By Jeremy E. Green

By the year 1798, the First Coalition was collapsing. Only Britain remained as France’s implacable foe. With the advent of relative peace, the governing body of France, the Directory, ever in need of cash, now sought new means of employment for the army and its general, Napoleon Bonaparte. Also for the first time since 1792, the war’s revolutionary zeal and national survival had given way to overt imperialism. The Directory’s desire for treasure and territorial aggrandizement coincided perfectly with a certain French general’s private thirst for military glory and political advancement.

The lure of the East had been considered by French governments for the previous 50 years. Louis XIV and his successors had maintained friendship with the ruler of the Turkish Empire, the Ottoman Porte. Merchants from Marseilles handled many commodities from the East such as rice, coffee, sugar, and cotton.

“The Fountain of Glory”

Napoleon’s reasons for attempting the expedition were many. First, the pacification of Italy was nearly complete and his proconsular authority would be terminated by the Directory—he would be one among many unemployed generals. He was also a dreamer who confided to his friend and secretary Bourrienne: “I see that if I linger here I shall soon lose myself. Everything wears out here; my glory has already disappeared. This little Europe does not supply enough of it for me. I must seek it in the East, the fountain of glory.”

In Charles Talleyrand, a new foreign minister in the Directory, Napoleon found an ally for an Egyptian campaign. In addition, French commercial interests outlined the importance of profits to be obtained from colonies. Thus on April 12, 1798 the Directory instructed General Bonaparte to seize Malta and Egypt; dislodge the English from their establishments; overthrow the corruption of the ruling Mamelukes, who badly ruled for Turkey; pierce the Isthmus of Suez; improve the living conditions of the native Egyptians; and maintain good relations with the Porte (Sultan of Turkey).

Preparing the Expedition

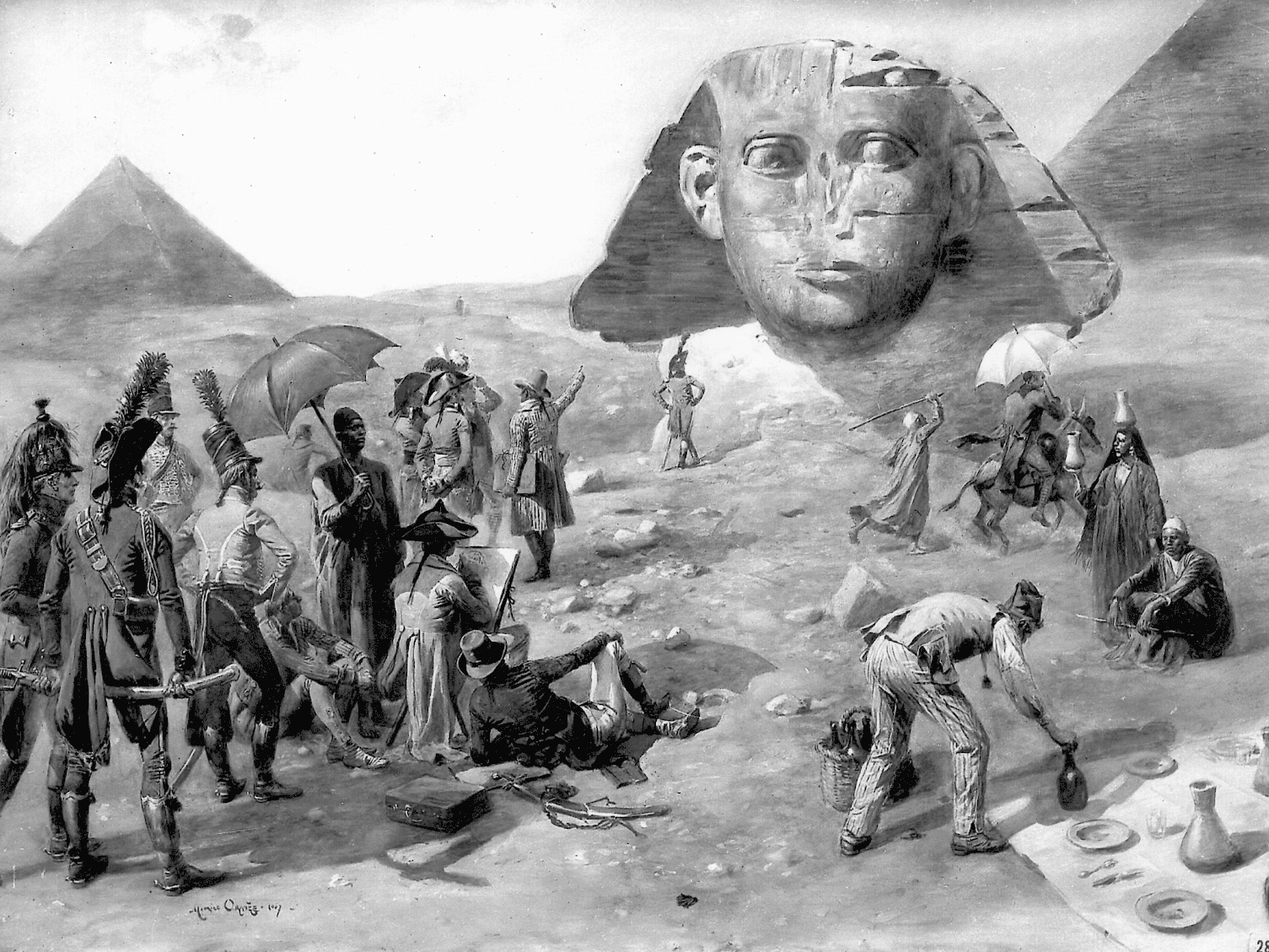

In the 10 weeks following the Directory’s approval, an energetic General Bonaparte was busily equipping his troops, assembling transports, outfitting warships, recruiting sailors, and enlisting a commission of civilian experts: engineers, scientists, aeronauts, artists, archaeologists, economists, pharmacists, surgeons, writers, musicians, interpreters, and printers to accompany his expedition. As a newly elected member of the Institute of Arts and Sciences, Napoleon felt deeply honored and always used this title in his proclamations. In a letter to Camus, president of the Institute, Napoleon wrote: “True conquests—the only ones that leave no regret behind them—are those that are made over ignorance. The most honorable, as well as the most useful, occupation for nations is the contributing to the extension of human knowledge.”

Consequently, Napoleon consulted with the engineer specialist, General Caffarelli, and the brilliant scientist Berthollet, in selecting 167 savants, such as the distinguished mathematician Monge, balloonist Conte, doctors Larrey and Desgenettes, and the great artist Denon. It was to be this last group of civilians who would achieve the ultimate victory of the campaign. Their scientific research and discovery would prove to be the most lasting and beneficial accomplishments, because the French enlightened the Western world to the ancient history of the pharaohs and the modern possibilities of a canal through Suez.

Most of the soldiers Napoleon mobilized derived from his Army of Italy. He had successfully molded these hungry revolutionary soldiers into an admirably disciplined, intelligent, and swiftly responsive mechanism. In addition to the army, navy, and scientific commission, there were women and children who were cantinieres, laundresses, and so forth. While most women were barred from the expedition, a few husbands and lovers succeeded in disguising their women and having them stow away on board. In this way, some three hundred women accompanied the armada.

Civilians included, the expedition totaled almost 38,000, outfitted with 60 field guns, 40 heavy siege artillery, a hundred day rations, 1,200 horses, and three hundred washerwomen. The French vanguard took the island of Malta (from the Knights Hospitallers, mostly French) on June 9, 1798. Working ever expeditiously, Napoleon had the island ceded to France and proceeded to liquidate the centuries-old state, establish the basis of new government, and confiscate the seven million francs in the treasury. He also abolished slavery and freed two thousand Turkish and Moorish slaves, an act he hoped would convince the beys (roughly,“princes”) of Tunis, Tripoli, and Algiers of his friendly intentions in North Africa.

The Campaign Begins

The entire armada landed at Marabout on July 1. By midday, with a toll of three hundred casualties, Alexandria was under French control. Immediately, proclamations were distributed announcing the coming of the French to be the will of Allah, and their purpose to free the Egyptians from their ancient servitude to the Mamelukes.

A terrible march toward Cairo ensued, the men suffering from thirst and a burning red dust that caused temporary blindness. At El Rahmaniya, the troops first saw the Nile and threw themselves into the river to drink. Napoleon then rallied them for battle. As the French played the Marseillaise, the Mameluke horsemen lined up for the charge.

Napoleon had each division form a square, six ranks deep, the center of the square to contain the cavalry, with the artillery placed at the corners. With a bloodcurdling cry, the magnificent horsemen charged headlong into the bayonet-bristling squares. The French answered with a barrage of cannon and rifles. The Mamelukes continued to circle the supporting squares looking for an opening and finding nothing but shot and steel.

Napoleon won at El Rahmaniya and proved that a modern, disciplined army could withstand a ruthless yet medieval enemy. But the bulk of the Mamelukes had escaped. The French marched on Cairo. Nearby Murad Bey waited on the left bank of the Nile, at the village of Embaba, which he had fortified. Ibrahim Bey was encamped at Bulaq to meet the French threat on the right bank. On the Nile, the Mameluke gunboats awaited the invader. Behind the formidable Mameluke line of battle loomed the Great Pyramids.

With a loud and inspiring voice, Napoleon addressed his men: “Soldiers, forty centuries look down upon you!” Placing all his confidence in his army’s ability to carry out his instructions, Bonaparte awaited the onslaught of the Mamelukes. The least weakness or panic could result in disaster. A break in the ranks and the impetuous Mamelukes, with dazzling speed, would have penetrated the French squares and carved a bloody path. The exhausted French were hungry, weakened by dysentery, demoralized, and fighting in an alien country. The Mamelukes, on the other hand, were well rested, in their own element, and enjoyed a numerical superiority of Murad’s six thousand Mamelukes and 15,000 foot militia allied to Ibrahim Bey’s 100,000 warriors. The French numbered 25,000 men.

Facing the desert was the French right, consisting first of Louis Desaix’s square, supported to the left rear by Jean Reynier. Desaix had also sent a detachment of cavalry and grenadiers to occupy the large village forming the extreme right of the French line. Honore´ Vial and Andre´ Bon were flanked to the left, parallel to the Nile, and opposite the town of Embaba. In the center, standing in reserve, was the division of Charles Dugua. Bonaparte and his staff found shelter within this square. At 3:30 pm the Mamelukes, with their long, bejeweled scimitars glistening in the sunlight, charged toward the French right with a terrifying yell, taking Desaix and Reynier almost by surprise. The squares closed up and soon fire-fringed rectangles greeted the torrent of horsemen. Only their discipline and good generalship would win this battle for the French.

After hitting these two squares, the Mamelukes plunged on to the rear where Dugua’s square greeted them with a firing howitzer. Soon the galloping horsemen swung round and swept back to the village near Desaix. The small French garrison held off the Mameluke horde until reinforced from Desaix’s division. Meanwhile, Vial and Bon, covered by the French flotilla’s guns firing from the Nile, prepared to storm Embaba. At first, Egyptian cannon held back this French attack. But these guns were positioned onto unmovable carriages and could not penetrate the continued French attack.

Recovering their élan, the soldiers of Bon’s division spread out into a number of attack columns supported by three small squares of General Rampon. In a few minutes, Bon’s men stormed their way into the village, and as the garrison of two thousand Mamelukes tried to escape up the Nile, Aguste Marmont rushed a demibrigade forward to seize a defile at the rear of the village. Their retreat cut off, the Mamelukes turned in desperation toward the Nile and attempted to swim across to join Ibrahim Bey’s watching multitude. By most counts a thousand drowned and six hundred more were shot down. By 4:30 pm, the battle was won and Murad Bey, with his three thousand surviving cavalry, fled toward Giza and Middle Egypt.

Napoleon Bonaparte had at last gained his decisive victory. The victorious French had accounted for two thousand Mamelukes and several thousand more fellahin or foot soldiers for a loss of 29 killed and 260 wounded.

That night, Ibrahim Bey abandoned Cairo and retreated east toward Syria. The remaining sheikhs and imans surrendered the city, and on July 24, Napoleon Bonaparte entered the capital of Egypt.

Napoleon Loses his Fleet

This was his last full measure of personal happiness, because on July 25, Napoleon’s trusted aide-de-camp, Andoche Junot, inadvertently revealed that Madame Bonaparte, in the absence of her husband, had been unfaithful to him and had taken as her lover a young officer named Hippolyte Charles. All Paris knew of the scandal.

Napoleon’s grief was terrible. He truly adored his Josephine and, for a while, thought of abandoning his military career completely and entering secluded retirement. His personal happiness destroyed, all Europe would be affected by Napoleon’s growing selfishness, suspicion, and egocentric ambitions.

Napoleon was still reeling from the shock of his wife’s infidelity when, at 10:00 pm, August 1, a great flash of light and a tremendous explosion visible from 25 miles away shook him to the reality that English Admiral Nelson had at last caught up with the French squadron anchored off Aboukir Bay. Nelson pulverized it (see Military Heritage April 2000 issue).

Upon receiving the official news of the disaster, Napoleon put the best possible spin on the result, telling his officers: “Well, gentlemen, now we are obliged to accomplish great things: We shall accomplish them. We must found a great empire, and we shall found it. The sea, of which we are no longer master, separates us from our homeland, but no sea separates us from either Africa or Asia.”

Rebellion in Cairo

Napoleon still had other major problems. Forced loans from businesses, confiscated property, levies, and such brought in some money, but the soldiers’ pay remained in arrears. Needless to say these practices to raise cash, as well as the French refusal to adopt Islam, increased the resentment of the Egyptian populace.

The forced loans, requisitions, and fines were annoying, but for the Egyptians, seeing their wives and daughters walking in the streets unveiled was the ultimate disgrace. Many revolted on October 21, taking the French by surprise.

Soon General Francois Victor Dupuy, the commandant of Cairo, was killed and corpses were everywhere. The insurrection quickly gathered momentum. On the following day, a soldier named Sulkowski, one of Napoleon’s favorite aides-de-camp, was killed, along with most of the Guides, or security troops, in his escort. According to General Nicolas Desvernois, the rebels threw Sulkowski’s corpse to the dogs to be devoured. Napoleon’s order to General Bon, who replaced the dead Dupuy, was simple: “Exterminate everybody in the Mosque, El Azhar.” Thus the guns of the Citadel began their bombardment of the Mosque, and all of Cairo erupted. Bombs rained everywhere.

The rebellion collapsed. Three hundred Frenchmen were dead, while the rebels numbered two to three thousand. Yet, there were no reprisals. Napoleon, who could show rage and fire in battle, displayed mercy and amnesty in victory. The sacred books of El Azhar were returned to the Mosque. Only those rebels found with weapons and guilty of actually inciting the rebellion were beheaded, but in the dead of night and in secret.

Napoleon and Pauline Foures

On December 17, 1798 the lonely Bonaparte met the beautiful Pauline Foures at the newly opened Tivoli. She was 20 and lovely. General Bonaparte ordered her husband Lieutenant Foures to proceed to Rosetta, then to Malta, and then on to Paris to convey certain unimportant dispatches. He was then to remain in Paris for at least 10 days. Within a few days of her husband’s departure, the vivacious Pauline became known as Cleopatra, and occupied the mansion next to Bonaparte’s.

Everything seemed ideal except the poor husband never reached Paris, let alone Malta. After leaving Alexandria, the lieutenant’s ship was captured by the British blockade. The English captain was aware of the affair and had a sense of humor, so he sent the bewildered Foures back to Alexandria. The dedicated officer made his way back to Cairo only to find his wife in bed with his Commander-in-Chief. The unfortunate husband was outraged, the wife embarrassed and terrified, and the General infuriated at the British who had made him appear so ridiculous.

Pauline obtained a fast divorce and Bonaparte promised his love that he would divorce Josephine and marry her. Unlike Josephine, Pauline could bear him a child. Once divorced, the new Cleopatra became Napoleon’s official mistress, presiding over dinners attended by his aides. This romantic interlude lasted two months, for by then Napoleon was setting out for Syria, leaving his beloved in Cairo.

During his liaison with Pauline Foures, tragedy struck. In December, the dreaded plague broke out, further depleting the dwindling French forces. To instill courage in his men and in the doctors whose fear made them abandon the plague victims, Napoleon publicly went to the hospital, where he personally handled the sick and the infected. This gesture had a great impact; it encouraged both the sick and healthy soldiers and even the embarrassed physicians to return to their duties. However, many men fell victim to the dread disease.

The March to Syria

In the midst of this horror, the army began its march for Syria (that is, an area encompassing Syria, as well modern Israel, Lebanon, and Jordan). With fortune, he could conquer this land and march on Constantinople, for Turkey had declared war on France. To augment his host, Bonaparte incorporated naval crews, Mameluke slaves, Egyptian civilians, and even Negroes into each French battalion, not as separate units, but as comrades-in-arms.

Djezzar Pasha of Syria, also known as “The Butcher,” had raised a large army and was preparing to invade Egypt by land in the spring of 1799. An Anglo-Turkish landing by sea was also a strong possibility. Napoleon calculated that the best defense was to attack Djezzar rather than to wait for him, defeat him before spring, and return to Egypt in time to prevent an attempted landing. This was an extraordinarily ambitious plan even for the ever-talented Napoleon. Meanwhile no news was reaching Napoleon from France through the British blockade. In fact, France was at war with most of Europe and exceptionally preoccupied.

On February 10, 1799, Napoleon left Cairo to invade Syria with 13,000 men in four divisions commanded by Jean Kleber, Bon, Jean Reynier, and Jean Lannes; eight hundred cavalry under Joachim Murat; 1,755 sappers and artillerymen; Jean Baptiste Bessieres’ four hundred Guides; and the 80 men of the Dromedary Corps. Distinguished members of the Scientific Commission also made the march.

Napoleon reasoned that the campaign would fall into two stages: a rapid march through the Sinai Desert up the coast of Palestine, and then a hard struggle for Acre. As usual, speed was to be the ingredient of success.

The Frenchmen’s first action was at El Arish. In a daring surprise night attack on February 14-15, Reynier took five hundred enemy lives for three of his own, but the siege then lasted 10 days. The strength of the solid masonry fort at El Arish was to eventually cost Napoleon the entire campaign. At last, the garrison agreed to terms. In a magnanimous gesture, Napoleon granted clemency, provided the defender would no longer make war on his army.

On February 24, the army captured Gaza where the men replenished their food and ammunition. But the weather was damp, raining, and cold, and even the hardy camels died from exposure. On March 7, the onslaught for Jaffa began.

Led by the intrepid Jean Lannes, the French assault was a great success. General Bonaparte sent his aide-de-camp, Alexandre Beauharnais, who was also his stepson, to report what was happening. The enemy garrison was willing to surrender if granted quarter; otherwise it would defend itself to the last.

Soon this mass of four thousand men entered Napoleon’s camp. Having discovered among the garrison’s prisoners former prisoners from El Arish that he had previously freed on their word to stop hostilities, Napoleon was faced with a great problem. In a tone of profound sorrow, Napoleon confided to Bourrienne, “What do they wish me to do with these men? Have I food for them? Ships to convey them to Egypt or France? Why, in the Devil’s name, have they served me thus?”

For six days Napoleon and his generals deliberated as to what course of action should be taken with these prisoners who had violated parole. The increasing complaints of the French soldiers at seeing their meager rations given to their enemies was creating a desperate fear of revolt by the army. It was impossible to send them to Egypt because the army was already too small to afford an armed escort and again there were too few provisions. The general fervently hoped that his flotilla would arrive and take the prisoners aboard. But his hopes were in vain. Granting another parole was out of the question, because there was a strong possibility that, once again released, the men would proceed to Acre just as they had come to Jaffa.

Finally, the order for shooting the prisoners was given. As if in retribution, on March 8, the dreaded plague descended upon the French army. Napoleon, who could be so ruthless in battle showed extraordinary compassion, when on March 11 he personally visited the plague victims at Jaffa, administered to the sick, and helped to carry the hideous corpse of a soldier. This saintly and heroic act achieved its purpose and the army rallied its confidence in their brave leader.

The Siege of Acre

The French army assembled before Acre on March 19, just when Napoleon learned the French flotilla carrying the heavy siege guns had been captured by the British Navy. Meanwhile, the English naval commander, Sir Sidney Smith, had landed Napoleon’s former classmate, a French emigré engineer officer named Phelippeaux, in Acre to improve the defenses and to give Djezzar Pasha support to withstand the French attack. The combined strength of Phelippeaux, Commodore Sidney Smith, and “The Butcher” was a formidable trio of enemies to withstand the genius of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Acre had very thick walls and was built on a peninsula surrounded by the sea which Sidney Smith controlled. In the huge towers was placed a tremendous array of artillery, as well as the newly captured French siege guns—the French were to be treated to a taste of their own artillery. In addition, because the English controlled the sea, the occupants of Acre were well supplied and reinforced, while the assailants had no supply bases. The French even resorted to collecting enemy cannon balls for their own use.

With the fortifications of Acre made as invincible as possible, the full implication of the 11-day delay at El Arish now became obvious. Had Napoleon arrived at Acre on any day before the 15th, he would have taken the fortress easily. Having arrived on the 18th, he now faced an impregnable fortress that could fire upon his troops with their former heavy siege artillery.

On March 28, the French attacked and at first drove back the Turks, having made a breach in the wall. But the fiery Djezzar Pasha rallied his men and soon the French were repulsed. The French assaulted again on April 1. Nearly every man involved was either killed or wounded. During this period, Djezzar Pasha lived up to his name—“The Butcher” massacred hundreds of French and Christian prisoners within the walls of Acre. Their bodies were thrown into the sea where they washed up on the shore.

To worsen the situation, a ring of enemy Turks began to encircle the French. Djezzar Pasha’s appeal for aid had brought on the Pasha of Damascus and his army. On April 5, a reconnaissance detachment under Charles Junot repulsed a cavalry force several times its superior, near Nazareth. Nevertheless, Napoleon realized the apparent strength of the seven thousand men of the Army of Damascus, and ordered Kleber, with 1,500 men, to Junot’s assistance.

On the 11th, Kleber’s force, in its turn, defeated six thousand Turks near Canaan. To ensure the safety of his flank, Napoleon dispatched the dashing Joachim Murat with two battalions to seize the important crossing of the Jordan to the north of Lake Tiberias on April 15. Murat’s men came upon the enemy and in splendid fashion routed the five thousand enemy troops without a loss.

On April 16, the day following Murat’s spectacular exploit, Kleber and his 1,500 men clashed with the Pasha of Damascus and his army of 25,000 cavalry and 10,000 infantry near Mount Tabor. Despite a disadvantage of over 17 to 1, Kleber fought a great defensive action, as the 25,000 horsemen galloped toward his squares. For 10 hours the French force grimly held on, though ammunition became dangerously low.

The situation appeared desperate, when, as if by a miracle, Napoleon himself appeared at the head of Bon’s division. The Commander-in-Chief had learned of his subordinate’s danger and, marching 25 miles, charged into the rear of the Turkish army. After a few choice cannon shots, the Ottoman army scattered. The Battle of Mount Tabor was a monumental victory. Amazingly, when roll call was sounded, Kleber learned that only two men had been killed and 60 wounded in this grueling 10-hour struggle.

Despite his achievement at Mount Tabor, Napoleon still faced the stalemate at Acre, where French morale remained low. Every day the plague claimed new victims and the army continued to run low on supplies and ammunition. To remedy the increasing shortage of cannon balls, Napoleon offered a cash reward for every cannon ball retrieved. The French were busy developing elaborate trenches and fieldworks when a sortie by the garrison was driven back on May 7.

Meanwhile the French were cheered by the arrival off Jaffa of the long-awaited siege train. These guns were dragged overland with great difficulty, but soon they were in place to bombard “The Butcher” and destroy his forces. From May 1 to May 10, Napoleon launched five more desperate assaults on Acre. Only the attack of May 8 vaguely resembled success, when the French Ajax—Jean Lannes—fought his way into the town at the head of two hundred grenadiers, only to discover that the defenders had constructed impregnable interior defense works.

Displaying his usual dash and courage at the head of his charging men, Lannes was severely wounded. After 25 hours of continuous fighting, the French relinquished the battle. After Kleber failed in one of his attacks, Napoleon had to face the grim reality of the situation; he was beaten and without Acre, there was no real prospect for conquering Syria. After 63 days of constant work, and eight costly assaults, the French Commander-in-Chief gave the order for the retreat back to Egypt.

A Triumphant Retreat

General Bonaparte tried to conceal the reality of defeat from the Egyptian people by issuing victorious proclamations congratulating his soldiers on their victories at Mount Tabor, Gaza, Jaffa, Haifa, and surprisingly, Acre. Napoleon’s explanation for his army’s return to Egypt was that “hostile landings may be expected.”

The retreat, however, raised many problems, such as the transport of as many as 2,300 wounded, the heavy siege guns, and remaining artillery. In addition, enemy cavalry made constant harassment. The army spiked and abandoned artillery, and somehow evacuated its wounded. At Jaffa, the remaining plague victims were offered the alternatives of joining the retreat or of taking poison to avoid capture. Mercy killing for the immovable wounded cases became the norm and the morale of the men suffering from lack of food, supplies, and water sank to a new low. Only the iron will of their commander drove them on.

The Syrian Campaign destroyed the Army of Damascus, but that was all; the remaining objectives of the campaign never materialized. The cost was high—1,200 men killed, a thousand dead of the plague, and 2,300 seriously wounded or fallen ill, leaving only two thirds of the original fighting force. Although Napoleon failed to conquer Syria and the British were masters of the sea, General Bonaparte, that master of propaganda, staged a triumphal victory march through Cairo on June 14.

The Directory, in need of all its forces, had sent word to the French Commander for his return with his army to France. The French fleet together with Spanish fleet, would supply Malta and Corfu and then resupply the French or evacuate them from Alexandria. Unfortunately, the Spanish naval commander refused to cooperate with the French naval commander and a rare opportunity of French-Spanish naval supremacy over the English in the Mediterranean was lost.

But Napoleon was busy constructing his own plans. On June 21, he issued secret orders to Admiral Honore Ganteaume to prepare the frigates, La Murion and La Carriere, for immediate sail. Commodore Sydney Smith had succeeded in closing the Orient to General Bonaparte, but he unwittingly had just opened all Europe for the next 15 years to the Age of Napoleon.

The Battle of Aboukir

On July 11, a Turkish fleet, escorted by Smith’s squadron, anchored off Aboukir Bay. Soon General Mustapha Pasha and 15,000 Turkish soldiers were swarming ashore. By July 24, Napoleon’s 10,000 men were converging on Lake Aboukir. The last great battle of the Egyptian campaign was about to take place. Napoleon decided to attack immediately without waiting for Kleber’s division. He remembered how costly the delay at El Arish had been in thwarting him at Acre. There would be no repeat of that here at Aboukir. Napoleon was confident that his thousand cavalry led by the brilliant Joachim Murat could destroy the enemy which was strangely lacking Turkish cavalry, still on board the transports.

The land Battle of Aboukir took place on July 25. It was markedly different from those of the Pyramids or of Mount Tabor in that the French cavalry now became the dominant force. Under the leadership of that fire-eater Lannes, the French infantry battled its way through three successive lines of Turkish entrenchments.

The final coup de grâce was delivered by the most famous cavalryman of the age. Joachim Murat, who was fast becoming Napoleon’s right arm, found the knowledge of the ground acquired the previous July of the greatest assistance. At midday, the flamboyant Murat, at the head of his cavalry, swept down upon the Turks with such ferocity that the terrified enemy ran before them. In the midst of the smoke appeared the figure of death, in the shape of General Murat, his horse rearing and nostrils spurting blood, with Murat swinging his saber high above his long, flowing, jet-black hair.

Finally, the great French horseman came upon his archrival, Mustapha Pasha, who quickly aimed his pistol and shot this French war god in the cheek. Despite this almost fatal wound, Murat flashed his saber at the Turkish leader and disarmed him of his pistol, plus some fingers. Mustapha Pasha surrendered and soon the Turkish headquarters was captured along with many senior officers. With men like Murat and Lannes, Napoleon would conquer Europe.

Napoleon’s Return

Napoleon’s Return

On August 22, the small French squadron set sail for France. He left an outraged General Kleber, who had suddenly been given command of the remaining troops but with a treasury in debt and without even a day’s notice of his commander’s departure.

On October 9, 1799 Napoleon arrived in France. He was hailed a hero, as news of his victory at Aboukir had arrived four days earlier. The news of his return traveled quickly to Paris where the Directory met to decide the best way to deal with the Conqueror of the East. Meanwhile, the panic-stricken Josephine raced by the coach to meet her husband before he saw his family, who were determined to ruin her.

Unfortunately for the nervous wife, she took the wrong road and ultimately arrived home two days later than her celebrated husband, who had thrown her baggage into the hall. Although insistent that she must go, the “Conqueror of Europe and Asia” fell sway to her feminine wiles and the begging of his stepchildren, Eugene and Hortense. The next morning, when Lucien Bonaparte came to visit his brother, to his dismay he found husband and wife snuggled in bed together.

By November the Directory was in disarray and the Conqueror of Egypt was stepping into leadership of the state. A coup d’état in November set up a new form of republic called the Consulate, with Napoleon as the First Consul.

For Kleber, there remained one more year of endless effort to bring himself and his homesick men back to France. He even attempted to negotiate an armistice with Sir Sidney Smith and the Grand Vizier of Turkey. These negotiations failed, however, and Kleber realized just in time that he had been duped. The new Commanding General met the Grand Vizier’s 30,000 soldiers at Heliopolis on March 20, 1800 and won a spectacular victory, despite his troops’ desire to return home. Returning to Cairo, Kleber faced chaotic rebellion.

In Egypt Generals Jacques Menou and Belliard Belliard capitulated by the end of 1801. Both generals and their men and the remaining members of the Scientific Commission were returned to France. The exceptional artist Vivant Denon became the first Director of the Louvre and founded its Egyptian Collection, and the savants spent the next few years compiling their research, artwork, and scientific analysis. For most of the soldiers, few would have agreed that this was the most pleasant time of their lives, especially those who suffered all their lives from the effects of wounds and disease contracted from the campaign. And yet, the achievements of the Institute were great and truly memorable—the savants’ work educated the entire Western world of the magnificent civilizations in the Land of the Nile.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments