By Eric Niderost

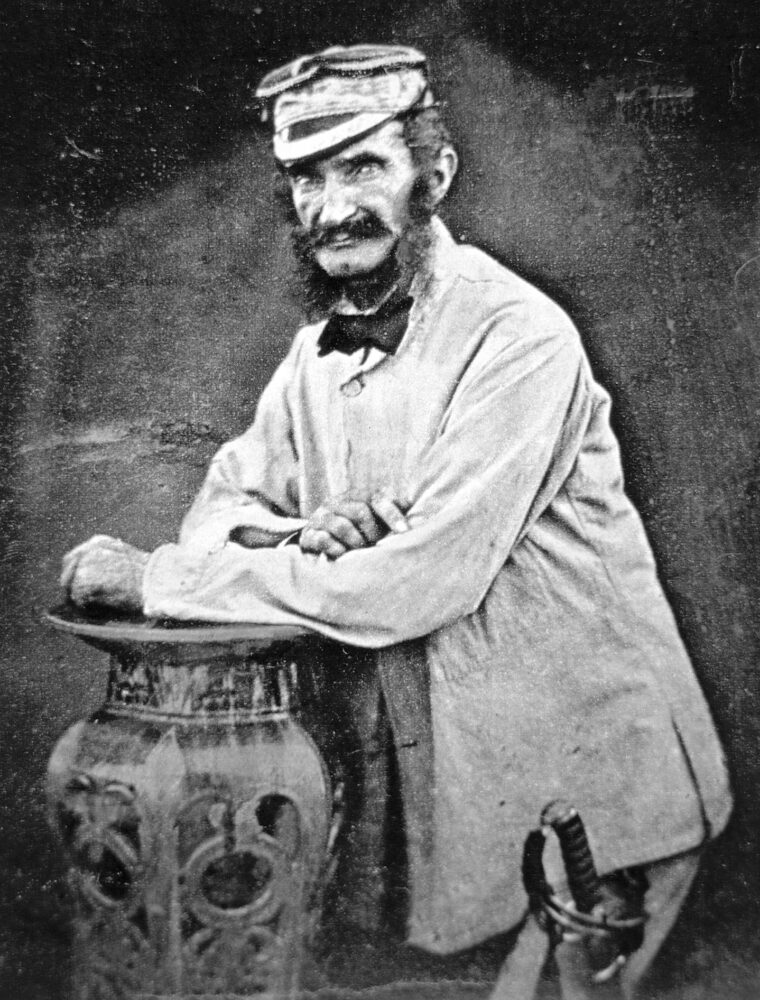

On June 26, 1858, crowds packed the narrow streets of Tianjin to witness an awesome spectacle: A British diplomat was about to sign a treaty between his country and China. The British envoy was James Bruce, the eighth Earl of Elgin, a somewhat stocky individual with a round head, bald pate, and florid complexion. The white fringe of hair that still clung around his head was joined by an impressive set of muttonchop whiskers, as if to compensate for the baldness. Altogether this somewhat cherubic individual seemed the very personification of John Bull.

Opening Trade & Allowing The Opium To Flow

Lord Elgin was accompanied by a large retinue, as befitted a representative of Her Britannic Majesty, Queen Victoria. Red-coated Royal Marines marched in serried ranks, a military band provided music, and diplomatic staffers dripped epaulettes and gold braid. Evening was approaching, and after sweating for days in Tianjin’s oppressive heat it was hoped darkness would again provide a measure of relief. It was a vain hope, as temperatures hovered around 90 to 96 degrees Fahrenheit even in the shade.

The procession reached the Temple of Oceanic Influences, where the Treaty of Tianjin was going to be signed, and the ceremonies began. Lord Elgin and high-ranking Mandarin officials duly signed the pact, which according to Chinese reckoning occurred on the 16th day of the fifth moon in the eighth year of the Xian Feng Emperor. “Xian Feng,” which meant “Universal Plenty,” was the Emperor’s reign title, not his personal name. In the summer of 1858 similar treaties were signed with the representatives of the United States, France, and Russia.

The envoys later met in Shanghai to hammer out treaty specifics. The treaty was a far-reaching document that opened 10 new ports to foreign trade, allowed foreign travel into the interior, and permitted Catholic and Protestant missionaries to spread Christianity without interference. Although not a top agenda item, the importation and sale of opium was legalized, a provision that exposed many more Chinese to drug addiction and a lingering death.

Chinese Draw The Line At Allowing Envoys To Reside In The Capital

But the government seemed most anxious about the issue of diplomatic representation in Beijing. The Treaty of Tianjin expressly permitted the permanent British envoy to the Imperial Court to reside in the Chinese capital. Chinese representatives at Shanghai did all in their power to get Elgin to reconsider the point. The Imperial Government was just now trying to suppress the Taiping rebellion, a social and political revolution that threatened not only to topple the government but to overturn China’s ancient Confucian-based way of life. If they allowed a foreign envoy in Beijing, it would cause the Qing dynasty to lose face in the eyes of the people.

Worn down by reasoned arguments and humble entreaties, Elgin backed down. The principle of diplomatic representation in Beijing remained intact, but in practice the British envoy’s permanent abode would be in Shanghai. It was agreed by all parties that one year hence the British envoy would be received in Beijing, not to stay but to formally ratify the treaty. The other Western powers made similar arrangements.

The bitter wrangling over representation exposed deep cultural misunderstandings between the Chinese and their unwanted Western guests. The Europeans and Americans wanted the Chinese to accept the normal standards of international relations, standards that were completely alien to the Chinese mind. Simply put, if the emperor allowed foreign missions in Beijing he was openly acknowledging their equality with China.

Refusing To Acknowledge Foreigners As Equals

To the Chinese, China was Zhongguo, the “Middle Country” or “Middle Kingdom,” center of all human civilization. All else was on the periphery, and scarcely worthy of notice. Foreigners were barbarians, uncouth savages that the Chinese treated with a mixture of condescension and contempt. In the Chinese world-view the “outer barbarians” came as supplicants offering tribute, not trade. Trade implied equality, and China had no need for Western “trinkets.” Emperor Quan Long, one of the Qing dynasty’s greatest rulers, wrote Britain’s King George III in 1793 that “I set no value on objects strange and ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures.”

If the Chinese had grown complacent and culturally arrogant, there were sound historical reasons for this frame of mind. China possessed a civilization five thousand years old, and was long accustomed to political and cultural dominance. It was easy to think in feudal terms, because China was the overlord of many Asian states. Around 1800 the Middle Kingdom’s vassals included Annam (Vietnam), Choson (Korea), and the Ryuku Islands. Sometimes the control was only nominal, yet in sending tribute to Beijing rulers acknowledged China’s pre-eminence.

China Turns A Blind Eye To Global Change

The feeling of cultural superiority and the “barbarian” mentality blinded the Chinese and their Qing dynasty overlords to the profound changes that were occurring in the 18th and 19th centuries. In Europe the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, stimulating commerce and prompting an aggressive search for new markets. Great Britain, as the leading industrial power, was busy building an overseas empire that was soon to make it the most powerful nation on earth.

Britain wanted to expand its China trade, looking on the Middle Kingdom’s four hundred million people as a vast undeveloped market for British goods. Besides, the British people had developed a taste for Chinese porcelain, silk, and especially tea. But the Chinese people were largely self-sufficient, and had little need for Western products. However, the British had found for their Indian-grown opium a ready market in China, and cynically expanded the trade in defiance of Chinese law.

When It Came to Opium, Profits Trumped Morality

Opium addiction spread like a plague, and in the 1830s it is estimated that about 1 percent of the Chinese people—about four million—were opium addicts. Some Britons were troubled by the opium trade, but by and large profits triumphed over morality. When the Chinese authorities tried to stop the opium trade the result was the First Opium War (1839-1842). China suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of Great Britain. The resulting Treaty of Nanjing forced China to open five ports to Western trade. Hong Kong island was also ceded to Great Britain and was proclaimed a Crown Colony in 1843.

The First Opium War should have been a wake-up call for the Chinese, a warning that their years of relative isolation and pre-eminence were drawing to a close. Spurred on by the Industrial Revolution and their own acquisitive natures, the Western powers set out to conquer the world—if not politically, at least commercially, though the two often went hand in hand. If China failed to recognize this new aggressive West, it did so at its own peril.

British Envoy Insists On Ratifying the Treaty In Beijing

In June 1859 a British mission of one battleship, two frigates, and a number of gunboats hove to off the mouth of the Hai River in northern China. Frederick Bruce, brother of Lord Elgin and new British envoy to the Dragon Throne, was aboard HMS Magicienne ready to sail up the river to Beijing. Bruce’s instructions were clear: Although he was to have his permanent residence in Shanghai, the ratification of the Tianjin treaty was to take place in Beijing. Shortly after his arrival at Shanghai in May, Chinese officials politely suggested that the ratification take place there. Bruce would have none of it. In his mind, British prestige demanded a triumphal entry into Beijing.

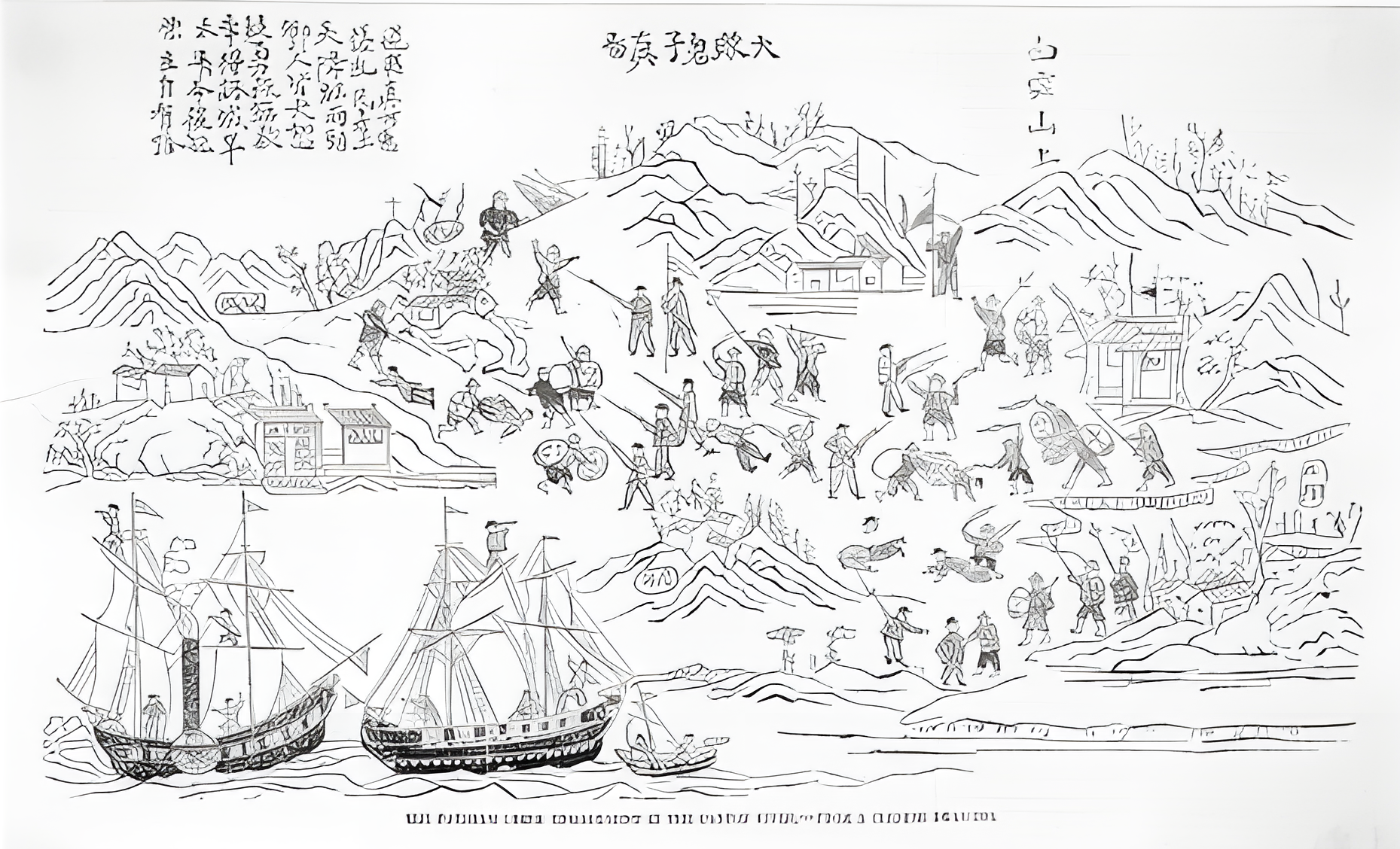

The Hai River was guarded by a series of forts that clustered at its northern and southern shores where its mouth emptied into the Gulf of Bo Hai. In addition, a series of booms stretched across the river to bar the passage of any unwanted vessels. Military concerns were the province of British Rear Adm. James Hope, a pugnacious old salt with an ill-disguised contempt for Chinese fighting qualities.

When Hope sent messages ashore requesting the booms be removed, he was met with a stony silence. The Dagu forts that guarded the river mouth were there for a reason—they were the Chinese capital’s first line of defense. The Hai River was a watery finger that thrust into the north Chinese heartland and led to Beijing itself.

The Chinese Offer A Compromise

Brushing aside Chinese sensitivity, Hope grew impatient when the booms were not removed, and asked permission to break through by force. Bruce readily assented, beginning a chain of events that was to lead to disaster and another China war. The admiral decided on a frontal assault, even though he lacked adequate intelligence about the area and he was basing plans on an incomplete map. The water at the river’s mouth was shallow, precluding the use of larger ships. Hope didn’t even know where the high-tide line was, a crucial piece of information, because when the waters receded his gunboats might well find themselves literally high and dry on exposed mudflats.

About 9 am on June 25, 1859 two Chinese junks made contact with British Minister Bruce aboard the Magicienne. They brought fresh supplies and a message from a local Chinese official who suggested a compromise: Why not land at Beidang, about eight miles farther north? If the British envoy landed there, and proceeded to Beijing by land, he would be accorded all due honor and respect. But Bruce would have to leave most of his retinue behind, making a grand entrance all but impossible.

The proposal was unacceptable to Bruce, who didn’t relish the thought of going to Beijing by the “back door,” no matter how well he was received. Still, the Chinese message suggested the possibility of compromise—but Admiral Hope’s attack was due to start at 10 am, scarcely an hour hence. Hope was a plodding, methodical man, and there was a chance the attack would experience delays. If so, a timely message from Bruce might halt operations. But the British minister decided to let the matter stand; the assault would proceed as planned.

Booms’ Iron Spikes Designed To Puncture Hulls

The river booms were made of wood cross-lashed together to form a solid mass 120 feet wide and three feet deep. Each boom was studded with iron spikes that threatened to puncture the hull of any unwary vessel. Some accounts suggest only the first two booms were wooden, while the others consisted of chains and cables.

The British had 11 gunboats at their disposal. Each gunboat was armed with four to six guns and had a complement of 40 to 50 men all told. Gunboats assigned to the attack included Opossum, Lee, Haughty, Plover, Kestrel, Cormorant,and Duchala. Opossum took the lead, moving off to ram the first boom at about 2 pm. All was ominously quiet, save the rhythmic “sneezing” chugs of the gunboat steam engines.

Rear Admiral Hope was aboard Plover, leading his Lilliputian fleet as if he were Nelson at Trafalgar. He was dressed in full uniform, his epaulettes and gold buttons flashing in the torrid summer sun. Hope positioned himself on Plover’s cookhouse, a proper vantage point to observe the coming action.

Silence, And Then All Hell Broke Loose

Things were still deceptively quiet. The first boat broke through the first boom, but the Chinese guns were still silent. Then, just as the leading gunboat reached the second boom, all hell broke loose—the Chinese forts opened fire almost simultaneously. Within seconds the gunboats were experiencing the concentrated crossfire of 40 Chinese guns, with calibers ranging up to eight inches.

Salvo after salvo pumped a steady hail of roundshot into the struggling British vessels. Cannon discharged with a thunderous roar, and the normally placid waters of the Hai boiled as the shot fell thick and heavy. White geysers erupted, marking near misses, but the volume of fire was such that many hit their targets.

Plover became a charnel house, its decks strewn with the bloodied corpses of British bluejackets. Admiral Hope’s tiny cookhouse “quarterdeck” also came under heavy fire, the admiral himself sustaining a painful wound in “the fleshy part of his thigh” from a glancing Chinese cannonball. He was lucky; a lieutenant aboard Plover had been cut in half by a speeding projectile. Hope soon had his wound dressed, insisting Plover continue the fight—but there were few able-bodied sailors to carry out his orders.

British Suffer Horrible Losses On The River

Nine of Plover’s crew had been killed outright, and 22 wounded. Only nine bluejackets remained, forcing Hope to transfer his flag to Opossum. But Opossum offered scant refuge, because it too was absorbing a terrific amount of punishment from Chinese guns. The admiral propped himself up by using Opossum’s mainstay as a brace, but that support was suddenly shattered by a roundshot. Hope was slammed to the deck with such force his ribs were fractured. Bleeding and in great pain, Hope was forced to relinquish command to Royal Navy Captain Shadwell.

The attack was a bloody shambles, and it was clear that retreat was the only alternative to complete annihilation. Lee had grounded, and Kestrel had sunk halfway to its funnels in the Hai’s brown waters. Cormorant was a loss, and the shattered Plover was grounded and abandoned. The Kestrel was later recovered, but the other three were written off as total losses. The human cost was even greater: Some 25 percent of Royal Navy personnel were casualties.

Americans Offer Tepid Support To British Cousins

The Americans also were present off Dagu, officially neutral but observing the fighting with growing concern. Watching the debacle, U.S. Navy Commodore Josiah Tatnall was heard to exclaim, “Blood is thicker than water! I’ll be damned if I’ll stand by and see white men butchered!” Tatnall came to the rescue, though accounts differ slightly about the extent of the American participation. The commodore sent a gig to evacuate British wounded, and some American sailors impulsively helped their Royal Navy “cousins” serve a pivot gun.

Still hoping to salvage something from the fiasco, Captain Shadwell decided on a land assault against the Great South Fort. The landing party consisted of around six hundred Royal Marines and 60 French sailors, who were accompanied by engineers and sappers with scaling ladders. The tide had fallen, the receding waters exposing a mud bank some five hundred yards wide that protected Great South Fort like a glutinous moat. The Chinese garrison opened up with everything it had, spraying the Allies with grapeshot, roundshot, matchlock musket fire, rockets, and even arrows.

A series of ditches fronted the fort, each difficult to cross under fire. Attackers found their cartridges so wet their rifles could not be fired, and wounded marines risked drowning in brackish pools or smothering in the soft mud. Accounts vary, but about 50 managed to reach the last ditch, only to huddle in the shadow of South Fort’s towering ramparts.

Chinese Repel The Attack With Withering Fire

One scaling ladder managed to reach the walls, but the men who climbed its rungs with almost suicidal bravery were forced back by a withering musket volley. No more ladders could be brought forward under such heavy fire, and it was plain the attack was a total failure. The survivors were evacuated. Accounts differ on the number of British losses, but some 89 were killed and 434 wounded in the failed land attack.

When news of the disaster reached England it caused a predictable uproar. On the whole, politicians were cautious. Lord Elgin was loath to criticize his brother, but maintained Admiral Hope “acted like a madman.” Soon, however, the voices of reason were drowned out by the swelling chorus of outraged patriotism.

Still hoping for a peaceful solution, the British Government sent instructions to Bruce that he should send the Chinese an ultimatum: Beijing had 30 days to apologize for the Dagu Forts battle, pay an indemnity, and then belatedly ratify the Tianjin Treaty. If the Chinese refused, a military expedition would be sent to force compliance. The British Government was reacting in part to public opinion, but once it became known Emperor Napoleon III was sending troops to “avenge French honor,” British participation was all but a certainty.

An Avenging Expeditionary Force Made Up of British, Indians & French

The British Expeditionary Force would consist of some 13,000 British and Indian troops under the command of Lt. Gen. James Hope Grant. Grant was a hard-working, genial Scot, competent and popular with his men. Grant’s command was made up of some of the finest regiments in the British Army, including the 44th Foot, 67th Foot, 99th Foot, and elements of the 1st Foot, 3rd Foot, and the 60th Rifles. The Royal Artillery and the Royal Engineers provided support as did the Royal Marine Light Infantry. Indian sepoys of the Punjabi Native Infantry were also included on the expedition.

Cavalry support would be provided by the First King’s Dragoon Guards and two regiments of “irregular” Indian horsemen, about eight hundred troopers in all. The Dragoons were one of the most distinguished regiments in the British army, and the Indians impressed observers with their displays of superb horsemanship.

The French expedition consisted of some 7,500 men under General Charles Guillaume Cousine Montauban. Montauban was touchy and arrogant, a strutting peacock of a man always “preening” and ready to take offense for imagined insults. The French had 30 guns, but almost no cavalry, a serious omission.

British Impulsiveness Matched By Emperor’s Immaturity

The British ultimatum was flatly rejected by the Chinese Government. In fact, the defeat of the Anglo-French forces at Dagu had strengthened the forces of reaction and hidebound conservatism. In theory the Emperor was Huangdi, the “dread lord” who was master of all he surveyed. In 1860 the Dragon Throne was occupied by a man much more immature than his 29 years would seem to indicate. Xian Feng’s routine was rigidly proscribed, isolating him from the real world. Surrounded by almost unimaginable opulence, his every whim and desire instantly gratified by a horde of fawning eunuchs and court officials—how could the Emperor achieve maturity and independent thought under such circumstances?

Because the Chinese refused to consider the ultimatum, the Anglo-French expeditions set off for China. Since a frontal assault was out of the question—no one wanted to repeat the previous year’s fiasco—it was decided the Dagu forts would be taken from the rear. The Allies would disembark at Beidang, a port about eight miles north of Dagu.

The Allied forces arrived off Beidang on July 31, 1860, but a storm of blowing sand from the distant Gobi Desert buffeted the ships and made many of the troops aboard seasick. The joint fleet stretched as far as the eye could see, 213 warships and transports whose bobbing masts seemed to spike the leaden skies above. The region between Beidang and Dagu was a flat, wind-blown expanse of mudflats, marshes, and salt-evaporation ponds. Stagnant pools held brackish water, and decaying vegetation emitted a sour stench that mixed with the salt tang of evaporation ponds and sea breezes.

Expedition Gets Literally Bogged Down In Mud

The actual landings began on August 1, with the troops still a bit queasy but none the worse for wear. The first wave was led by Brig. Gen. William Sutton, known to one and all as “Blaspheming Billy” for his sharp tongue and colorful obscenities. Eager soldiers jumped out of the boats, only to sink in the mud that at times rose to their waists. The expedition was literally bogged down in the mud—how could heavily laden soldiers negotiate these fetid bogs?

General Sutton was a man who led by example, and to everyone’s surprise he took off his boots, socks, and trousers, tying them to his scabbard and flinging the whole over his shoulder like a hobo’s pack. His men hardly knew what to make of this strange apparition, but many followed his lead and took off boots and trousers as well. An observer noted, “Picture a somewhat fierce and ugly bandy-legged little man thus accoutered in a big white helmet, clothed in a dirty jacket of red serge, below which a very short slate-colored shirt extended a few inches.” Sutton barked “come to attention and shoulder arms,” and off the redcoats went, following their barelegged brigadier.

Beidang Falls Easily

The city of Beidang was taken without resistance; most of the inhabitants had fled. The temptation to loot was just too great. French soldiers plundered with abandon, but British troops were held somewhat in check by savage discipline. Captain Con of the 3rd Foot took his duties as provost marshal very seriously indeed. Redcoats caught looting were seized and flogged on the spot. It was said that 30 British soldiers were flogged in one day.

The British set to work making Beidang a supply base for future operations, building a jetty, constructing wharves, and landing supplies and ordnance. Although British soldiers and sailors did much work, they were aided by the Chinese Coolie Corps. These were men recruited from the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, near the British colony of Hong Kong. They were organized along paramilitary lines, civilian workers who showed courage as well as a great capacity for physical labor. Unfortunately they also gained an unsavory reputation for looting and rape, and many were opium addicts.

A stone causeway was found at Beidang that led southward across the maze of mudflats and salt marshes. This causeway, about nine yards wide, was sturdy and rose well above the mire that surrounded it. It was a road—in this soggy country, almost a bridge—to Sinhe and the Hai River. From Sinhe, the causeway threaded south along the Hai to the town of Danggu before finally ending near the village of Dagu and the Dagu forts. The causeway was an obvious path to the rear of the forts—perhaps too obvious.

British Decide On Two-Prong Offensive

A reconnaissance discovered that the Chinese had thrown up a series of small redoubts across the causeway, blocking the route south. General Grant didn’t like the idea of a frontal assault down the causeway, especially since his command would be strung out and vulnerable to flank attacks. There were swarms of Chinese cavalry in the area, which the British tended to call “Tartars.” In all probability they were Bannermen, elite horsemen who were at least in part Manchu, not Tartar or Chinese. Their swift, tough ponies seemed to have little difficulty over the marshy salt flats.

Another reconnaisance on August 9 found a cart track that veered off to the right. It was muddy, and was bound to be hard going, but firmer than the surrounding ground. General Grant decided on a two-pronged offensive. The British 1st Division under Maj. Gen. Sir John Michel was to proceed down the causeway, the French in support. While the Chinese focused on Michel, Maj. Gen. Sir Robert Napier’s 2nd Division was to take the recently discovered cart track and turn the Chinese left. The Chinese were well entrenched on the causeway, but if Napier turned their flank the redoubts would be rendered untenable.

Mud, Mud And More Mud

Sunday, August 12 was the date set for the offensive, the troops welcoming a chance to quit muddy Beidang and its “detestable odors.” The 2nd Division predictably found the cart track very slow going. Mud was everywhere, a viscous, clinging muck that made every step agony. Bewhiskered Punjab Native Infantry found their mud-caked boots such an encumbrance they discarded them and trudged on barefoot.

The cavalry was also having a hard time of it; an eyewitness recalled some mounts “sank up to their girths in morasses.” The cart track was an even worse nightmare for the artillery and ammunition wagons. Urged on by whip-cracking drivers, horse teams flailed helplessly in the mire. Sweat-drenched Royal Artillery gunners, their once immaculate blue uniforms daubed in mud, put their shoulders to the wheels to lend a hand, but despite such Herculean efforts progress was slow.

Eventually the track became firmer, but it had taken Napier’s Division two hours to travel two miles. It was fortunate that the ground was now more favorable, because Chinese cavalry could be seen in the distance. The Allied advance would not go unopposed.

Chinese Cavalry Attacks

The action opened as lines of Chinese/Manchu cavalry went toward Napier’s Division at the trot. The British artillery opened fire, the skirmish marking the debut of the Armstrong breechloading gun. Shells tore into advancing lines of horsemen, the explosions ripping through horseflesh and tumbling men and mounts into the mud in bloodied heaps. Yet the Chinese cavalry was moving so fast that many shells could not find their targets.

It was up to Napier’s cavalry to deal with the Chinese horsemen. Probyn’s Horse, later the 11th Lancers, and Fane’s Horse, later the 19th Lancers, couched their weapons under their arms and moved forward. The 1st King’s Dragoon Guards also participated in the advance, their brass helmets covered in cloth against the burning rays of the sun. Fighting was hand to hand, but the Chinese were soon in full flight.

The Dragoons went in hot pursuit, but their big Irish mounts had not fully recovered from the long sea voyage and the Bannermen escaped. Still, numbers of Chinese cavalry had been cut down, the dragoons recalling how many enemy horsemen they had “bagged” as if the action had been a fox hunt.

Towns Of Sinhe And Danggu Fall To Allies

Meanwhile, Michel’s 1st Division was subjecting the Chinese along the causeway to a 25-minute bombardment. The Chinese troops manning the mud fortifications replied to this fury by discharging matchlocks and breechloading jingals, but they were badly outclassed. The causeway ramparts crumbled, and the Chinese fled, leaving “dead and dying horses and men.”

Still, the Chinese, Mongol, and Manchu troops had shown great courage. General Napier recalled, “They bore unflinchingly for a considerable time, such fire as would have tried any troops in the world.”

The Allies moved on to the village of Sinhe, a paradise compared to the filthy wretchedness of Beidang. The gardens of fresh vegetables, not to mention orchards of peach, apricot, and pear trees, made Sinhe an oasis of plenty in a sea of mud. Danggu was soon taken, a small town that hugged the Hai River, and with its fall the nearest Dagu fort was only three miles away.

Plan Needed To Take Dagu Forts

The capture of the Dagu forts was a key objective of the campaign, but how to accomplish this end? During planning sessions the Allied commanders had a serious difference of opinion. General Montauban proposed a plan that was thoroughly conventional in approach. The Allied army would cross the Hai River and march along the left bank, taking the southern forts as they did so. Once the southern forts fell, the northern fort garrisons’ avenue of escape would be blocked, compelling them to surrender. Lieutenant Colonel Wolseley remarked that the French plan had great weight—but only if “we had an army of 100,000 men.” The Allies had only about 19,000 effectives.

Crossing the Hai would be a risky proposal. The relatively small Allied army would be splitting its force in the face of a superior enemy, since some troops would have to remain north of the river. Also, the fragile Allied line of communication and supply from Beidang would grow even longer—and have to cross the river to boot. Prince Sange Lin was the commanding general of all Chinese forces in the area, a man not without military talent and strategic sense. Suppose his highly mobile cavalry cut the Allied supply line and trapped the Anglo-French Army south of the Hai River?

Competing British And French Plans

There were four major forts guarding the mouth of the Hai, two on the northern bank and two on the southern. The two largest forts dominated the entrance, and were sometimes called Great North Fort and Great South Fort. The Great South Fort had been the scene of the British debacle the year before. Second Division commander General Charles Napier was an engineering officer with a keen eye for topological detail. Napier decided—Grant concurring—that the Small North Fort was the key to the entire area.

Intent on blocking enemy warships from entering the river, the Chinese had sited Small North Fort in such a way that it dominated the others. Once taken, its guns would compel the other four forts to surrender. Under the Grant/Napier plan, the Hai would guard the Allied right flank as it advanced on the Dagu forts. Under the French proposal, the river would be more foe than friend, a watery barrier between them and their Beidang supply base.

The French reluctantly agreed to the British plan, and preparations were made for an assault on Small North Fort. Small North Fort was indeed smaller than its nearby “brothers,” but still formidable in its own right. The post was a compact structure measuring some 130 square feet in diameter. Its walls were of mud, although some accounts insist there was also unburned brick. Small North Fort also had a cavalier, or raised, platform, a man-made “mountain” that hovered over the battlements and allowed the Chinese to fire in all directions.

Collision Of Artillery

The 30-foot-high parapets were crenellated, the row of embrasures looking like a line of jagged teeth. Guns in each embrasure, some 47 in all, poked out like stubby black fingers. The Chinese had a wide variety of ordnance, including two English 32-pounders, naval guns taken from gunboats sunk the year before.

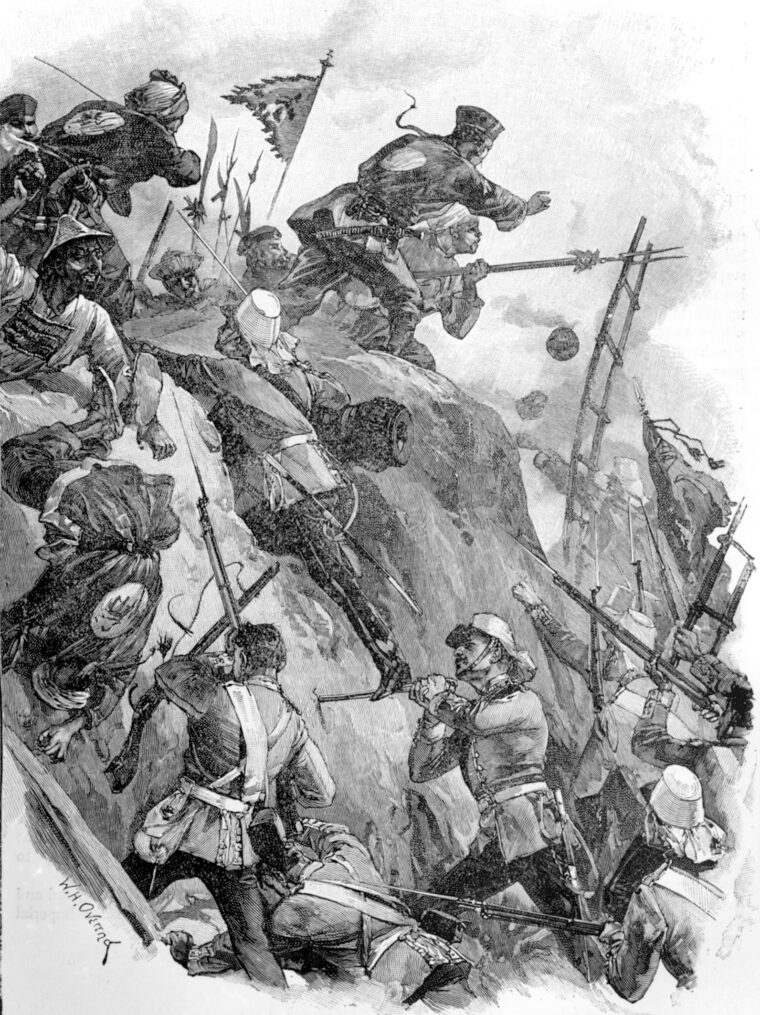

The attack began at about 5 am on August 21 with an Allied artillery barrage. The Royal Artillery and engineers had achieved wonders, literally manhandling 16 heavy guns to within a few hundred yards of the fort. Besides the Armstrongs, they had brought up British 8-inch howitzers designed to lob shells over any barrier. It was just becoming light when the Allied artillery opened fire, shattering the morning stillness with such a roar that startled waterfowl shot up into the sky in a panicked rush of wings.

The Chinese replied to this fury with a cannonade of their own, starting an artillery duel that lasted the better part of an hour. Howitzer shells arced up in a graceful but deadly parabola before descending into Small North Fort’s interior core. The cannonade grew in intensity, and by 6 am the almost simultaneous reports from so many guns merged into one ear-numbing cacophony.

Fort Reels From Magazine Explosion

At about 6:15 an 8-inch British shell pierced the top of a fort magazine and ignited its contents. The flame-tinged explosion shook the ground and flung bits of wood, mud, and other debris high into the air. A black coil of smoke rose up from Small North Fort, and for a minute or two guns from both sides lapsed into a shocked silence. After such a literally shattering experience the Allies expected the garrison to surrender.

The interior of the fort was a shambles, and one of the Mandarin commanders was dead, but the Chinese chose to fight on. The garrison opened fire, prompting a similar response from the Allies. Shot pummeled the walls, eventually poking several breaches in its mud surface. By about 7 am virtually all the Chinese artillery at Small North Fort was out of action, the gun carriages smashed, and the crews dead or wounded. It was time for the Allied storming party to go forward.

The British storming party was composed of 2,500 men under Brig. Gen. Reeves. The bulk of the fighting would be done by elements of the 44th Regiment of Foot (East Essex) under Lt. Colonel P.W. MacManhon, and the 67th Regiment of Foot (South Hampshire) under Lt. Colonel Thomas. Other British units, including the 60th Rifles, would provide support. The French assault force was composed of about a thousand men under the command of General Collineau.

Storming The Small Fort A Perilous Proposition

Although most, and possibly all, of its guns were out of action, Small North Fort was still a risky proposition for any attacker. Two water-filled moats 45 feet wide and 15 feet deep—described by the British as “wet ditches”—ringed the fort. Between these waterways the ground was studded with a prickly “forest” of sharpened bamboo stakes. A narrow causeway led to the fort’s rear gate, but the Chinese had taken every precaution to make the Allied advance as difficult as possible.

A bridge normally spanned the first wet ditch along the causeway road, a drawbridge the second moat. The Chinese dismantled the first moat bridge, leaving a yawning chasm, and raised the drawbridge over the second. The fort gate itself was closed and reinforced with mud and upright posts.

Great hopes were placed in a pontoon bridge that the Royal Engineers had constructed to cross the wet ditches. A party of Royal Engineers and marines was assigned to bring the pontoon bridge forward at the appropriate time. Looking back a year or so after the battle, Lt. Col. Garnet Wolesley, of the 90th Light Infantry and Quartermaster General for the expedition, believed the pontoon bridge had been a mistake, and that a “number of ladders” or “a small plank bridge” on wheels would have been the better option.

Pontoon Bridge A Mistake In Retrospect

One may well imagine the thoughts that must have been going through the minds of the storming party as it waited for the signal to proceed. The memory of the bloody repulse at Dagu the year previous was not a scar, but an open wound. Veterans of the Crimea were heard to say they would rather fight the Battle of Balaklava three times over than have another go at the Dagu forts.

The storming party was finally given the order to advance, and they soon discovered the pontoon bridge was more hindrance than help. It was heavy and cumbersome to carry under combat conditions, and moving it forward was proving a nightmare. When a carrier fell dead or wounded the pontoon was forced to stop until a replacement came forward. These delays were not only time-consuming, they were deadly, exposing the men to heavy fire from the fort.

Finally a Chinese roundshot—possibly support fire from Small South Fort across the river—tore into the pontoon and smashed it beyond repair. There was nothing left for the infantry to do but cross the two wet ditches as best they could. Those that took the straightforward approach and plunged into the brownish waters found themselves submerged to their armpits.

Muddy Ditch Needed To Be Crossed

Where at the first moat had been the bridge, all was dismantled save for one single beam. British soldiers tried their luck “tightroping” across it with all the intensity of circus performers. The beam was not only narrow, it was unstable, shaking with each tentative footfall. These “aerial acts” were done under heavy Chinese fire, which made the crossings all the more dangerous.

Some maintained their balance and got across, while others slipped and fell headlong into the wet ditch. They rose muddy, waterlogged, and sputtering, providing a moment of humor in an otherwise grim situation. Other soldiers didn’t risk the beam, but half-waded, half-swam the turgid moat to gain the other side.

French Have Much Easier Time Courtesy Of The Coolie Corps

The French had the luck to be supported by the Chinese Coolie Corps. Whatever their depredations behind the lines, the CCC displayed incredible courage under fire. The Coolies waded into the ditch up to their armpits, positioning themselves in a straight line in the water. They then positioned ladders lengthwise on their shoulders, thus forming a living bridge with their bodies as supports and the ladders as the road bed. Once this bridge was in place, the French experienced little difficulty in getting across. Meanwhile the first British soldiers had cleared the second wet ditch. Colonel Mann of the Royal Engineers and a Major Anson quickly made their way to the raised drawbridge. Both men began hacking furiously with their swords at the drawbridge ropes that held it upright. The ropes parted strand by strand, and a few more hasty strokes finally severed them. The drawbridge crashed to the ground, forming a span across the second wet ditch, but it was so riddled with shot it looked unusable.

As time passed, sufficient numbers of British and French soldiers had reached the base of the walls to attempt an escalade. The Chinese garrison was armed with an array of crossbows, matchlocks, jingals, and even spears, weapons that were anachronistic but deadly. Missile fire from the walls intensified, a steady rain of crossbow bolts, arrows, lead shot, and even stones. Although their artillery was disabled, the garrison hurled cannonballs from the parapets by hand.

Scaling Walls An Equally Vexing Challenge

Chinese soldiers jumped atop parapets to get a better aim at their attackers, retreating momentarily only to reload their matchlocks. The French managed to get three or four ladders against the walls, but when they attempted to climb up, the Chinese defenders flung them down, men and all. The French persevered, and one soldier managed to climb on top of the parapets with his country’s tricolor flag. The sight of the tricolor waving above the fort raised a cheer, but the triumph was fleeting. The soldier was shot through the heart, tumbling headlong from his hard-won perch.

The British pressed forward, and Ensign Chaplin of the 67th planted the Queen’s Colour on top of the fort’s battlements. This was uncommon bravery, but also an uncommon risk. The Queen’s Colour was the very essence of a regiment, its symbolic heart. Its loss or capture was the ultimate disgrace, and by having its flag in the forefront of the battle the 67th was taking a dire chance.

British Breech The Wall

In the meantime British troops had reached the fort’s rear gate. Repeated attempts to gain entrance proved fruitless, so the hard-pressed soldiers improvised. Lieutenant Kempson of the 67th shoved his sword into the fort’s mud wall, making a foothold for Lieutenant Robert Montresor Rogers to reach an embrasure to the right of the gate. Lieutenant Rogers, though badly wounded, was said to be the first British soldier inside the Dagu fort.

Others followed, and simultaneously the French broke in on the other side. The Chinese garrison resisted to the last, and fighting was hand to hand. There had been two high-ranking Mandarins in the Small North Fort at the time of the attack, and one had been killed when the magazine exploded. The remaining Mandarin fought on, inspiring the garrison with his example. Refusing to surrender, he was dispatched with a pistol shot from Captain Prynne of the Royal Marines, who appropriated his ruby-buttoned cap with its distinctive peacock feather plume as a souvenir of the encounter.

Once they were inside the fort, British and French bayonets made short work of their opponents. A portion of the garrison did escape, but with difficulty, because they had to negotiate—though in reverse—the same terrible set of obstacles.

Taking The Forts Becomes A Key Victory In The Long War

Casualty figures are disputed. Some authorities reckon Chinese losses at about 1,500. The 44th Foot, one of the heaviest engaged units, lost 14 killed and 48 wounded. Another account places total British casualties at 17 dead, 184 wounded; the French 17 dead and 141 wounded. Six Victoria Crosses were awarded for the action at Dagu, one of the coveted medals going to Lieutenant Rogers.

With the fall of Small North Fort the other forts became untenable and surrendered. In one fort alone over a thousand Chinese prisoners were taken, all of whom expected to be put to the sword. The Allies simply let them go, to their surprise and relief.

Once the forts were secure the Allies moved on to Tianjin, just 60 miles from Beijing. Colonel Wolesley wrote his mother, “The Third China War is over.” It was not; months more of campaigning remained, culminating with the entry of the Allies into Beijing itself. But the Dagu forts had been a major obstacle, and though many battles lay ahead, none would be as tough as against these guardians of the Celestial Kingdom.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments