By Arnold Blumberg

From the late 3rd century bc to the 3rd century ad, Roman troops on campaign built a defended camp at their resting place each night. Carefully detailed and prearranged in their location and manner of construction, these bivouac marching camps were made to accommodate the headquarters, personnel, animals, baggage, and camp followers of whatever military-sized formation was to be housed within. Today, a camp of this nature is referred to by historians as a Roman marching camp.

Nowhere in the annals of warfare up to the time of the Romans is there recorded such an extensive use of fortified positions. Very seldom does the literature of the classical Greeks mention camps. Xenophon describes the camps of the Lacedaemonians as being maintained in good order and made circular when the terrain permitted. He does not indicate, however, whether they were regularly fortified. Even in the case of Alexander the Great and his successors, the strengthening of a camp is only touched upon under special circumstances, the implication being that it was not done otherwise. Supporting this contention is a passage by the ancient historian Polybius expressly stating that the Greeks, in order to save themselves the trouble of entrenching, sought out terrain with natural protection for their campsites.

Even the Romans did not employ fortified camps during their expansion on the Italian peninsula between 389 and 281 bc. It was not until they encountered King Pyrrhus of Epirus and his Macedonian-type phalanx and Thessalian and Epirote cavalry that they started to rely on marching camps as a protective device.

How the Roman Marching Camp Was Born.

Harried on the march by Pyrrhus’s superior performing cavalry, and defeated by the Greek king first at the Battle of Heraclea (280 bc) then at Asculum (279 bc), the Romans hit upon the idea of creating a safe, fortified fall-back position in case of defeat or a need to reorganize. Thus the Roman marching camp was born. The ancient Roman historian Frontinus claims the design was adopted from the one Pyrrhus used to house his army while in the field against the Romans. Regardless of its origins, the Romans used it to good effect in their next contest against Pyrrhus. In 275 bc, on the Arusian Plains near the city of Beneventum, a Roman army under M. Curius Dentatus decisively beat the Greeks in a seesaw combat using an entrenched camp as both a strongpoint and rallying area. It was soon after this important fight that all Roman forces on active service regularly built such facilities after each day’s movement.

The marching camp, according to some modern military historians, deprived classical Roman armies of the mobility by which they needed to bring an enemy force to bay and defeat it. To 20th-century scholars like J.F.C. Fuller and Liddell Hart—early proponents of rapid and sweeping wars of movement—the practice of entrenching each day during a campaign prevented the Romans from achieving that measure of maneuvering that would allow them to place themselves into advantageous positions to fight their enemies at a time and on ground of their own choosing. In essence, as far as Fuller was concerned, marching camps reduced Roman warfare to such a torpid pace that it became no more than “mobile trench warfare.” As a result, not only would the Romans be at a tactical disadvantage on the battlefield, but they would be reduced to always assuming the strategic and operational defensive.

The study of Roman warfare, however, refutes Fuller’s and others’ conclusion that the marching camp was a mill stone around the neck of any Roman military force that automatically tethered it to a strictly defensive posture.

A Pre-Arranged Display of Massive Military Power

Strategically, Roman marching camps proved to be an aggressive military instrument. They were specifically designed for operations deep in enemy territory. Their standard pattern, which varied according to the size and type of force it accommodated, was highly intimidating to an opponent. Regimented in appearance and construction, each freshly made camp marked the progress of the army and emphasized the relentlessness of its advance. The army’s action in building them eroded the enemy’s morale even before any fighting had taken place. In short, marching camps were a pre-arranged display of massive military power. Further, these camps, left in the wake of a military advance, served as a series of stepping-stones that acted as bases for the army and sustained its movements.

Marching camps, of course, were also of strategic defensive value. They were vital to the control of conquered land. Having been originally built on defensive ground, many were transformed from temporary entrenched sites into permanent fortified positions. As such, they became not only centers of territorial administration but also troop staging areas and strongpoints protecting vital lines of communications.

In the tactical realm, marching camps were essential to the success of Roman military campaigns in a number of ways. As a medium of protection they granted the troops who sheltered in them a psychological reassurance. The late 4th-century Roman military commentator Vegetius wrote in Epitome of Military Science that a camp “gave the soldiers a place of safety … as if they were carrying a walled city with them.”

How Marching Camps Were Used Both Offensively and Defensively

During battle, marching camps were employed both offensively and defensively. Offensively they acted as staging areas and jumping-off points for assaults. Defensively they were a secure base and rallying area around which an army could retreat to safety.

Both purposes of the marching camp in battle were illustrated clearly during the Battle of the Sambre River in 57 BC between a Roman army under Julius Caesar and the Belgae tribes and their allies. This combat, which took place in what is now southern Belgium, witnessed a surprise attack by the Gauls against the Roman camp. Thrown into confusion by the initial on-rush of the Gauls, the legionaries were able to sort themselves out and recover their composure by using their marching camp as a protective screen guarding a flank and their rear. They then went on the attack, pivoting on their camp and routing their foe.

Marching camps also acted as a force multiplier. An illustration of this is seen during the Gallic Revolt of 54 bc. Rushing to relieve a besieged Roman garrison, Julius Caesar with 7,000 men tricked an army of 46,000 Gauls into attacking him. He did this by constructing a marching camp that would normally hold a much smaller Roman contingent. Thinking the Romans holed up in the camp were only a fraction of their actual numbers, the Gauls marched on the site. From the bivouac Caesar unloosed his troops on the enemy from the camp, flanking and then routing them.

Marching camps could be used as staging areas for surprise attacks as well. This was accomplished by Caesar’s principal lieutenant in Gaul, Labienus. At what is now Trier, Germany, Labienus unleashed a double flanking attack against the army of the Treveri. He sent his cavalry storming out of the front and rear gates of the compound on a devastating charge that killed the rebel leader and caused the collapse of the Gallic uprising near the Rhine River in the autumn of 54 bc.

Roman Artillery Effective Before, During, and After Battle

During combat between opposing forces the Roman marching camp could serve as a defensive or offensive fire-support base for friendly troops. Ancient artillery, in the form of arrow-firing ballista and stone-tossing catapults of various sizes, was regularly carried into battle and positioned in the field or in entrenched positions. These batteries of early missile-throwing weapons were effective at hundreds of yards, and since most armies arranged themselves and their camps no more than two miles from enemy forces and positions, Roman artillery could be very effective before, during, and after a battle. This was seen time and again during the Roman Civil Wars of 49 to 45 BC when huge numbers of camps and entrenched positions were built by the different factions. Many of these fortified lines/camps were only a few dozen yards from those of their opponents and maintained by them for long periods of time.

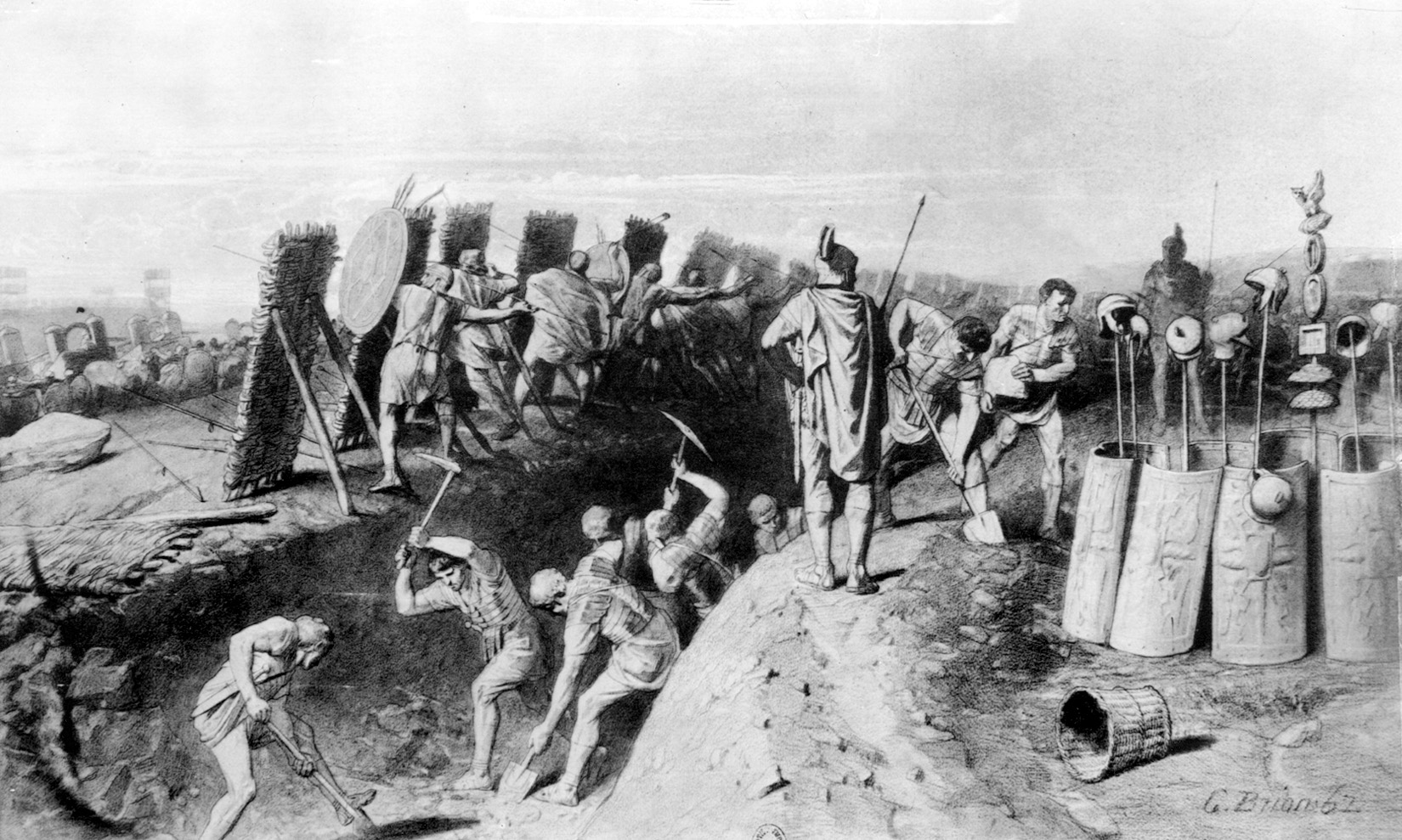

At the conclusion of each day’s march, legionary troops on the move were assembled at a site carefully selected at the day’s start. For the next three hours or more, they were put to work digging a perimeter ditch, erecting a rampart, and assembling a palisade with prefabricated materials. Polybius wrote that the standard Republican-era design was in the shape of a square, but always had to conform to the lay of the land and the numbers of men and animals to be quartered in the camp. Many of the camps excavated in the last century, especially in Great Britain, reveal straight sides with rounded corner angles.

Vegetius wrote that the camps should be constructed taking into account the configuration of the ground. He warned that a secure marching camp must be placed near a source of plentiful water, wood, and forage and not be overlooked by higher ground.

The Camps Are Erected “With Little Loss of Time”

Polybius described the drills by which the camps were erected: “One of the Tribunes and those of the Centurions … go ahead to survey the whole area where the camp is to be placed. They begin by determining the spot where the consul’s tent should be pitched … and on which side of this space to quarter the legions. Having decided this, they first measure out the area of the praetorium, next they draw the straight line along which the tents of the tribunes are set-up and then the line parallel to this, which marks the starting point of the encampment area of the troops.… All this is done with little loss of time and the marking out is an easy task, since all the distances are regulated and are familiar. They then proceeded to plant flags … [marking out the camp].”

The teams responsible for the layout of the camp were 10-man detachments, corresponding to a color party in today’s military parlance. Each century of the army on the march would designate a color party for the assignment. Each detachment was commanded by a senior tribune or a centurion. Usually these groups moved with the army’s vanguard and carried with it all the “instruments for making out the camp-site.” Included in this equipment would be a variety of colored flags or pennants used to identify the various segments of the camp.

The outline of the camp was usually marked by a ditch, with the resulting spoil used to make a rampart thrown up on the camp’s inner edge. This was then reinforced with earthen sod and strengthened by palisades. The latter items were fashioned from local timber or stakes carried by the troops. Vegetius notes that the average camp ditch was five feet wide and three feet deep. Josephus, the historian of the Jewish War (ad 66-73), mentions that the soldiers who created the camps used saws, axes, sickles, chains, ropes, and baskets in their construction and that each worker carried one of each of these tools.

The camps were usually square or rectangular and had four gates with the commander’s tent placed in the center. The camp streets were arranged in definite lines, and coded symbols showed directions to each avenue, storage area, stable, cooking house, etc., on the site. Assembly points for the different legionary infantry cohorts, cavalry tumas, and auxiliary troops were also marked. When a camp was being constructed out of reach of an enemy, the entire force, except for a small picket, would participate in the building process. When the enemy was near at hand, the precaution was that half the infantry and all the cavalry would be drawn up in battle order to guard the workers building the camp. The first legion on the scene would take up defensive positions and the actual work on the camp would not begin until the arrival of the next legion in the line of march.

Did It Take 2,100 Men To Construct Caesar’s Camp?

A good example of the size of a marching camp can be gleaned from the research done on Caesar’s camp constructed just before the Battle of the Sambre River in 57 bc. Researchers have concluded that the site, used to accommodate eight legions and other troops with Caesar, was a 160-acre square, i.e. 774,000 square yards or half a mile (880 yards) on each side. Using these figures, the surrounding ditch would have been five feet wide, three feet deep, and 10,560 feet around. Experts believe that it would have taken 3,200 to 5,600 man hours of work, depending on the condition of the soil, of over 2,100 men to complete the task.

The rampart of a marching camp was constructed about 200 feet from the lines of tents. This arrangement placed the soldiers’ tents out of range of hand-held missile-firing weapons. The cleared portion served as a pathway around the camp as well as a place to position the army’s artillery.

Although, as noted, critics of the marching camp have contended that this “pick and shovel” mindset retarded Roman operational mobility, the facts do not bear this out. The average day’s march of a legionary army was 20 miles, a rate as good as any foot-propelled military force in ancient or modern history. Pitted against another Roman army, like those during the Civil Wars, this rate was not a disadvantage because both forces moved the same distance during the same time and most of the battles were set-piece affairs welcomed by each side. Against the barbarian enemies the Romans faced in Gaul, Britain, and Germany, the Roman rate of movement proved far superior. Gallic and Germanic war bands did not just consist of mounted and foot soldiers; women, children, wagons, and livestock herds traveled with the fighting men. Columns miles long would allow only a three- to nine-mile march a day, punctuated by days of needed rest. This chronic barbarian condition made it possible for Caesar to intercept his enemies during the Gallic Wars with little trouble, or evade them when going to the rescue of friendly forces. The race to catch the Helvetii in 58 BC and the relief of Cicero’s beleaguered camp in 54 bc are good examples of the former and latter propositions, respectively.

That the Roman marching camp was a formidable bastion is borne out by the fact that none ever fell to the enemies of Rome during the Gallic Wars, and the only major one that did during the Civil Wars—Pompey’s camp at Pharsalus—was abandoned after the battle, not stormed by Caesar’s troops.

Livy, a chronicler of Roman history, wrote that Rome was able to defeat its enemies and create an empire because of virtus, opus, arma (courage, work, and weapons). The opus—the burdensome and thankless repetitive digging of marching camps—played no less a part in Rome’s martial achievements than did her courage and arms.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments