By Joesph Horodyski

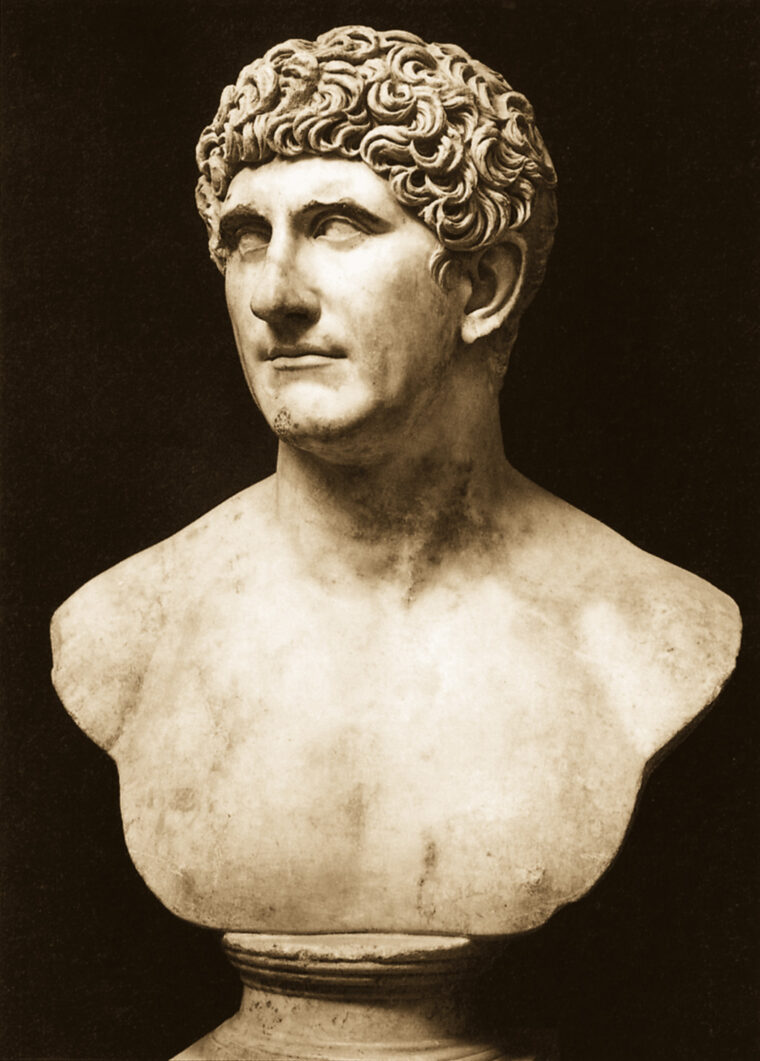

Julius Caesar’s assassination on the ides of March, 44 bc left Rome without a clear and decisive leader. Having just endured a brutal civil war that ended with Caesar’s ascension to dictator, the empire seemed headed for yet another period of internal turmoil. Caesar’s right-hand man and loyal lieutenant Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony), 39, quickly moved to take over Caesar’s mantle, and with it the leadership of many of the dead emperor’s military legions. As the individual chiefly responsible for hunting down and punishing those involved in Caesar’s murder, Antony proved himself relentless in the pursuit. Besides bringing justice to Caesar’s killers, it was a convenient way of removing possible rivals for power.

One rival, however, was beyond the immediate reach of Antony’s vengeance. Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (Octavian), the adopted 18-year-old son of the late emperor, was named in Caesar’s will as his legal heir. Widely considered weak, timid, vacillating, and inexperienced, Octavian was actually a cunning and shrewd judge of character. He was determined to inherit his father’s position and all the power associated with it. Notified of Caesar’s death while in the Roman city of Brundisium, Octavian moved immediately to identify himself with his father’s image and thus lend any subsequent actions at least a veneer of legitimacy. He took the name “Caesar” as his own, a practice by which all subsequent emperors were also to be known. The very name had a tremendous emotional pull and meaning for the masses, and the boy underwent his first major transformation—from unknown teenager to newly crowned Caesar. Many of the troops present at Brundisium joined his cause, and as he embarked for Rome to claim the throne, his retinue began to grow in size, swelled by many veterans of Caesar’s campaigns who had resettled in the Italian colonies. By mid-April, less than a month after Caesar’s assassination, Octavian was nearing the outskirts of Rome.

Octavian and Antony on a Collision Course

Antony at first paid little attention to the threat. He dispatched no official deputations to meet the new Caesar and gauge his intentions. Preoccupied with securing the original Caesar’s powerful provinces for himself, Antony dismissed the youth’s arrival as having little relevance to the overall course of Roman politics. When Octavian finally entered Rome in late April, Antony unwisely continued to ignore him. Octavian kept his temper in check and arranged a meeting. When he showed up for his audience with Antony in the gardens of Pompey on the Oppian Hill, Octavian was pointedly kept waiting. The ensuing meeting did not go well, and the two parted on shaky terms. Antony subsequently moved to block Octavian’s adoption from being officially recognized and to prevent him from holding public office. Octavian, meanwhile, curried favor with the masses, and tensions between the two men quickly rose. Despite occasional public reconciliations, it was obvious to everyone in Rome that the two men were on a collision course.

Both men jockeyed for position and advantage. Antony openly accused Octavian of plotting against him, while the youth attempted, through his own agents, to undermine the loyalty of the army that Antony was bringing to Italy from Macedonia. While Antony was in Brundisium attempting to secure the loyalty of the army there, Octavian showed his daring once again. Despite the risk of being branded a public enemy, he toured Caesar’s old colonies of Campania and raised a private army of perhaps 10,000 men from among Caesar’s veterans. It was a powerful demonstration of the political magic that the name Caesar possessed and the intense personal loyalty it still commanded.

Octavian Assumes Command

Antony returned to Rome intending to denounce Octavian to the Senate when news reached him that two of his five legions in Macedonia had defected to Octavian. Fearing the worst, he took the remainder of his force and hastened to restore the situation. Open warfare threatened to break out between the two factions. The great politician and orator Cicero, in the last official act of his career, openly identified Antony as the greater threat to Roman freedom and began to champion Octavian’s cause. As a result, on January 1, 43 BC, Octavian’s illegal assumption of command was essentially legitimized with a grant of praetorian power from the Senate.

After gaining the Senate’s support and not wishing, perhaps, to plunge Rome into yet another civil war, Octavian began seeking a reconciliation with Antony, even to the point of securing the repeal of Senatorial decrees declaring Antony a public enemy of Rome. In November 43 BC, Octavian met with his rival on an island in a river near Bononia. Two days of difficult negotiations produced an agreement whereby Antony and Octavian, together with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, a well respected yet elderly general and occasional supporter of Antony’s, would form a Triumvirate of consuls (or Caesarians) that would run the nation for a period of five years, until December 31, 38 BC. The three men agreed to divide the westernmost provinces of the empire among themselves, with Octavian being allocated the seemingly minor provinces of Sardinia, Sicily, and North Africa, while Antony retained Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Judea, and Asia Minor, and Lepidus received Spain and Gaul. This Second Triumvirate, as it was known, in effect formed a military junta whose decisions were henceforth to be made without reference to the wishes of the Senate or any other political organ of the state.

The awkward and hastily decided “rule by committee” soon turned into something of a disaster. Individually, Octavian and Antony continued attempting to persuade influential senators and generals to join their respective sides. They united long enough to put down an armed rebellion in the east that was led by Julius Caesar’s chief assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. At the two battles of Philippi, Macedonia, in October, 42 BC, the Triumvirate bested the assassins, each of whom took his own life to avoid being captured. Eventually, Lepidus grew restive and attempted to seize Sicily by force. His troops mutinied and he was forcibly retired by Octavian, spending the remaining 23 years of his life in luxurious captivity in Rome. This essentially left the younger man in complete control of all the western provinces, while Antony controlled those in the east. In an attempt to bind the two competing parties together by marriage, Antony divorced his first wife, Fulvia, and married Octavian’s sister, Octavia. An uneasy truce continued, with an agreement between the new brothers-in-law to extend their partnership for another five years.

Returning to Egypt

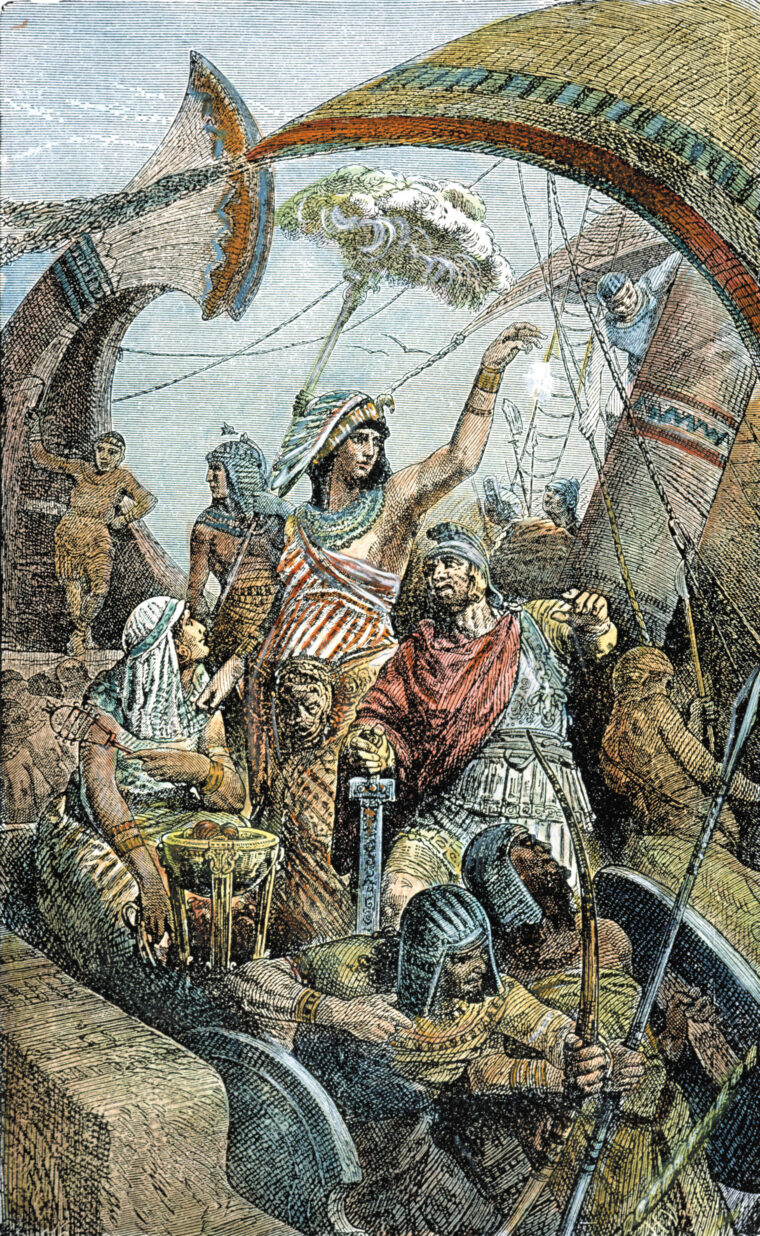

After helping to put down Lepidus’s rebellion, Antony returned to Egypt and began living openly with the queen of Egypt, Cleopatra, daughter of Ptolemy XI. Cleopatra, now 30, had years before managed to seduce Julius Caesar into an uneasy alliance that spared her country from the brunt of Roman occupation and brought Caesar an illegitimate son, Caesarion, whom many in Rome saw as a threat to the legitimate line of succession. Antony swiftly fell prey to the charms of Egyptian life and married Cleopatra, while neglecting to divorce Octavia, his Roman wife, whose marriage was not actually dissolved until 35 BC. This act was greatly resented by Roman citizens and helped to erode much of Antony’s remaining support among the masses and in the Senate, which now feared that Antony would put Caesar’s bastard son on the throne under his regency and make Cleopatra empress of Rome.

Octavian capitalized on the unsettled situation by releasing the contents of Antony’s supposed last will and testament, which left much of his land and wealth to Cleopatra and her children. The alleged document—probably a forgery—recognized Caesarion as Caesar’s true son and heir, which was a public affront to Octavian, who naturally disputed the child’s paternity. Cleopatra’s six-year-old son with Antony was proclaimed king of Armenia, Media, and Parthia, while their two-year-old son was bequeathed a vast kingdom in the Middle East that comprised Syria and all of Asia Minor west of the Euphrates River. Cleopatra herself was declared “Queen of Kings,” a vague title that suggested sovereignty over other monarchs outside of Egypt. More troubling to Roman sensibilities were reports that Antony himself appeared to have “gone native,” wearing eastern-style dress and practicing heathen customs and religion. It was even said that he had declared himself and Cleopatra the Greek god and goddess Dionysus and Aphrodite. From a Roman perspective, it seemed obvious that Antony was fully under the spell of Cleopatra and her charms.

The Triumvirate’s second term expired on the last day of December, 33 bc,leaving Octavian’s legal position somewhat delicate. At this point he ceased using the title “Triumvir,” while Antony quite pointedly did not. More incriminating documents mysteriously turned up purporting to show Antony seeking to extend his dominions in the east. Octavian wanted these papers made public to discredit Antony and immediately summoned the Senate to meet, although with the expiration of the Triumvirate he had no official power to do so. Octavian entered the Senate with a full military escort and openly denounced Antony. No one dared to raise a voice against him. Many pro-Antony senators, fearing for their lives, fled to the east. Clearly, Octavian was now all-powerful in Rome.

News soon reached the capital that Antony was forming his own Senate in Alexandria from among the exiled senators and that he had officially renounced Octavia as his wife and declared that he wished to be buried in Alexandria, next to Cleopatra. It seemed to many observers that Antony was indeed planning to establish a renegade eastern empire with a foreign queen as its head of state. Rumors swirled that the couple intended to move the capital of the empire from Rome to Alexandria. With cunning subtlety, Octavian managed to persuade the remnants of the Senate to declare war on Cleopatra—not Antony. Italy and the other western provinces, in a carefully orchestrated piece of political theater, then swore an oath of allegiance to Octavian. Although not legally binding, the oath served as a rallying cry for the populace and helped disguise the fact that Octavian’s power derived primarily from his control of the military.

Surprisingly, at this point Antony was not declared a public enemy, although he was stripped of all his offices for the coming year. Such a blanket declaration would have meant an overt war against Antony, something Octavian wished to avoid for the moment, instead choosing to portray the matter as one involving only the foreign interloper Cleopatra. In this way, Octavian sought to placate those supporters of Antony who already had defected to him and to reconcile any of Antony’s other supporters who might wish to join him later. But any way one wished to slice it, it was clear to everyone that a war with Cleopatra would also mean a war with Antony.

The war promised to be the largest civil conflict ever endured by the Romans. Arrayed against one another were the vast resources of the entire Roman Empire, west against east. After studying the situation, Antony planned to gather his forces in Greece, as far from his Egyptian seat of power as possible, to oppose Octavian’s advance eastward. He chose as his base the town of Patrae, on the southern coast of the Gulf of Corinth. When he learned that Octavian’s fleet was threatening a small detachment of his own ships in the Gulf of Ambracia in northwestern Greece, Antony hurried there with his entire force, including Cleopatra’s sizable flotilla, to increase the odds in his favor. Upon arrival he found himself in an untenable position, for while Antony’s land forces were more than the equal of Octavian’s, he had no experience in naval matters and indeed was now cut off from his main lines of communication by Octavian’s superior naval forces. While Octavian refused to fight Antony on land, Antony was, for the moment at least, unwilling to fight him at sea. An uneasy stalemate ensued.

Antony immediately set up a row of wooden towers on land and ships in the water to guard the entrance to the gulf. Octavian made his camp on the northernmost shore of the gulf across from the promontory at Actium. A few minor naval skirmishes ensued up and down the Greek coast, the most decisive being one in which Octavian’s chief admiral, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, managed to sever Antony’s lines of communication farther down the coast. Unwittingly, Antony’s fleet had let itself be trapped within the gulf with no open line of retreat. With the enemy bottled up this way, Octavian’s fleet could afford to sit and wait for events to work themselves out.

As the summer months passed, Antony’s forces began to deteriorate steadily. His army was slowly weakened by malaria, the result of his troops being stationed in a marshy, mosquito-infested lowland. Even worse, some of his closest supporters began going over to Octavian’s side, often on the pretext of their distrust of Cleopatra and her Egyptian forces. They complained that her continued presence constituted a bad omen that demoralized their men. Antony’s generals argued that as long as she was present, Cleopatra would serve as fuel for Octavian’s well-oiled propaganda machine. If she were to return home to Egypt, many in the Roman Senate, the army, and the masses would quit their support of Octavian. His generals pressured Antony into a land campaign against Octavian, while Cleopatra insisted that Antony held the advantage on the water and should attack by sea. The Egyptian queen clearly feared losing control over Antony if she was not present and so refused to leave his side. By late summer, only three senators remained with Antony, and as August turned into September it became obvious that something drastic had to be done before Antony’s entire force melted away.

Unable to decide between the two courses of action open to him, Antony unwisely chose both. He opted to take his lover’s advice and meet Octavian in a naval engagement to break the deadlock before his forces were depleted any further. He also decided to send Cleopatra home. But knowing that her fleet of 60 ships would return with her, and in dire need of every available vessel, Antony made the mistake of deciding to retain her services until after the coming battle had been fought.

Antony prepared for the coming battle byburning all his ships that were in poor condition and unlikely to be seaworthy in a military action. He then distributed the healthiest of the crews among his remaining ships, hoping to increase their combat effectiveness. Whether or not they would have been able to hold their own in an equal contest would never be known—on the night before the battle one of Antony’s key generals, Delius, defected to Octavian’s camp and brought with him Antony’s entire plan of attack. Octavian had originally intended to let Antony’s fleet slip by, hoping to fall upon its rear, but Agrippa feared that they would be too slow to catch Antony’s ships, especially if the weather were to worsen in Antony’s favor. Octavian relented and ordered his own fleet out into the gulf.

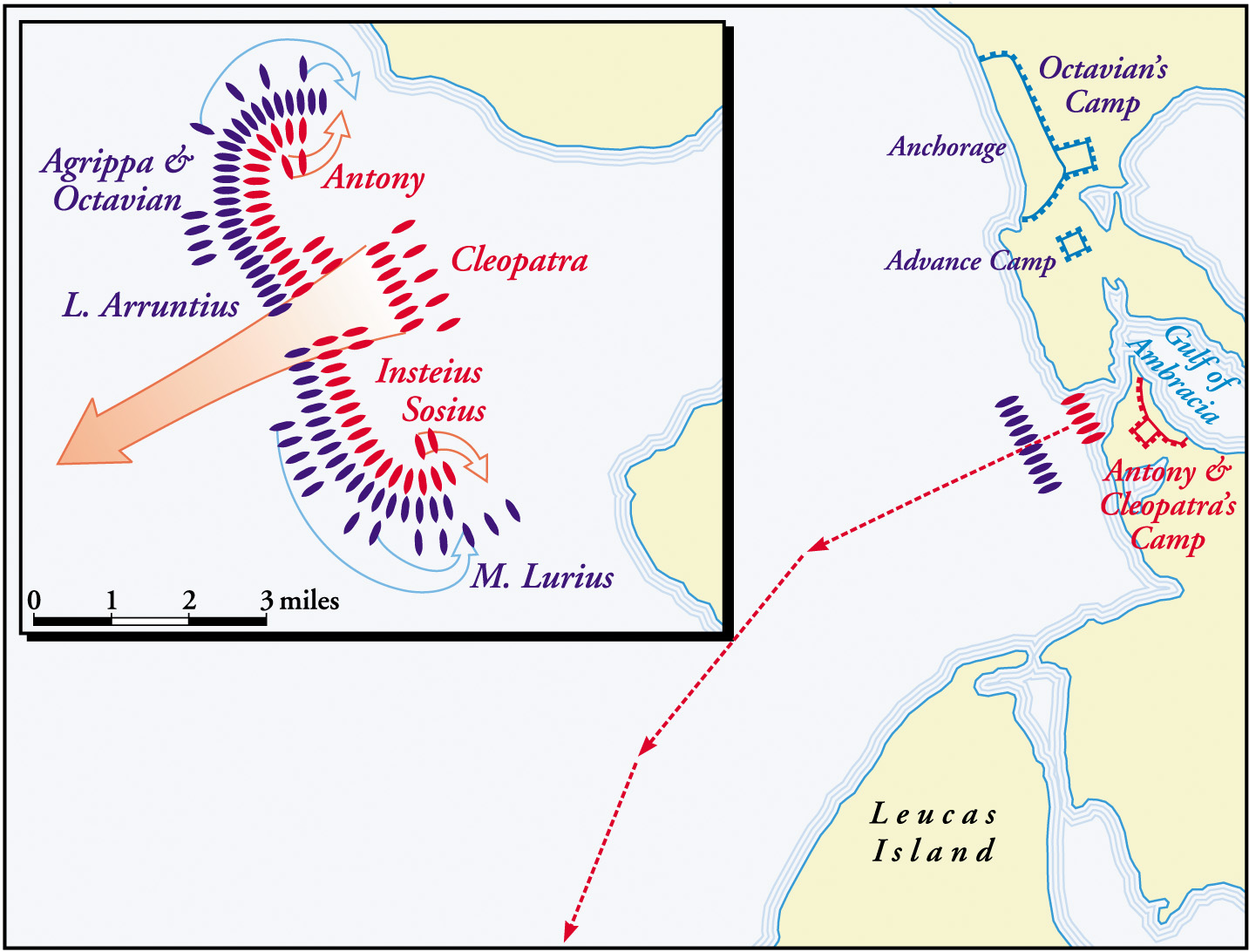

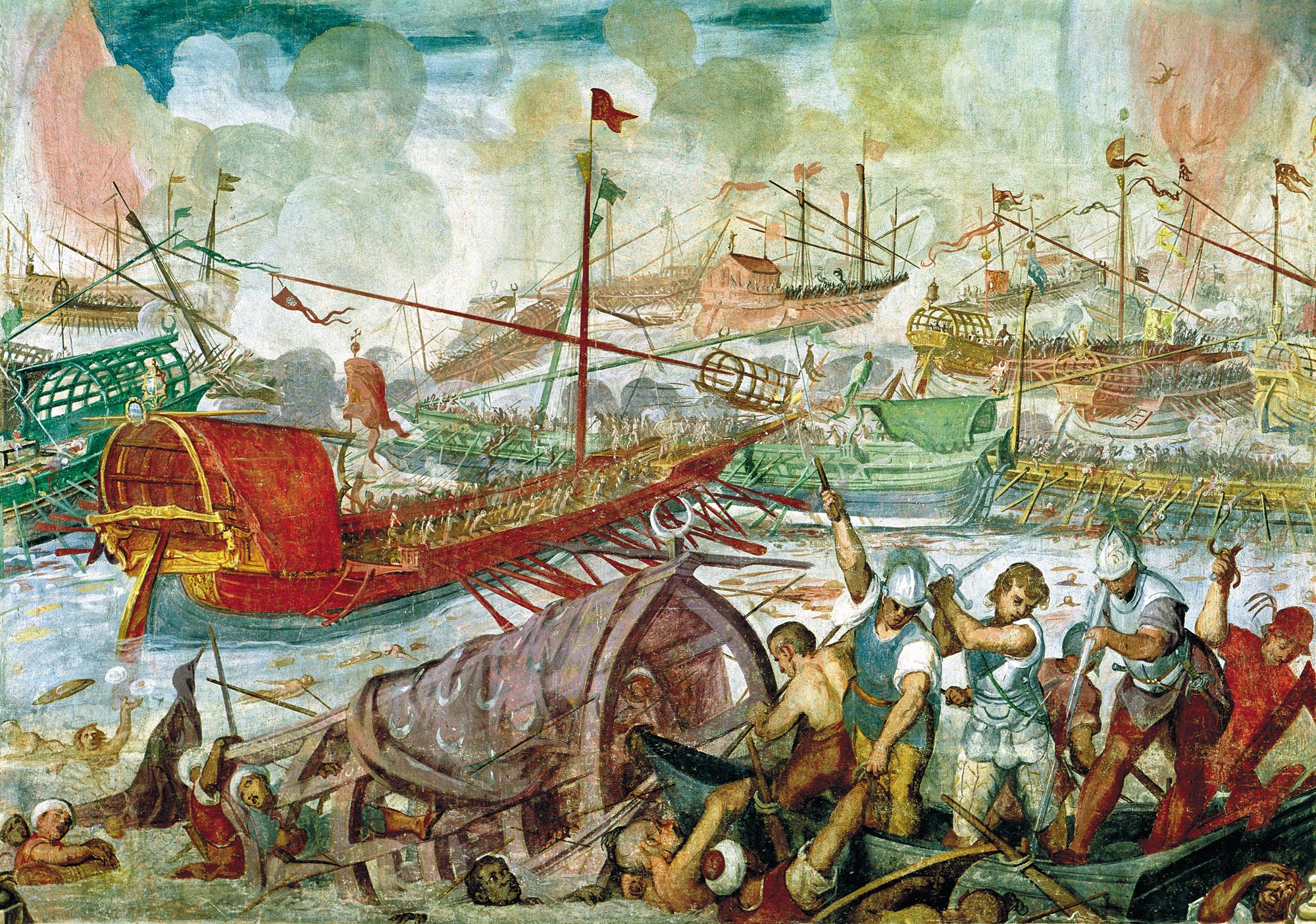

On the morning of September 2, 31 bc, Antony led 230 warships through the straits of Actium toward the open sea to meet Octavian’s fleet of 400 ships. Agrippa was waiting. He had arranged his forces in an arc from north to south to block any exit from the bay. Antony’s fleet consisted primarily of massive quinqueremes, huge galleys whose bows were armored with bronze plates and square-cut timbers, making them nearly impossible to ram. The quinqueremes featured their own gigantic bronze rams, some of which weighed upward of three tons. The ships were 200 feet long and carried 400 rowers and a substantial number of soldiers to man the catapult towers and toss spears and stones at the opposing sailors.

Octavian’s fleet consisted chiefly of smaller Liburnian vessels, armed with better trained and fresher crews. His ships were lighter, more maneuverable, and better able to protect themselves in a typical Roman naval battle, in which the object was to ram an enemy’s ship and sink it with a powerful, head-on collision, while killing the above-deck crews with a shower of arrows and catapult-launched stones large enough to decapitate a man. Since Antony’s ships couldn’t maneuver quickly enough to ram Octavian’s smaller, faster ships, and since Octavian’s lighter vessels couldn’t do much damage to Antony’s massive bronze-plated ships, the battle evolved more into a standard land battle than a classic naval engagement.

At 10 am, Antony’s fleet sailed into the open bay with his largest ships in the lead. He originally kept his forces tightly clustered together, seemingly intent on driving back Agrippa’s northern wing, but Octavian’s forces skillfully withdrew out of range, keeping a respectful distance between his ships and the massive prows of Antony’s fleet. Cleopatra’s 60 ships were held in reserve behind Antony’s right flank. By noon, Antony was forced to extend his line farther into the bay and away from the protection of the shore in an effort to bring the enemy to battle. Octavian simply retreated out of range, successfully luring the enemy fleet out into the open sea. Antony had taken the bait.

For more than two hours, Antony’s ships gave chase, the crews manning the oars at a steady beat of 35 strokes per minute and growing more weary with every passing mile. Soon exhaustion and dehydration began setting in, and men started dropping from their seats. As Antony’s fleet advanced, his tightly bunched formation began to lose cohesion, with ever-widening gaps beginning to appear between his ships as they fanned out to engage Octavian’s retreating vessels. When he sensed that Antony’s fleet was beginning to flag and move more sluggishly, Octavian’s ships reversed course and finally engaged Antony’s exhausted crews. Both wings of Octavian’s battle lines now bent forward in the shape of a long crescent, hoping to surround and outflank their rivals. Antony had no choice but to meet Octavian’s advance as best he could and do battle on Octavian’s own increasingly unpromising terms.

The center of Antony’s formation was in a state of confusion. When the two opposing sides came together, the air was torn by catapult fire, spears, and volleys of arrows as soldiers on both sides prepared to board and grapple with their enemies. Typically, two or three of Octavian’s smaller ships would engage a single one of Antony’s more cumbersome quinqueremes; as soon as it was put out of action, the Liburnians would move on to the next. As the afternoon wore on, the battle degenerated into a clash of opposing land tactics without much tangible gain by either side. Eventually, through sheer attrition, Octavian’s numerical advantage began to tell, as more and more of Antony’s ships were surrounded and put out of action. Antony’s plan had clearly failed.

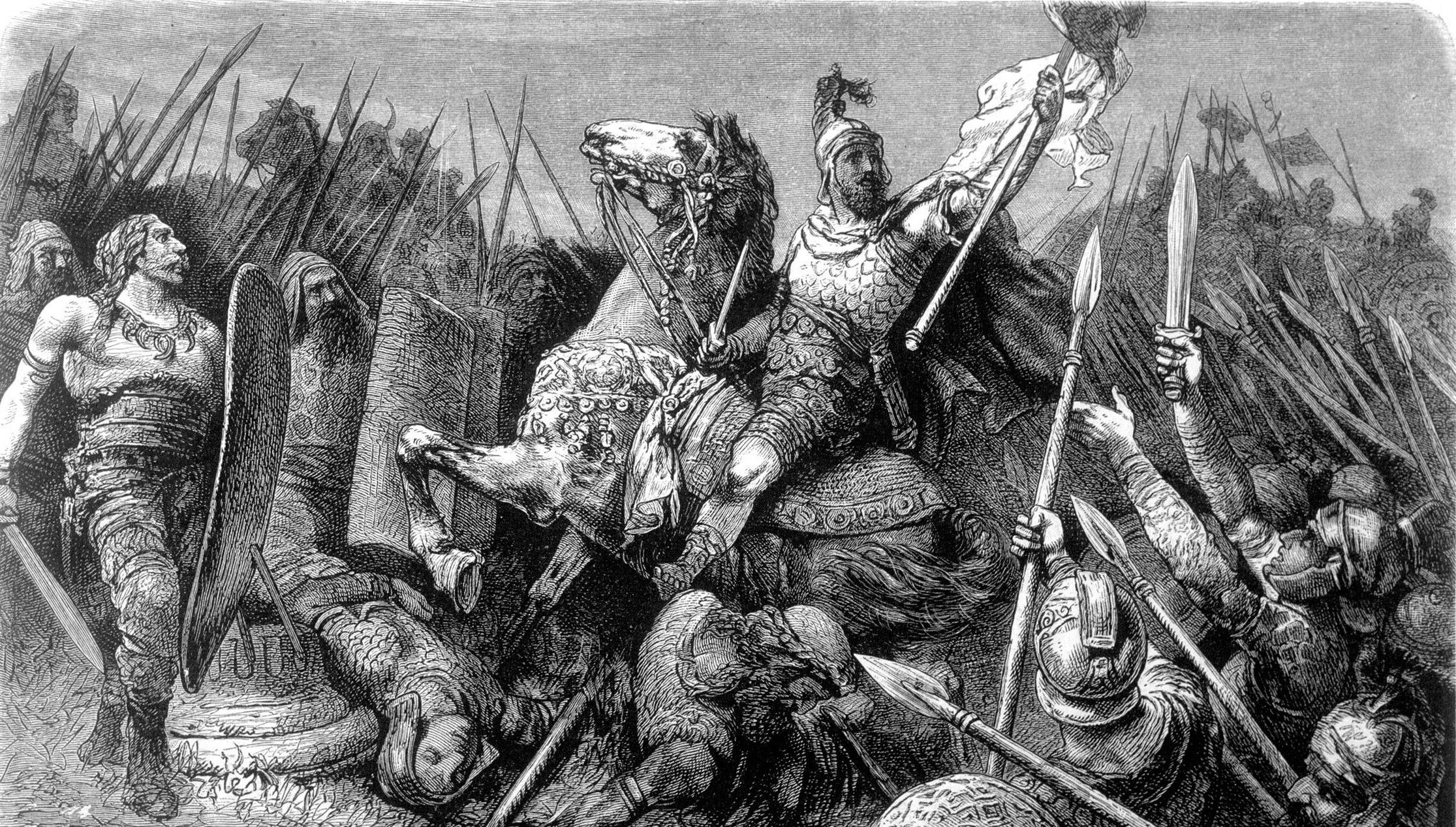

At this point, in late afternoon, while both sides were too hotly contested to give pursuit, Cleopatra’s rear-guard squadron of 60 ships, which had not yet fired a shot in anger, abruptly raised sail and raced through the center of the swirling melee, fleeing southward toward the safety of the open sea. Her move, although probably planned in advance, precipitated a general flight. Attempting to escape, the men of Antony’s ships began throwing their towers, catapults, and other furnishings into the sea in a desperate bid to lighten their ships. While thus engaged, Octavian’s forces fell upon them with a vengeance, crushing oars, snapping off rudders, scaling the boats, and climbing onto their decks to wrestle with their foes hand-to-hand. Antony’s men fought back with boat hooks, axes, stones and other heavy missiles, much as they would have defended a besieged fortress on dry land. The fighting was brutal and bloody.

Antony, upon seeing Cleopatra’s retreat, transferred his flag to a smaller, undamaged vessel and successfully slipped past Octavian’s line. The remainder of his fleet was not as fortunate, abandoned by its commander to an adversary who was ruthlessly intent upon its complete destruction. Octavian’s men began burning Antony’s ships, hurling blazing missiles at them from all directions. Lighted javelins or catapulted pots of charcoal and pitch added to the chaos. Greasy black smoke blotted out the horizon. The defenders, now leaderless, tried their best to ward off the missiles, but soon the timbers of the great vessels were hotly ablaze, creating a roaring inferno that was visible for miles around. Those who did not drown from jumping overboard in their heavy armor burned to death or smothered in the rising smoke and flames. By battle’s end, the sea was so choked with royal wreckage that the surface of the water was flecked with purple and gold in the evening twilight.

The destruction of Antony’s fleet was complete. From an original strength of 500 undermanned vessels, about 360, or roughly two-thirds, were captured by Octavian’s navy. Another 80 were destroyed or sunk outright during the battle, and fewer than 60 badly scarred survivors managed to evade capture along with Antony and flee to Egypt to meet up with Cleopatra’s squadron. Over 5,000 of Antony’s men died, twice as many as were lost by Octavian. The land forces on the opposing sides never engaged. More than a decade of civil strife and rivalry had been decided in a few short hours of naval combat. It was a loss from which Antony could never hope to recover.

The commander of Antony’s land forces in Greece, Publius Canidius Crassus, who had been ordered to lead them back to Egypt, simply abandoned the troops, some 19 infantry legions and 12,000 cavalry, and slipped out of camp under cover of darkness. He would later be captured and executed by Octavian—no one likes a craven traitor. The leaderless men promptly went over to Octavian. Thus augmented, the young emperor’s available strength rose to some 100,000 men. Octavian later founded a city at the site of his camp, which he named Nicopolis, or “city of victory,” forcibly herding the population of surrounding towns into the new settlement. In a temple to the gods commemorating his victory, Octavian displayed 120 of the bronze rams he had salvaged from Antony’s captured ships.

Antony and Cleopatra’s fates were not long in coming. While Cleopatra sailed directly back to Egypt, Antony made for Cyrene, in Libya, where he had assembled the remnants of his army. The local commander, Lucius Pinarius Scarpus, sensing which way the wind was blowing, refused to accept Antony’s messages or obey his orders. He even denied him entrance to the town. Thwarted in Libya, Antony moved on to rejoin Cleopatra in Egypt. There they spent nearly a year awaiting the dreaded arrival of Octavian and his troops.

Octavian’s victorious army advanced on Egypt via Syria and Judea, his forces swelling in size as many of Antony’s forces and former supporters switched allegiance and swore their loyalty to the winning side. Antony’s former troops in Cyrene joined the campaign and began moving in from the west. On reaching Alexandria in the summer of 30 bc, Octavian once again faced Antony’s forces. On July 31, Antony enjoyed one final small victory when his troops put to flight some of Octavian’s cavalry advancing on the outskirts of Alexandria. Antony settled down to wage one last massive battle, but was stunned the following day to see his entire cavalry force and what was left of his navy defect en masse before his very eyes. After being routed, the last of his infantry also surrendered. Later that day, Alexandria capitulated.

Cleopatra fled to her newly completed mausoleum. Antony attempted suicide by stabbing himself in the abdomen, but did not immediately die. He lived just long enough to be taken to Cleopatra, where he died in the arms of his erstwhile lover. Shrewdly, Cleopatra entered into negotiations with Octavian for her surrender. What exactly she was seeking was never recorded, but perhaps she felt that she could place the young general under her spell, just as she had done to Caesar and Antony before him. Whatever her intentions, it soon became clear that she had failed. To avoid being taken to Rome as a living trophy in Octavian’s victory procession, she committed suicide on August 9, supposedly availing herself of a poisonous asp smuggled into her cell in a basket of dates. On August 29 the people of Egypt proclaimed Octavian their new pharaoh, and Egypt became a much-prized possession of the Roman Empire.

Antony’s troops were sworn into Octavian’s service and then given their discharges. A few of Antony’s most ardent Roman supporters were executed, but most were granted clemency. Cleopatra’s son by Caesar, Caesarion, now 15, whom Octavian considered a threat to his claim of succession, was executed, as was Antony and Cleopatra’s oldest son, Antyllus, aged seven. Their youngest child, aged three, considered too young to be a threat, was spared and later appeared alongside a statue of Cleopatra in Octavian’s victory procession. Of Antony’s two sons by his first wife, Fulvia, the elder was executed, while the younger was married to his stepmother Octavia’s daughter from an earlier marriage, Octavian’s niece. He even reached the consulship in 10 bc, but later got back at Octavian for the death of his father by committing adultery with Octavian’s own licentious daughter Julia, and was executed for this outrage eight years later.

With Cleopatra’s death ended the Ptolemaic period of Egypt, the last time that country was ruled by a dynastic leader. Most of Antony’s former dispositions throughout the eastern empire were left in place, so long as their rulers now recognized the authority of Octavian. Octavian had reached the pinnacle of power, a journey that had taken him 14 years to achieve. He returned to Rome two years later, in 29 bc, amid tumultuous celebrations, and the vast wealth of Egypt began flowing into Roman coffers. A year later, in his mid-30s, Octavian declared himself emperor, taking the name of Augustus Caesar. He proved to be a competent, wise, and just ruler, ending years of civil war and strife and bringing Rome into its most glorious period of peace and prosperity.

Actium’s impact on history cannot be overestimated. It ended the eastern world’s influence on Europe for centuries to come. Such previously dominant kingdoms as Egypt, Greece, Babylon, Persia, Mesopotamia, and Assyria were never to rise again. From that time forward, Rome was the center of civilization, her culture, history, trade, politics, philosophy, laws, and language spreading the length and breadth of Europe. Even after the Roman Empire collapsed four centuries later, its influence endured. That influence was further spread to the New World when the European nations set out on their voyages of discovery and exploration. The direction that the world was eventually to take—east or west—was decided once and for all on a late summer’s day over two millennia ago at a little-known place called Actium.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments