By Robert A. Lynn

In the 1780s the Founding Fathers of the United States didn’t so much revise the old Articles of Confederation as devise an entirely new government as set forth in the Constitution. Congress received taxing and other important powers, and was expanded from a single chamber into a House of Representatives elected by the people and a Senate elected by the more conservative state legislatures. A strong executive power vested in a president was also provided, as well as a Supreme Court.

Thus was born the American system of the division of powers—legislative, executive, and judicial—acting as checks and balances one on another. In Congress the people, as manifested by the popularly elected House, were balanced against property, as expressed by the Senate. Civilian control of the military was guaranteed by making the president commander-in-chief, and the president in turn was checked by giving the House the power to determine the size of the armed forces.

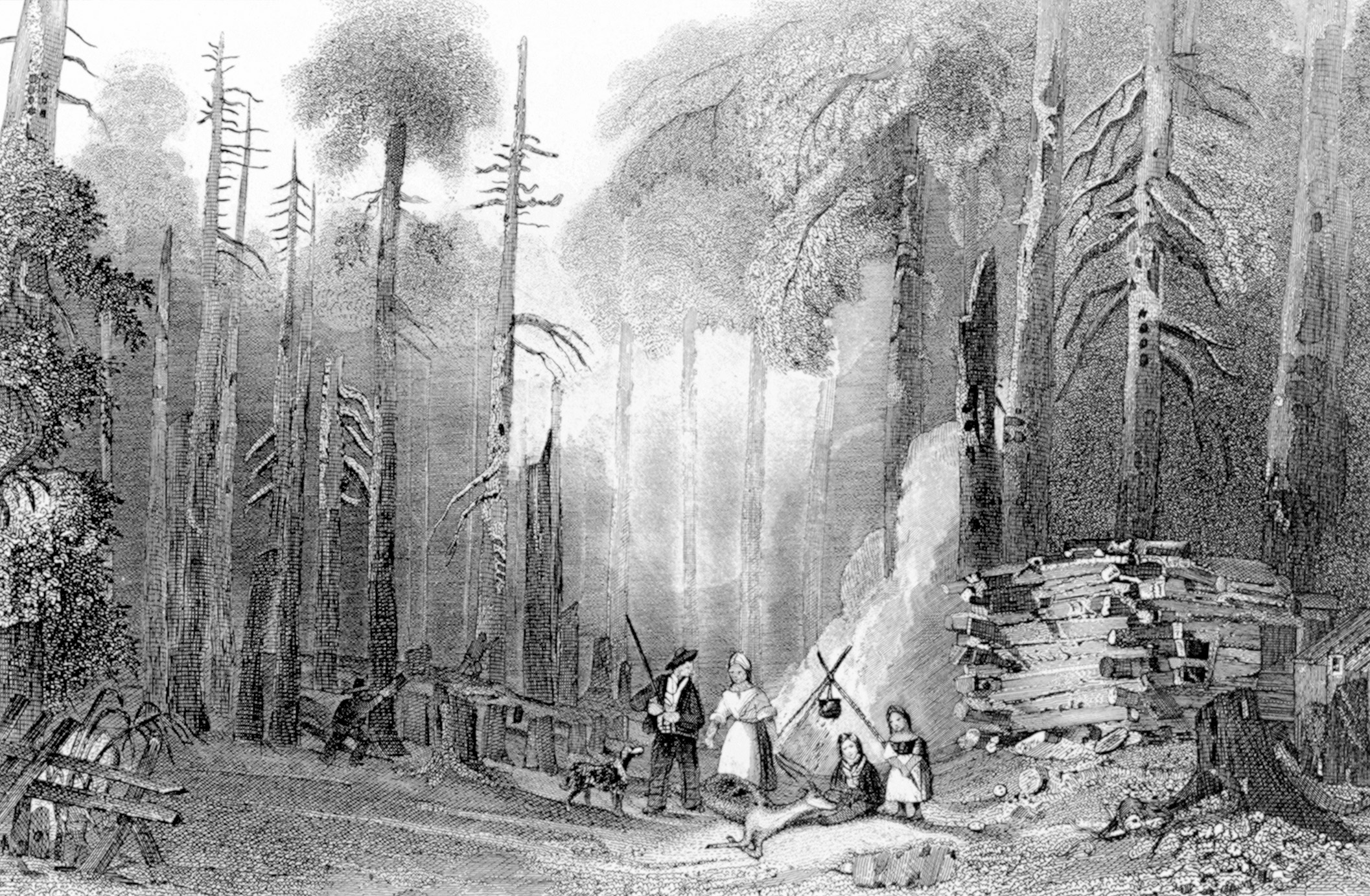

The new government began life without money or an administrative system, no Navy or Marine Corps, and an army of only 672 officers and men who were responsible for peace in the Northwest Territory, an area that comprised 248,000 square miles of prairie, forests, rivers, and mountains.

Great Britain hadn’t withdrawn from her seven Northwest posts (Pointe au Fer, Oswegatchie, Oswego, and Niagara in upper New York, and Miami, Detroit, and Michilimackinac in Michigan) as she had agreed to in 1783 and also divided Canada into the provinces of Lower and Upper Canada (modern-day Quebec and Ontario) with Upper Canada’s seat of government at Fort Niagara, which was located on the American side of the border.

Within the political spectrum in Great Britain were the Whigs, who saw the United States as an ally; the Tories, who begrudgingly treated the U.S. as an equal; and a small but vocal minority within the British Army (supported by the displaced American Tories) who firmly believed that this newly independent nation would in time fall apart, leaving them to take up where they had left off. Hence their refusal to leave the forts in New York (where the majority of American Tories came from) and Michigan, from which they could influence the Indians in the Northwest Territory. This influence would cost the British between $20,000 and $30,000 a year as well as gifts and supplies of equal value.

The majority of Americans didn’t care one way or the other about the forts because they traded with them. But Northwest Territory settlers who were trying to make a home and start a new life were outspoken about their situation. Such included not only Indians (specifically the Shawnee) raiding their homes and farms but the suspicion that the Indians were being supplied with arms and ammunition from Great Britain. They were right in that Sir Guy Carleton (Lord Dorchester), Governor of Canada, didn’t intend to lose the revenue from the fur trade of the Northwest Territory and keeping the Indians sufficiently warlike was part of his plan.

But the Territory’s pleas fell upon deaf ears because the same Americans who looked the other way in regard to the British garrisons on U.S. territory refused to believe that now, years after the end of the American Revolution, Great Britain was still encouraging such mindless and senseless butchery.

Within months of George Washington’s assuming the presidency of the United States in April 1789, attitudes toward the situation in the Northwest Territory began to change. The stories of the raids and massacres (many times inflated) committed by the Indians evoked little sympathy either in Congress or the Executive Branch. Washington never had any liking for the Indians but preferred a negotiated peace to war whenever possible.

Keeping in mind the consequences of open warfare, Washington sought congressional approval in August 1789 to send a temporary commission to make peace with the Creek and secure the southern frontier. The Creek delegation arrived in New York in 1790 willing to negotiate. President Washington received them cordially with a reception at his residence, a formal military review, and a visit to one of this country’s new frigates, the USS America. Although he and Secretary of War Knox approved the new treaty, they ordered an armed expedition against the Miami and Wabash tribes because of their repeated attacks on boats along the Ohio River and raids into Kentucky. Other members of Washington’s administration fully supported this policy (including Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson), although some acknowledged that the Indian-white enmity was fired as much by settler attacks on Indians as by Indian attacks on settlers.

Secure in the knowledge of solid support, President Washington instructed Northwest Territory Governor Arthur St. Clair to call out the militia to reinforce the small contingent of Regulars who were to have some artillery with them.

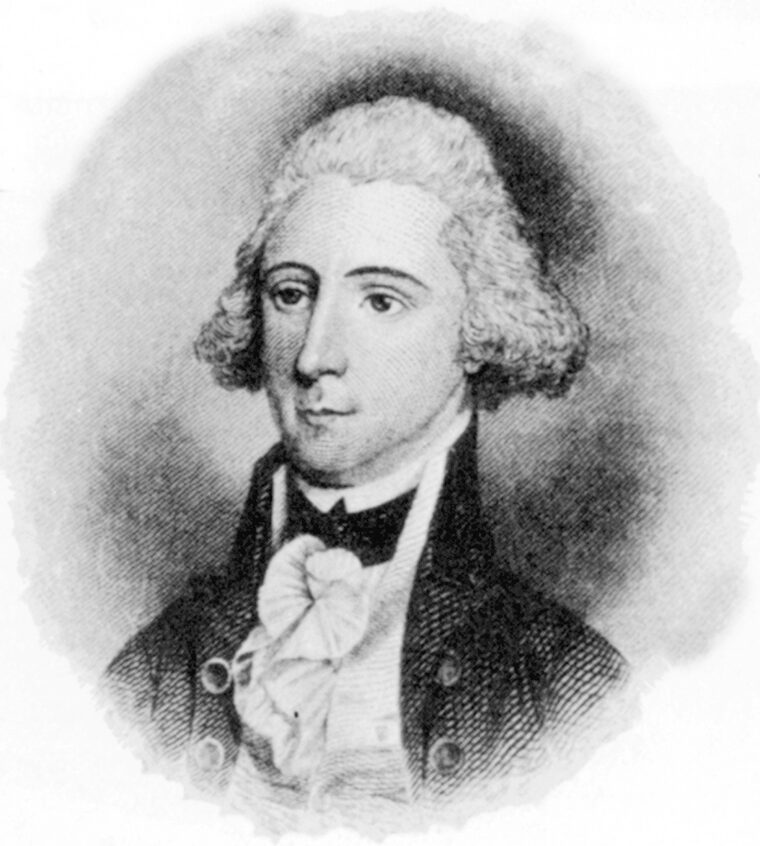

The Mediocre General

At the time of his appointment as governor in 1787, Arthur St. Clair had had a checkered and uneventful career. He was born in Scotland in 1737, attended the University of Edinburgh, inherited a large sum of money, and bought an ensign’s commission in the 60th Regiment of Foot (Royal Americans) in 1757. He was sent to the Colonies where he took part in Lord Jeffrey Amherst’s capture of Louisburg in 1759 and General James Wolfe’s capture of Quebec in 1762.

In 1762, St. Clair resigned his commission and settled in the Colonies. He courted and subsequently married a Massachusetts belle and settled on 4,000 acres in the Ligonier Valley of Pennsylvania. Upon the outbreak of the American Revolution, he sided with the colonists and was appointed to the rank of colonel in the Continental Army. He served in the Canadian Campaign, Trenton, Princeton, Fort Ticonderoga, Brandywine, and Yorktown but his military service was mediocre to say the least, even though he rose to the rank of major general.

St. Clair returned to civilian life and went into business as a director of the new Ohio Company, which, like its predecessor of 35 years earlier, was trying to colonize the land north of the Ohio River known as the Northwest Territory. He became a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1786, winning the presidency of that body shortly before the Northwest Ordinance passed. As the new governor of the Northwest Territory, he became responsible for directing any campaign that might be conducted against the rebellious Indian tribes in that area.

But once in office, St. Clair found that settlers, owing to the stories of Shawnee massacres, were scarce. Further complicating his duties was the fact that he was soon overwhelmed and shaken by the existing settlers’ letters about their suffering at the hands of the Shawnee. Between 1784 and 1790, the settlers of the territory suffered 1,500 killed by the Shawnee, a large amount of suffering for a population (in 1790) of just 4,280 whites and Negroes, including French families who had remained after 1763.

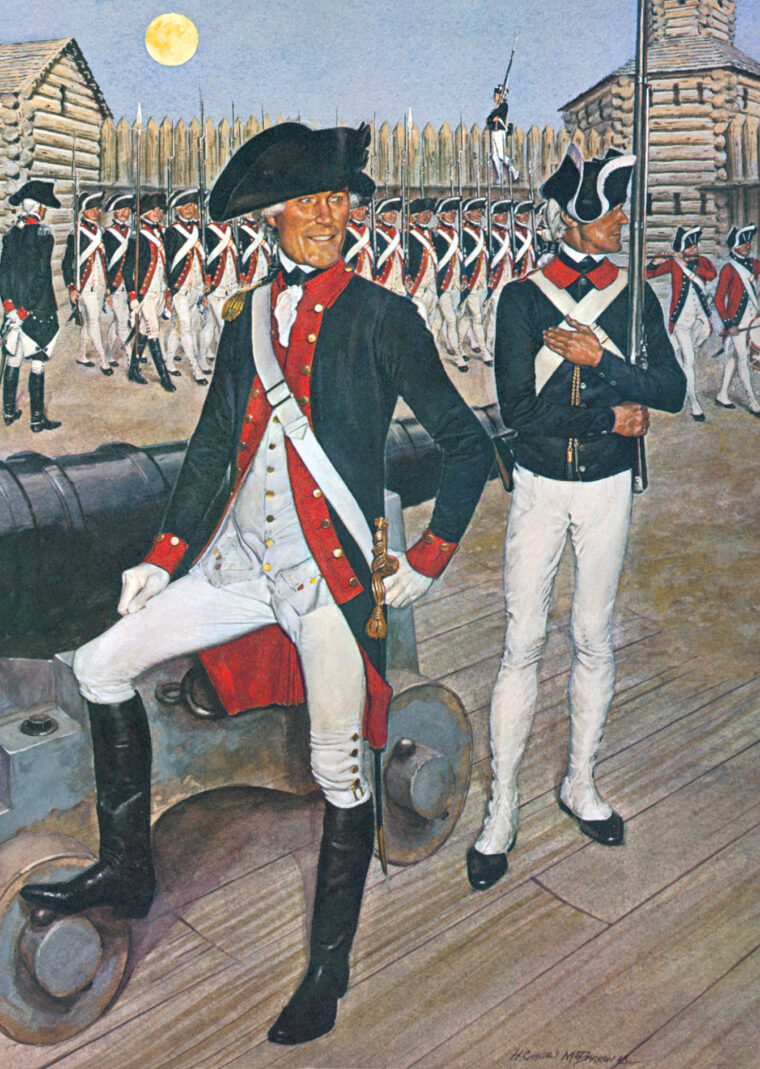

The officer chosen to lead the first expedition against the Indians was Brig. Gen. Josiah Harmar. Born and raised in Pennsylvania, Harmar was a veteran of the American Revolution during which he served with the Pennsylvania Line under General Anthony Wayne. After the war, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and put in charge of Fort McIntosh on the Ohio River. In that capacity, he was to check, even reverse, the movement of settlers into the Northwest Territory while negotiations were being conducted between the government and the Indians.

Several years of negotiations failed, either to stem the flow of immigrants or curtail Indian attacks. Knox’s increasing nervousness was highlighted in a letter to President Washington in 1789, in which he stated that “since the conclusion of the War with Great Britain, hostilities have almost constantly existed between the people of Kentucky and the Wabash Indians.” These same sentiments were expressed by Governor St. Clair in the fall of 1789. He stated that now was the time for more serious action.

Recalling that under the Second Continental Congress “the Governor of the Western Territory had power, in case of hostilities, to call upon Virginia and Pennsylvania for a number of men to act in conjunction with the Continental troops, and carry war into the Indian settlements,” St. Clair suggested that authority be renewed in order to either intimidate the Indians or to provide a force capable of effective military action. This President Washington did in 1790.

In accordance with Washington’s instructions, St. Clair named his second-in-command, Brig. Gen. Richard Butler. Butler, born in 1743 in Ireland (one of the five fighting Butler brothers), was a veteran of Pontiac’s War, Dunmore’s War, and the American Revolution. He had also been one of the three commissioners who had negotiated the Fort Stanwix and Fort McIntosh treaties, which set a boundary between U.S. and Indian lands and required the Indians to “yield to the U.S. all claims to the country west of said boundary.”

Responsible for the critical task of obtaining all necessary supplies and equipment for the expedition was Quartermaster General Samuel Hodgdon. Like St. Clair, Butler, and Harmar, Hodgdon was an experienced soldier whose previous position was as commissary of military stores in Philadelphia. His performance during the upcoming campaigns conducted by Harmar and St. Clair was critical.

On June 7, 1790, Knox ordered General Harmar to “extirpate, utterly, if possible” the banditti whose attacks were keeping that part of the frontier in constant turmoil. The authority for this action was granted during the first session of the new Congress established under the Constitution.

Also during this session, Congress gave the president broader powers by passing, on April 30, 1790, an act permitting enlistments for a three-year period of service and increasing the army to 1,216 NCOs, privates, and musicians with an appropriate number of commissioned officers. The effort was to expand the U.S. Army from the 884 officers and enlisted men reported to Congress in 1789.

St. Clair immediately called upon Virginia for a thousand militia and Pennsylvania for five hunred and placed General Harmar in charge of the upcoming campaign. Both St. Clair and Harmar planned a two-pronged offensive: Major John F. Hamtramck, a competent and well-liked officer of French-Canadian origin, would drive northeast from Vincennes, up the Wabash with his Regulars and 300 Virginia militia and attack the villages there while Harmar took 320 Regulars; 1,133 Kentucky, Virginia, and Pennsylvania militia; three artillery pieces; and a large supply train of 868 pack horses from Fort Washington (modern-day Cincinnati) and moved north.

Their joint objective was Kekionga (the site of modern-day Fort Wayne, Indiana), the principal village of the Miami tribe, where both forces would converge and lay waste villages, supplies, and fields and inflict casualties on the Indians who would be forced to fight in defense of their homes. The Indians not killed would be scattered and left destitute in the face of the approaching winter.

Harmar told his men that much was riding on the expedition: the future of the army and the future of westward expansion by the American people. Further, the men were told that the land as far west as the Mississippi River was U.S. soil and that no Indians were going to deny this land to the American people. The young and vibrant nation couldn’t let this situation continue.

But unknown to Harmar and Hamtramck, their plans would be compromised by two things: first, Alexander Hamilton’s cozy relations with a British military intelligence officer named Beckwith (President Washington was unaware of this) had alerted the British in Detroit to America’s plans; and second, St. Clair further compromised the plan by notifying Detroit in advance that Harmar’s expedition was against the Indians and not the British. This was in direct violation of President Washington’s orders of not telling the British until the expedition was so far under way that there would be no time to relay that information to their Indian allies. The Indians were warned by Detroit’s commander, Major Patrick Murray.

From the start of the campaign, U.S. forces were handicapped by corrupt contractors who only slowly delivered food, horses, guns, wagons, and ammunition. To complicate matters, the militia consisted of young boys, old men, and foreigners recently arrived in this country. The weapons that they did bring (some didn’t bring any) were badly in need of repair. They even lacked the most elementary equipment like axes and cooking utensils. In addition, forage was difficult to find for cattle, pack horses, and horses of the mounted troops. This hadn’t been anticipated because the expedition was planned as a summer maneuver. Due to these problems, the army wasn’t ready to march until September 26. It wouldn’t reach its objective until October 17, by which time the grazing areas would be covered with frost.

Harmar solved the command problem among the militia by placing Lt. Col. James Trotter in command of the three battalions from Kentucky and Lt. Col. Christopher Truby in command of the one battalion from Pennsylvania; Colonel John Hardin would coordinate all four battalions. Even though Hardin was the senior commander, the men favored Trotter, who wasn’t above encouraging dissension among the militia. So it was that General Harmar set out on this nation’s first major military operation.

Desperate Indians With a Reputation for Savagery in Battle

The Indians facing Harmar’s and Hamtraks’ soldiers had a number of advantages: They were at home in the forest, they decided where and when to fight, they could assemble and disperse more rapidly, they were fighting for their homes, and they had a reputation for savagery that gave them a psychological edge in battle. On the other hand, the Indians faced a number of disadvantages: They possessed few of the technological materials of war at the time, no command structure existed, no individual was compelled to fight, discipline was unreliable, the braves in battle fought more as individuals than as a team, and, owing to a declining population, they could only create a large force by piecing together intertribal alliances, which brought more problems. For such reasons, the Indians preferred small wars.

Even with the difficulties encountered by General Harmar in planning and organizing the expedition, he felt reasonably optimistic. This confidence was based on two things: First, the quality of his Regular troops and their leaders was solid due to years of duty on the frontier; and second, Indians had only run away from his previous expeditions. Thus, his attitude was one of cockiness rather than respect.

On September 26, Harmar sent Colonel Hardin and his militia northeast from Fort Washington, away from Kekionga. Harmar hoped this deception would mislead the Indians. Secure in this belief, Harmar marched with the rest of his army on September 30, following the trail cleared by his militia.

Meanwhile, Hamtramck was late. His column was supposed to begin its advance up the Wabash by September 25, but the Kentucky militia didn’t arrive until September 29. Even though the militia showed up under strength and unready, Hamtramck was anxious to start. This he did on September 30 with only 50 Regulars and 290 militia, leaving 90 behind who were too sick or ill-equipped to march.

Harmar was unaware of Hamtramck’s troubles and therefore pushed his units hard while still maintaining security. He kept his flanks covered and scouts well forward. Nighttime bivouacs were set up in defensive squares, with the supply train placed in the center. Even though he advanced through rainy weather Harmar did about 10 miles a day. He marched northeast until he reached modern-day Springfield (where George Rogers Clark had defeated the British and their Indian allies during the American Revolution) where he turned sharply left and pushed straight ahead to Miami Town.

On the morning of October 13, scouts ran across two Indians and were able to capture one who said that Harmar’s column had been under constant surveillance since they began their march. Harmar also learned that at Kekionga there were only a few hundred warriors, who planned to withdraw rather than fight. Harmar was upset but decided to detach a raiding party of mounted troops to catch them before they could get away. The only mounted troops he had, however, were the Kentucky militia under the command of Colonel Hardin. They were ordered to begin their advance on the morning of October 14.

But morning came and went and with it Hardin’s planned advance. His force didn’t start until late and then became lost. By nightfall, Hardin’s men were only four miles ahead of the main body.

Meanwhile Hamtramck’s column turned back to Vincennes. After advancing up the Wabash for 10 days, they came upon vacant Indian villages at the Vermilion River and destroyed them. He wished to go on to attack but he couldn’t do so and yet return to Vermilion in less than nine days, and he would have to do it at half-rations, for provisions were short: 14 days’ flour and 10 days’ beef. The majority of the militia deserted and the ones left threatened to mutiny if they went any farther because they feared an Indian ambush. He withdrew, never meeting with Harmar or the Indians he was seeking.

Hardin’s column finally reached Kekionga on October 16 and found a hastily abandoned village. The lost day had given the Indians time to evacuate down the Maumee toward Lake Erie. Harmar’s main body arrived about noon on October 17 and excitedly the militia wandered off to loot the few huts that weren’t burned. They destroyed anything left standing, much to the disgust and dismay of the Regulars.

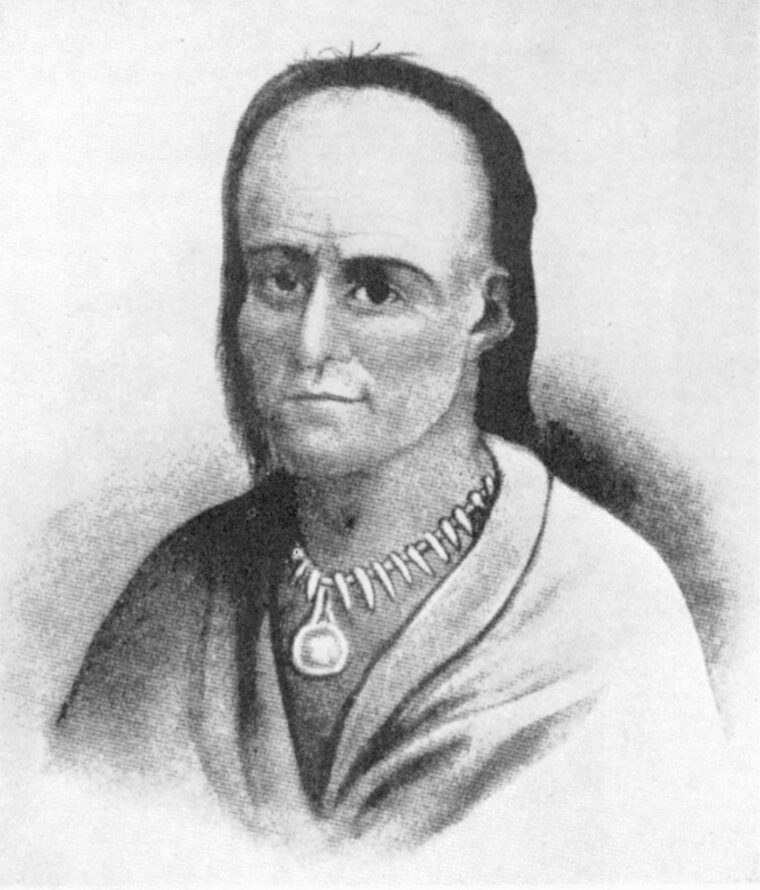

The Dignified and Respected Little Turtle

Harmar entertained ideas of continuing on to the Wabash and striking at the Wea villages, but decided against it after some Indians stole more then 50 pack horses on the night of October 17. Instead he sent a patrol of soldiers northwest of Kekionga under the command of Lt. Col. James Trotter to locate any villagers. Trotter insisted upon leading this patrol, during which they encountered two braves whom they promptly killed and scalped. The patrol returned but not before Hardin and Trotter argued again over who would command the militia. Hardin immediately approached Harmar and demanded that he be allowed to take troops out on October 19 to restore the militia’s reputation. Harmar agreed.

On October 19, Hardin left with 180 men, including 20 Regulars under Captain John Armstrong. He took the same trail as Trotter and came upon some Indians, who ran away. Hardin’s stretched-out column immediately gave chase in the direction of the Eel River village, where one of the best leaders among the many tribes resided: Little Turtle. He had set a trap and Hardin took the bait.

Little Turtle was born in 1752 to a Miami father and a Mohican mother in the Ohio country. Little Turtle, also known as Me-she-kin-no-quah, in 1791 stood six feet tall, was dignified in manner and stern of expression. He inspired respect and admiration among both Indians and settlers. Further, his intelligence and boldness, with an intuitive sense of the decisive moment in an engagement, made him a man opponents took lightly at their own peril.

Within the trap set by Little Turtle lay about 150 braves (Miami, Wabash, and Shawnee) with their war-paint patterns expertly blending into the autumn colors of the surrounding woods. Patiently, they waited for the lead militia and Regulars to fill the meadow where they had skillfully placed fur rugs, animal skins, and other gear to attract them. Once they were in the clearing, all hell broke loose.

“For God’s Sake, Retreat!”

The Indians commenced firing about 150 yards away from the soldiers and continued to advance toward them. The militia then turned toward this gunfire and were immediately blasted from behind by other Indians lying in ambush on the left. Their contempt instantly turned to fear as most of the militia threw their fully loaded muskets down and fled without firing a shot. In the ensuing panic, they pushed Colonel Hardin back with them and continued fleeing to the rear yelling to anyone who would listen: “For God’s sake retreat—you will be all killed—there is Indians enough to eat you all up.”

Captain Armstrong quickly ordered his column of 30 Regulars to form a line, hoping that the militia behind him would close up and fight. But they panicked too and quickly followed the other fleeing militia. So it was left to Armstrong and his 30 Regulars and nine militia to stand their ground. And this they did until they were cut to pieces, with only a mere half-dozen surviving the attack (including Armstrong) by stumbling in the swirling smoke to cover in the swamp or the woods.

As October 20 dawned, Armstrong and the rest of the survivors straggled into camp. Harmar ordered a head count and to his surprise found that more than 120 men were missing, a large percentage he assumed having been killed in the meadow. The Regulars were angry over the conduct of the militia and Harmar publicly announced that if the militia repeated their shameful conduct, he would turn his artillery on them. The humiliated Hardin asked Harmar to let him take a force back to the battlefield, but Harmar refused. He decided to leave the dead where they had fallen, burn the rest of the villages, and return to Fort Washington.

This they did on October 21. But Harmar also wanted to avenge Hardin’s defeat. He did this by sending a detachment of 300 of his best militia infantrymen, 40 militia horsemen, and 60 Regulars under the command of Connecticut-born Major John Wyllys, a veteran of the American Revolution and a strict disciplinarian.

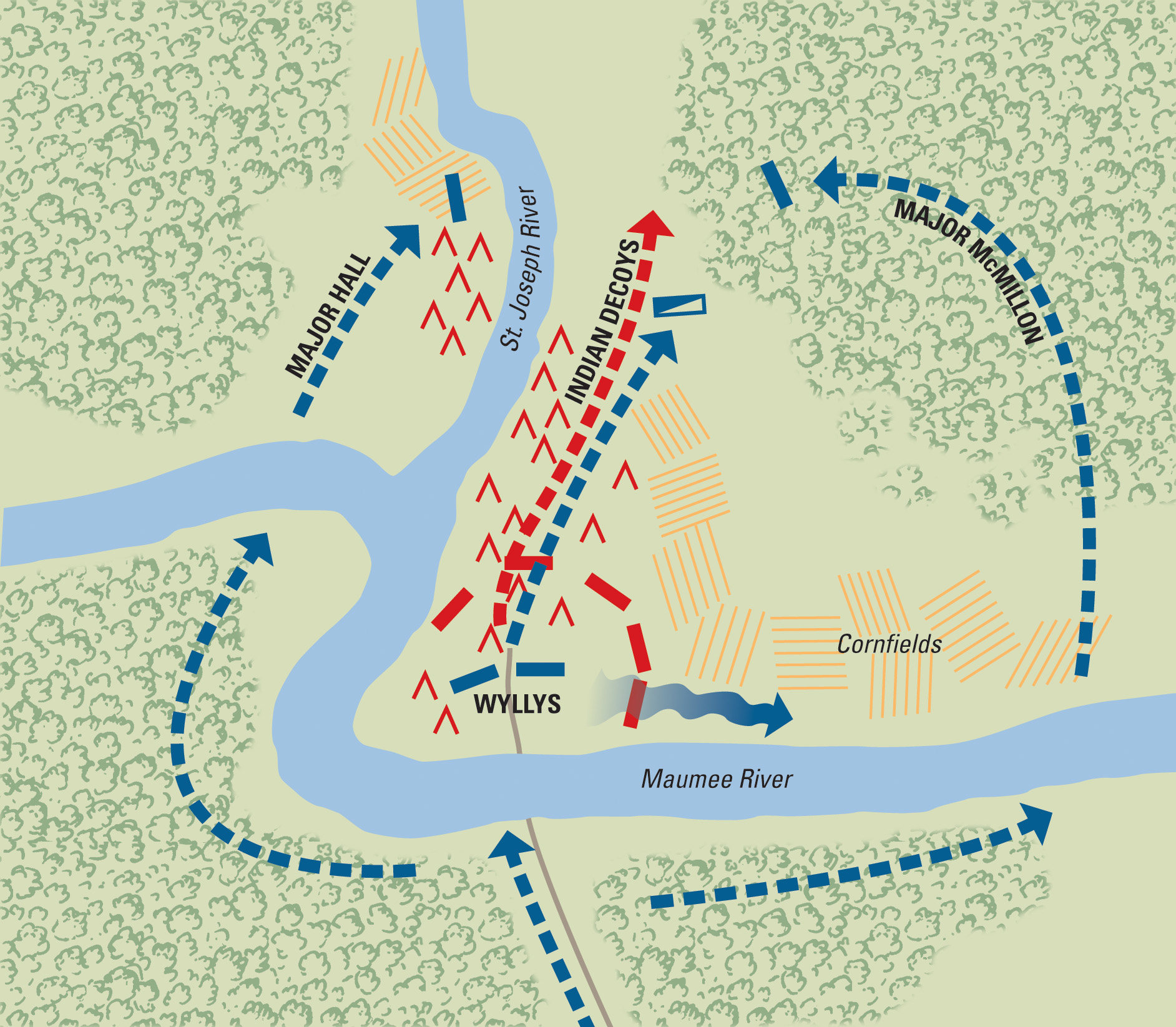

Wyllys’ force began moving out at two in the morning of October 22. His plan was simple: trap the Indians in the ruins by sending half his militia around to the left to block their retreat along the St. Joseph River and the other half right to close the escape route down the Maumee. Once these two pincers were in motion, Wyllys would lead his Regulars and the 40 militia horsemen straight into the village. The attack was scheduled for dawn.

Once again, however, the attackers’ assumptions proved wrong. Again, the Indians (led by Little Turtle) detected the returning troops. With their numbers increasing daily and fueled by the victory just a few days previous, they were looking for a fight. The sudden American presence had prevented the gathering of all the Indians in the area but enough were on hand for Little Turtle to devise a trap.

By the day’s early first light, Wyllys’ column approached the ford on the Maumee River near Kekionga. When his horsemen were almost across the river, Indian musketry hit into them from the opposite shore. Men and horses fell into the water while the Regulars hurried to form a line of support on the other bank of the Maumee. To the far right, the flanking militia heard the gunfire and double-timed to the aid of the cavalry by outflanking the Indians. On seeing this new threat, the Indians broke off the fight and fled. The surviving horsemen reorganized and joined the charging militiamen to chase down these braves. Meanwhile, the Regulars reformed and gave chase also, not wanting to be left out.

Major Wyllys hurried his Regulars across the shallow river and into the remnants of Kekionga. When his braves reached a burned cornfield on the other side of the village, Little Turtle gave the signal for the real ambush—the warriors at the river had only been decoys. This time braves sprang from the bushes and immediately closed with Wyllys’ men in hand-to-hand combat. Upon hearing the sounds of battle, both flanking militia units rushed toward the ambush site. But it was too late; after a short fight with the militia, the victorious Little Turtle and his braves escaped with very light losses—eyewitnesses put the figure at about 40 Indian bodies on the field. But for the Americans it was another costly defeat with only 10 Regulars surviving (Wyllys was also killed). After failing to bury the dead and even leaving some of the wounded behind, Colonel Hardin took charge of the column and quickly rejoined Harmar and the main body.

Harmar (having lost 183 men killed and many wounded, nearly 13 percent of his force) fully expected to run into a virtual wall of Indians on his withdrawal to Fort Washington (Indian strength stood at about 700 braves) but fate interceded. The evening after the battle there was an eclipse of the harvest moon, which some of the tribes took as an omen of great losses if they fought anymore at that time. They chose not to follow up their victory but instead let Harmar’s column return to Fort Washington unopposed.

After returning to Fort Washington, Hardin, Harmar, and St. Clair deemed the campaign a success in letters to Secretary of War Knox in spite of their losses. They estimated Indian casualties at between 100 and 127. Harmar might well have been able to justify his claim of destroying Little Turtle’s headquarters if he had not broken up his army and had exercised more personal control over the tactics and discipline of his unit commanders. As it was, one historian notes, “Only three-eighths of Harmar’s men took part in any fighting, and four-fifths of the Regulars and one-fourth of the militia who saw action were killed.”

But the fallout from the disastrous expedition began almost immediately. Militia leaders criticized Harmar for being drunk and for his lack of courage and effectiveness, while Regular officers blasted the militia’s cowardice and lack of discipline. Many Americans started to ask how savages could have inflicted such a defeat on an American army.

It was clear to everyone both in the Congress and the Washington administration that further steps needed to be taken to achieve security in the Northwest Territory. The subject of security took on more importance in light of Kentucky’s imminent step into statehood.

Meanwhile, the Indians, still emboldened by their victory, decided to carry the war to the entire Ohio Valley and even to the western frontier of Pennsylvania. That winter of 1790-1791 was to be the bloodiest on the frontier. This escalation of warfare in the West galvanized members in Congress to the notion that force would be needed, and Washington and Secretary Knox concluded that another expedition must be made against the Wabash Indians. Both Washington and Knox further agreed that this new expedition would require an increase in the Regular Army. To avoid the arguments and clashes in regard to a standing army, both men found a middle ground between the Regulars and militia: the use of levies or short-term volunteers.

The use of levies would serve a number of purposes: First, they would enlist only for the duration of the campaign; second, their use wouldn’t compromise a standing army but they would still be under federal command and discipline and thus more reliable than the militia; and last, they were more economical than either the Regulars or militia.

This new force would be built by adding one regiment of Regulars and by raising the rest as levies. By the time it adjourned in March 1791, Congress not only had approved Knox’s proposal but also had authorized funding for a second regiment of Regulars, 2,000 levies for six months, and the calling out of the militia for six months. Both the administration and Congress wanted an army large enough not only to force the Indians to sue for peace but to ensure continued protection of the Northwest Territory by building and manning a major fort in the heart of Miami territory. With this proposal, both believed they had the means to subdue the Indians.

Meanwhile, Harmar was facing a windfall of criticism for his poor leadership and performance. He demanded a formal inquiry to clear his name. Knox approved and a Court of Inquiry convened at Fort Washington. First, all the witnesses and deposers agreed that no one had seen Harmar “in a state of intoxication.” Second, they all praised Harmar for his conduct during the campaign. Thus they favored the notion that errors in judgment and poor battlefield performance lay not with Harmar but with the militia officers and the cowardly actions of their men.

The same witnesses testified that many of the militia were both poorly trained and ill-equipped for their mission. And to add insult to injury, several officers said they believed that if the militia had been ordered to return to the battlefield, they would have refused. This, according to one of the witnesses, Captain Boyle, accounted for General Harmar’s lenient treatment toward the militia. Another witness, Captain Armstrong, was more vocal and bitter in his assessment “that had the general ordered the army back to the battlefield and a serious Indian attack taken place, the militia would have deserted us in fifteen minutes, and left the Regulars and their artillery to be sacrificed.” The Court cleared Harmar and generally approved of his actions.

Meanwhile President Washington and Congress elevated Governor St. Clair to the rank of major general and leader of the new expedition. His selection wasn’t just political; he knew the region and its problems, and he had already forged links with leaders in the Northwest Territory. The retention of his governorship gave him both political and military clout.

After St. Clair’s appointment, President Washington met with him to give him advice based on his own painful experiences with the Indians. Washington summed it up in three words: “Beware of surprise.” He further said, “Trust not the Indian, leave not your arms for the moment, and when you halt for the night, be sure to fortify your camp—again and again, General, beware of surprise.”

When Washington had finished, Knox followed up with his own written brief to St. Clair, stressing discipline. He emphasized that retaining unit cohesion and mutual support could overcome the Indians, who fought as individuals. But Knox’s widely held belief that disciplined valor would always triumph led to a dangerous underestimation of the enemy.

St. Clair was eager to come to grips with the Indians, whom he knew were the Shawnee and some other tribes aided by the British. Most important, though, at the age of 54 he wanted to achieve that great military victory that had eluded him since he left Scotland 33 years earlier. He left Philadelphia in late March 1791 to return to Fort Washington, but he was stricken with gout. His sickness forced him to stay in Pittsburgh for almost a month, not reaching Fort Washington until mid-May.

What he found shocked him. His sole Regular regiment, the 1st, which he had hoped to use as the core of his expedition, was reduced by veterans leaving the service. His other units that had participated in the 1790 campaign were hit by expiring enlistments, poor living conditions, shabby treatment, and meager pay ($3 a month). Taking these factors into consideration, one can see why many weren’t willing to re-enlist. This is borne out by the fact that of the more than 400 men whose hitch ended in 1790, barely 60 re-enlisted. To make matters worse, rosters showed only 264 soldiers present for duty in forts along the Ohio.

By early summer, St. Clair’s struggle to organize an army was hampered by the low quality of both the recruits and the U.S. Army’s first Quartermaster, Samuel Hodgdon. The recruiting process wasn’t a careful selection of men but one that scooped from the gutters of Eastern society, gathering men unaware of and unprepared for the demands of army life on the frontier. Thus St. Clair would have to rely more than he had anticipated on the levies.

But that idea wasn’t approaching its promise. Enlisted principally from New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland, the levies were sent to Pittsburgh for training. Unfortunately, they were short on quality. Even the new commander of the levies, former Indian Commissioner Richard Butler, was deeply upset by what he observed as they drifted into Pittsburgh. In return, the levy officers and men resented having a politician for a commander rather than a seasoned Indian fighter. While they idled away their time in Pittsburgh, the levies were stricken by disease, dissension, and desertion.

By early June, the combined numbers of available Regulars and levies was only at two-thirds of the needed 3,000-man force. Knox cautioned St. Clair that he should seriously consider using the militia if the necessary number of recruits failed to materialize.

By the middle of summer, when the magnitude of the manpower problem became fully evident, another problem arose around the question of logistics. The Department of War was used to fielding a small force living and operating on the cheap, but St. Clair’s expedition was something that had never been attempted before.

“The Army Was Badly Clothed, Badly Fed, and Badly Paid.”

To make matters worse, Knox’s appointments to key positions were ill advised. The selections of Samuel Hodgdon as quartermaster and William Duer as the sole contractor to supply the army were both horrible choices. Hodgdon, a veteran of the American Revolution, had already showed glaring incompetence as a logistician during that conflict and Duer (a crony of Hodgdon) was more apt at the mechanics of corruption than he was at supplying St. Clair’s expedition. Couple this with the fact that Knox failed to supervise them, and the end result was a complete breakdown in the supply system. To put it in the words of a senior officer, “The army was badly clothed, badly fed, and badly paid.”

But there was some success. St. Clair sent, with Knox’s approval, Kentucky Brig. Gen. Charles Scott and 750 mounted troops on a series of raids throughout the summer of 1791. Scott, whose son had been killed under Harmar’s command, thirsted for revenge and he got it. Riding with him were Lt. Col. James Wilkinson and Colonel John Hardin, both veteran Indian fighters. Scott crossed the Ohio, feinted northward toward Kekionga, and then wheeled northwestward to strike the Wea villages along the Wabash. The Indians thought Kekionga was the objective and had assembled nearly 2,000 braves in that vicinity. Scott came upon defenseless villages and immediately destroyed them, their crops, and killed several Indians. His force took a large number of women and children hostage; they took the prisoners to a federal fort on the Ohio where they returned on June 15.

When St. Clair postponed the invasion until fall, he dispatched a second force, under the command of Wilkinson with 500 mounted horsemen, to repeat Scott’s ploy and keep the Indians off balance. It worked again with Wilkinson laying waste to the area around the village of L’Anguille and taking many prisoners. Compared to St. Clair’s force, both Scott and Wilkinson had demonstrated the superior effectiveness of a skilled force trained to act quickly and quietly.

Although disrupting and distracting the Indians and gaining valuable time, the two raids only solidified their resolve. At a grand meeting in early July, tribes debated whether to continue their war or open negotiations with the United States in an attempt to determine a mutually agreeable boundary for settlement while they were still in a powerful position. Many of them pushed for peace on such a basis but the Shawnee and Miami, their attitude freshly hardened by both raids, remained adamantly hostile. The result of the meeting was that several tribes opted out of the upcoming campaign while the Shawnee and Miami vowed to lead the others.

On August 7, the army was finally ready, if the word can be used, to march, with 718 Regulars and 1,574 levies “fit for duty” instead of the 4,000 St. Clair had anticipated. His expedition was already a month behind schedule when he sent forward elements of his force to Ludlow’s Station, five miles away at a crossing site over Mill Creek. St. Clair also sent a force under newly promoted Colonel Hamtramck 14 miles farther to the banks of the Great Miami River, where he was to build a stockade. This post, Fort Hamilton (modern-day Hamilton, Ohio), would be the staging area for the march as well as a depot of supplies and a strongpoint for the expedition to fall back upon. Construction began on September 11, when the area’s first frost began. It was completed by the end of the month. Accompanying the army north were a great number of wives, women, and children.

Gout again struck St. Clair, forcing him to stay at Fort Washington, and General Butler was placed in charge of the expedition. He left 300 men to garrison Fort Washington and immediately marched northward. His force now included 418 Kentucky and Pennsylvania militia as well as about 400 noncombatants. The expedition reached Fort Hamilton on October 2; Butler left his sick as well as troops to garrison the fort. By the time the expedition departed the fort on October 4, Butler had fewer than 2,000 men.

This expedition was aimed at conquest and occupation and thus required all the necessities for a force this large to not only fight but also to live deep in an inhospitable and undeveloped country. For this reason and because of continuing attacks of gout, St. Clair remained for a time in Fort Washington to address his extremely fragile supply situation.

But progress was slow. By the time St. Clair rode into camp, the expedition had only advanced 22 miles in five days! St. Clair chastised Butler for his “very gentile” marches, which caused strained relations. But even with St. Clair now on the scene, the expedition could make only seven miles a day and by the evening of October 12, the force was less than 50 new-road miles from Fort Hamilton. There, St. Clair ordered a halt and constructed another fort, Fort Jefferson.

More problems followed. The supply situation was critical. The weather was cold and rainy. Equipment was bad and morale low. The men knew they were being watched by Indians. And many of the levies began claiming their enlistments were up or soon would be. Three men were hanged for desertion.

Aware that the majority of levies were calling November 3 their last day of duty, St. Clair, sick himself with asthma and gout, left 120 sick men and two of his 10 artillery pieces at Fort Jefferson and marched northward on October 24.

On November 1, St. Clair halted again to let a supply train catch up. But then 60 Kentucky militia deserted and threatened to loot the supply convoy. St. Clair quickly ordered Colonel Hamtramck to take about 300 of the best troops from the 1st Regiment of Regulars to pursue the deserters and prevent the loss of the needed supplies and equipment. With Hamtramck’s departure, St. Clair’s expedition had shrunk to less than 1,500 men. More than 800 had been lost to death, disease, desertion, or detached duty in less than a month.

In mixed rain and snow, the baggageless force made 16 miles in the next two days before reaching a low crest of ground overlooking the Wabash River about halfway between what are now Celina and Greenville, Ohio. Exhausted, the army built fires to ward off the cold and cook their rations, but failed to build any defensive breastworks or place outposts to warn of any Indian attacks. There seemed to be no Indians around and the result was lax security. Beware of surprise, Washington had warned, but that seemed so long ago, before the men were cold, tired, and gaunt.

The mound itself made a good defensive position. An expanse of about six or seven acres, it overlooked marshy bottoms along the Wabash in front and swampy land on the flanks. Erroneously thinking he was encamped on a tributary of St. Mary’s River and only 15 miles from Kekionga, St. Clair planned to pause for a few days and await the return of Hamtramck’s column. Then, with his expedition rested and fed, he would march forward, seize Kekionga, and establish winter quarters.

Unknown to St. Clair, about 1,400 Indians under the command of Little Turtle seconded by a Shawnee named Blue Jacket were lying in wait two to three miles away in woods just past the Wabash. Little Turtle’s well-provisioned and fully informed force consisted mostly of Shawnee and Miami but also contained large numbers of Ojibwa, Delaware, Wyandotte, Ottawa, Chippewa, Mingo, Potawatomi, Huron, Eel, Weal, Kaskaskia, Kickapoo, Mississauga, Cherokee, Iroquois, Plankashaw, and even some white men.

Tittle Turtle, a member of the Eel tribe and now 44 years old, was dressed in robes with the front half of his head shaven and his hair long. He was accompanied by a young Shawnee brave called Tecumseh, who would later come to prominence during the War of 1812. Little Turtle’s plan was a coordinated assault on St. Clair’s camp at daybreak meant to encircle and annihilate the Americans. He instructed his warriors to concentrate their fire on U.S. officers and ordered his son-in-law, William Wells (see sidebar), and a select group of Miami Indians to pick off the artillery gunners as soon as their gun flashes gave away their positions.

During the night of November 3, Captain Slough scouted the perimeter of the camp. Observing several parties of Indians, he immediately reported this to General Butler, who said he didn’t need to awaken St. Clair, and so Slough assumed that Butler would tell St. Clair in the morning. Butler didn’t, with severe consequences.

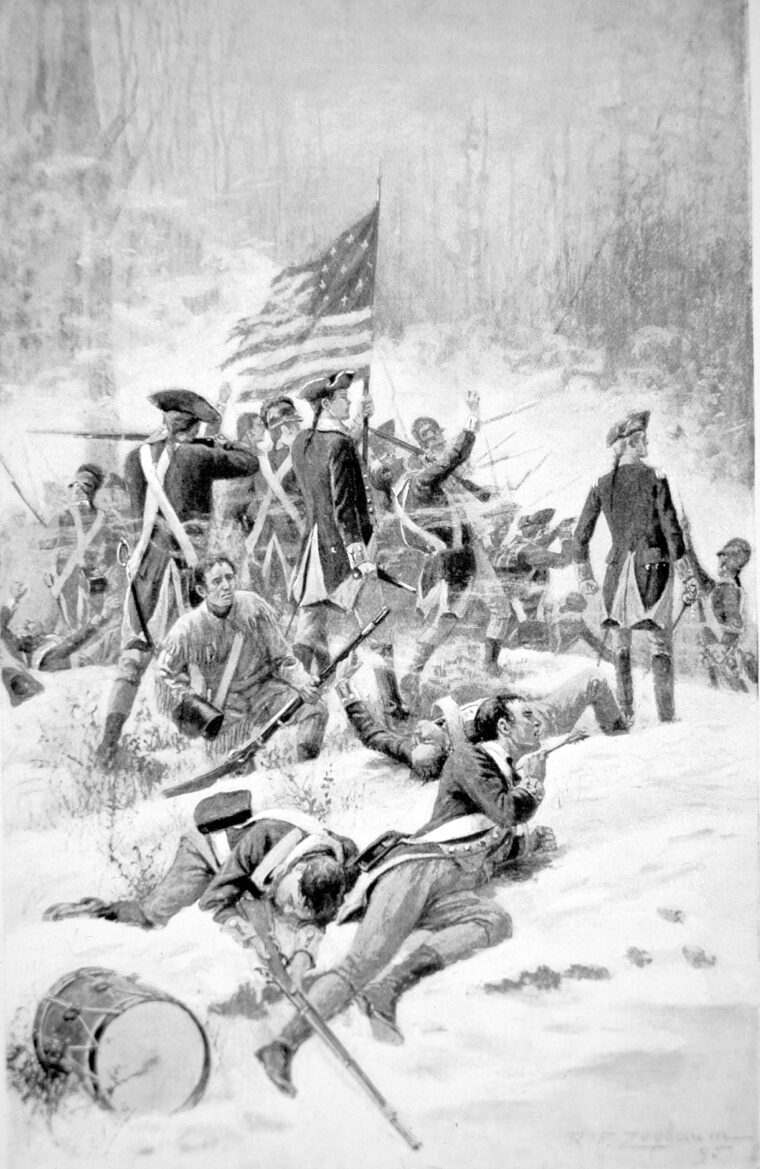

In the early morning hours of November 4, the Indians watched patiently as the soldiers answered roll call and were dismissed, many of them heading back to their tents to sleep. They watched the freshly stoked campfires blaze high and as the first light of the rising sun hit the trees, they struck. They let out spine-chilling screams and charged the tents and bedrolls. Driving straight into the outposted Kentuckians came the main force of Miami, Shawnee, and Delaware. The remaining warriors divided into two wings, each rushing to get around the flanks of the encamped army to seal off any escape.

Their initial target was the militia, who were quickly routed and turned back with heavy loss upon the main camp, thereby throwing it into chaos. Using knives, war clubs, steel axes, and tomahawks, they stabbed, slashed, and cudgeled the dazed soldiers as they emerged from their sleep. Many soldiers never escaped from their tents.

Officers shouted over the din, trying to assemble and form their men. Drummers beat the alarm; artillerymen attempted to shift their guns not emplaced properly the night before. Women and children were screaming and hollering while distraught militiamen stopped only long enough to pick up some hot food that still lay cooking on abandoned fires.

The soldiers along the perimeter didn’t stand a chance, but those in the middle rallied around a half-dressed St. Clair. The rattle of muskets could now be heard throughout the encampment as the encirclement was completed. Sniping from behind trees and logs, the Indians poured a heavy fire into the packed and bewildered soldiers. Very little return fire came from the confused whites, for they were still not sure just what was happening to them. Men began to fall everywhere; a musket ball killed St. Clair’s horse as he was trying to mount. Cannon began booming, increasing the noise and adding to the thick, acrid smoke, but with no visible effect on the attackers. Gunners were aiming too high, harmlessly blasting tree limbs above the crouching braves. The morning air became dark with gunsmoke.

St. Clair, now moving on foot and in great pain, courageously exposed himself to the densest fire. While others around him fell wounded or killed, fortune smiled on him with only his uniform being hit by musket fire. But St. Clair’s personal bravery couldn’t undo the months of poor planning and lack of professionalism that he and others had exhibited. As the sun rose, he came to realize the seriousness of his situation: His force was surrounded by Indians, he had no breastworks or other defense, and his command was crowded into a tight area with no room to maneuver. Now and then an American panicked and darted into the woods, only to be followed by a grinning warrior who planned to hang the man’s scalp on his lodgepole that night. Some captured soldiers could be heard screaming in agony as Indians tortured them.

The Indians, moving stealthily from firing position to firing position, were taking a steady toll on the exposed soldiers, while suffering minimal casualties in return. As the grisly, one-sided attrition continued, the situation grew increasingly tenuous. St. Clair and others decided in desperation to launch a bayonet attack to push their assailants back.

After two hours of slaughter, St. Clair and Lt. Col. William Darke, a levy officer, led about 300 Regulars and levies in a bayonet charge over the Wabash, pushing some 300 yards before the attack lost momentum. The Indians had anticipated a counterattack and shot at them from the flanks and then closed back in to enter the American position through the gap left in the defensive lines. When St. Clair, Darke, and the men came upon the position where once the rear line of the artillery and noncombatants’ tents had stood, they were in shock.

Grotesque and Brutal Victory for the Indians

The dead and dying lay in macabre positions, all scalped. Many of the wounded had been thrown alive into the fires, and women and children also fell victim to the scalping knife. A shocked lieutenant of the 2nd Regiment reported seeing some of the women sliced nearly in half, with “their bubbies cut off,” and tossed to burn with “a number of our officers on our own fires.” The Indians had occupied the position for only a bloody 10 minutes or so. Only three of the women are known to have escaped and those children who weren’t killed were taken captive. It was becoming obvious to the beleaguered Americans that their opinion of the Indians’ ability to wage war had been all wrong. Their foe this day fought not only with brutality and bravery, but also with discipline and unity. The more professional force on the field was Indian not white. Although outnumbered and outgunned, the Indians had the edge in training, discipline, morale, teamwork—and, above all else, leadership.

The uneven contest grew quickly more hopeless. Painted and shrieking braves pressed ever closer, nimbly avoiding various efforts to beat them back. Many stunned soldiers simply stopped trying to fight, standing like cattle to be shot down from point-blank range. The army had ceased to be. What was happening was no longer battle, it was massacre. St. Clair realized that further resistance was futile—but surrender was tantamount to suicide. The Indians would take no prisoners.

Realizing that if they stayed, they would be killed, both St. Clair and Darke gave the order to attempt a breakout to Fort Jefferson, 29 miles south. Men unable to move would have to be abandoned, which included badly wounded Maj. Gen. Richard Butler. As these soldiers retreated they came across dozens of wounded and scalped Americans. One officer, sitting numbly on the ground, his head scalped, looked up wanly to ask his fleeing comrade if the fight was over. For soldiers like him it was. The battle had lasted about three hours.

The first wide-eyed survivors staggered that night into Fort Jefferson. Many had thrown their muskets away and were in a state of shock. St. Clair escaped on a pack horse and assembled as many men as he could in the retreat south. Colonel Hamtramck’s unused 1st Regiment of Regulars helped recover the stragglers coming into Fort Jefferson over the next few days.

Although some Indians did follow and harass the soldiers, Little Turtle made no effort to pursue them. Having captured the American position, the Indians began plundering it. That evening they marked out a piece of land about five hundred yards long, stripping all the bordering saplings and covering them with red-painted symbols signaling victory and life. They then drank captured whiskey, ate roasted cattle, and split up the clothing and personal effects they had taken from the bodies.

One of the Most Crushing Defeats in U.S. Military History

The scope of their victory was astounding: St. Clair’s military casualties totaled 900, including 637 dead and 263 wounded, or 65 percent of his force. It was one of the most crushing defeats in U.S. military history, and the worst by far of the Indian wars. In addition, almost half of the estimated 400 camp followers, made up of wives, children, and prostitutes, were killed. Fewer than 500 of the 1,400 soldiers escaped. Little Turtle’s casualties amounted to only 21 dead and about 40 wounded.

Two main consequences followed St. Clair’s defeat. First, the British Army was encouraged in its policy of making war on the United States by proxy, and not only increased the flow of war material to the Indians, but began sending “advisors” with them on war parties. By doing so they raised the proxy war very nearly into a real war, which for political reasons Parliament and Congress refused to admit actually existed.

Second, Congress agreed to raise another army and to provide a general who had actually won a battle before. They chose Anthony Wayne, whose vigor—some said rashness— in the American Revolution had gained him the nickname “Mad Anthony.” He avenged the U.S. travesties at Fallen Timbers in 1794.

Little Turtle, in 1790-91, inflicted more casualties on the U.S. Army than any other Indian war chief before or since. In just two battles, traditionally known as “Harmar’s Defeat” and “St. Clair’s Defeat,” he slew some 820 U.S. soldiers. In contrast, the best that all the great warrior peoples—the Apache, Sioux, Cheyenne, Nez Perce—could inflict on the U.S. Army in the 26 years from 1866 to 1892 was to kill about 920 soldiers, only about 12 percent more than Little Turtle had accounted for.

Yet today Little Turtle is hardly remembered, and certainly never numbered among the great Indian warriors.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments