By Sam McGowan

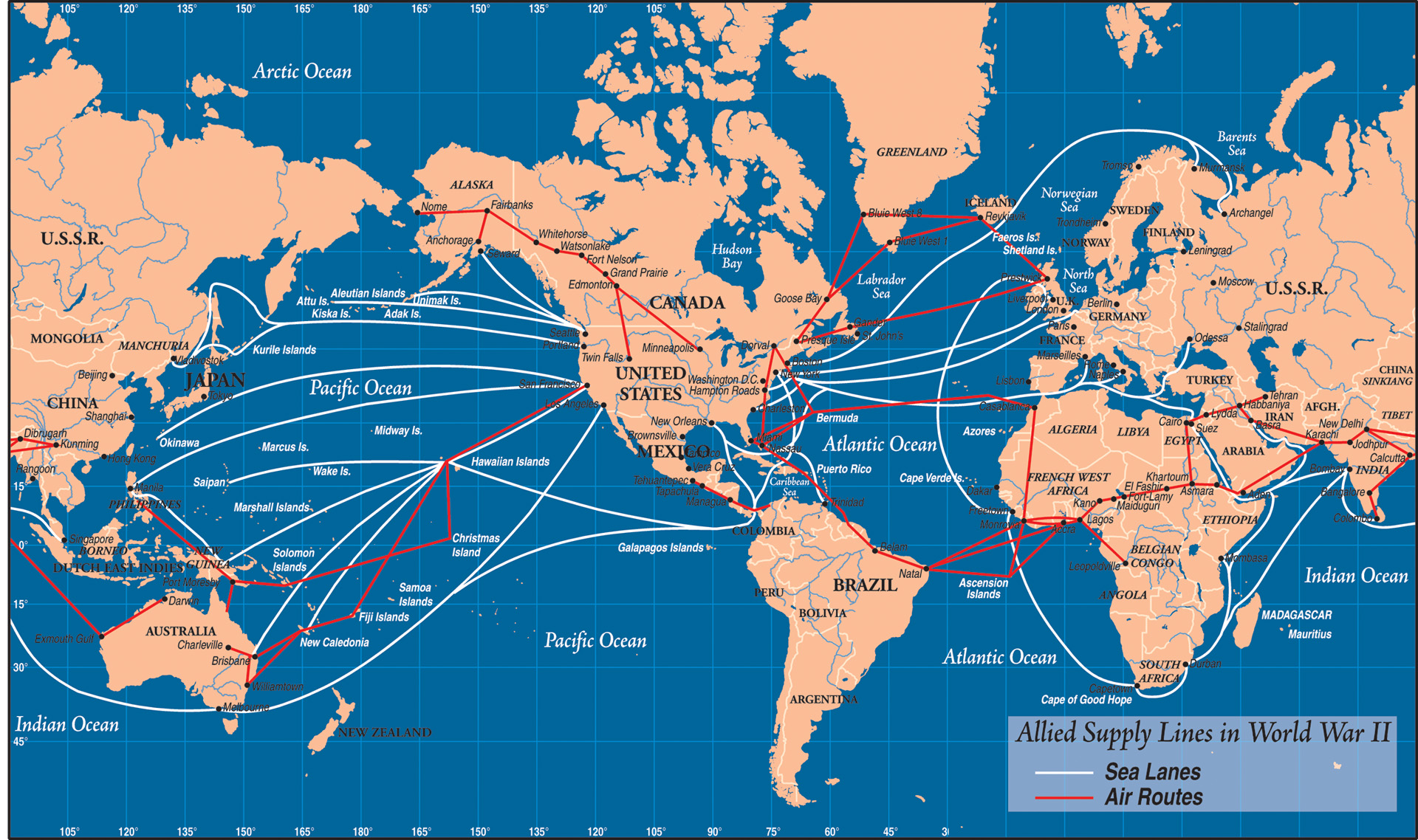

World War II was responsible for numerous technological advances, not the least of which was the establishment of the largest airline in history. While little thought had been given to using airplanes in the logistical role before the war, by the time it ended with the Allied victories in the spring and summer of 1945, the U.S. War Department was operating regularly scheduled flights to the most distant parts of the world.

Although the mission of the War Department’s Air Transport Command (ATC) was entirely logistical in nature—the crews themselves referred to the initials as meaning “allergic to combat”—the command played a major role in the resupply of overseas forces and the transportation of essential personnel.

We Deliver

The apparatus that evolved into the Air Transport Command came into being in 1941 in conjunction with the Lend-Lease Act, legislation that allowed the United States to provide military equipment to the countries that were already engaged in war against the Axis nations. While aircraft production was one thing, delivering the airplanes to the customers presented problems. While fighters and other smaller aircraft could be delivered by ship, it was more efficient to deliver transports and bombers by air. Since the military forces of the recipient nations were overburdened with fighting the war and could not pick their airplanes up in the United States, other avenues were pursued.

Overwater delivery of American-built aircraft to England began in November 1940, when a Canadian company began transoceanic deliveries of airplanes that had been flown to Montreal by factory-employed delivery pilots. But the increase in deliveries from the Lend-Lease Act would test the resources of the factory pilots severely. To cope with the problem, the Army Air Corps established its Ferrying Command on May 29, 1941, with the mission of providing Air Corps pilots to make the domestic deliveries to Canada. The objective was twofold: to give U.S. Army pilots experience in the latest combat equipment, and to release the civilian factory pilots to join the British organization responsible for overwater deliveries from North America to Europe.

Air Transport Service Is Launched With Converted B-24 Bombers

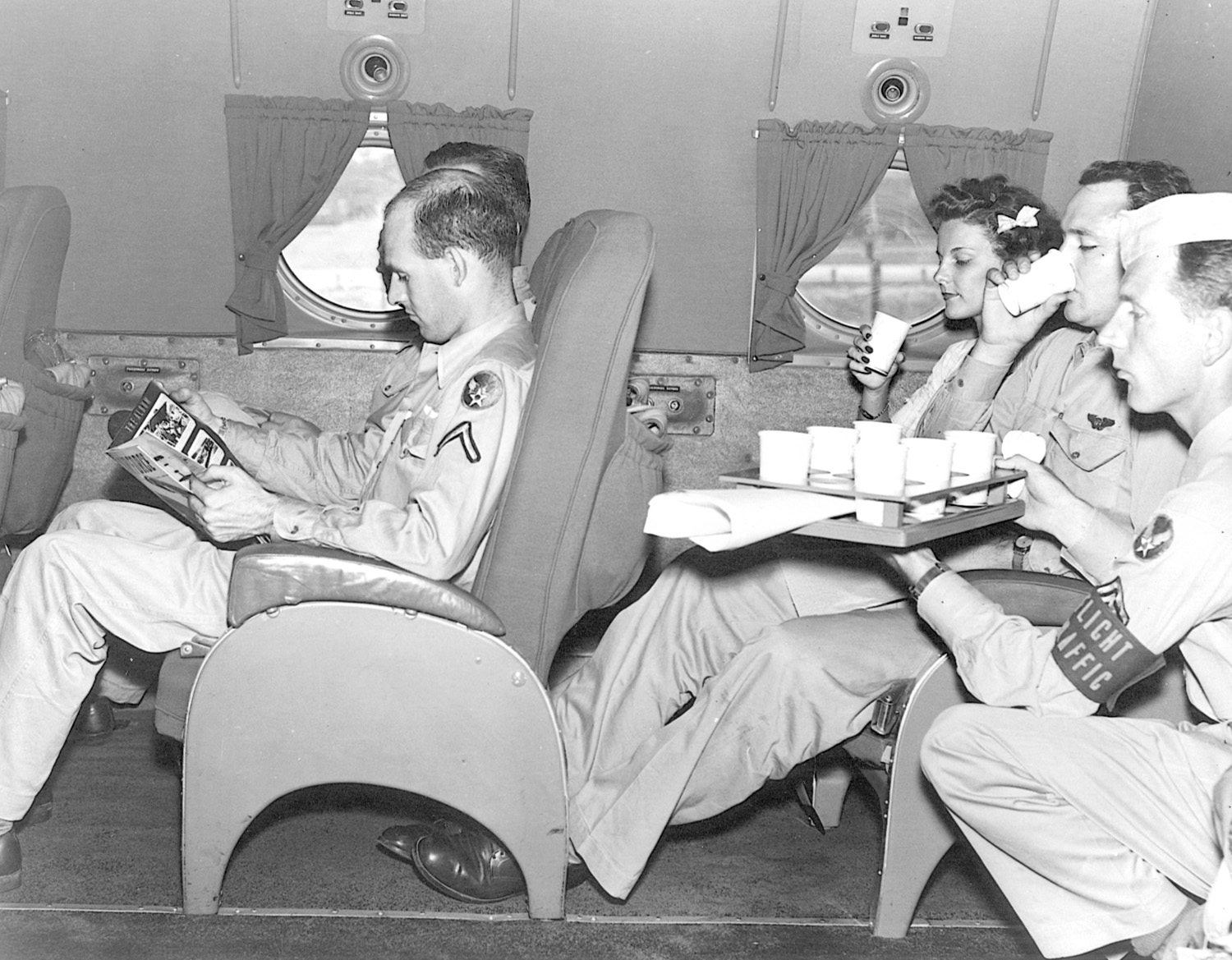

Simultaneously with the establishment of the Ferrying Command, the War Department took steps to inaugurate an air transport service between the United States and England. The new service took to the skies on July 1, 1941, when Lt. Col. Caleb V. Haynes departed Bolling Field in Washington, DC, in one of the first Consolidated B-24 bombers to be delivered to the Army. The inaugural flight was bound for Scotland by way of Montreal and Newfoundland. Soon dubbed “The Arnold Line,” the new service made an average of six round trips a month between Washington and Ayr, Scotland, until the potential for winter weather over the North Atlantic brought the mission to a halt in October. All flights were made in converted four-engine B-24s, with the passengers seated in the bomb bays.

In September the service was expanded when two B-24s flew to Moscow by way of Great Britain, transporting members of a diplomatic mission. By the outbreak of war on December 7, 1941, the Ferrying Command was operating 11 converted B-24s that had been loaned by the Army Air Corps Combat Command.

New Routes To Europe Developed

To facilitate deliveries, the Ferrying Command sought to establish new routes from the United States to the Allied nations. Since winter weather presented an obstacle for several months of the year over the North Atlantic, a South Atlantic route was surveyed and established. The route originated in Miami, then went by way of the Caribbean to British Guyana and Brazil, then over water to Ascension Island and the west coast of Africa, then overland to Cairo.

In June 1941, Pan American Airways organized a special department to make deliveries of British-purchased Douglas DC-3 transports to Africa. Flown by Pan American Airways crews, the first transports left Florida for Africa on June 21. Pan American, as well as other U.S. airlines, would play a major role in the Ferrying Command and the subsequent Air Transport Command for the duration. Under an agreement reached with the War Department and the British, Pan Am assumed responsibility for establishing ferry and air transport routes to Africa, and also for operating a trans-African transport route that had been previously established by the British. Speedy aircraft delivery from the States to British combat units in Africa was the primary purpose of the new service, with air transport of cargo and personnel secondary. As it turned out, Pan Am had only delivered a dozen airplanes, all transports, prior to Pearl Harbor.

New Flying Record Set Before America Enters War

The Ferrying Command also set up a flying-boat service to West Africa using Pan Am flying boats that had been withdrawn from Pacific service. Only one trip, a survey flight to establish the route, was made prior to December 7. In addition to the Pan American ferry service, the War Department also set up a military-operated transport service to Cairo, again using converted B-24s. Lieutenant Colonel Caleb Haynes was at the controls of the first B-24 to depart Bolling Field for Egypt, with Major Curtis Lemay in the copilot’s seat for the historic 26,000-mile flight, the first round trip over the South Atlantic to Cairo. In November, the Ferrying Command began delivery of 16 LB-30 Liberator bombers that had been slated for British use in Africa, but the American entry into the war prevented the delivery of all but four (another was destroyed beyond repair in a crash).

Immediately after Pearl Harbor, the Ferrying Command was given a part in “Project X,” the movement of a planned 80 four-engine bombers to the Far East to reinforce the fledgling air force that was fighting for its life in the Philippines. Although the airplanes were flown by crews assigned to the 7th Bomb Group, which had been in the process of moving to the Philippines when war broke out, Ferrying Command was responsible for coordinating the move and providing support while the bombers were en route. The first deliveries were to be 15 LB-30s that had been repossessed from the British at the outbreak of war. They were all scheduled to go to the Far East by way of the South Atlantic route to Africa, then through the Middle East and Pakistan.

Project X Makes Partial Delivery To Far East

While five of the L-30s followed that route, the others traversed a new airway over the Pacific. The Liberators made up the first echelon of Project X, while 65 new Boeing B-17s made up the second. Only 44 of the planned 65 bombers were delivered to the Far East. Some were diverted to India when the Tenth Air Force was formed, some were cannibalized for spare parts along the route, five crashed en route, one returned to America for repairs, and another was halted in Africa awaiting parts.

With America’s entry into the war, the need for air transportation increased dramatically. The return of Ferrying Command personnel to the United States after overseas deliveries was a major consideration, and with this in mind the command set up scheduled routes between the United States and Australia using five LB-30 Liberators that had been converted into transports. The airline was operated under contract with crews provided by Consolidated Aircraft, which had previously established a ferry route for deliveries of twin-engine bombers to the Dutch in the East Indies.

Three of Ferrying Command’s converted B-24s were taken off the Cairo run and sent to the Southwest Pacific, where they were assigned to the Allied Air Transport Command in Australia and used to transport ammunition to the Philippines and personnel throughout Asia. All three were lost within a few months, two to enemy action and one to a forced landing in the water.

Pan Am Pilots Join In To Fly The Hump To China

In the spring of 1942, 10 Pan American DC-3s were detached from the Trans-African route and sent to India to airlift gasoline and other petroleum products to China to refuel the B-25 bombers for the upcoming Tokyo mission under Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle. The B-25s failed to arrive in China intact, and the Pan American airplanes joined a small force of Army C-47s that had just arrived in India in an airlift effort in support of the retreating Allied forces in Burma. The small group of transports would make up the nucleus of the 1st Ferrying Group, which would become part of Tenth Air Force, and assume initial responsibility for air transport operations across the Himalayan “Hump” to China.

In June 1942, the War Department reorganized its air transport assets in response to a letter submitted to President Roosevelt by L.W. Pogue, the head of the Civil Aeronautics Board, in which he advocated the establishment of an independent air transportation organization separate from both the Army and the Navy. Fearful of fragmentation of the airline industry due to competing contracts from a myriad of military agencies, Pogue advocated an independent government airline that would function outside of both the War and Navy Departments.

Ferrying Command Transformed Into Air Transport Command

A second option of the “Pogue Plan” was the establishment of a War Department command to assume responsibility for all air transportation needs of the Army. Army Air Force commander General Henry “Hap” Arnold opted for the latter and issued General Order #8, which changed the Ferrying Command to the Air Transport Command. This was to be a new organization responsible for all aircraft ferrying and for all air transportation of the War Department “except those served by the Troop Carrier Command,” which was established by the same order. The duties of the Ferrying Command were assumed by the new ferrying division of the Air Transport Command. The Navy would eventually form its own air transport command.

The ATC began service with an assortment of military and civilian aircraft and crews. The civilian resources were provided on contract by the airlines. In mid-1942, and for several months thereafter, the command depended on twin-engine transports, primarily militarized DC-3s and a few converted B-24s. A handful of four-engine flying boats was operated by the U.S. Navy on overwater routes. The command’s resources were increased by the conversion of large numbers of Consolidated B-24Ds to C-87 “Liberator Express” transports, which began entering service in September 1942. With the long-range C-87s, the Air Transport Command established routes throughout the world.

New Route To Alaska Delivered Planes To Soviets

Ferrying of airplanes remained a major role of the ATC, and the Ferrying Command, commanded by Colonel, later Brig. Gen., William H. Tunner, opened and maintained additional routes. One new route went to Alaska, where U.S.-built airplanes delivered under Lend-Lease were picked up by Russian pilots. The Alaska route originated in Great Falls, Mont., and continued northwestward through Edmonton, Alberta, and on to Alaska. United Airlines also took responsibility for an air transport mission over a similar route that originated at Dayton, Ohio. While all of the routes were hazardous, the Alaska route was especially so due to the uncharted territory and the terrible winter weather.

Staffing and equipping the new Air Transport Command was a major problem, particularly since combat units were dreadfully short of both men and equipment. Prior to Pearl Harbor, the War Department had made a heavy commitment in orders for militarized Douglas DC-3s—and for the new four-engine DC-4, which was still under development—to support the Army’s new airborne forces. Several potential transport designs were put forth by various companies. The Curtiss-Wright C-46 was the design eventually selected to serve the ATC.

B-24 Conversion Provided Four-Engine Transport For Long Distances

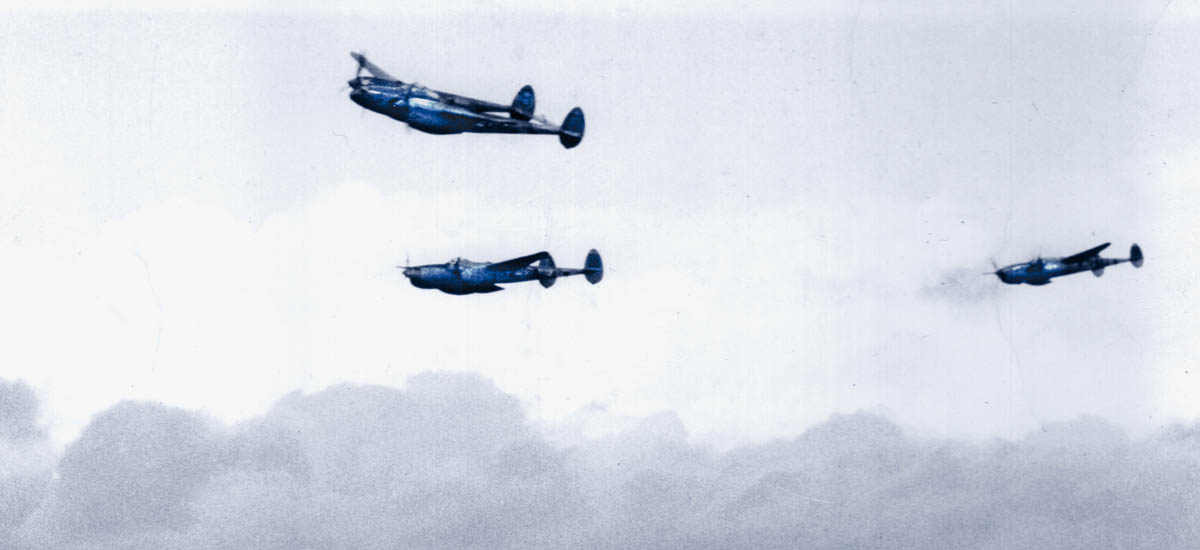

Both the C-47, the military designation of the DC-3, and the C-46 were twin-engine designs, which placed them at a disadvantage on long flights over water. Four-engine airplanes offered a safety advantage, but there were no suitable models available in mid-1942. Douglas Aircraft’s C-54, the military designation of the DC-4, was still under development and would not enter service in large numbers until 1943. The 4,500-pound payload of Boeing’s C-75 made it unsuitable for long-range transport. Lockheed offered the C-69 Constellation, but the factory’s dedication to production of the P-38 fighter restricted deliveries.

Until the C-54 could be produced, the only choice for a four-engine transport was the C-87 conversion of the versatile B-24. The factory-produced C-87 Liberator Express was capable of transporting a payload of 7,500 to 9,400 pounds over a 3,250-mile route, and was the airplane that inaugurated ATC’s long-range transport service.

Finding pilots for the Air Transport Command was even more difficult than finding airplanes. Prior to the war, the Ferrying Command had utilized combat pilots on loan from the Air Force Combat Command. Pilots served 30- to 90-day periods to gain experience in the combat planes being delivered to the British, a policy that could not continue. The outbreak of war led to a recall of these experienced pilots to their parent units as the squadrons prepared for combat operations overseas.

Commercial and Private Pilots Help Fill the Void

To meet the requirements set by the War Department, the Ferrying Command began hiring civilian pilots from the ranks of commercial and private pilots around the country. Since the airlines were mobilizing for war and were operating under military contract, the War Department looked for pilots who were not employed in airline flying or as flight instructors—bush pilots, air-taxi pilots, crop dusters, and business and pleasure pilots. Employed by the government as civilians, the pilots were given a 90-day probationary period at the end of which, if they were found qualified to fly military airplanes, they were commissioned as officers and designated as “service pilots,” then assigned to the cockpits of military airplanes.

The civil airlines were a source for approximately 2,600 pilots, many of whom were former military pilots who still held reserve commissions. But the heavy reliance on the airlines to fill military contracts prevented a wholesale callup of these men. Instead, limited callups of reserve officers from the airlines were initiated for special projects. The first was to fill out the ranks of Ferrying Command personnel responsible for moving the bombers of Project X to the Far East. A second contingent of airline reservists was assigned to Project AMMISCA, a special mission to equip an air-transport group to fly supplies into China from India. Made up of highly experienced transport pilots, the AMMISCA Project group moved to India where it was assigned to the Tenth Air Force’s 1st Ferrying Group.

Military Makes Up The Difference From Its Own Ranks

Project 32 was a Ferrying Command effort to train its own aircrews. A nucleus of pilots transferred from the Combat Command was melded with airline pilots holding reserve commissions and brand-new aircrew personnel who had recently graduated from Army Air Corps training programs. Later, Project 50 brought a contingent of airline reservists back into uniform to fly four-engine transports.

Another planned source of pilots, though it ultimately failed to meet expectations, was the Civilian Pilot Training Program. Set up before the war, the CPT was supposed to complement the military flight-training programs and to provide a source of pilots for the airlines.

In August 1942 General Harold George, the commander of the fledgling Air Transport Command, initiated the Airlines War Training Institute to supplement the CPT. General George optimistically set a quota of 500 new copilots to enter service every two months, after completing a 150-hour CPT program and an additional four weeks of training with the airlines. But results were far less than expected due to a combination of the draft, high wages in the war industries, and the best qualified men having already been recruited either by the airlines or the military. Eventually, the Air Transport Command would turn to the military itself for pilots to man its growing fleet of transports.

Experienced Women Pilots Join the WAFS

Another source was the small number of licensed women pilots in the United States. In the summer of 1942, Mrs. Nancy Love, a civilian employee of the Ferrying Division of ATC and a qualified pilot herself, suggested to her boss, Colonel Tunner, that well-qualified women should be hired as civilian ferry pilots.

The extreme need for pilots led the War Department to approve the proposal, and 25 exceptionally qualified women were hired to become members of the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron, which was based at New Castle, Del. Unlike the later Womens Air Service Pilots, commonly known as WASPs, which trained women as pilots, the WAFS was staffed by women who were already experienced aviators, each with more than a thousand hours of flying time.

The WAFS quickly proved its worth as its pilots ferried light aircraft, bombers, transports, and eventually fighters from the factories to the military depots where they were accepted for military service. Unlike the male pilots who flew overseas routes to the combat zones, the women were restricted to domestic duties. Tunner approved the use of women on overseas routes, but an inaugural mission with Nancy Love and Betty Gillies at the controls was halted in Newfoundland after the two women flew a B-17 there in preparation for ferrying it to England.

Famous Female Pilot Had Pull With Eleanor Roosevelt

Although the overseas flight was halted by order of Army Air Forces commander General Arnold, many of the WAFS believed the order was initiated by Jacqueline Cochran, a famous female pilot with ties to Eleanor Roosevelt, who had persuaded the president to authorize the establishment of the Womens Air Service Pilots. Cochran’s training program for women pilots for noncombat duties was approved shortly after the WAFS entered service.

Rather than have two separate programs for women pilots, Arnold elected to place the WAFS under Cochran’s control, though Nancy Love continued in her position as WAFS commander. A flamboyant and ambitious woman who had managed to climb above her origins as the daughter of a Florida sharecropper, Cochran was provided a Lockheed Hudson by the Army Air Forces. The purpose is unclear, but Cochran had made a highly publicized flight to England in the Hudson a few weeks before the B-17 ferry mission was scheduled, and the WAFS believed she didn’t want to be upstaged.

ATC Casualties Much Lighter Than Anticipated

Jackie Cochran’s WASPs provided some pilots for the ATC’s Ferrying Division as well as for other noncombat duties. But the WASPs were inactivated as a result of events that boosted the ranks of available pilots for the Air Transport Command. By the spring of 1944 the War Department realized that casualties among aircrews were significantly lighter than had been anticipated early in the war and fewer new pilots were needed in the combat squadrons. Consequently, the civilian-run primary flight schools around the country were being shut down and the instructors were losing their draft ineligibility status.

The former instructors were reassigned to air-transport squadrons after being commissioned and placed on flight status as service pilots. Simultaneously, large numbers of combat pilots were returning from overseas and could be utilized as transport pilots on domestic and overseas routes. The WASPs were disbanded, but the ATC found itself with the pilots it needed to man its worldwide fleet.

Most Routes Were Non-Combat—With One Exception

By definition, the Air Transport Command was not a combat command, and though the crews who flew the transports operated into hostile areas, they performed in the logistical role much the same as the behind-the-lines truck drivers who performed similar duty over the roads of the world. In contrast, the troop carrier groups were combat units whose mission was to provide air transportation for combat units in the field. The order that established the ATC separated the command from the troop carrier organizations and established a distinction between the two missions. With one exception, the ATC route structure was from the United States to overseas depots in rear areas removed from combat operations. The exception was the route from India over the Himalayas and Burma into the Chinese interior.

The airlift that came to be known as “The Hump” began under the auspices of the Tenth Air Force, the combat command responsible for air operations in the China-Burma-India Theater. China was represented in the United States by a powerful lobby led by T.V. Soong, the brother of Madame Chiang Kai-shek, who had herself been educated in the United States. China had been a symbol of Japan’s evil intentions since the early 1930s, when Japanese troops occupied parts of the vast country. Although the Japanese controlled the China Sea, supplies were delivered to the beleaguered country through Burma until it fell in the spring of 1942.

China Cut Off By Land and Sea

With the fall of Burma, China was completely cut off except through Russia to the north and by air from India to the west. Russia had declared itself neutral in the war against Japan, ruling out the delivery of war supplies from the north. With Burma in Japanese hands, the only route into China was by air.

In the spring of 1942, a flight of Pan American Airways DC-3s under contract to the Ferrying Command arrived in India. In response to the Doolittle raid, the Japanese went on the offensive in China and Burma and began moving westward toward India. The Pan American aircraft, along with other DC-3s belonging to China National Airways, a Pan Am subsidiary, were put to work transporting cargo into China.

Shortly after the arrival of the Pan American contingent, the airplanes and crews of Project AMMISCA arrived in India and became the 1st Ferrying Group, assigned to the Tenth Air Force. Their mission was to begin an airlift to China, but the military situation in the region dictated that the transport crews would operate primarily in support of British, Indian, and Chinese ground troops who were engaged in the defense of India’s Assam Valley. Ironically, Assam was the very region from which transports bound for China had to operate. The more pressing need to defend the bases prevented the transports from performing their mission of airlifting supplies to China.

ATC Takes Over Airlift After Supplies Don’t Reach China

China, however, was a political issue, and when an American “fact finder” named Frank Sinclair came back to the States to report that only a portion of the planned supplies were getting into China, the White House became concerned. Ambitious Air Transport Command staff officers seized the opportunity and proposed that ATC take over the airlift.

Sinclair’s report had stated that the Tenth Air Force lacked “singleness of purpose”—as if moving supplies into China took precedence over defending the very area from which the airlift transports operated. Influenced by outside political pressure, General Arnold agreed to transfer the airlift to the ATC. Two troop-carrier squadrons were ordered to India to take over combat responsibilities, and the 1st Ferrying Group was scheduled to transfer to ATC control on December 1, 1942.

ATC Falters On First Mission

The transfer took place as scheduled, and the Air Transport Command immediately fell flat on its face. Sinclair, who was a representative of an American civilian corporation doing business with the Chinese, had derided the Tenth Air Force for having a “defeatist” attitude. He believed that if enough airplanes were assigned to the task, supplies could get through. But Sinclair had failed to take the military situation into consideration, and when ATC took over the airlift the command suddenly found itself in the middle of a war in which air transport was badly needed to move and resupply combat forces. Instead of increasing as Sinclair and the ATC leadership had forecast, the volume of supplies moving into China actually declined during the first months of ATC operation.

ATC planned to replace the C-47s that had been the backbone of the Hump airlift with more powerful C-46s, but when Curtiss-Wright began deliveries of the new transports, they were found to be deficient. The C-46s were plagued with mechanical problems, while their fuel system was so poorly designed that a single hit from a tracer in the right place would turn them into flaming coffins.

Environmental Conditions More Hazardous Than Japanese Fighters

It was well into 1943 before the C-46s were able to assume a share of the Hump airlift. Increased tonnage capacity was supposed to be afforded by the assignment of a squadron of C-87 four-engine transports to the China airlift, but the task proved to be very difficult. To keep the transports away from Japanese fighters, the Hump route ran north from India’s Assam Valley across the lower reaches of the Himalayas, then east to Chungking. The route kept the transports out of range of Japanese fighters in southern Burma, but the higher elevations of the airfields in Assam reduced the performance of the converted bombers considerably, leading to frequent takeoff and landing accidents. Those airplanes that did manage to get off the ground with their heavy burdens were subject to strong winds, turbulence, and ice over the mountains that lay between the Indian bases and their destinations inside China.

Although the Hump airlift was in a combat zone, the real threats to the transports were accidents and poor weather. Only six ATC transports and 13 crew members fell victim to enemy action, but at least 600 transports were lost due to accident, so many that Hump veterans began to refer to the route from Assam to Chungking as the “Aluminum Trail.” Yet, in spite of the accidents, tonnage across the Hump began to gradually increase as more and more transports were assigned to the airlift.

Change of Command and Capture of Burmese Field Lead To Better Outcomes

In mid-1944 two things happened that led to a dramatic increase in tonnage airlifted across the Hump. First, Brig. Gen. Tunner, former commander of the Ferrying Command, arrived to assume command of the airlift. A West Point graduate, Tunner was more of an administrator than a general, but he had well-developed ideas related to improving efficiency. Tunner initiated procedures and policies designed to reduce accidents and improve efficiency in all facets of the operation, including cargo handling, aircraft maintenance, and aircrew procedures.

While Tunner’s new policies led to a marked improvement in efficiency, the real boon to the airlift came from the capture of the airfield at the Burmese town of Myitkyina by the U.S. troops under Brig. Gen. Frank Merrill. With Merrill’s “Marauders” in control of the airfield, troop-carrier transports could bring in reinforcements. When Myitkyina was secure, the airfield was opened up to ATC transports while the capture of the region opened up a southerly route over Burma for the C-54s, which were becoming the mainstay of the ATC force. Previously, the C-54 had been restricted from the airlift because its low operational ceiling ruled out its use over the Himalayas.

Additional tonnage capacity was afforded through the transfer to ATC of C-46 and C-87 transports and C-109 tankers that had come to the theater to support “Matterhorn,” a force of B-29s operating from Chinese bases. In early 1945, airfields for the B-29s became available in the Mariana Islands, and their departure released the dedicated transports for the larger Hump effort.

Efficiency and Tonnage Increased By Reassigning B-24s To Hump Duty

During the final months of the war, Allied commanders in the CBI came to the conclusion that the amount of fuel required to operate four-engine bombers over the Himalayas would be more efficiently used if the airplanes were hauling cargo rather than flying tactical missions against Japanese forces. Consequently, the two B-24-equipped heavy bomber groups operating in the CBI were taken off combat operations and assigned to ATC for Hump airlift duty.

With the liberation of Burma, the troop carrier and combat cargo groups that had been supporting combat operations were also reassigned to ATC to comprise a distribution system moving cargo from the bases where the four-engine transports made their deliveries to smaller fields in the Chinese interior. The additional airlift capacity allowed tonnage flowing across the Hump to increase dramatically.

ATC Provided Much More Than Transport Services

The Hump airlift is the most famous of the ATC operations of World War II, but in reality it was only a portion of the overall air transport effort. The movement of aircraft overseas to combat units as well as to U.S. Allies remained a major mission of the ATC throughout the war. While ferrying division crews moved large numbers of fighters and bombers from the factories to the combat zones, they were also responsible for the movement of aircraft flown overseas by combat crews. Combat crews bound for Europe or Asia picked their airplanes up at the depots where they were made ready for combat, then entered the ferrying division system, which coordinated their movement and provided weather and communications services as well as quarters and other support along the way. ATC also provided Air/Sea Rescue services to search for any crews that might be lost along the delivery routes.

Photographing ATC Routes Presaged Google Maps

By mid-1943 Air Transport Command had established a route structure that literally covered most of the world. In June, Ivan Dmitri, a photographer of renown, left Miami to cover the ATC system. The product of his three-month journey was published in a book entitled Flight to Everywhere, an exercise in photojournalism that demonstrated that the ATC had a presence throughout Africa and the Middle and Near East all the way into China. Dmitri’s journey originated in New York, then went south to Miami and on to Natal, Brazil, then across the Atlantic to Ascension Island and on to Africa. He went to China, returned through Libya and North Africa, then flew north to Scotland and across the Atlantic to Iceland and Newfoundland, before returning to New York from a journey that was made entirely on ATC transports. The skilled photographer produced a record of ATC operations and of elements of the war effort at the bases he visited.

Cargoes transported by ATC included everything, even the kitchen sink, though the real value of air transport lay in the delivery of crucial items needed by the combat commands. Dmitri’s journey placed him at Benghazi, Libya, at the time of Operation Tidal Wave, the daring and dangerous low-level bombing mission against the Ploesti oil refineries by Eighth and Ninth Air Force B-24s. Dmitri related how a special airlift of C-87s brought a supply of Pratt & Whitney engines to Benghazi to replace those that had been shot up or worn out on the dramatic mission. Other emergency airlifts transported artillery fuses to North Africa and hand grenades to New Guinea—just about anything that suddenly became in short supply and could not wait for the long shipboard journey to the combat zones.

Birth Of Military Medical Transports

During the battle for Papua, New Guinea, the air evacuation of casualties from the battlefield to rear-area hospitals became a normal mission for troop carrier crews. It was only natural that the long-range transports of the Air Transport Command would also be utilized in the air evacuation role. Still, it was not until the spring of 1943 that ATC transports became involved in hauling patients, most of whom were transported from one overseas base to another.

Early in the effort, most patients originated within the Alaska Wing, though by 1944 the CBI was accounting for the largest share of patient load. However, few of the CBI patients were airlifted out of the theater. Most were carried within the region and, by rights, should have been transported by troop carrier units. The C-54 became the standard aircraft for patient transport as it was the only ATC airplane actually suited for the role. Airplanes were converted for the air evacuation role on a gradual basis, with the Pacific air-transport wings being the first to convert more than 10 airplanes into air ambulances. Still, in 1944 no less than one-fifth of all patients—31,771— transported to the continental United States returned aboard ATC transports. In 1945, the number more than doubled as 86,407 patients were transported back to the United States by Air Transport Command.

Air/Sea Rescue and aviation weather reconnaissance were other functions that developed within the ATC, though they were developing simultaneously among the combat commands as well. The overseas ferry and transport routes transited some of the most rugged terrain in the world, as well as vast reaches of the world’s oceans. The distances were such that the survival of the crew and passengers of a transport that was forced down depended largely on their being found by an air/sea search. Air Transport Command equipped Air/Sea Rescue units with single-engine UC-61 “Norseman” transports and specially configured C-47s to conduct aerial searches for overdue aircraft, particularly along the Alaska ferrying route, which covered the wilds of western Canada and Alaska.

Blackie Porter Leads Daring New Rescue Service

The unique situation in the CBI led to the establishment of a different kind of rescue service. In 1943, Captain John E. “Blackie” Porter organized an ad hoc rescue unit to search for downed airmen on the Hump route from India to China. Flying a modified B-25 and armed C-47s, Porter led search and rescue missions over the rugged Himalayas and steaming Burmese jungles. A former stunt pilot, Blackie Porter was a colorful character noted for his daring, and his men came to be known as “Blackie’s Gang.” Blackie lost his own life when his B-25 was attacked by Japanese fighters while on a mission close to enemy territory.

One of the greatest benefits of the Air Transport Command was the establishment of a worldwide presence for the United States in regions where few Americans had set foot prior to 1941. The ferry and transport routes literally covered most of the globe, and at stops along the way the Army set up staging stations manned by dispatchers, weather observers, and communications personnel. The ground personnel provided a worldwide dispatch and communication system that would serve to modernize the postwar civilian airline industry.

Political and Military Friction Emerges

Although the Air Transport Command was established as part of the U.S. Army, it was not a combat command, which led to a lot of friction between ATC personnel and men assigned to the combat commands. This was particularly true in the CBI, where ATC transports operated over essentially the same routes as bomber groups that were responsible for much of their own supply to their forward bases in China, and where troop carrier and combat cargo groups were airlifting vast amounts of cargo and personnel from India into Burma in support of combat operations.

Morale was low in the ATC squadrons in India, and to counteract the problem the ATC leadership began publicizing the role of the Hump airlifters, to the point that airlift in the CBI came to be associated exclusively with the Air Transport Command in the public eye. The friction was enhanced due to the political aspirations of some of the ATC leaders, who were looking forward to a postwar role for the new command. Whether ignorant of the difference between logistical and combat airlift or ignoring it, men such as General Tunner often made claims that there was no difference between the two, and that all air transport should fall under the auspices of the ATC.

The friction between ATC and the combat units in the CBI led to major problems in early 1945 when heavy bomber and troop carrier groups were assigned to augment the ATC. The decision to augment ATC’s C-54s with B-24s and troop carrier C-47s came about as a result of the ATC’s failure to meet its allotted goals.

All In On The Hump At War’s End

With the fall of Burma into Allied hands, the tactical goals for the Tenth Air Force had been met, so General George Stratemeyer elected to reassign the tactical units to Hump operations. The combat crews were not happy about the new assignment and became incensed when they learned that General “Tonnage” Tunner had imposed a week of special training flights on them in preparation for Hump transport operations. In spite of the friction between the combat crews and the ATC personnel, the combat units pitched in and began hauling ever-increasing amounts of cargo across the Hump into China.

The final effort over the Hump brought the Air Transport Command’s wartime mission to an end, though ATC and other transport operations would continue all over the world in support of the demobilizing U.S. military and the rebuilding of nations torn by war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments