by Robert Whiter

“And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air …”

That, as most people know, is a line from the American national anthem, words by Francis Scott Key, to the tune of Anacreon in Heaven by John Stafford Smith.

The incident that precipitated the anthem took place during the bombardment of Fort McHenry by the British on September 14, 1814 during the War of 1812. Bursting, or exploding, bombs (shells) had been in use in one form or another for quite awhile. Some authorities credit the Venetians in 1376 as the originators. Others, such as W.H. Greener, in his book The Gun and Its Development, give the honor to the Dutch.

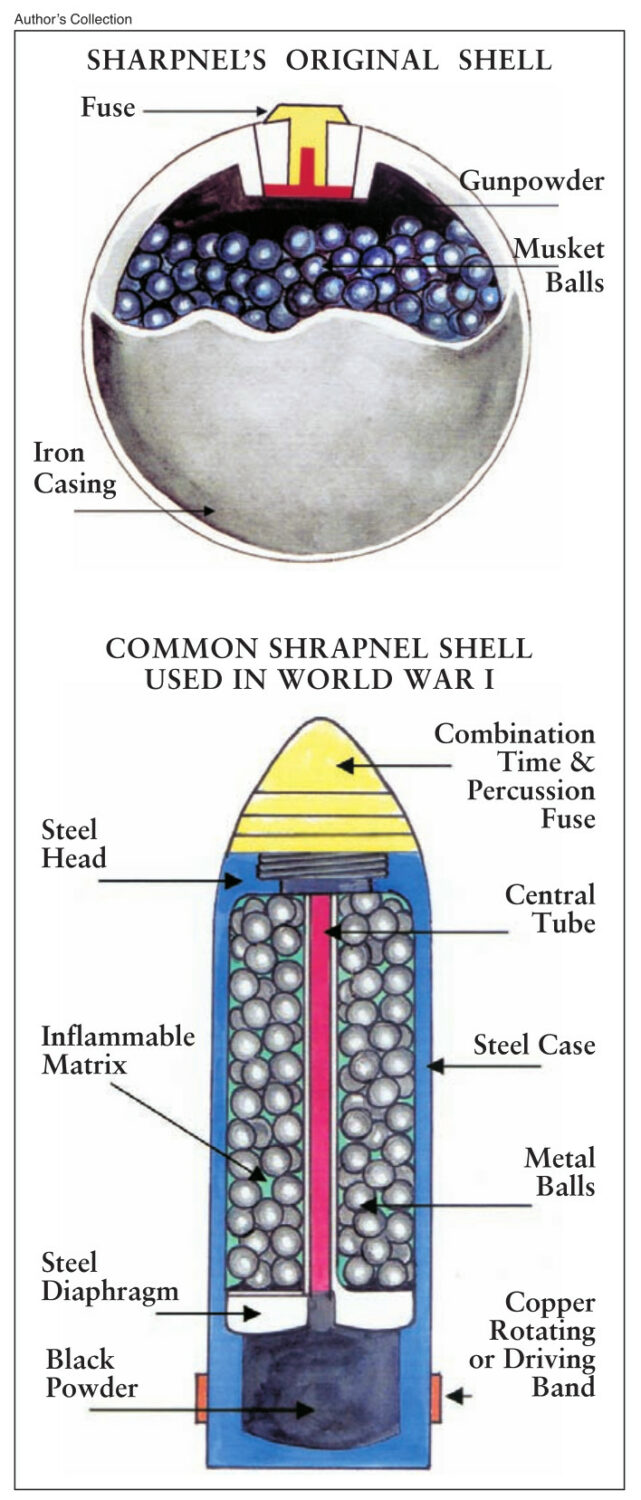

Basically, the exploding shell was a hollow cast-iron sphere filled with explosive, the filling hole being plugged by a fuse that was timed to detonate the gunpowder during the projectile’s travel. Its use was mainly confined to land operations, the shooting of any form of incendiary missile onboard ships being considered too dangerous. However, several tests were carried out by Deschiens in France and Sir Samuel Bentham who served with the Russian navy. The latter’s shells had considerable success against Turkish ships.

The French General Henri Paixhans also developed guns that gave the shell not only a high angle and muzzle velocity, but substantially increased the range. Additionally, tests had been carried out in England during the middle and late 1700s, but these had been delayed, to some extent, by premature exploding of the projectiles while still in the barrel.

It was around this time that a certain Lieutenant Henry Shrapnel was experimenting with his own exploding shells, and there is little doubt that it was the perfected variety of these that inspired Key to pen his immortal lines. The very first recorded tryout of his musketball-filled shells took place during the attack on Dutch Guyana. This resulted in the capture of Surinam (1804) and made an obscure artillery captain, one might say, into an overnight celebrity. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given the post of Assistant of Artillery. This enabled him to carry out tests of his various inventions and innovations at the iron foundry at Carron near Falkirk in Scotland.

Shrapnel Possessed an Imaginative Mind for Invention

Henry Shrapnel was the youngest of nine children born to Mr. and Mrs. Zachariah Shrapnel on June 3, 1761 at Midnay Manor House, Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire, England. Apparently his brothers died childless, so what little money existed passed on down to him. With this he was able, by living carefully, to have just enough to finance the numerous inventions that flowed from his fertile brain. Although his service life was spent in the army, it didn’t prevent him from submitting ideas to the navy. These included plans for improving the design and shape of certain warships and advocating replacing wooden vessels with iron-clads!

At age 18, Shrapnel entered the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, known to generations of budding engineers and gunners as “The Shop.” Among its many graduates may be found the following who achieved fame in the British Army: General Charles “Chinese” Gordon, Field Marshal Herbert Lord Kitchener, General Alan Cunningham and Maj. Gen. Orde Wingate, all “Sappers,” as the Royal Engineers are known. Shrapnel was the odd man out—he was a gunner.

‘Grapeshot’ Cannon

Right from the start there seems no doubt that Lieutenant Henry Shrapnel fully embraced every aspect of the science of artillery. Although most cannon fired some form of exploding (or perhaps disintegrating would be a more correct description) antipersonnel shell, they lacked the range so crucial in most battles. Generally known as “canister” and “grape-shot,” their maximum range rarely exceeded 300 yards. Canister shot consisted of a thin, metal, cylindrical case the same size as the caliber of the gun. This was filled with metal balls of either iron or lead. (Cases have been recorded where even stone pebbles were used.) Fired directly against the opposing forces, there was no exploding device inside the case. Air pressure, combined with centrifugal force, caused the shell to break up, after leaving the cannon, and shower the enemy with its contents.

“Grapeshot,” on the other hand, generally fell into two categories: “Caffin’s” Grapeshot consisted of a number of iron balls placed in layers between thin circular iron plates. These were arranged in banks (generally three) and held together by an iron bolt that passed through the center of the plates.

Quilted grape (thought by many to be the earliest type), on the other hand, was shot arranged around a spindle that was bolted to an iron tampion, or round bottom plate. The whole assembly was placed inside a canvas bag which, in turn, was intertwined with a quilting line or cord. The top of the bag was then drawn together and tightly tied under the cap at the top of the spindle.

Both types resembled a bunch of grapes—hence the term “grapeshot.” When fired, the shot disintegrated, distributing the balls with quite a deadly effect. But, as previously stated, the range was very limited. By way of interest, grapeshot could only be fired from an iron cannon as it needed a hard parallel bore. Bronze guns, which fired solid shot, were taboo. Long-range solid shot was fine for punching holes in fortifications, but, otherwise, it merely cut a narrow path through attackers.

It was during his four-year tenure at Woolwich that Shrapnel began seriously experimenting with an effective long-range bursting shell that could be used against massed troops. At first, he tried to improve on ideas already in use (e.g., a hollow ball filled with explosive and relying on the shattering of the outer shell into jagged fragments), but none met his exacting requirements. Finally, he took a similar hollow sphere and only partly filled it with explosive. The rest of the space he filled with musket balls. He added a fuse to the filling hole.

Perplexing Problems for Improving Ammunition

Two main problems bedeviled him. First, the casing had to be strong enough to withstand the initial propellant, but weak enough to be shattered from the bursting charge. Second, he required a fuse that would explode the shell at the required time.

But even when Shrapnel had finally solved these problems (as with most inventors) he had considerable difficulty in selling his product to the authorities, in this case, “The Ordnance Board.” Finally, on his return to Britain in 1784, he was able to demonstrate his “Spherical Case Shot” to the War Office. Even so, it wasn’t until 1803, as a captain and company commander of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Artillery, that his invention was finally adopted and went on to be successfully used, as previously stated, in 1804.

The succeeding years were to prove how effective Henry Shrapnel’s device was. Reports came in from around the world, and British gunners testified to its terrible power. The Royal Navy was quick to realize the new weapon’s potent capabilities in sea battles, for instance, clearing the decks of enemy ships. It is reported that Admiral Sir Sydney Smith (famous for his defense of Acre against Napoleon in 1799) was so impressed that he ordered a large quantity of the bursting shells, paying for them out of his own pocket.

Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops had emerged mostly victorious from engagements with some of the world’s finest armies, but received a nasty setback when they encountered the new weapon for the first time. This occurred during the Peninsular War at the battle of Vimeiro on August 21, 1808. It is recorded that, when Napoleon heard of the British victory, he sent an order that a secret tour be made of the battlefield in case there were any unexploded cannon balls still lying about. He wanted his ordnance specialists to examine and determine how the shells worked. If this account is true, it would show the importance Napoleon, an artilleryman himself, placed on this new weapon.

Indeed, there are many military students who are of the opinion that Shrapnel’s murderous creation went a long way to being one of the decisive factors at Waterloo. General Sir George Wood, Wellington’s artillery commander, went so far as to state, “Without Shrapnel’s shells, the recovery of the farmhouse at La Haye Sainte, a key position in the battle, would not have been possible.”

An Unrewarded Genius

Yet, in spite of all this, fate and fortune in the main eluded Henry Shrapnel. Visitors to the United Kingdom will search in vain for any statue or monument. The principal reason, paradoxically, was the importance of his invention. For one thing, it was purposefully kept secret by order of the Duke of Wellington himself. Even while Shrapnel was alive, financial reimbursement was slow, although the government finally awarded him a pension of 1,200 pounds.

In the 1820 Royal Military Calendar, Shrapnel was accorded a mere eight lines, while numerous other minor martial men were given copious writeups. Probably the unkindest cut of all was when, nearing retirement as a major general on relatively modest means, he heard that his monarch, William IV, who had promised him a baronetcy, had died before conferring it! Shrapnel died aged 81 at Peartree House in Southampton in 1842. His wife of over 30 years buried him in the family vault in the chancel of the church at Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire.

Shrapnel’s son, Henry, Jr., made a collection of his father’s effects, which included drawings and letters of commendation from the Duke of Wellington and other dignitaries of the nation. Taking them with him, he emigrated to Canada where, to all intents and purposes, the artifacts have remained.

With the development of breech-loading field guns and howitzers and the perfection in rifled barrels (circa 1885), Henry Shrapnel’s hollow ball took on a new shape, i.e., cylindrical with a cone-shaped head. The latter consisted of a time-and-percussion fuse and was screwed to the hollow body. This contained the balls imbedded in resin. Beneath these was a steel diaphragm and the bursting charge. This was set off by a flash down the central tube coming from the time fuse which, in turn, drove the balls forward, forcing off the cone-shaped head.

Various methods were tried to ensure that the shell gripped the rifling. One of the earliest systems was Sir William George Armstrong’s (Engineer of Rifled Ordnance at Woolwich), by which the whole shell was coated with lead. Not only was this necessary to give the shell its spin, but also to guarantee complete sealing of the gases following the shell, thus giving maximum propulsion. Unfortunately, it was found that, owing to the heat generated during discharge, a great percentage of the lead tended to melt and fall away. After trying numerous other ideas, it was found that the copper driving or rotating band at the base of the shell proved the most effective.

Shrapnel’s Legacy

World War I proved to be the nemesis of the shrapnel shell. Once the opposing armies had dug in, the shower of balls that had been so effective against massed troops in the open were of little consequence against soldiers ensconced in fortified dugouts. Shrapnel shells were not even potent enough to destroy barbed- wire defenses, the destruction of which was so necessary before making an attack on the enemy’s position.

Shrapnel’s name lives on in military nomenclature, although, to most people, it refers to the jagged fragments of an exploded shell or grenade casing. (Technically speaking, these should be referred to as shards, splinters, or shell fragments.) My own mother could make this mistake. I can recall that while on a leave in London during World War II, and during a lull in the course of an air raid, I wished to leave the family shelter and bring back some refreshments. My mother cautioned me to put on my “tin hat” because she was sure she could still hear “shrapnel” from the antiaircraft shells hitting the ground!

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments