By Vince Hawkins

Following the French Army’s brilliant victories at the twin battles of Jena and Auerstadt on October 14, 1806, the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte subsequently launched his Grande Armée in a devastating pursuit of the remnants of the Prussian Army. The end result was the disintegration of the Prussians as a viable fighting force and the occupation of their territory. On October 25, Marshal Nicholas Davout and his III Corps, the heroes of Auerstadt, were given the honor of leading the French Army into Berlin. On the 27th Napoleon received the keys to the city. Berlin, like Vienna, had fallen to the French.

A few days earlier, on his way to the capital, the Emperor had stopped in Potsdam to pay homage at the tomb of Frederick the Great, one of the few military commanders he admired. After viewing in silence the final resting place of the great king, Napoleon ordered confiscated as military trophies several of Frederick’s personal items, including his sword, general’s sash, and Ribbon of the Black Eagle. These, the Emperor stated, were “for the consolation of those of our invalides who escaped the catastrophe of Rossbach.” Thus the Seven Years’ War battle where France had been decisively defeated by Frederick’s Prussians had been avenged.

By November 6, one Prussian corps, that of General Lestocq, and a few fortresses and scattered detachments were all that remained of Prussia’s vaunted military power. Wrote historian David Chandler, “It had taken only 33 days to destroy the armies of Prussia and with them the legend of Prussian invincibility. The whole war had lasted only seven weeks. The blitzkrieg of Napoleonic warfare had once again been convincingly demonstrated.” Along with the capture of their major fortresses, tons of military supplies, hundreds of cannon, and the horses of 53 Prussian cavalry squadrons fell into French hands. These horses were a godsend, because the French squadrons were badly in need of remounts after the recent fighting. These fine animals would play a major role in the upcoming campaign.

Although he had destroyed Prussia’s ability to wage war and had occupied most of the country, Napoleon was vexed by the fact that the Prussians still refused to surrender. The Prussian king, Frederick Wilhelm III, had fled and was seeking the safety of his Russian allies who, despite Prussia’s present circumstances, had sworn to continue the war against France. Thus the defeat of Prussia had not brought France any closer to a general peace. The Emperor faced several other problems as well. Austria, part of the original coalition against France and now a declared neutral, was making plans to rearm. The discipline of the Grande Armée was starting to disintegrate and his soldiers were committing depredations against the Prussian people. A deputation from the Senate in Paris had come to Berlin, not to congratulate him on his recent victory, but to try to persuade the Emperor to make peace. England, the “nation of shopkeepers,” continued to finance hostile coalitions against France. Then there was Russia, the only enemy left against him who still had armies in the field.

Napoleon moved quickly to deal with the myriad problems facing him. He continued to try to bring Prussia to agree to a peace. He settled affairs with the Austrians by assuring them he had no hostile intentions against their territory and, by returning part of Silesia to their control, he guaranteed their continued neutrality. He coolly informed the Senate that he would make peace when Russia agreed to join with him in liberating Europe from English tyranny. As for England, on November 21 Napoleon issued the “Berlin Decrees,” which ordered the closure of all European ports under French control to English commerce and correspondence, and enjoined an economic blockade against Great Britain. The aim of the “Continental System,” as it came to be known, was to deny England access to European markets, thereby creating a state of economic ruin and social unrest among her people. If the English government were engaged in trying

to alleviate the pressure of a failing economy, it would have neither the time nor the money to finance any further coalitions against France.

Alexander Committed over 100,000 Soldiers to Aiding Prussia

As for Russia, Tsar Alexander I was not willing to accept French dominion over Europe. Besides, he still honored his military pact with Prussia. Realizing that the Russians would have to be dealt with sooner or later, Napoleon quickly decided on the former option. After allowing his troops a brief respite during which he formulated his battle plans, the Emperor launched six corps of the Grande Armée across the Oder River into Poland. His objective was to reach the west bank of the Vistula River where he would occupy a line from Thorn to Warsaw. If there were no major offensive movements from the Russians, the Grande Armée could safely winter in this region where it would be in a favorable position to renew the campaign the following spring. Such a maneuver would, he hoped, not only halt further Prussian attempts at mobilization in the region, but also excite the Polish provinces into open revolt. Although his six corps were widely scattered owing to their pursuit of various fleeing Prussian detachments, Napoleon nevertheless gave the order to cross the Oder and advance on the Vistula.

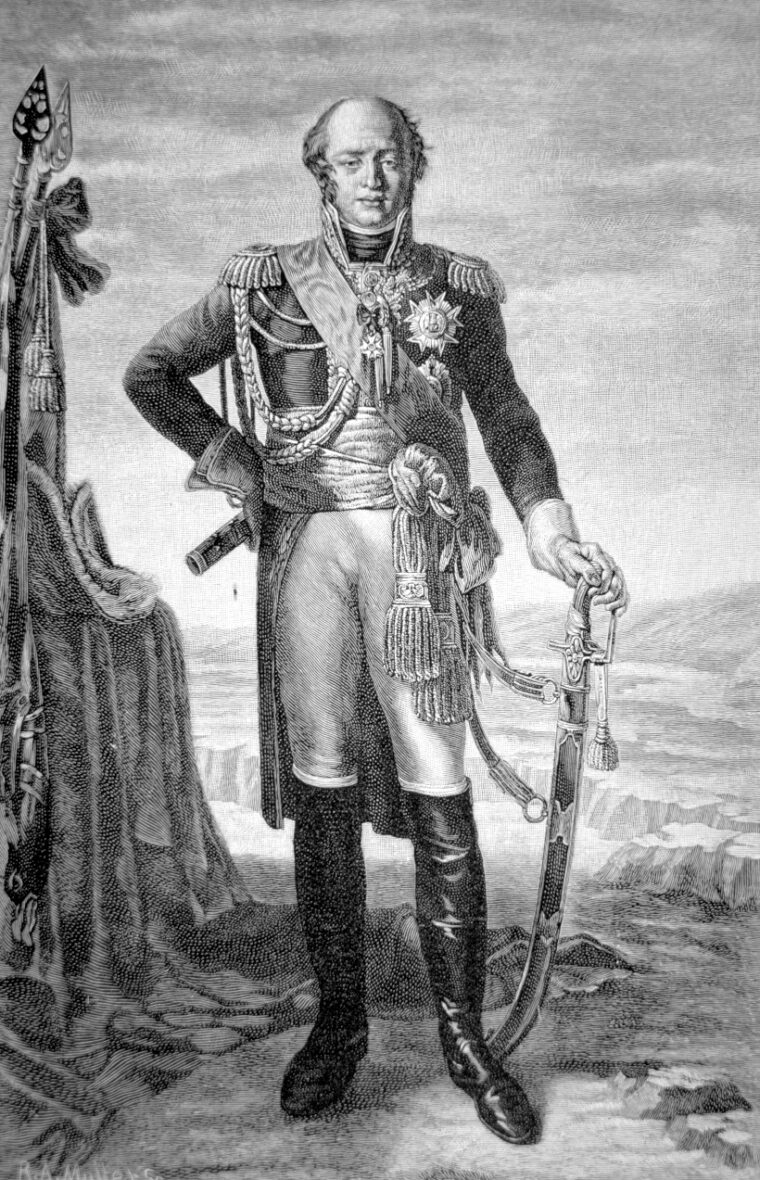

The Russians, under the orders of Tsar Alexander, had committed two field armies totaling some 105,000 men to support Prussia. The first of these armies, roughly 60,000 strong, was under the command of General Levin A.T. Bennigsen, a German in Russian service. The original plan was for the Prussians to await the arrival of the Russian forces before they engaged Napoleon. The Prussians, however, convinced of their martial superiority, attacked before the Russians could arrive to support them and were decisively defeated at Jena and Auerstadt. When Bennigsen learned of Prussia’s defeat, his army had only reached the town of Grodno on the Russian frontier in Poland. The news of the disaster at Jena, combined with his orders not to cross the Vistula, convinced Bennigsen that his best option was to withdraw and cover Warsaw in an effort to buy time for Field Marshal Friedrich Buxhowden to assemble his 45,000-man army near Koenigsberg and then effect a union of the two armies. This would also give Lestocq’s Prussian corps a chance to join with the Russian forces.

Upon learning of Bennigsen’s withdrawal from Warsaw, Napoleon correctly guessed that the Russian commander would attempt to take up a position between the Ukra and Narew Rivers, there to ultimately join with Buxhowden and Lestocq. He therefore ordered his army in pursuit with the objective of catching and defeating Bennigsen before he could unite with Lestocq’s Prussians or Buxhowden’s Russians. On December 15, Napoleon learned that Bennigsen and Buxhowden had united but were still continuing to retire from him. This maneuver resulted in two indecisive battles at Pultusk and Golymin on December 26. As a consequence of these actions, Napoleon called off his advance and the army retired into winter quarters.

The army would not stay long in winter quarters, however, because near the end of January 1807, Napoleon learned that Bennigsen had launched an unexpected attack against elements of two French corps. Napoleon discovered that, contrary to his orders, Marshal Michel Ney had moved his VI Corps forward through the Polish lakeland regions. Although Ney had made this move in an effort to find forage for his corps, the fact remained that Bennigsen viewed the VI Corps’ movement as a renewal of French operations against him. Napoleon was furious when he learned that the army’s wintering was being interrupted by a Russian offensive prompted by Ney. Over the next several days the dispatches sent to Ney from Marshal Louis-Alexandre Berthier, the chief of staff, were filled with the Emperor’s displeasure. Left with no other alternative, on January 27 Napoleon ordered out the army to deal with Bennigsen’s attack. “The Emperor does not wish to re-occupy his winter quarters before he has destroyed the enemy.” Despite the Emperor’s wishes there would be a winter campaign after all.

Bennigsen’s Amazing Stroke of Luck

Napoleon resolved to use Bennigsen’s advance against Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte’s I Corps as the bait for a trap. He ordered Bernadotte to fall back before the Russians, luring them westward. Meanwhile, the other four corps and the Imperial Guard would move to form a pocket around the “bait” with Ney’s corps linking the left of the pocket with the main body. The more Bennigsen advanced after Bernadotte, the deeper he would be in the trap. If the maneuver were successful the French would cut Bennigsen’s army in two and trap several of his corps in the pocket.

Napoleon, however, had misread Bennigsen’s original intention. While Ney’s movements may have prompted Bennigsen to move faster, the Russians had previously planned to launch an offensive and were already advancing when Ney moved his camp. Bennigsen, whose attention was fixed on Bernadotte, was moving blindly into the trap. Fortunately for the Russian commander, he was to be saved by a stroke of luck. A young, inexperienced French officer carrying a copy of Napoleon’s orders to Bernadotte got lost and was captured by Cossacks. Within a few hours an amazed Bennigsen was reading the Emperor’s detailed orders of the operation. Realizing the danger he was in, Bennigsen quickly ordered the army to concentrate at Ionkovo to meet this impending threat.

As reports of Russian withdrawals began to arrive at Imperial headquarters, Napoleon correctly surmised that Bennigsen was attempting to escape and had somehow learned of the French trap. Napoleon wrote, “Until this very moment the enemy has been hard pressed. It is now clear that he appreciates our maneuvers, though only with some difficulty, and wishes to escape—a fact that makes me think that he finds himself informé. Rumor in the countryside has it that he is everywhere retreating in an attempt to avoid the blow which is threatening him.” Napoleon then reckoned that Bennigsen would try to rally as many troops as possible and make a stand to hold up the French, thus allowing the rest of his army to escape the trap. He concluded that the enemy must be immediately attacked to prevent his escaping. The Emperor had correctly surmised the situation, but he did not realize that Bernadotte had never received his orders and was unaware of the French maneuvers.

On February 3 the Emperor, with elements of the Imperial Guard and five divisions from Ney’s III and Marshal Nicholas Soult’s IV Corps, arrived at Ionkovo. There he found the Russians drawn up in battle line waiting for them. Although having only limited forces at his disposal, Napoleon knew that the rest of Ney’s and Soult’s corps were close at hand, and that the Guard and Marshal Pierre François Augereau’s VII Corps were not far behind. He therefore resolved to attack at once. Giving command of Ney’s troops to Marshal Joachim Murat, he ordered him to pin the Russians in place while Marshal Soult tried to turn their flank and cut off their escape route. After a short but desperate battle, Soult’s troops managed to capture the bridge over the Alle River, which was on the Russian escape route. But because the Guard and Augereau’s corps did not arrive before nightfall, Napoleon was forced to wait until morning to finish off the enemy.

Fate Forces Napoleon’s Hand

The Russians were not done, however, and during the night they quietly marched out of the trap. The next morning revealed that the prey had flown and Napoleon once more set off in pursuit. On February 6 scouts brought word to Napoleon that Bennigsen had halted his withdrawal and taken up positions near the town of Eylau with 67,000 men and 460 guns. Although he had only about 49,000 men and 200 guns readily at hand, Napoleon knew that 14,500 men of Ney’s VI Corps, currently in pursuit of the Prussians, and 15,100 of Davout’s III Corps were within marching distance of Eylau, and would thus add another 29,600 men to his strength. Accordingly, Napoleon moved on Eylau, reaching the area on the afternoon of February 7, and arrayed his troops across the western ridges overlooking the town.

It was Napoleon’s intention not to begin the action until the remainder of the army arrived, but once again fate took a hand. The Imperial baggage trains, unaware of the Russian presence in Eylau, entered the town in search of quarters for the Emperor. Captain Jean de Marbot, an aide-de-camp on Augereau’s staff, recounts that “in the midst of their preparations they were attacked by an enemy patrol, and would have been captured but for the aid of the detachment of the Guard which always accompanied the Emperor’s outfit. At the sound of the firing the troops of Marshal Soult, who were posted at the gates of the town, ran up to the rescue of Napoleon’s baggage, and found the Russian troops already plundering it. The enemy generals, thinking that the French wished to take possession of Eylau, sent up reinforcements on their side, so that a bloody engagement took place in the streets of the town…. I know that some military writers on this campaign assert that the Emperor, not wishing to leave the town in possession of the Russians, gave orders to attack it. I am sure that this is a very great mistake, and I base my assertion on the following facts…. I heard Napoleon say to him [Augereau], ‘They wanted me to carry Eylau this evening, but I do not like night fighting; and besides, I do not wish to push my center too far forward before Davout has come up with the right wing and Ney with the left. I shall await them therefore till to-morrow on this high ground, which can be defended by artillery, and offers an excellent position for our infantry; and when Ney and Davout are in line we can march simultaneously on the enemy.’”

Both Sides Suffer Close to 4,000 Deaths

This incident quickly escalated into a full- fledged battle that raged on into the night and cost each side some 4,000 casualties. The result of this unplanned action was that the Russians withdrew, leaving the French in control of the town and its adjoining ridge. This at least gave the French troops some shelter from the cold winter weather, while the Russians were forced to bivouac in the open fields. The bleak, inhospitable terrain and the hostile, unyielding climate of Poland had already won the extreme hatred of the French soldiers, so much so that they had taken to complaining out loud and in full hearing of the Emperor. Napoleon thus began calling them les grognards, or “the grumblers.” At Eylau the terrain was to prove slightly favorable for the French, but the weather would remain a definite enemy to their endeavors.

Dawn of February 8, 1807, broke bitterly cold, the temperature at 2 degrees above zero with merciless, blinding blizzards that continually howled over the plains. Wrote Loraine Petre: “The whole surface of the country was wrapped in a white pall of deep snow, against the as yet unstained purity of which the black woods, villages, and the troops stood out in sharp relief. The undulations and the elevations, never very strongly delineated, were even less discernible than when color and shade were there to lend assistance to the eye. The lakes and streams were obliterated by the thick covering of snow, which lay on their frozen surface. So firmly were they locked in the grasp of frost, and so completely concealed by the snow, that troops of all arms, horses, wagons, guns, passed over their frozen surface, without the men being aware that water lay beneath their feet.”

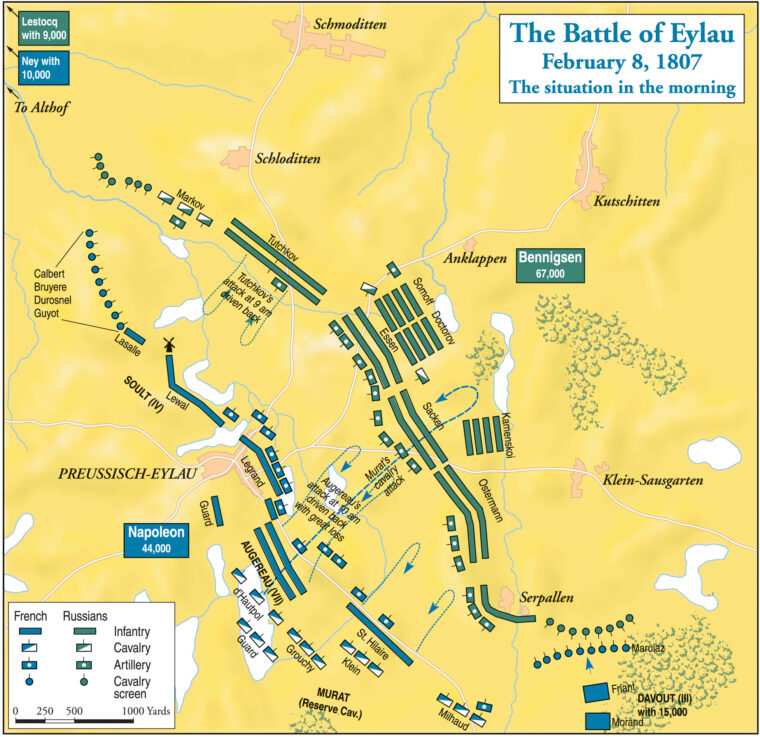

After pulling back from Eylau, Bennigsen deployed the seven divisions of his army (2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 7th, 8th, and 14th) in two great lines across his front. On his far right near the village of Schloditten he placed General Markov’s cavalry, with pickets of Cossacks extending northwest. These were to establish contact with Lestocq’s Prussians who were trying to shake off Ney’s pursuit and reach the field to support their allies. Next came the infantry of General Ivan Tutchkov commanding the right wing. In the center were the troops of Generals Jean Henri Essen and Alexander Kamenskoi under the command of General Dmitri Osten Sacken. On the left, extending past the village of Serpallen, were General (Count) Ivan Tolstoi’s troops, under Generals Ostermann and Bagavout. General André Gallitzen’s cavalry was massed on either flank and the infantry reserve under General Dmitri Sergeivich Doctorov was drawn up in two columns behind the center. Bennigsen also had massed several large batteries of artillery at various points on his line. Near Anklappen, Bennigsen’s headquarters, was a battery of 60 horse artillery guns. A battery of 70 guns was in front of Essen’s troops, facing Eylau; another of 60 guns was slightly in front of the main battle line on the right; and a third battery of 40 guns was poised between the center battery and Klein Sausgarten.

Napoleon Regarded the Russian Commanders as Sluggish and Unimaginative

The Emperor had arrayed his troops in a similar fashion. On the far left was General Antoine Lasalle’s cavalry, with pickets facing Markov’s Cossacks. Commanding the left was Soult with the IV Corps, two divisions of which, General Lewal’s and General Claude Alexandre Legrand’s, were positioned on either side of Eylau. Behind Legrand and to the right of the town was the Imperial Guard, held in reserve as always. Next came Augereau’s VII Corps and to his right General Louis St. Hilaire’s division of Soult’s corps. Behind Augereau and St. Hilaire and extending to the village of Rothenen on the right was the cavalry reserve commanded by Marshal Joachim Murat, and behind them the cavalry of the Guard under Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessières. On the far right was General Edouard Milhaud’s dragoons of the cavalry reserve.

Napoleon’s plan was a double envelopment by the corps of Ney and Davout while he held the Russians in place with a pinning attack against their front. By the time the action opened, however, Davout’s corps had not yet arrived and Ney’s corps was even farther behind schedule owing to the fact that Napoleon did not send him the orders to march to Eylau until 8 o’clock that morning. Even though he was some 29,000 men below his planned battle strength, Napoleon, trusting in the sluggish and unimaginative nature of the Russian commanders, believed he could hold the field until these reinforcements arrived.

The battle began around 8 am with a massive Russian artillery bombardment. As shot and shell fell in and around Eylau the French gunners responded. An artillery duel quickly ranged all along the line, the angry rumble of the guns muffled by the wind and falling snow. Although the Russians had the heavier weight of metal, they got worse than they gave owing to the superior quality of the French gunners and the fact that the French guns were of necessity more extended than those of the Russians. The French also had the benefit of some cover from the towns, while the Russians were massed together in the open and silhouetted against the snow. Within an hour both Eylau and Rothenen were burning, the smoke mixing with the snow and casting a dark pallor across the field.

Around 8:30 Napoleon ordered Soult’s corps, supported by Lasalle’s cavalry, to demonstrate against the Russian right, pinning them in place and distracting their attention from their left flank where he expected to make the main attack with Davout’s corps. Davout’s leading unit, General Louis Friant’s division, was just then approaching the field and would need time to deploy. This unenviable task had the immediate and opposite result desired. Instead of pinning the Russians in place, Soult’s advance goaded Tutchkov into launching a massive retaliatory attack that slammed into the IV Corps. By 9 am Soult had fallen back and was desperately trying to hold Windmill Hill against overwhelming pressure. At the same time, a large force of Gallitzin’s cavalry surged forward from the Russian left and fell on Friant’s columns as they began to deploy.

Napoleon had not counted on Soult being so badly mauled so quickly, nor on Davout having to force his way onto the field amid masses of cavalry. With both flanks thus threatened, Napoleon had two options: He could either pull back Soult and trade space for time in hopes that Davout and Ney could then arrive on the field in force, or he could ease the pressure on Davout by counterattacking the Russian left. Believing that Bennigsen would probably renew the attack against Soult and then drive for Eylau, Napoleon decided on the latter course and ordered Augereau’s VII Corps to create a diversion by advancing against the Russian left.

Heavy Snow and Winds All But Stopped Napoleon’s Soldiers From Advancing

Augereau, although very ill, put his corps in motion. Supported on their right by St. Hilaire’s division, which was to serve as flank security as well as link up with Davout’s left, the VII Corps surged forward through a renewing blizzard. “The snow prevented the commanders from seeing their troops, the howling north wind rendered it impossible for the soldiers to hear the word of command. At times, it was not possible to see ten yards off. The action at such moments had the character of a night attack,” wrote Petre. With the wind blowing in their faces and unable to adequately see through the swirling snow, the two units diverged. This resulted in the VII Corps swinging to its left, thus moving across the front of the Russian lines. One battalion, the 14th Regiment of the Line, had veered more to the right and suddenly found itself alone in front of the enemy’s position. In the darkness the French batteries in front of Eylau mistook Augereau’s men for the enemy and began to fire. As they continued groping their way to the left, the VII Corps moved straight toward the Russian center where lay the 70-gun battery. Noting the direction of the French columns, Bennigsen had moved forward units from his reserve to counter them. These troops now fired a volley at close range and then charged the staggered French with bayonets. At the same time Russian cavalry charged down upon the survivors. “No troops could withstand such an onslaught in front and on both flanks, especially when the Russian cavalry were in their midst before they were perceived through the snow. Almost every regiment was broken; the whole mass fled in the wildest confusion, followed, bayoneted, sabred by the victorious Russians,” wrote Petre. By 10:30 the VII Corps had lost some 5,200 men, almost 40 percent of its strength, and one of its generals had been killed and the other seriously wounded. Augereau was also wounded, having been hit by canister fire.

As the remnants of the VII Corps fell back to the cemetery at Eylau, St. Hilaire’s attack stalled. Facing massive fire to its front and cavalry charging its now-exposed left flank, St. Hilaire’s division recoiled. Bennigsen saw his chance and threw Doctorov’s reserve infantry in quick pursuit of the VII Corps. From the church in Eylau the Emperor had watched the destruction of Augereau and the repulse of St. Hilaire. Now he saw two dark columns of infantry, over 4,000 strong and supported by cavalry, moving rapidly toward the town. The Russians swept into Eylau, threatening to break the French center. One column advanced straight on the Emperor’s command post, putting his life in jeopardy. As the Russian infantry bore down on him, Napoleon’s escort, a squadron of Chasseurs of the Guard, rushed forward to his aid. With cries of “Vive l’Empereur!” they unflinchingly threw themselves in a suicidal charge against the head of the Russian column. Their sacrifice delayed the Russians long enough for two battalions of the Guard to arrive and restore the situation. In the meantime, Murat ordered a cavalry charge against the rear of the Russian column. Caught in front and rear the Russian column suffered the same fate as Augereau’s men and was slaughtered, the survivors fleeing back toward their lines.

“Are You Going to Let Those Fellows There Devour Us?”

The Russians were momentarily halted, but the threat to the French center remained critical. If Bennigsen pressed his attack, his weight in numbers could break the French left and center and roll up their entire line. According to some accounts, at this point Napoleon turned to Murat and said, “Are you going to let those fellows there devour us?” Other sources claim the Emperor ordered, “Take all your available cavalry and crush that column.” Whatever was said, Murat understood the meaning. Galloping away from Imperial Headquarters at around 11:30, “Murat began to ride across the front of the leading dragoon division, then suddenly wheeled his horse and galloped towards the Russian lines. The French cavalry spurred after him, 70 squadrons rolling in three waves over the snow,” wrote David Johnson. First came General Dahlmann with six squadrons of Guard Chasseurs, followed by Murat with the cavalry reserve and the dragoon divisions of Grouchy, Klein, and Milhaud. Joining on their right came d’Hautpol’s cuirassier division, and following the whole was Bessières and the cavalry of the Imperial Guard. As the Guard waited for its turn to advance, Colonel Lepic of the Horse Grenadiers noticed some of his men ducking from the Russian artillery fire that had begun to fall among them. Turning to his men Lepic shouted, “Heads up, by God! Those are bullets—not turds!” The honor of the Imperial Guard demanded it meet the enemy’s fire without flinching.

The relatively flat, snow-covered ground at Eylau afforded the French cavalry one of the finest fields of maneuver it had ever had, and Murat’s 10,700 troopers hit the Russians like a thunderbolt. They ran down the remnants of the Russian column repulsed from Eylau and then divided into two wings. One slammed into the flank of the Russian cavalry that had chased St. Hilaire’s division and rolled it back on the infantry, while the other hacked its way through the enemy infantry that had annihilated the 14th Regiment. Bennigsen sent forward his cavalry to meet the charge but Murat and his men forced them back, the heavier Prussian mounts and the impetus of the charge overwhelming the Russians. Yet still they went on, thundering down on Sacken’s infantry.

They broke through the first two lines and pierced the Russian center, eventually halting well in the enemy’s rear. As the Russians reformed behind them the Guard cavalry arrived and broke their lines a second time. Exhausted, their horses blown, the French cavalry was again surrounded by the infantry lines reforming behind them as well as by Cossacks swarming around them; it seemed like there was no escape. A Russian officer demanded Lepic’s surrender. Lepic pointed his sword toward his men and shouted, “Look at these faces! Do they look like men who would surrender?” The only way out was the way they had come. Murat reformed his cavalry into a single column and they charged again, cutting their way back through the enemy infantry to reach the safety of their own lines. It was a magnificent charge, one of the greatest in all military history, and for the loss of some 1,500 troopers, Murat had temporarily alleviated the danger and won for the Emperor a much needed respite.

Prussia to the Rescue?

It was then suggested that the Imperial Guard be committed to take advantage of the success gained by Murat’s cavalry, but the Emperor refused. The Guard was his only reserve, the only fresh troops remaining in case Bennigsen renewed the attack against his center. Besides, there was still the possibility that the Prussians might arrive on the field. So the opportunity passed and the Guard held their position. Bennigsen had also missed his opportunity to break the French lines, but now his attention turned from his center and Murat’s cavalry to his left and Davout’s corps.

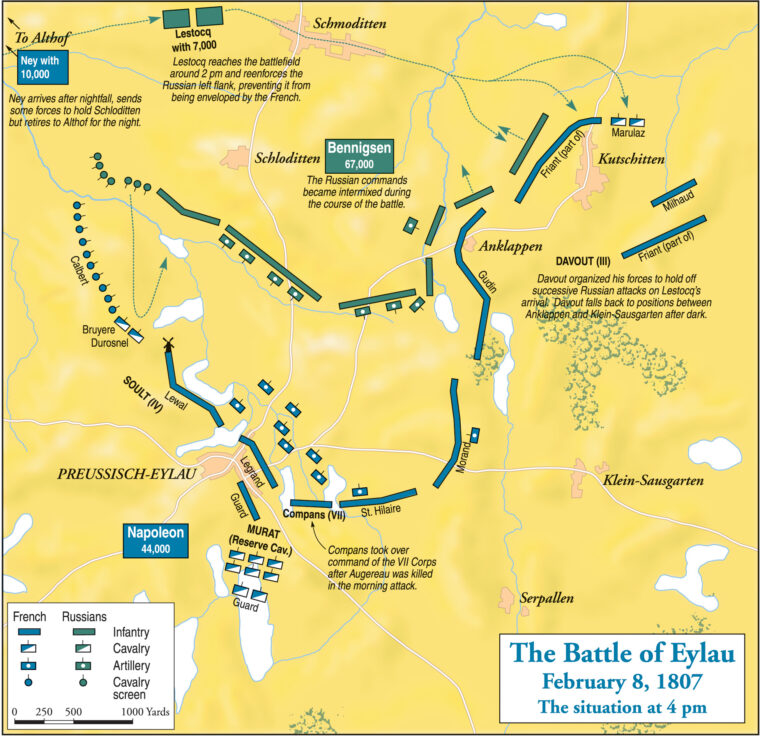

Around noon, with III Corps at last on the field and deployed for action, Napoleon ordered Davout to attack the Russian left. With St. Hilaire supporting his left flank and Friant’s division leading, Davout hit the Russian left hard, forcing it back at an angle to their main line. Friant took Serpallen and then drove toward Kutschitten in the Russian rear. After bitter fighting the French took Kutschitten and then pushed the Russians out of Anklappen, forcing Bennigsen and his staff to abandon their headquarters. The road through Kutschitten was Bennigsen’s main escape route, and when the village fell Russian morale plummeted. By 3:30 pm the entire Russian left flank was retreating before III Corps’ attack. Just when it looked as if Davout would secure a French victory, the Prussians arrived at Kutschitten.

Having eluded Ney, Lestocq’s weary corps arrived at Schloditten on the Russian right around 1 pm. Here he received an urgent message from Bennigsen ordering him to support the threatened left flank. After allowing his men a brief rest, Lestocq marched through Schloditten and passed behind the Russian rear, gathering whatever Russian troops he could along the way. At about 4 pm Lestocq’s 5,584 Prussians crashed into Davout’s open right flank near Kutschitten, rolling them back and driving them from the village.

Davout’s men fought fiercely to hold the ground they had won, but the Prussians slowly pushed them back. In Kutschitten the 51st Regiment of the Line and four companies of the 108th Regiment were annihilated. No quarter had been asked and none was given. The French continued to recoil before the Prussian onslaught, falling back on Klein Sausgarten. The Russians, their morale restored by Lestocq’s arrival, fell in on the Prussians’ right and returned to the battle, driving the French from Anklappen. Davout, seeing the danger he was in, concentrated his artillery on the heights near Klein Sausgarten and tried to rally his men. Riding among them he shouted, “Here the brave will find a glorious death; it is the cowards alone who will go to visit the deserts of Siberia!” Having rallied and reformed his men into line, and with supporting fire from his artillery, Davout finally halted the Prussian advance near Klein Sausgarten. Now the Emperor’s eyes turned toward Schloditten, where the sound of guns announced the VI Corps’ arrival on the battlefield.

“What a Massacre! And Without Result.”

Ney, heavily engaged in pursuing the Prussians, had not received Napoleon’s orders to come to Eylau until around 2 pm. Unable to hear the roar of the guns because of the constant blizzards, the marshal was unaware that a major battle was in progress. By sheer luck a corporal saw Ney and called to him, “Marshal, come and look. There’s the devil of a battle going on over yonder! Continuous gunfire!” Climbing to the top of a slope Ney saw for himself the flashing of gunfire and immediately turned his corps toward Eylau. At around 6 pm Ney was racing through Althof, his guns covering the advance. By 7 o’clock the VI Corps had deployed in battle order and was marching on Tutchkov’s right flank at Schloditten. Within the hour the village had fallen and the Russian right was turned. Tutchkov reformed his men, counterattacked, and by 10 pm the village was again in Russian hands. Ney, unable to discern much in the darkness, fell back slightly to a position covering Soult’s left and rear. By 11 pm the firing had ceased along the line and the battle mercifully came to an end.

Although it was not the coup de grâce that Napoleon desired, Ney’s arrival did convince Bennigsen that any hope of victory was now irretrievably gone. During the evening he withdrew his army, granting Napoleon the field and the victory, such as it was, and marched toward Friedland.

In reality, 14 hours of bitter fighting in horrendous weather conditions had only served to leave some 25,000 French and over 15,000 Russians and Prussians dead, dying, or wounded on the field. The two sides had essentially fought each other to a bloody standstill in what was little more than a drawn battle. The end result of this action was that Napoleon and his Grande Armée, for the first time in their illustrious careers, had received a major check on the battlefield. Napoleon retained the field owing in large part to Bennigsen’s failure to exploit his opportunities and utilize his superior numbers. In this case the Emperor, admittedly with the help of his subordinates, ignored his own proven rules of warfare and allowed himself to be drawn into fighting a battle for which he was not fully prepared.

This was the first substantial check in Napoleon’s military career, and in it much of Europe took heart. Ney rode the battlefield on the 9th. Discouraged, he uttered, “Quel massacre! Et sans resultat.” (“What a massacre! And without result.”)

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments