By Melanie Savage

On May 15, 1862, a five-ship Union Navy squadron that included the ironclad USS Galena, gunboats Aroostook, Port Royal, Naugatuck, and the famous Monitor neared a bend in the James River known as Drewry’s Bluff, where Confederate Fort Darling commanded the passage. The flotilla had been ordered upriver to support Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s drive to seize the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, and put an end to the year-long rebellion.

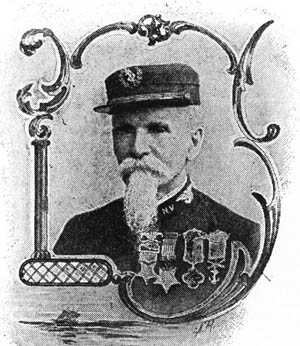

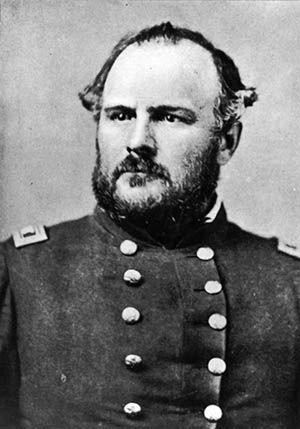

Aboard Galena was a 25-year-old silversmith from New York City, John Freeman Mackie, who had enlisted in the Marine Corps on April 23, 1861. After duty aboard the USS Savannah, he had been promoted to corporal and transferred to Galena. Mackie later described the river as being “crooked as a ram’s horn, with very high banks, heavily wooded on both sides, from which the fleet was constantly being fired on by Confederate sharpshooters hidden in the underbrush.”

After Galena opened fire on the fort, Confederate forces launched a fierce counterattack. Enemy shells raked the vessels as Confederate Marines manned the guns at Fort Darling, located atop a 100-foot cliff at a bend overlooking the waterway. Early in the bombardment, Commander John Rodgers, leading the Union flotilla, was severely wounded by a Confederate shell. Monitor was unable to level her 100-pounder Parrot Rifles and 9-inch Dahlgren guns, and was forced to withdraw. Naugatuck was also forced to move out of range after a 100-pounder gun exploded on her deck. Aroostook and Port Royal, both wooden hulls, were unable to withstand the furious barrage from the Confederate fortifications.

Leatherneck Warfare

Galena, the only remaining ironclad, was forced to fight alone for more than four hours. The ship took 28 hits, with 18 of those ripping through her armor. Sustaining 40 percent casualties, most of Galena’s naval gun crews were either killed or wounded. With a cry of “Come on, boys, here’s a chance for the Marines!” Mackie led a group of leathernecks to man the guns.

“As soon as the smoke cleared away a terrible sight was revealed to my eyes,” Mackie said later. “The entire after division was down and the deck covered with dead and dying men. Without losing a moment, however, I called out to the men that here was a chance for them, ordering them to clear away the dead and wounded, and get the guns in shape. Splinters were swept from the guns, and sand thrown on the deck, which was slippery with human blood, and in an instant the heavy Parrot rifle and Dahlgren guns were ready and at work upon the fort. Our first shot blew up one of the casemates and dismounted one of the guns that had been destroying the ship.”

By noon Galena was entirely out of ammunition, and Rodgers gave the command to move out of range. During the intense fighting at Fort Darling, 12 sailors and one Marine had been killed and 11 more had been wounded.

Mackie Receives the Medal of Honor

Reassigned to the USS Seminole, Mackie received the Medal of Honor on July 10, 1863, while anchored off Sabine Pass in Texas. His citation read: “On board the USS Galena in the attack on Fort Darling at Drewry’s Bluff, James River, on May 15, 1862. As enemy shellfire raked the deck of his ship, Corporal Mackie fearlessly maintained his musket fire against the rifle pits along shore and, when ordered to fill vacancies at guns caused by men wounded and killed in action manned the weapon with skill and courage.” When Commodore Percival Drayton presented the award to Mackie, he said, “Sergeant, I would give a stripe off my sleeves to get one of those in the manner as you got that.”

Reassigned to the USS Seminole, Mackie received the Medal of Honor on July 10, 1863, while anchored off Sabine Pass in Texas. His citation read: “On board the USS Galena in the attack on Fort Darling at Drewry’s Bluff, James River, on May 15, 1862. As enemy shellfire raked the deck of his ship, Corporal Mackie fearlessly maintained his musket fire against the rifle pits along shore and, when ordered to fill vacancies at guns caused by men wounded and killed in action manned the weapon with skill and courage.” When Commodore Percival Drayton presented the award to Mackie, he said, “Sergeant, I would give a stripe off my sleeves to get one of those in the manner as you got that.”

In January 1864, Mackie narrowly escaped death once again. While helping to suppress a riot at Sabine Pass, he was struck in the head with a chain hook that fractured his skull, a wound that never fully healed. Nevertheless, he returned to duty the following day. Mackie rose to the rank of orderly sergeant before receiving an honorable discharge from the Marine Corps on August 24, 1865, after four years of service. He eventually married and settled near Philadelphia. The Marine Corps’ first Medal of Honor recipient passed away in 1910 at the age of 74, boasting that he had never once been on the sick list during his entire time as a leatherneck.

Originally Published April 28, 2014

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments