by Joseph M. Horodyski

On the bitterly cold, windswept morning of February 18, 1944, the crews of 19 De Havilland Mosquito Mk.VI fighter-bombers took off from an English airfield. Their mission was World War II’s most daring low-level precision bombing raid to date. They were sent not to destroy the enemy, but to save the lives of scores of French Resistance fighters scheduled for execution by the Gestapo.

In the days before smart weapons and laser-guided bombs, they were to fly in at virtually treetop level and in a matter of minutes attempt to free their allies from a prison fortress. The slightest hesitation or miscalculation could turn their rescue mission into a tragedy. The young pilots who volunteered for this mission were the best Britain had to offer. Highly trained and motivated, their flight would rely on equal parts of skill, daring, and the right amount of luck.

Resistance Steps Up Activity Ahead Of D-Day

The story begins in early 1944, when French Resistance members sent word to Britain that approximately 700 prisoners were being held by the Gestapo at Amiens prison, near Abbeville. These captives included a mix of political prisoners and resistance fighters who had been convicted of crimes against the German occupation forces in northern France. A large number of them were resistance network leaders who had been sentenced to death in late February as an example to the civilian population.

An increasing number of sabotage and assassination missions were being conducted against the occupying Germans. These missions, aided by British supplies and experts who had either been flown in or parachuted in under cover of night, had grown in intensity in the months leading up to the planned Normandy invasion. One of the prisoners scheduled for execution was Louis Vivant, a key resistance leader who had been captured by the Germans in 1943. Now the resistance once again appealed to the Royal Air Force, not for supplies or weapons, but for British help in initiating a breakout of the prisoners, even if at the expense of some of their lives. It was clear that the longer these prisoners remained in German hands, the greater the chances that they would reveal vital information during torture and interrogation.

Developing a Highly-Detailed Model of Their Objective

Britain’s liaison with the resistance, the SOE (Special Operations Executive), passed the request on to the Air Ministry, which then assigned it to the RAF mission planners, and intelligence experts studied the situation and in less than two weeks devised a plan that might accomplish the impossible. French Resistance members provided the British with many details on the layout of the jail and its daily routines.

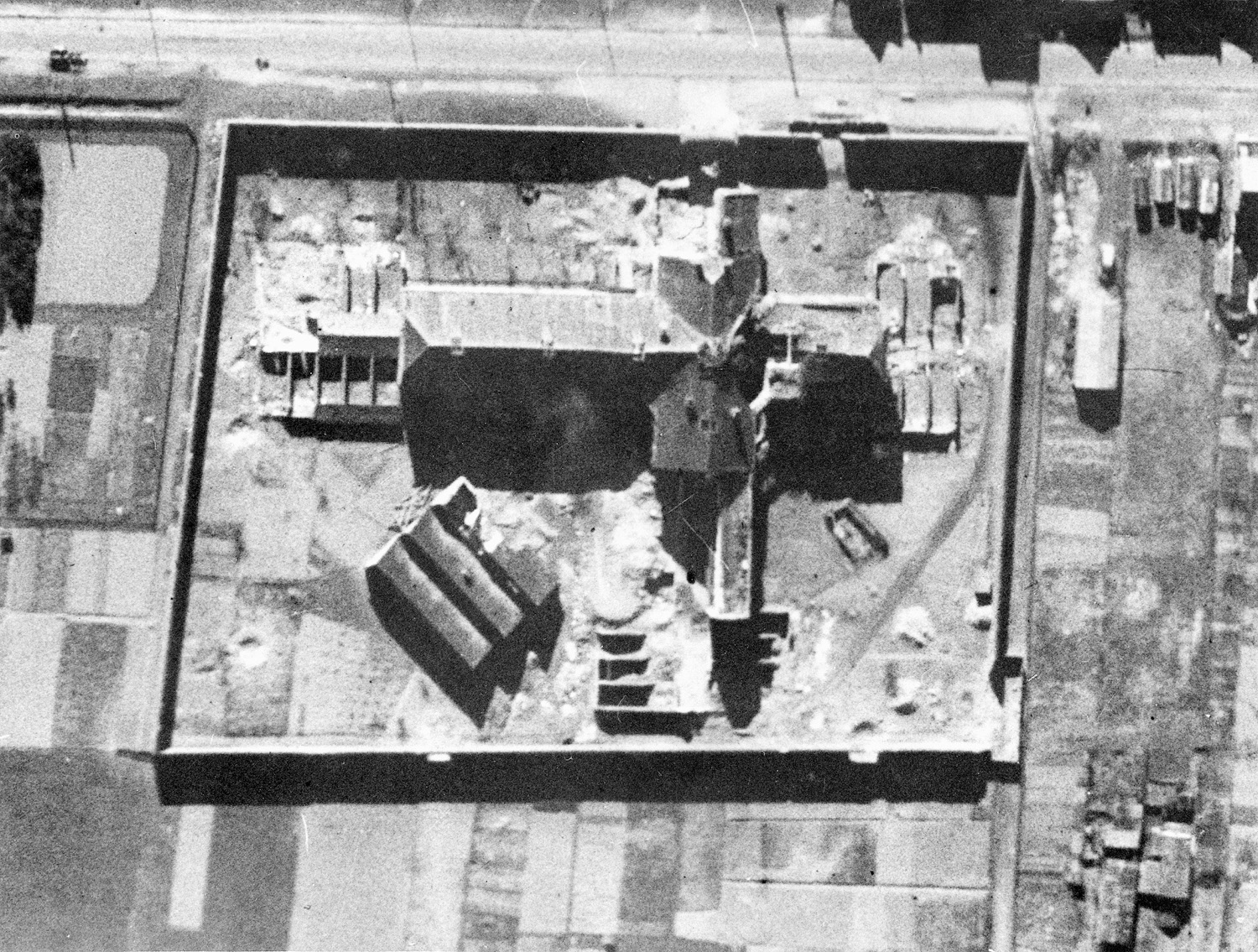

Photographs from various reconnaissance missions were pieced together to enable planners to construct an accurate wooden mock-up of the prison compound to enable pilots to familiarize themselves with the layout. This model also allowed the planners to study the prison from any angle, simulate different kinds of weather and lighting conditions, and examine the options that held the greatest chance of success with the minimum risk to life. The model for this mission was actually much larger than usual, so the attacking pilots could study it from different vantage points. All the details needed to be committed to memory, and all movements made by intuitive reflex action. Indeed, the attacking aircraft would be coming in so low that some aircraft actually had to climb to clear the 20-foot courtyard walls.

Operation “Jericho” Would Make the Walls Tumble Down

It soon became apparent that three objectives would have to be met almost simultaneously for the mission to be carried out. First, the cell walls of the prison building would have to be destroyed without killing, if possible, any of the prisoners held within. Second, a breach would have to be made in the perimeter walls of the courtyard through which as many prisoners as possible could escape in the chaos of the attack. Third, enemy defensive fire had to be suppressed to allow the Mosquitos to get in as close as possible to do their jobs and escape before any of the German fighters stationed nearby had a chance to respond.

Precise navigation was also essential to the attackers’ ability to avoid nearby German airfields and antiaircraft guns. An added element of danger was the need to avoid hitting any overhead power cables or telephone lines that might be in the area, which would have meant instant death to the crew involved. The operation was given the codename of “Jericho,” after the biblical story of the fabled city of Jericho whose walls were destroyed by Joshua.

Eighteen Mosquito fighter-bombers, six from the 487th Royal New Zealand Air Force and six each from the Royal Australian Air Force’s 464th and 21st Squadrons, were chosen for the operation. They were armed with two 500-pound bombs, each with 11-second delayed detonators. The bombs were to breach the three-foot-thick prison walls and, precisely three minutes later, smash the inner buildings. The attack force would be escorted by 12 Typhoon fighters as protection, while a 19th Mosquito from the RAAF film production unit recorded the operation for future damage assessment.

Delayed No Longer

Speed was essential, as it was known that the Gestapo would in all likelihood advance the date of the executions if word of the surprise raid leaked out. The operation had originally been planned for January, but poor weather conditions forced repeated postponements, to the frustration and dismay of all involved. Word was then received in mid-February that 20 resistance members were scheduled to be executed sometime within the next two weeks.

No more delays could be chanced, so the operation was reset for February 18, regardless of conditions. On the planned date the weather was appalling. Heavy snow was falling on the RAF base at Hundson, Hertfordshire, 30 miles north of London, as the crews assembled for a hot cup of coffee and a final briefing. It was only at this point that the final crews for the flight were chosen by their squadron commanders. The decision was based on the crews’ performance during the previous two weeks of hectic training in low-level tactics.

After studying a model of the prison for two hours, these crews, two to an aircraft, rode out to the flight line where ground crews already had the engines of their aircraft warming up. At 1055 hours, the 487th RNAF Squadron was the first to take off, led by squadron commander Irving Stanley “Black” Smith. The other squadrons followed at three-minute intervals. The overall operation was under the command of Group Captain Percy C. Pickard and his expert navigator Bill Broadley, whose task was to lead the entire flight to their target. Pickard was a legendary figure in the RAF, a highly decorated bomber pilot who had appeared in the propaganda film Target For Tonight as a Wellington bomber pilot.

Exceptional Skill And Nerves Of Steel Required

In spite of the worsening weather, all 19 aircraft took to the air safely and on time. Quickly disappearing into the murky sky, the Mosquitos set out to rendezvous with their Typhoon escort over Littlehampton and then fly on to France, barely an hour away. High winds and threatening snow showers made for extremely hazardous flying conditions at low altitude, as well as making accurate navigation risky at best.

Once over the Channel, the plan called for the three attack squadrons to assemble in a staggered formation with the Typhoons flying top cover. The demanding mission called for the ultimate in precision flying and split-second timing. Swooping down from an altitude of only 500 feet to one of less than 20 feet to evade German radar while hugging the ground at over 360 miles per hour required exceptional skill and nerves of steel.

The planes of 487 Squadron would go in first, breaching the prison walls in two different locations as insurance in case the Germans were able to quickly seal off a single breach. Then 464 Squadron, flying three minutes behind, would blow off the ends of the main prison building and the cell doors, as well as the guard’s sleeping barracks, canteen, and mess hall. This portion of the attack was meant to generate confusion and to kill as many Germans as possible while they were sitting down for lunch. Meanwhile, 21 Squadron would orbit overhead at high level as a reserve, ready to attack in case a further assault was deemed necessary.

Germans Assumed Nothing Could Be Flying Under Such Horrible Conditions

Things immediately began to go wrong. Flying through thick overcast and blizzard conditions, two of 464 Squadron’s Mosquitos and two of 21 Squadron’s turned back, while one Mosquito from 487 Squadron aborted with engine failure. Only 14 Mosquitos now remained, one of which was the unarmed photographic aircraft. The planned rendezvous with the Typhoons failed to come off, as the promised escorts were delayed in takeoff due to almost zero visibility at the airfield. The Typhoons finally met up with the flight over the Channel just as they began entering enemy airspace.

After crossing the French coast, the attacking force approached the target, altering course to approach from the north and east in an effort to achieve surprise at the crucial moment. Amazingly, their presence had not yet been detected by the Germans, either by radar or visually, because it was assumed nothing would be capable of flying in these weather conditions.

After a final navigation check to ensure that they had not somehow strayed during the intense winter storm, the unseen attackers converged on the unsuspecting Germans, heading precisely toward their target. At 1203 hours, just as the garrison began sitting down for their midday meal, three Mosquitos of 487 Squadron swept in out of the gray skies. To the complete surprise of the Germans, they dropped 12 bombs precisely on the eastern wall of the Amiens prison complex.

Mosquitos Catch Germans By Complete Surprise

The lead bomb was seen to hit the wall about five feet above the ground, while other bursts were seen to go off adjacent to the west wall and a few overshoots exploded in the fields to the north. Two more Mosquitos attacked the north wall at precisely the same instant, just barely clearing the masonry. These aircraft then began taking out buildings in the inner courtyard as alarms sounded and dozens of startled German troops began pouring into the open to see what was happening. Those that did were cut down almost instantly, staining the freshly fallen snow with their blood.

Three minutes later, at 1206, the second wave approached just below the overcast and went in as 464 Squadron took its turn and tore a 12-foot breach in the eastern wall, skimming the target at a height of only 20 feet. Eight 500-pound bombs took down a center section of the wall, while two more Mosquitos bombed the main prison buildings from a height of only 50 feet, scoring eight more direct hits and blowing open the jailblock in the process.

It was amazing that no midair collisions occurred. The attacking aircraft somehow managed to avoid hitting each other while converging from three different directions at top speed. One Mosquito from this second wave was hit as German troops, recovering from their initial shock, began returning fire. This aircraft flew off to the west trailing smoke.

Imprisoned Resistance Fighters Escape Amid Confusion

Smoke billowed from a dozen places as stunned, dazed prisoners started to react. The mess hall, canteen, and sleeping barracks were the last to be hit, and scores of German troops were killed before they even had a chance to react. Low-flying Mosquitos began strafing the barracks buildings in an attempt to aid the escape of as many prisoners as possible. Ground fire was sporadic and confused as most guards dove for cover rather than attempting to stop the prisoners’ escaping.

The lone Mosquito from the photographic unit circled the burning courtyard three times between 1203 and 1210 at a height of 400 feet, recording the scene for analysis by intelligence experts. Flight Lieutenant Tony Wickham and his cameraman Pilot Officer Lee Howard reported a large breach in the eastern center of the north wall and considerable damage to the western ends of the main buildings that housed the prison workshops. Prisoners could be seen making their escapes through gaping holes in the walls across snow-covered fields to be spirited away by the waiting resistance members who had requested the airstrike.

The four approaching aircraft of 21 Squadron, while still four miles from the target, received a radio call from Group Captain Pickard instructing them not to bomb their targets as considerable damage had already been inflicted on the buildings, and prisoners were seen swarming all over the target in an attempt to escape. Pickard’s machine was the last over the prison, just seconds before the delayed-action bombs began exploding. These last four Mosquitos from 21 Squadron circled the target for a final time, confirming that the pall of smoke was too heavy to permit further accurate bombing, then set course for home. The prearranged success signal, “Hello Daddy, RED-RED-RED,” was then transmitted to anxious planners waiting back in London.

Fighting Their Way Back Home

Casualties were heavy inside the prison. Some of the escapees were almost immediately recaptured, and a number of civilians outside the prison complex were killed. Two Mosquitos went missing. Just as the attackers began their withdrawal, a flight of German Focke-Wulf 190s arrived on the scene. One spotted Pickard’s aircraft and dove on its prey.

Pickard’s aircraft was hit and plunged to the ground just outside the courtyard walls, instantly killing Pickard and Broadley. A lone Mosquito from 487 Squadron was seen attacking a gun position near Freneuville during the return flight at 1210 hours. That plane was reported hit and losing altitude toward the east. A small air battle ensued, and one of the escorting Typhoons was downed as the attack group desperately began fighting its way back toward the Channel.

Now alerted, German flak batteries all the way to the coast kept a lookout for the raiders. Flying near Albert, one Mosquito of 21 Squadron, hit by flak that holed its starboard engine nacelle and undercarriage, promptly collapsed on landing. Another aircraft from 464 Squadron was hit, wounding the pilot, Squadron Leader Andrew McRitchie, who bailed out south of Oisemont and was captured. His navigator, Flight Lieutenant R.W. Sampson, was unable to leave the burning aircraft in time and was killed on impact with the ground.

Vital Resistance Members Freed By Operation Jericho

Two more Mosquitos from 21 Squadron went down over the Channel due to engine trouble on the return flight, but both crews were rescued. One RAF Typhoon of the covering force, which arrived late to cover the withdrawal, also went missing. It was never determined if the fighter was lost due to weather, mechanical trouble, or hostile ground fire. Of the 14 Mosquitos that made it to Amiens, nine exhausted crews returned to their bases with varying degrees of damage. The final aircraft touched down at 1300 hours, after a mission lasting barely more than two hours.

The raid achieved its purpose. Of the 700 prisoners being held in Amiens cells, 102 were killed and 74 wounded during the operation, but an astonishing 258 managed to escape and avoid recapture. Half of these had been scheduled for execution the very next day. Of these, 179 were listed as common criminals, 29 were termed “French politicals” (Communist Party workers), but at least 50, including Louis Vivant, were vital members of the French Resistance, some of whom had been convicted of committing violent acts against German soldiers. These members were absorbed back into the resistance network and later played key roles in operations leading up to the D-day invasion. At least 50 Germans also lost their lives in the attack on the prison fortress.

A Grateful Nation Still Remembers

Group Captain Pickard and Flight Lieutenant Broadley are buried outside the walls of the old Amiens prison close to the site where their Mosquito crashed. Both were awarded posthumous Distinguished Service Orders and Distinguished Flying Crosses. They lie on French soil, the home of those they died trying to liberate, and their graves are cared for by local villagers who leave flowers in their memory each year on the anniversary of the raid.

Most of the others who participated in the strike are now long gone, the passage of years having taken its toll, but the memory of their actions still stands tall. When extreme courage, skill, bravery, and dedication were needed, all the men who flew on Operation Jericho answered the challenge, faced incredible odds, and gave the very best of themselves.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments