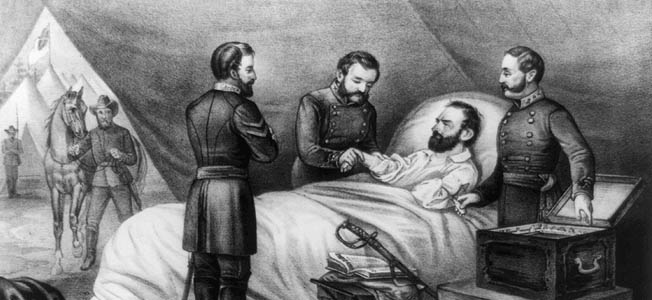

Following his greatest victory, at the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson was scouting ahead of the lines with members of his staff when tragedy struck. In the pitch blackness of the early spring evening, Jackson and his men were mistaken for Union cavalry and fired upon by their own side. Jackson sustained a severe wound to his upper left arm, necessitating amputation. Upon hearing the news, victorious General Robert E. Lee remarked, “He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right.” Lee’s words proved prophetic. Eight days after the amputation, Stonewall Jackson was dead.

Dr. Hunter McGuire, medical director of the Confederate Army II Corps believed that pneumonia was the cause of Jackson’s death, along with the general’s other attending physicians. However, modern-day analysis raised the more likely possibility of pulmonary embolism. The source of Jackson’s so-called “pleuro-pneumonia,” as McGuire put it, was presumed to be a lung contusion incurred during Jackson’s fall from a litter after leaving the battlefield at Chancellorsville. However, from the distance of a few feet at most, the ribs would have absorbed most of the force of the fall, protecting the underlying lung. There would also have been external evidence of trauma such as bruising in an injury serious enough to result in a lung contusion. Neither McGuire nor the other physicians found any evidence of such trauma.

[text_ad use_post=”455″]

Pleuro-pneumonia is a medical term that is rarely used today. Pleurisy occurs when inflammation involves the pleura, or outer surface, of the lung. Pleuritic chest pain often accompanies pneumonia, thus the term pleuro-pneumonia. Sir William Osler’s 1892 edition of his classic textbook, The Principles and Practice of Medicine, states: “Pneumonia is a self-limited disease, and runs its course uninfluenced in any way by medicine. It can neither be aborted nor cut short by any means at our command.” Osler went on to say that “the first distressing system is usually pain in the side, which may be relieved by local depletion—by cupping or leeching.” Such treatment was used unsuccessfully on Jackson.

Did Jackson Die of Pneumonia?

According to the thinking of the day, Jackson’s clinical presentation fit with pneumonia. His physicians cannot be faulted for their diagnosis or treatment, although it should be noted that 19th-century physicians were adept at eliciting the subtle physical signs of pneumonia, such as hearing a cracking sound in the lungs with a stethoscope or finding dullness to percussion of the chest. Neither of these classic signs of pneumonia was found by any of Jackson’s doctors.

In terminal pneumonia, the clinical course typically goes from bad to worse. But in Jackson’s illness, there were two distinct, sudden episodes of deterioration. These occurred on May 3 and May 6, and both were described as being associated with the onset of acute chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and perhaps fever. These symptoms are consistent with pulmonary emboli, which are blood clots traveling to the lungs. Among the numerous complications following amputation of an extremity are nonhealing of the stump, infection, and thromboembolism, or the formation of a blood clot within a large vein. According to McGuire, Jackson’s wound appeared to be healing properly and infection did not seem significant.

It is known today that an amputee is at significant risk for venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism. Immobilization of the patient following surgery can allow the blood to pool and clot within the veins. More dangerous is the formation of clots in the large veins that are tied off during amputation. The tying off of the veins, or ligation, leads to stagnation of blood in the veins, which leads in turn to a thrombus, or clot, which can then travel to the lungs and kill the patient.

Even with today’s advanced technology, it is estimated that as many as half of all pulmonary emboli go undetected by physicians. The current treatment and prevention of thromboembolism is accomplished by the use of blood-thinning agents such as Heparin and Lovenox. Although Stonewall Jackson’s death was unpreventable, given the state of medicine at the time, it is more likely that he died from thromboembolism as a direct consequence of his wound and amputation, than from the indirect cause of pneumonia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments