By Brandt Heatherington

Perhaps the most primal and profound fear of men and animals alike is the fear of fire. With that in mind, fire has been a mainstay of combat for thousands of years, from burning arrows to scalding cauldrons of oil. However, it was not until 1913 that a German inventor named Richard Fiedler would improve and refine pure flame as a controllable, efficient weapon, just in time to unleash a blazing hell on the battlefields of World War I—the likes of which no soldier in history had ever experienced. The basic concept of the flamethrower was to spread fire against an enemy position by launching a concentrated jet of burning fuel. The earliest flamethrowers date back as far as the 5th Century BC, in the form of long tubes filled with burning materials such as coal or sulfur, and were used in the same way that one would use a blowgun. The modern flamethrower had its genesis at the turn of the 20th Century. Two models, one larger and one smaller, were developed by Richard Fielder for the kaiser’s Imperial Army in 1901. It took another 12 years for Fielder to work out the technological issues and overcome objections from the German general staff, but eventually both models of flammenwerfer—German for “flamethrower”—were adopted for field use by three specially organized shock battalions.

The smaller, lighter flamethrower, the kleinflammenwerfer, or “small flamethrower,” was designed for portable use and could be carried by one man. Using pressurized air and either carbon dioxide or nitrogen as a catalyst, it shot a stream of burning oil as far 60 feet and had enough fuel for about two minutes of total firing time, though not consecutively. Each time the operator wanted to fire a new burst he had to replace the ignition device, a serious inconvenience that led to a limited lifespan for the kleinflammenwerfer. The larger model, the grossflammenwerfer, or “large flame thrower,” worked in a similar fashion but had a range nearly twice that of the smaller model. It could sustain a jet of flame for almost 40 seconds but had major drawbacks in that it used more fuel and thus cost more to operate. It was also so heavy that it could not be carried and operated by one man.

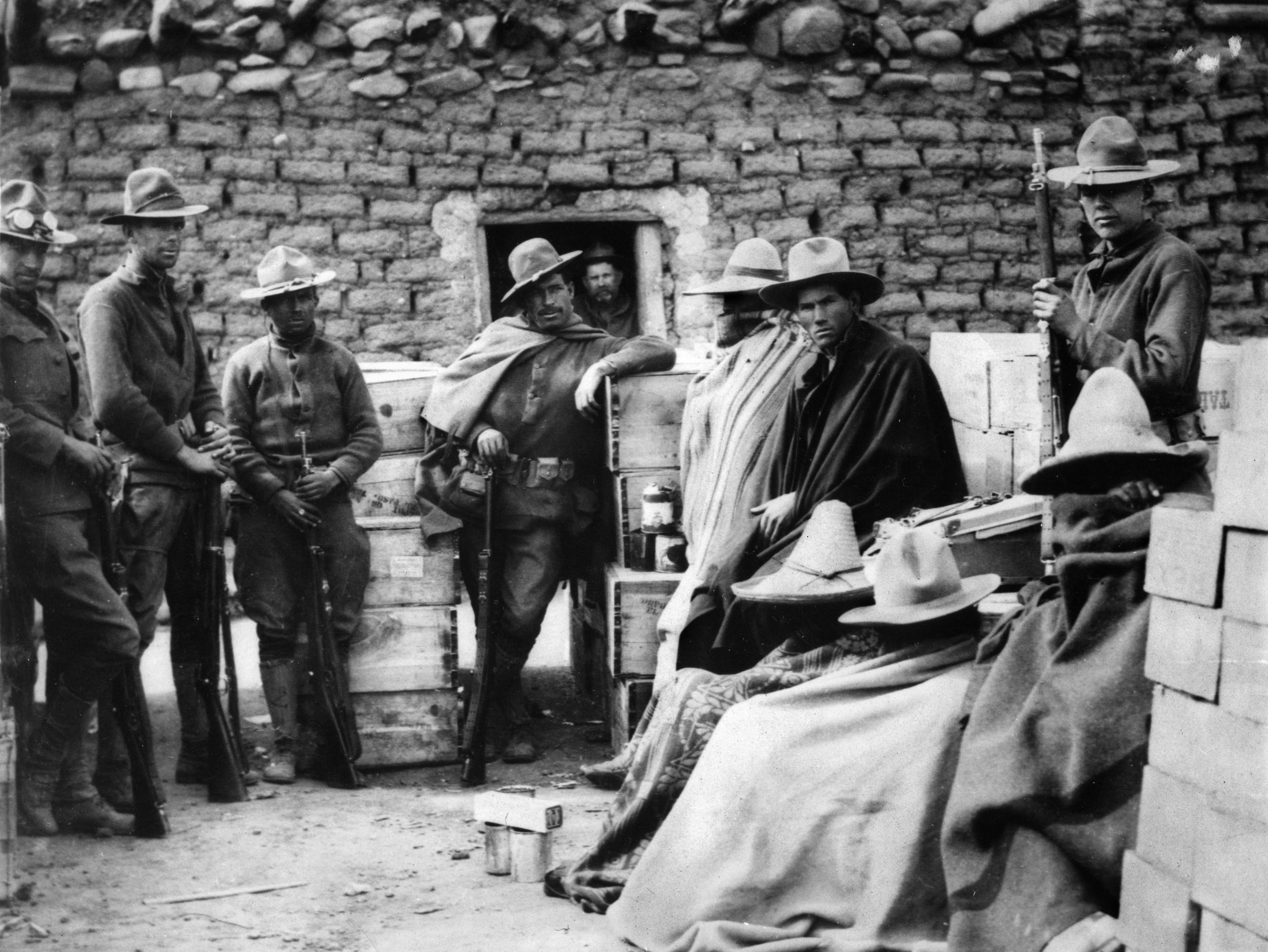

German Shock Troops Made Good Use of Flamethrowers

Despite the problems, both models came into service in the German Army during World War I. The effect of the new weapon was medieval in the reaction it provoked when first used against French troops in October 1914. (Read all about the Great War and its impact on the history of Europe inside the pages of Military Heritage magazine.) However, its use was sporadic, confined to an isolated part of the Western Front, and so went largely unreported. Soon the initial shock and mystery of this new “wonder weapon” passed, and the flamethrower—which had clearly crossed a new moral boundary—was rapidly adopted by Allied armies. This was par for the course, as World War I was particularly infamous for the ruthless way that each side matched the other’s increasing levels of brutality. The United States was a latecomer to the war, and never adopted a flamethrower of its own during the conflict. In fact, although not a particularly complicated weapon or difficult to manufacture, America did not develop its own flamethrower until 1940.

After its initial success, the flammenwerfer was next used in a surprise attack against entrenched British soldiers at the Hooge Crater, the area of an extended standoff during the Ypres Salient campaign in the Flanders region of Belgium. Springing from their positions shortly after 3 am on July 30, 1915, the German Stosstruppen, or “shock troops,” made effective use of the flammenwerfer, cutting an eerie silhouette in the darkness with portable gas tanks strapped to their backs and lit nozzles attached to each cylinder. The sudden attack with the bizarre new weapon proved extremely unnerving to the British, and their line was immediately pushed back. Eventually it stabilized later that same night, but after two days of heavy fighting the British lost 31 officers and 751 men in their first encounter with the flamethrower.

With the success of the Hooge attack, the German army adopted the flamethrower on a widespread basis on all fronts of battle. Flammenwerfers were used in groups of six, each apparatus serviced by two men. The main intent was to clear away forward defenders at the beginning of an attack, followed by an infantry assault. The operators of the Flammenwerfers themselves lived a most hazardous existence on several levels. Aside from the inherent dangers of handling the infant device—it was entirely possible that the cylinders carrying the fuel might unexpectedly explode at any moment—the flammenwerfer soldiers were marked men. The British and French poured rifle fire into the area of an attack where the flamethrowers were being used in the hopes of exploding their fuel tanks, and the operators could expect no mercy should they be taken prisoner by the frightened and enraged enemy. Accordingly, their life expectancy was extremely short.

The British, intrigued by the possibilities suggested by flamethrowers, experimented with their own models. In preparation for the 1916 Somme offensive, they constructed four gigantic models weighing almost two tons each, built directly into forward trenches constructed in no-man’s-land a scant 60 yards from the German lines. Each weapon was painstakingly assembled piece by piece, although two of the units were destroyed by enemy shellfire prior to the July 1 start of offensive. The remaining two, each with a range of approximately 90 yards, were put to use as planned. Highly effective at clearing trenches on a local level, they were of little or no other benefit, and consequently were abandoned.

Mobility would prove to be a decisive factor in determining the future service of the flamethrower. The French developed a portable one-man unit of their own called the schilt, of a superior design to the German model, which was used in trench attacks during 1917 and 1918. The Germans subsequently produced a lighter weight version of the flammenwerfer in 1917 known as the wex, which had the added benefit of being self-igniting with a reusable striker. In all, the Germans launched some 650 flamethrower attacks during World War I; no numbers are available for the French and British.

Flamethrowers Inflicted Sever Psychological Intimidation

The weapon’s appeal and deadly practicality were undeniable, especially at close range. Flamethrowers, it was soon discovered, could be used to bounce a jet of flame off the walls or through windows and doorways of buildings and fortifications, and thus could be used against an enemy even when he was not in direct line of sight. In many cases, even when the flames did not reach their intended targets, they consumed so much oxygen in a confined space that enemy soldiers suffocated—debatably a more humane though less immediate death than being incinerated. A jet of fuel could also be sprayed into a designated area and ignited from a safer distance with another burst, a technique that would come to be known as the “wet shot,” which produced an immense fireball. With its mobility increased, the flamethrower’s lethality on the battlefield became even more fearsome. By the close of the war, its use had been extended to mounting on tanks, an innovation that carried forward to World War II. The flamethrower had come into its own as a unique weapon that could be used in a multitude of capacities—destroying enemy emplacements, clearing vast areas and denying ground, and, most importantly, inflicting severe psychological intimidation on its intended victims.

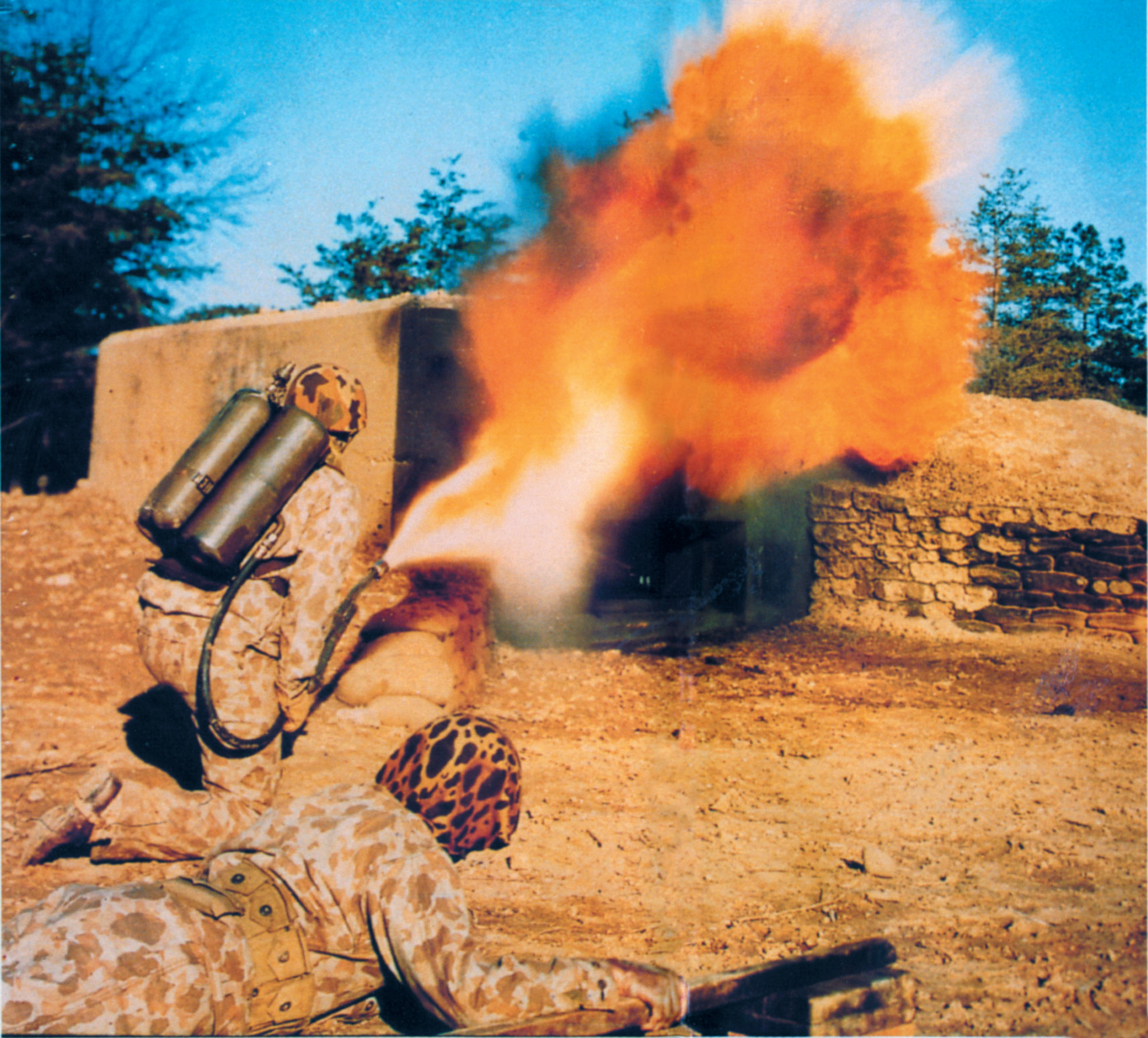

By far the most widely used flamethrower on any side during World War II was the U.S. M2-2 model, preceded by the M1A1, which came into service in 1942. Both models were issued to the Army and Marine Corps, and the United States built nearly 25,000 of these units during the war. Used on both fronts, the M1 and M2 were probably best remembered in photographs of the grisly results they produced in clearing Japanese from their bunkers on Pacific islands. On Iwo Jima alone, some 485 flamethrowers came ashore on the backs of soldiers or mounted on tanks. They saw limited use in the European theater, as combat moved too rapidly for the Germans to construct enough fortifications to require the use of flamethrowers to clear.

The American-made M2, like its World War I predecessors, required a team of men to operate and used diesel fuel, regular gasoline, or gel gasoline, later known as napalm. The weapon consisted of two main components: the tank group and the gun group. The tank group weighed almost 30 pounds and included two fuel tanks, a compressed air tank, a pressure regulator, and two safety heads. The gun group weighed six pounds and consisted of the flamethrower gun, a fuel hose, and two triggers one to turn on the flow of juice and one to ignite the stream utilizing one of five supplied igniter cartridges. The whole unit weighed 35 pounds empty and 62 pounds when it was filled with fuel and propellant. The entire contraption was attached to pack frame with a quick-release strap in the event the operator had to ditch the unit in a hurry.

To fire the flamethrower, a soldier would turn on the pressure regulator, which in turn pushed compressed air into the fuel tanks and moved the fuel into the gun group. The safety trigger in the rear was then pulled, moving the fuel from the tank into the hose, and squeezing the front trigger ignited the match cartridge and subsequently the fuel stream. The U.S. model flamethrower carried about four gallons of fuel, or enough for about 70 seconds of flame if used in short bursts, as American soldiers were trained to do. Unfortunately, safety had not improved much by World War II, and all it took was one well-placed round or stray piece of shrapnel in the tank to doom the flamethrower operator to the same gruesome fate as his targets. Complicating matters was the unreliable ignition system of most American models, requiring the operator frequently to use his personal Zippo cigarette lighter to fire up the weapon.

The Germans, as with most of their technology, were constantly evolving the flamethrower throughout World War II, employing no fewer than 10 different models—both static and portable, man-carried and vehicle-mounted. They were very similar to American models, with the exception of using compressed nitrogen to propel the fuel instead of compressed air. One unusual model used blank 9mm pistol cartridges as its ignition system. For some reason, the flamethrower fell out of favor with the Germans after its use in the invasion of France during the early stages of the war. It did continue to be used in reprisal operations throughout the remainder of the war, particularly as a part of the Nazis’ “scorched earth” policies during their withdrawal from Russia in 1944.

Flamethrowers Remain in Many Modern Military Arsenals

Less recognizable designs from World War II included the British “Ack Pack,” a doughnut-shaped fuel tank with a small spherical pressurized gas tank in the middle. As a result of its appearance, British troops nicknamed it “the life buoy.” Russian Army flamethrowers had three backpack-mounted tanks sitting side by side. Some descriptions seem to indicate that the user could fire only three shots, each emptying one of the tanks in turn.

The M2 series of flamethrowers saw action again in the Korean War, but eventually it was superceded by the M9A1 in 1956. The lighter-weight M9A1 was similar to the M2 but had a redesigned squeeze trigger to replace the forward pistol grip and a holster for the flame gun mounted on a harness. The flamethrower continued to be used in Vietnam, where Viet Cong tunnels created the same tactical problems that Japanese caves and bunkers had posed in World War II. The flamethrower was also effective in offensive operations against Vietnamese villages and buildings, which were largely made of dried materials. The M9A1 flamethrower was eventually replaced in U.S. service in 1974 by a wholly new technology, the M202A1 incendiary rocket launcher. This weapon allowed greater range and protection for its user, better accuracy, and more effectiveness against vehicles, which conventional flamethrowers could not attack except in the rarest of circumstances, since it required the operator to get uncomfortably close to a mobile target.

As the mobility of infantry increased, and with it the development of more effective ordnance for destroying fortifications, the use of the flamethrower waned significantly after its heyday in World War I and the Pacific campaigns of World War II. Flamethrowers still remain in the arsenals of many armies today, however, and will never be entirely replaced as one of the most notorious terror weapons in the annals of modern combat.

My father, Dr Gordon M. Kibler(Major US Army) developed the later model of the flamethrower when he was a member of the US Army’s chemical warfare division during WWII

where are the real military flamethrowers of ww 2 ww1 and the bazookas are now in 2022.