun brigades, caused great consternation in the American ranks, even forcing one company to retreat in fear and confusion. Short rounds from their own artillery, however, broke up the German attack. By the time they were ready to attack again, the 119th had regained its composure and was waiting. At Übach, the Germans organized another attack to dislodge the Americans from the town but were halted by Task Force 1 of 2nd Armored’s Combat Command B—but not without considerable bloodshed.

Now it was time for the American armored troops of Task Force 2 to resume the offensive. By late afternoon on October 4, it took the high ground near Hoverhof. The unit’s twin, Task Force 1, engaged seven self-propelled guns and knocked them all out with a loss of just two of its own tanks. Two days later, the American advance was halted once more after the Germans brought up infantry and heavy guns to block the way. The battle north of Aachen was in danger of becoming a stalemate.

Clarence Huebner’s 1st Division had found the going south and southeast of Aachen to be slightly easier, but only slightly. Lieutenant Karl Wolf’s Company K, 16th Infantry, came under massed artillery fire directed from German observation posts on Crucifix Hill (so named because of a large cross on its summit) and Verlautenheide Ridge. “Just before midnight on October 3,” he recalled, “the Germans launched the heaviest artillery barrage I was in during the war. Fortunately, we were in an abandoned German pillbox and no direct hits occurred.” It was estimated that some 3,000 to 4,000 rounds landed on Company K’s position that night.

The decision was made. The German observation posts on Crucifix Hill and Verlautenheide Ridge, and a third hill, called the Ravelsberg, would need to be taken out. Holding these features were the 246th Division plus an understrength battalion of the 275th Division, a battalion of Luftwaffe ground troops, a machine-gun fortress battalion, and a Landesschützen battalion. The 18th Infantry Regiment was given the daunting assignment.

Fires Tear Open the Predawn Sky on October 8

An hour-long saturation bombardment by 11 battalions of artillery and a company of 4.2-inch chemical mortars lit up the predawn darkness of October 8. The dazed defenders at Verlautenheide put up little resistance to the 18th Infantry’s 1st Battalion. It was a different story at Crucifix Hill.

Spearheading the assault against Crucifix Hill was Company C, 18th Infantry, under the command of Captain Bobbie Brown, a man one of the other officers said “clearly loved war.” On October 8, Brown led his men up the hill under a rain of bullets and shells. Brown personally thrust a satchel charge into the firing aperture of a particularly troublesome pillbox and knocked it out. He then crawled to another fortification and destroyed it, too. Another pillbox had his men pinned down, and he crawled through intense fire to silence it. Although wounded three times during his one-man attack, he refused medical aid and continued to encourage his men in their attacks on the hill’s concrete defensive positions. Soon Crucifix Hill was in American hands. For his courageous actions Brown was awarded the Medal of Honor.

In the darkness of the following night, American infiltrators slipped into German positions atop the nearby Ravelsberg and won the summit without firing a shot. Unaware that the Yanks were in control of the peaks, German supply teams were captured while bringing hot food for their comrades—hot food that was quickly consumed by the grateful Americans.

The German counterattacks began almost as soon as the enemy learned that the Americans were now in control of the three hills. The German 12th Division launched a series of infantry attacks accompanied by artillery that plastered American positions. Despite the shelling, two rifle companies from the 18th Infantry Regiment managed to crawl from their foxholes, organize an attack, and seize the town of Haaren, on the Aachen-Jülich highway, one of the Germans’ major supply and reinforcement lifelines. On October 10, the advance elements of two more German divisions arrived and began hammering away at the 18th Infantry, trying without success to dislodge the troops from their positions.

That same day, in an effort to try diplomacy before resorting to more force, an ultimatum from General Huebner was delivered to Colonel Wilck in Aachen, demanding that he surrender the city before American guns reduced it to rubble and more people were killed. The demand was rejected. A two-day bombardment of the city then commenced.

On October 9, the 1st Battalion, 120th Regiment, 30th Infantry Division, was ordered to take part in an afternoon attack on the fortified village of Birk, three miles north of Aachen. Captain Murray S. Pulver, commander of Company B, 120th Infantry Regiment, was in his usual place—the thick of the fighting. His unit, along with Company A and six tanks, attacked abreast across 400 yards of open ground. The attacking force had hardly gone halfway when the field was raked by artillery, rifle, and machine-gun fire. The six tanks were knocked out within minutes of leaving the line of departure.

Ordered to pull back, A and B Companies were then directed to resume the attack at dusk by hitting Birk on the flank through the village of Bardenberg. Pulver said, “It was almost dark by the time we launched our attack. We immediately ran smack into a counterattack by the enemy, directed at Bardenburgh. After a savage firefight with German tanks and infantry, we were ordered to back off and resume our former positions. We were saved from extinction by the darkness. It had been a poorly planned and executed attack, and many brave soldiers never returned to their former positions.” Because of the failure, the battalion commander was relieved of his command.

Casualties were heavy. Russell Albrecht, another soldier in the 120th Infantry, recalled that while his unit was under fire, “My captain walked by me, patted me on the shoulder, and said, ‘How are you doing?’ He got about 10 feet from me and got a bullet in his head.”

From midnight until 4:30 am, Birk was relentlessly pounded by artillery. Although nearly worn out from their earlier ordeal, A and B Companies were again ordered into the attack, this time through a thick, early morning fog.

Captain Pulver said, “We moved fast and were on top of the exhausted enemy before they could fire a shot. About 50 prisoners were taken; the rest of the defenders escaped to the south.”

The result of the battle was that Company B gained control of Birk and held a hill overlooking the road network leading out of Aachen to the east. But the position was tenuous at best, and soon the company was subjected to attacks by every German unit coming to break the siege of Aachen.

Pulver’s men repulsed many counterattacks for several days but they held their ground and refused to yield. In recognition of their bravery, the 1st Battalion later received a Presidential Unit Citation.

In other parts of the 30th Division’s sector north of Aachen, the unrelenting combat went on. Hobbs’s men were still struggling to drive south of Bardenberg and punch through Würselen to reach the 1st Division; the Old Hickory team had already suffered 2,000 killed and wounded since the operation began 10 days earlier. On October 12, a battalion of tanks from the 2nd Armored Division and the 116th Regiment of the 29th Infantry Division were attached to the 30th. With this added strength, Hobbs’s men would finally be able to effect the link-up with the 1st Division, an event that was still several days into the future.

In Bardenberg on October 12, the fourth Medal of Honor of the battle was earned posthumously by Staff Sergeant Jack Pendleton. A member of Company I, 120th Infantry, 30th Division, Pendleton and his men had advanced approximately two-thirds of the way through Bardenberg when they came under fire from a nest of enemy machine guns. Pendleton’s Medal of Honor citation reads: “This enemy strong point was protected by a lone machine gun strategically placed at an intersection and firing down a street which offered little or no cover or concealment for the advancing troops. The elimination of this protecting machine gun was imperative in order that the stronger position it protected could be neutralized.

“After repeated and unsuccessful attempts had been made to knock out this position, S/Sgt. Pendleton volunteered to lead his squad in an attempt to neutralize this strongpoint. S/Sgt. Pendleton started his squad slowly forward, crawling about 10 yards in front of his men in the advance toward the enemy gun. After advancing approximately 130 yards under the withering fire, S/Sgt. Pendleton was seriously wounded in the leg by a burst from the gun he was assaulting. Disregarding his grievous wound, he ordered his men to remain where they were, and with a supply of hand grenades, he slowly and painfully worked his way forward alone. With no hope of surviving the veritable hail of machine-gun fire which he deliberately drew onto himself, he succeeded in advancing to within 10 yards of the enemy position when he was instantly killed by a burst from the enemy gun.

“By deliberately diverting the attention of the enemy machine gunners upon himself, a second squad was able to advance, undetected, and with the help of S/Sgt. Pendleton’s squad, neutralized the lone machine gun, while another platoon of his company advanced up the intersecting street and knocked out the machine-gun nest which the first gun had been covering. S/Sgt. Pendleton’s sacrifice enabled the entire company to continue the advance and complete their mission at a critical phase of the action.”

It was that kind of heroism that would be necessary at the Battle of Aachen to take the city and its suburbs.

On October 12, American artillery lobbed 5,000 rounds against German positions while the P-38 Lightning and P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers of the IX Tactical Air Force pounded the enemy with 99 tons of bombs. However, as the GIs on the ground soon discovered, all this softening up did was create more rubble and debris. The defenders were barely touched.

With German soldiers fighting on German soil, German opposition continued to be stiff and studded with fierce counterattacks. Harmon’s 2nd Armored Division was brought up and assisted in the reduction of the defenses and the disruption of the counterattacks. After four days of nonstop fighting, the 30th had captured or destroyed 200 bunkers and pillboxes, but the possibility of overcoming the ever-increasing opposition any time soon seemed remote at best.

Since it appeared that the link-up between the 1st and 30th Divisions would not happen quickly, General Huebner ordered the Big Red One’s 26th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel John F.R. Seitz, to penetrate into the heart of the city.

The plan was to have the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 26th, reinforced with tanks, tank destroyers, artillery units, flamethrowers, bazookas, and additional machine guns, circle around to the east and southeast of Aachen and enter from that direction. In the event that any serious resistance was encountered, a self-propelled 155mm howitzer was added to the mix.

The 1st Division launched a series of attacks along Aachen’s southern perimeter. The Germans answered with mortars, machine guns, and 88mm artillery fire. The going was, in a word, tough. In the meantime, the 16th Infantry was directed to drive due east along Aachen’s southern boundary, take the village of Münsterbusch, and then advance toward Stolberg.

Lieutenant Karl Wolf recalled that the 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry, took heavy casualties during the drive. “The battalion had lost 300 men in five days at that point,” he said. “In Stolberg, which had pretty well been destroyed, the fighting was house to house.”

Sergeant Harley Reynolds felt that there was one reason why Stolberg was an important objective—and why the Germans defended it so intensely. “It was high ground,” he said, “but, better yet, it was the location of main valves for the water line to Aachen. We repulsed counterattack after counterattack by the Germans for this prize. The ammo shortage really hit us. If the Germans could have sustained their counterattacks, they could have run us out of ammo. This was one of the few times the Germans used their air force to try and dislodge us. They were able to dive-bomb us every night for the whole time we were there. But we took the main valves and cut off the water supply and held this objective until Aachen surrendered.”

On the morning of October 13, the 26th Infantry began its assault into the city proper, clambering over a high railroad embankment to enter Aachen from the southeast. Confronted by a maze of streets filled with toppled masonry, the GIs adopted a strategy they called “Knock ‘em all down.” If a building stood in their path, the Americans used their heavy firepower to knock down any standing structures, chase enemy soldiers into basements, and finish them off with grenades, flamethrowers, and automatic weapons.

The 155mm howitzer was especially effective. When the infantry discovered that trying to advance down the streets was too unhealthy, the big gun was brought up, aimed at a block of buildings, and then fired. The projectiles tore perfect holes through multiple walls, allowing the foot soldiers to advance from one building to the next without ever stepping outside and exposing themselves to the bullets flying down the streets.

From his vantage point on a hill in Stolberg, Sergeant Harley Reynolds watched the battle for the city evolve. Aircraft, too, weighed in. “You can’t believe the empty shell casings dropping on us from all our planes doing their strafing and dive-bombing runs on Aachen,” he said.

By Hook or by Crook

The GIs were very creative in their assault on the city. At one point, a combat engineer unit filled an Aachen streetcar with explosives, lit a time fuse, then sent it careening down the tracks into the city. Charles MacDonald, in the Army’s official history of the battle, noted, “Whether it did any actual damage to German installations was irrelevant in view of the impish delight the engineers derived from it.”

Also on October 13, Captain James M. Burt, commanding a tank company in the 2nd Armored Division, earned for himself the Medal of Honor during the battle for Würselen. Although he was wounded early that morning and escaped from two Shermans that had been destroyed by German fire, he forgot about his injuries and personally reconned enemy territory, directed artillery fire from exposed positions, and rescued several wounded men. His citation reads: “Captain Burt held the combined [tank and infantry] forces together, dominating and controlling the critical situation through the sheer force of his heroic example.”

Near the center of Aachen is a public park and hill known as the Lousberg, rising 862 feet; the GIs would rename it Observatory Hill. Near the base of the hill stood a sizable hotel and spa, the Quellenhof. As their perimeter continued to shrink, Wilck and his staff took up residence in the hotel and made it their command post.

The battle for the heart of Aachen turned into a real slugfest. As members of the 26th Infantry moved slowly and cautiously through the city, they were sometimes surprised by German defenders popping up from manholes behind them. A few grenades into the sewers and the piling of debris on top of the manhole covers took care of that problem.

Well-hidden antitank guns continued to take their toll on American Shermans, and every street corner turned into a shooting gallery and the tanks into sitting ducks. On October 14, the 30th Infantry Division pushed off before dawn in an attempt to close the gap between the 30th and the 1st Infantry Division, but again little progress was made against determined opposition. The sticking point seemed to be concentrated around Würselen.

Frank Moody, a platoon sergeant with Company F, 120th Regiment, 30th Infantry Division, was leading his platoon across a beet field near Würselen when an artillery barrage tore into them; he told his men to run and take cover in a sunken railroad cut. On the other side of the tracks was a German King Tiger tank along with two smaller tanks. A machine gun raked the area from a nearby water tower. Moody crawled atop a knocked-out panzer and called for his 30 men to join him. Only 14 responded. Luckily, they managed to get back to the company command post. “The medics went out and brought back 16 naked dead bodies,” he said.

Later, a single shot by a German sniper killed Moody’s scout beside him. Outraged, Moody said, “I got shook up and ran up to this German, took the rifle out of his hands before he could kill any more, and beat him half to death with it. Then my men stopped me. We went on to capture 15 more prisoners.”

Even high-ranking officers were not immune from the flying projectiles. Brig. Gen. William K. Harrison, Jr., the assistant commander of the 30th Division, was wounded sometime during the battle. In a letter to his son, he explained how he was hurt: “Yes, that was a small fragment but you would be surprised what a little piece like that can do. The shell, which is steel, is burst into a lot of pieces by the explosion inside of it. For a short distance the pieces travel very fast. The doctor told me that a little piece like that can break a man’s arm or go through his skull to kill him. Happily, the three that hit me did not strike anything vital.”

Slow but Steady Progress

Day by day, block by block, and building by building, small sections of Aachen were cleared of defenders by the attackers from the 26th Infantry Regiment. The casualty lists mounted on both sides, but still the Germans gave no sign of wanting to surrender.

The German LXXXI Corps commander, General Friedrich Köchling, did his best to send reinforcements to Wilck’s aid. Eight assault guns arrived on the evening of October 14, and an SS battalion showed up the next day. These were thrown into a counterattack in an effort to break the American ring that was forming around the Hotel Quellenhof. The counterattack failed. Wilck and his staff managed to slip out of the hotel, however, and set up a new command post in a huge air raid shelter, leaving behind a well-armed contingent in the Quellenhof ready to fight to the last bullet.

In the meantime, while XIX Corps was still struggling to overcome the opposition north of Aachen, General Hodges’s patience with the 30th Infantry Division’s slow progress was about at an end. Hobbs’s men were supposed to have linked up with the 1st Division on October 8, and it was now a week later—and still no link-up. Continuing to press General Corlett to light a fire under Hobbs, including threatening to relieve Hobbs of command, Hodges simply could not believe that the German defense was as fanatical as it was, especially when compared with VII Corps’s relatively quick and easy passage through the southern fringes of Aachen.

Finally, Hobbs decided to cease banging his head against a stone wall, and he sent one of his regiments, the 119th, across the Wurm into the village of Kohlscheid and then in a flanking maneuver southward along the river’s eastern bank. Meanwhile, elements of the 120th and the attached 116th Regiment from the 29th Division continued to assault Würselen. The 117th and 120th would stage diversionary attacks near Alsdorf.

Before dawn on October 16, the new operation was set into motion. By noon Kohlscheid was in American hands, but fighting farther to the east did not go as well. Pinned down by intense fire from a series of pillboxes, the 2nd Battalion, 119th Infantry, could make no headway until a sergeant named Holycross and a handful of Shermans led a platoon against the emplacements and systematically knocked out seven of them and captured 50 prisoners. Heavy German fire, along with a heavy rain, prevented the tanks from going any farther. It seemed that once again the American drive would bog down and tally nothing but more casualties.

However, the diversionary attack around Alsdorf by the 117th and 120th Regiments and the pressure exerted by the 116th at Würselen began to pay dividends. Shifting their attention from the 2nd Battalion, 119th Infantry to the new threat, the Germans enabled the 2nd Battalion to make progress and take its objective, Hill 194, but not before it lost a number of men in the process.

October 16 saw an intensification of the fighting as the Germans continued to pour reinforcements into the battle. Near the town of Eilendorf, for example, the 1st Division’s 16th Regiment was attacked by elements of the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division but fought off the attack.

Another Medal of Honor was earned that same day at Würselen by Staff Sergeant Freeman V. Horner, Company K, 119th Regiment, 30th Division. Machine-gun fire from houses on the edge of the town pinned the attackers in flat, open terrain 100 yards from their objective. As they lay exposed in the field, enemy artillery observers directed fire upon them, causing heavy casualties.

Realizing that the machine guns had to be eliminated to allow the company to advance out of the killing zone, Horner stood up with his Thompson submachine gun and charged toward the machine-gun nest. Just as he reached a position of seeming safety, he was fired on by another machine gun that had remained silent until that time.

He coolly wheeled in his fully exposed position while bullets whizzed past him, and he killed two German gunners with a single, devastating burst. He turned to face the fire of two other machine guns and, dodging bullets as he ran, rushed the enemy positions 50 yards away. The Germans abandoned their weapons and took cover in the cellar of the house they occupied.

Horner burst into the building, dropped two grenades into the cellar, and yelled for the Germans to surrender. After the blasts, four stunned men came out with their hands up. By his extraordinary courage, Horner destroyed three enemy machine-gun positions, killed or captured seven of the enemy, and cleared the path for his company’s successful assault on Würselen.

With enemy resistance at Würselen finally broken, at 4:15 pm on October 16 a three-man patrol from the 30th Division’s 2nd Battalion, 119th Infantry, was spotted by soldiers of the 1st Division’s 18th Infantry east of Aachen. The patrol, from the 2nd Battalion’s position on Hill 194, braved enemy fire and reached the base of the Ravelsberg, their uniforms wet, muddy, and torn by shrapnel. From above them, atop the hill, came shouts: “We’re from K Company, 1st Division. Come on up.”

Two exhausted men from the 30th Division —Privates Edward Krauss and Evan Whitis— could only shout back: “We’re from F Company. Come on down.”

The men from the two divisions then met and shook hands. The city was now completely encircled and the Aachen Gap was at last closed. But the fighting was not yet over—not by a long shot.

The battles in Aachen’s suburbs remained just as fierce as the fighting inside the city. On October 18, on a hill near the town of Haaren, between Aachen and Verlautenheide, Sergeant Max Thompson was with Company K, 18th Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, when it came under an hour-long enemy artillery barrage.

When the shelling stopped, and while helping to move some of his wounded men to the rear, Thompson saw emerging from the woods a battalion of German troops and a number of tanks heading straight for him. He manned a .30-caliber machine gun in an attempt to slow the attack but a round from one of the tanks destroyed the gun. Thompson then picked up a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), halting the leading elements of the attack and causing those following to disperse. Then the BAR jammed. He tossed it aside and found a bazooka, using it to knock out one of the enemy’s light tanks before the German fire forced him to fall back.

That night, Thompson and his squad were given the mission of retaking the hill, including the pillboxes that were now back in German hands. Under cover of darkness, Thompson, at the head of his squad, crawled forward and fired rifle grenades through the embrasure of a pillbox. The Germans fought back and wounded the sergeant, but he kept up until his one-man assault inspired his men and sent the enemy fleeing. For his courage, Max Thompson was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Also on October 18, it came time for the Americans inside the city, Lt. Col. John T. Corley’s 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry, to assault the Hotel Quellenhof, one of the last points of resistance. Second Lieutenant Wiliam D. Ratchford led his platoon, charging into the lobby of the opulent hotel, then proceeding to clear it out floor by floor, room by room. Finally, Ratchford’s men forced the defenders into the basement, where they were finished off with grenades and automatic weapons fire.

The Siege Could Not be Lifted

By now the American encirclement of Aachen had become impenetrable, and the Germans gave up their efforts to lift the siege. On the afternoon of October 19, Colonel Wilck, from his command post inside the city’s massive, four-story air raid shelter at 348 Rutscherstrasse, issued the following directive to his troops:

“The defenders of Aachen will prepare for their last battle. Constricted to the smallest possible space, we shall fight to the last man, the last shell, the last bullet, in accordance with the Führer’s orders. In the face of contemptible, despicable treason committed by certain individuals, I expect each and every defender of the venerable Imperial City of Aachen to do his duty to the end, in fulfillment of our Oath to the Flag. I expect courage and determination to hold out. Long live the Führer and our beloved Fatherland!”

Learning that Wilck and his command staff were holed up in the shelter, Colonel Corley brought up the 155mm howitzer he had dubbed Big Bertha and directed the gun crew to blast away at the thick walls of the structure. While the shells only chipped large chunks of concrete from the exterior, the tremendous noise reverberated inside. Before long, a white flag appeared at the door of the shelter and out stepped two American GIs—two of 30 Americans the Germans had been holding as prisoners. A cease-fire was declared, and soon Colonel Wilck, apparently disobeying his own order to fight to the last man, emerged and was taken to Corley’s command post.

At five minutes past noon on October 21, 1944, the 1st Division’s assistant commander, Brig. Gen. George A. Taylor, accepted Wilck’s surrender. The first major German city to fall into Allied hands was at last secured.

The High Cost of Aachen

The casualty toll on both sides for the battle of Aachen and its suburbs was heavy. The 30th Division had lost some 3,000 men killed and wounded since its assault on the Siegfried Line began on October 2, but the division had captured 6,000 of the enemy.

According to General Huebner, the 1st Division’s casualties were significantly less—150 killed and 1,200 wounded. In turn, the Big Red One had taken 5,637 prisoners. Figures for Germans, both military and civilian, who died in the fighting are unknown. Approximately 6,000 of the 7,000 civilians who remained in the city had been removed by U.S. Army Military Government units during the fighting and placed in protective custody in the suburb of Brand.

Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall had once expressed his desire to General Eisenhower that the U.S. Army Band should play a concert in the first major German city captured by the Americans.

Ike’s naval aide, Captain Harry Butcher, noted, “[Mars hall] said he wished this could be done [in Aachen], but the concert would have to be on an occasion such as a ceremony to include [First Army commander] General Hodges. [Ike] felt it unwise to permit the band to play within 3,000 yards of the front line. If the Germans heard the music, there would be a refrain of artillery, and not only members of the band, but General Hodges might be killed. Consequently, he disapproved the idea.”

For the Americans, the capture of Aachen was a significant event, kicking in the door that allowed the Allied drive toward the Ruhr and the Rhine to continue. The Battle of Aachen was at last over. The weary, grimy GIs sat in the rubble of the city, ate their C rations, wrote letters home, and counted their losses. The first chill of winter was in the air. Yet, the bloody battle of the nearby Hürtgen Forest was already heating up; the Germans would fight as tenaciously for the Hürtgen as they had for Aachen. Then in December would come the major test—the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s largest counteroffensive in the West.

Much urban fighting in hundreds of small villages and large cities still lay ahead, and the GIs who survived Aachen wondered what would happen if they were selected to assault Berlin. Through the grace of God, they did not have to find out.

My dad was in Aachen, mom had a picture of him taken there with his foot propped on a dud bomb. His name was George Van Deuson but I don’t know what unit he was in, except I remember a 1stArmy patch in the stuff mom had. Dad never said much about the war except he did say he was in a foxhole for three weeks during the Battle of the Bulge. He got out of the army as a sergeant, but I understand he went up and down in rank, even rising to second looie at one point. He did get a Bronze Star.

I never had a real opportunity to talk to him about the war because he died at age 40 from a heart attack. If anyone can offer any help with his unit I would appreciate it greatly.

My dad faught at Aachen, K company 26th Infantry Regiment Big Red One. He didn’t talk much about his time there Did always talk about his squad members and his Lt.C.E. Brink. We have nearly two hundred Letters sent home to mom. Many were checked By L t. C.E. Brink. I would to find out more about him. They are all Hero’s.

To Mr. Eckman above: my dad was in G Company 26th Regt Big Red One. He was a 2nd Lt and arrived France late Feb (after a year in Alaska & officers school). He arrived in Aachen by first week of March 1945. It was being shelled by Germans, trying to take it back. So they had to leave the next morning. He went on to Cologne to join his unit. Cologne had just been taken. He was with the 26th crossing the Roer River and went north into the Harz Mountains. He fought here and was captured near Torfhaus, but 3 days later another company arrived (wonder if it was your dad’s ??) but had to walk 70 miles to Co G location. The 26th and Big Red One were reassigned to Patton’s 3rd Army in Czechoslovakia, taking the border towns of Cheb and Luby, where they stayed as war ended. He was sent back with Big Red One just outside Nuremberg, where they rebuilt the Stalag 13 camp for SS prisoners who were being processed for the Trials. Would be very interested if you dad’s letters describe these events and locations.

Mr. Hart so glad for your reply. I don’t know if our dads crossed paths. My dad went in the Army May of 1944. He was sent to the Ardennes ,early October and was discharged November, 1945. His company also went to Czechoslovakia, then was sent to Nuremberg. One of his letters home mentions guarding General Goring. I don’t know if he did , however, it’s mentioned in the letter home. Dad was wounded March 19,1945, a sniper shot, luckily he didn’t require hospitalization. Have you researched after action reports of Company G and the attached units? I’m sure you will see the activities of his company. I’m sure you are very proud of your dad. The are all heroes. Thanks so much

Mr Hart, my grandfather was a ssgt for second platoon G Company 2nd Battalion 26th Infantry. He landed on D-day and was finally discharged in Nov ’45. Wounded twice within a week in November ’44 in the Hurtgen forest. Wounded in April ’45 and sent home. He received a bronze star and a Silver star. I have copies of the company morning reports from June through April. Most are readable but October’s is very blurry and impossible to read. I would love to talk to you and compare notes.

Mr. Hart, so glad for your reply.I don’t know if our dads crossed paths. My father went in the Army May of 44, was sent to the Ardennes, I think early October. His Company also went to Czechoslovakia, then to Nuremberg. One letter home mentions General Goring being there. I don’t know if dad guarded him or not. It’s possible our dads were at the same place. I thought my father was at the place where the trials were held. May have been where your dad was too. He was discharged November, 1945. I’ve been researching company K and attached units “ after action reports” This gives a good a good idea of where they were, and what they were going through. Maybe you could see about company G and your Dad. I find it interesting . Your Dads story is very interesting and I’m sure your very proud of him.

Does any one know anything about Carl W. Trievel, my father.

He fought in Africa, France and the in the Philippines in Korea.

I recently found out that a distant relative was one of the casualties on Crucifix Hill. Private Edwin Wilkerson, 1st Battalion and apparently Company C, 18th infantry regiment was mortally wounded in the thigh during the assault. He was struck by shrapnel when the Germans shelled the soldiers attempting to take the hill.

Private Wilkerson was taken to an aide station where he died from his wounds. He was 27 years old, 5’6” blonde and blue eyed. He had survived the Normandy landing, the fight across France and Belgium and wounding somewhere above the beaches . He rests in peace in Belgium.

Interesting story . If you haven’t done so yet, you could look for “ after action reports” of your relatives unit .It details daily activities of the Company during the war. Also supporting units such as tank destroyer battalions offer lots of detail. Good luck.

PFC John Dennis Aderhold of Douglasvile, GA was with the 1st Infantry Division, 16th Regiment. He was somewhere in the Aachen, Germany area when he was killed in action. He earned a Bronze Star medal in Sicily. If anyone has information on him, would you share it with me?

Thanks

Howard