By Jonas L. Goldstein, LCDR, USN (Ret.)

The Carthaginian hero Hannibal Barca has long been considered to have possessed one of history’s greatest military minds. Surely as a tactician and leader of men he deserves to be rated highly. But when one considers the broad span of his accomplishments, they seem temporal, and in the end, at the Battle of Zama, they spelled catastrophe for both himself and Carthage.

Many of Hannibal’s attainments were so spectacular that they blur the shortcomings of his strategy. I submit that while Hannibal was a tactical genius and a great leader, he failed as a strategist. Surely crossing the Alps from Spain in 218 bc and spreading havoc on the Italian peninsula for an extended period are feats of gargantuan proportions, yet for all this, Hannibal did not debilitate Rome to the point of surrender, nor was he able to frustrate the rise in Spain of Publius Cornelius Scipio, who was to be the instrument of his eventual fall. Let us consider the Second Punic War and its culminating battle at Zama.

Following the first encounter between Rome and Carthage over control of the western Mediterranean, there was a period of peace. The terms imposed by Rome were harsh, but did not significantly debilitate the African nation. Following the struggle, while Rome was occupied with the Gauls in the northern extremities of Italy, Carthage expanded into Spain. Hamilcar Barca, who had been active in Sicily during the First Punic War, never accepted the terms imposed by Rome, and his move into Spain was motivated by his desire to build power there as a stepping-stone to an attack on the Italian peninsula.

Hamilcar recaptured territory in Spain that had previously been under Carthaginian control. The political leaders of the Punic (that is to say, Carthaginian) nation were reluctant to give him all the support he desired, for fear he would provoke another war. Therefore, he built up his army with native recruits, and financed and equipped it with the products of Spanish mines. He enjoyed initial success, but was killed leading a charge against a Spanish tribe in 229 bc.

Everything That Befell them Was Caused by Hannibal

Hamilcar left behind his son-in-law Hasdrubal, and his sons Hannibal, Hasdrubal, and Mago. His son-in-law was chosen to succeed him, and for eight years he managed to win the cooperation of the Spaniards and built a great city, Nova Carhago, near the silver mines. When he was suddenly assassinated, Hamilcar’s eldest son, Hannibal, was chosen as leader of the army. At the time, he was 26 years old, and had been raised as an enemy of Rome. He would become the driving force of the Second Punic War. As Polybius wrote: “Everything that befell both peoples, the Roman and the Carthaginian, originated from one effective cause—one man and one mind—by which I mean Hannibal.”

As a youth, Hannibal had received a gentleman’s schooling in the languages, literatures, and histories of Phoenicia—Carthage being of Phoenician origin—and Greece. After joining his father in Spain as a young man, he received 19 years of training as a soldier. According to the Roman historian Livy, “He was the first to enter the battle and the last to abandon the field.”

Previously, in the year 226 bc, Hasdrubal had signed a treaty with the Romans, who were becoming increasingly concerned with his expansion into Spain. This agreement forbade the Carthaginians’ crossing the Ebro River in their expansion northward. But in 219 bc, Roman agents organized a coup d’état in the city of Saguntum. In doing so, they set up a government hostile to Carthage. Hannibal demanded its surrender. When the native leaders refused, he besieged the city. While there is consensus among historians that Saguntum lay south of the Ebro, the Romans interpreted this attack as an infringement of the agreement that they had signed with Hasdrubal. According to Polybius, the two immediate causes of the Second Punic War were, first, the siege of Saguntum and, second, Hannibal’s crossing the Ebro to initiate his campaign against Italy.

The Second Punic War lasted 17 years and was larger in scope than the first conflict between Carthage and Rome. Initially, the Romans did not consider Hannibal a serious threat. While he possessed a fine army, he had no fleet to transport his troops to the Italian peninsula. In addition, if he tried marching northeast toward Italy, he would reach the Alps, which the Romans believed no army could safely cross. They therefore thought that he would return to Africa to defend his homeland.

Crossing the Unforgiving Alps

But the brilliant Carthaginian had other plans. He intended to cross the Alps no matter what the cost and gain entry into northern Italy. He hoped to exploit the unrest among the Celtic tribes, thereby gaining powerful allies against the forces of Rome. To make his plan work, he would have to get to southern Gaul and march toward the Alps before the Roman force, which was sent to attack him in Spain, landed in the area. As the Cambridge Ancient History notes, “Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps has stirred the imagination and provoked discussion of succeeding ages.… The feat of crossing the Alps was in itself nothing remarkable.… Hannibal’s difficulties were in the first place military, owing to the hostility of the Allobroges—difficulties which beset armies marching in column in narrow defiles—but more important was the fact that it was now past the first week of September, and a heavy fall of new snow made the descent on the southern side particularly hazardous for the transport and elephants.… His losses in the Alps were such that he arrived in Italy with no more than 20,000 foot and 6000 horse.”

After the grueling ordeal in the mountains, and more than five months after leaving Spain, Hannibal led his men into the Po Valley. Meanwhile, Cornelius Publius Scipio, realizing that Hannibal was threatening northern Italy, sent his own army on to Spain, and then returned to Italy and assumed command of Roman troops preparing to stop Hannibal. The other consul, Tiberius Sempronius Longus, was in Sicily preparing to invade Africa. When word of the Carthaginian’s arrival in northern Italy reached him, he rushed northward.

Emergency Dictatorship

There followed a series of battles in which Hannibal proved to be vastly superior in generalship to the Romans. These victories included a skirmish near the Tacinus River in which Scipio himself was badly wounded, the Battle of Trebia in 218 bc, and the Battle of Lake Trasmene in 217 bc. Rome realized that its very existence was threatened and took the extraordinary measure of appointing a “dictator” to more efficiently counter the Carthaginians.

The man they chose was Fabius Maximus, an aristocrat and military man known for his sound judgment. Fabius formulated a strategy based on the premise of not meeting the Carthaginians directly, but harassing them as opportunity allowed. Thus for a time, significant defeats were avoided. Wrote the Roman historian Livy: “In Italy the wise delaying tactics of Fabius had broken the terrible continuity of Roman defeats. These tactics gave Hannibal much cause for anxiety, as he could see that at last the Romans had chosen a war leader who, instead of trusting to luck, was capable of a rational plan of campaign.”

In time, the purposeful delays of Fabius raised resentment in Rome, which had always been an aggressive political and military state. The Battle of Cannae stemmed from this resentment. Minucius Rufus, deputy to Fabius, was a member of a faction antagonistic to the Fabians. His officers shared his loathing of the bloodless delaying tactics of the old dictator. Therefore, when Fabius was summoned to Rome for consultation, Minucius seized the opportunity and attacked a Carthaginian outpost, driving the enemy into retreat. This was a minor engagement; however, Minucius inflated its importance in his report to Rome. As a result, he was honored by appointment as codictator. Fabius made no objection.

By law, the time had come for the dictatorship to end. In 219 bc the required annual election named Lucius Aemilius Paulus and Caius Terentius Varro as consuls. Paulus, an aristocrat, counseled caution; while Varro of the plebeians urged action and in the end prevailed. A minor incident occurred that was to shape Roman history. Hannibal had seized still another grain depot, this time in the half-ruined stone village of Cannae on the Adriatic shore. This resulted in the Senate’s ordering Roman forces to unite against the Carthaginians. The new consuls took command.

50,000 Romans Died

The two armies met on the plain of Cannae, and after a furious battle displaying Hannibal’s tactical genius, the huge Roman army of Paulus and Varro had been destroyed. Fifty thousand Romans died at Cannae, while 4,500 captives were taken. The Carthaginians lost 5,710 killed or wounded.

Historians have long debated whether Hannibal, after this great victory, should have immediately attacked Rome itself. No matter what the temporal considerations of the time, the failure of Hannibal to attack the jugular of his enemy after Cannae proved to be a cardinal error, which allowed Rome to regroup and in the end defeat the Carthaginians on the plains of North Africa.

Livy relates that after the battle “the victorious Hannibal was surrounded by his officers offering their congratulations…, Maharbal, however, the commander of his cavalry, was convinced that there was not a moment to be lost. ‘Sir,’ he said, ‘if you want to know the true significance of this battle, let me tell you that within five days you will take your dinner, in triumph, on the Capitol. I will go first with my horsemen. The first knowledge of our coming will be the sight of us at the gates of Rome. You have but to follow.’

“Hannibal replied: ‘I commend your zeal, but I need time to weigh the plan which you propose.’ To this the cavalry leader replied: ‘You know, Hannibal, how to win a fight; you do not know how to use your victory.’” Livy felt that the day’s delay was the salvation of the City and of the Empire.

Hannibal’s War of Dominion

Although urged to advance on Rome by some of his generals, Hannibal decided to pursue his former policy of attacking Rome’s allies in Italy rather than striking a deathblow at his enemy. As he decreed in an address to the captive Roman soldiers, who were awaiting their ransom, he was not waging a war of extermination; rather he was fighting to maintain the rank of his nation and to achieve hegemony.

Hannibal expected Rome to sue for peace. He wanted a victory recognized by a treaty that would overturn the humiliating situation engendered by the treaties of 241 bc, which dictated the loss of Sicily and the obligation to pay a heavy indemnity, and that of 236 bc, which resulted in the loss of Sardinia. To achieve this, Hannibal conducted intense diplomatic activity in the south of Italy, whose states had been demoralized by Cannae. His plan was to contain Rome north of Campania, while establishing a de facto protectorate over southern Italy. This strategy could have been generated by the realization that, even after Cannae, Rome possessed considerable strength, and Hannibal would be bogged down in a lengthy siege, which in time could erode his position throughout Italy. In addition, his government had never furnished him with siege machines that would undoubtedly have been required for any successful attack on Rome proper. However, these considerations were not of sufficient moment to deter a powerful thrust toward the city to achieve final victory.

The most significant Roman threat to Carthaginian hegemony came in Spain, where the Scipios were again establishing Roman dominance. When the elder Scipio died, the son of the consul Publius Cornelius Scipio, who later came to be known as Scipio Africanus, took command. He was influenced by Hannibal’s brilliant battlefield maneuvers, employing many of his opponent’s ideas, as well as some of his own. Polybius wrote that “Scipio … strengthened the confidence of the men under his command and their readiness to face dangerous enterprises by instilling into them the faith that his plans were divinely inspired. The fact remains, however, that his actions were invariably governed by calculation and foresight.”

At the Battle of Ilipa in 206 bc, the Romans, using their revised tactics, defeated the Carthaginians under Hasdrubal, son of Gisgo. As the classical scholar H.H. Scullard wrote: “Ilipa was the justification of Scipio’s military reforms and methods, and of his whole policy. By it the fate of Spain was sealed and the Carthaginian cause there forever lost.”

At this point, the character of the Second Punic War changed radically. For more than a decade, while battles raged in Italy, Spain, and other lands, the Carthaginian homeland in northern Africa had remained untouched. Now, with Spain firmly in their hands and Hannibal roaming the southern Italian mountains, the Romans were able to reallocate their resources. Thus, Carthage became the main focus of military operations.

The catalyst in this dramatic shift was Publius Cornelius Scipio (Africanus). After wresting Spain from Carthage in 206 bc, he emerged as Rome’s chief military figure, and it was he who proposed carrying the war to Africa. After much debate, the Roman campaign against Carthage was approved.

Scipio utilized Sicily as a staging point for his operation. Here, he took a disorganized band of volunteers and trained them to be the nucleus of an effective expeditionary force. From the beginning, he concentrated on building a superior cavalry. In this regard, Scipio had admired the Numidian Masinissa, who had fought with the Carthaginians in Spain, and the Roman leader convinced him to join his campaign in Africa.

Truce or Ruse at Carthage?

Scipio took a year to build up his forces. As the Cambridge Ancient History relates: “In the spring of 204 bc, Scipio set sail from Lilybaeum with a squadron of forty quinqueremes to cover the transports which carried his army, probably amounting to about 25,000 men. The Carthaginian naval strength had sunk so low since their defeat in 208 bc, that there was little danger of any hindrance to the Roman invasion.”

The army disembarked at the Fair promontory (now Cape Farina), a few miles from Utica. Seeking to secure a base of operations, they made a preliminary move against the city. But it was not successful and Scipio retired to winter quarters to build up his strength and supplies. Finally the Carthaginians accepted a truce, which has been generally interpreted as a ruse to gain time until Hannibal could be recalled from Italy. After some diplomatic double-dealing on the part of the Carthaginians, Scipio decided to renew operations for a final trial of strength.

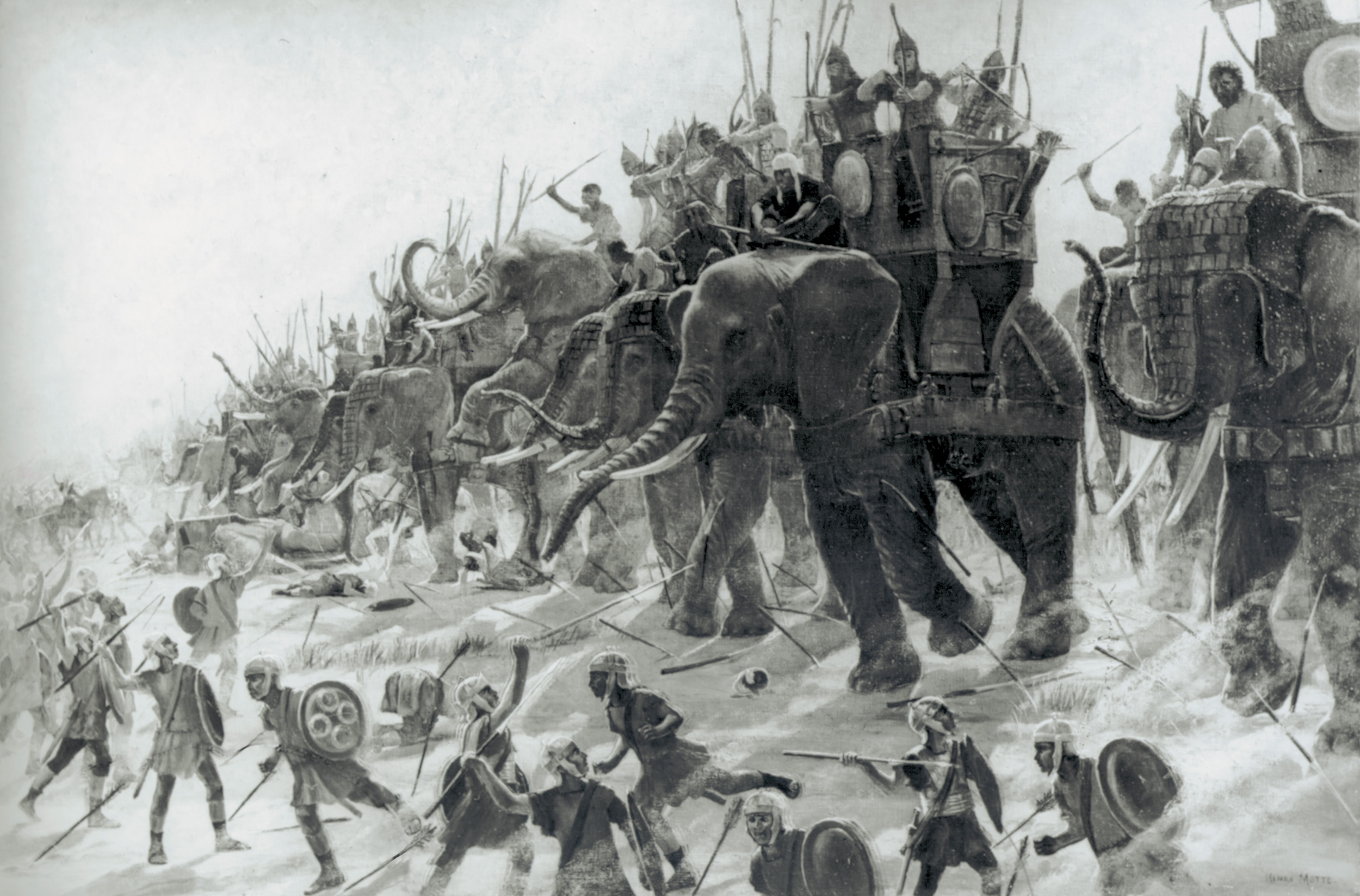

Hannibal collected his army and at the urging of the Carthaginian government moved against Scipio. All of Carthage’s hopes rested on his generalship. When he had entered Italy he was 29. Now he was 45. On returning to Africa, he raised a powerful army made up of a mixed force of mercenaries and Carthaginians, totaling between 40,000 and 45,000 men. He also had 80 elephants, more than he had used in any previous battle. On the other hand, Scipio had between 36,000 and 40,000 men, including Masinissa’s cavalry.

Hannibal marched his army westward in pursuit of Scipio, and after a few days, his scouts reported that the Romans were camped at the town of Zama, located on the edge of a plain about 75 miles southwest of Carthage. Scipio captured three of the Carthaginian scouts. To Hannibal’s surprise, he gave them a grand tour of the Roman camp and released them, thereby flaunting his confidence of victory. Hannibal was so impressed that he requested a meeting, an invitation Scipio accepted.

The next day, with a small escort of horsemen, the two met at a designated location. Livy describes the site as follows: “Scipio established himself near Naraggara in a favorable position within javelin-range of water; Hannibal occupied a hill four miles away, safe and convenient enough except for its distance from water. Between the two positions a spot in full view from every side was chosen for the meeting, to ensure against a treacherous attack.”

“Either Put Yourselves and Your Country at Our Mercy or Fight and Conquer Us.”

Hannibal and Scipio then walked forward, accompanied only by interpreters. Hannibal asked Scipio if they could resolve their differences without fighting. Scipio replied that the war and its cost in human suffering had gone on too long for him to back down now. He concluded, “Either put yourselves and your country at our mercy or fight and conquer us.” With that, the two greatest generals in the world parted and returned to their armies, their differences to be resolved in blood. As Polybius points out, “The Carthaginians were fighting for their very survival and the possession of Africa, the Romans for the empire and sovereignty of the world.”

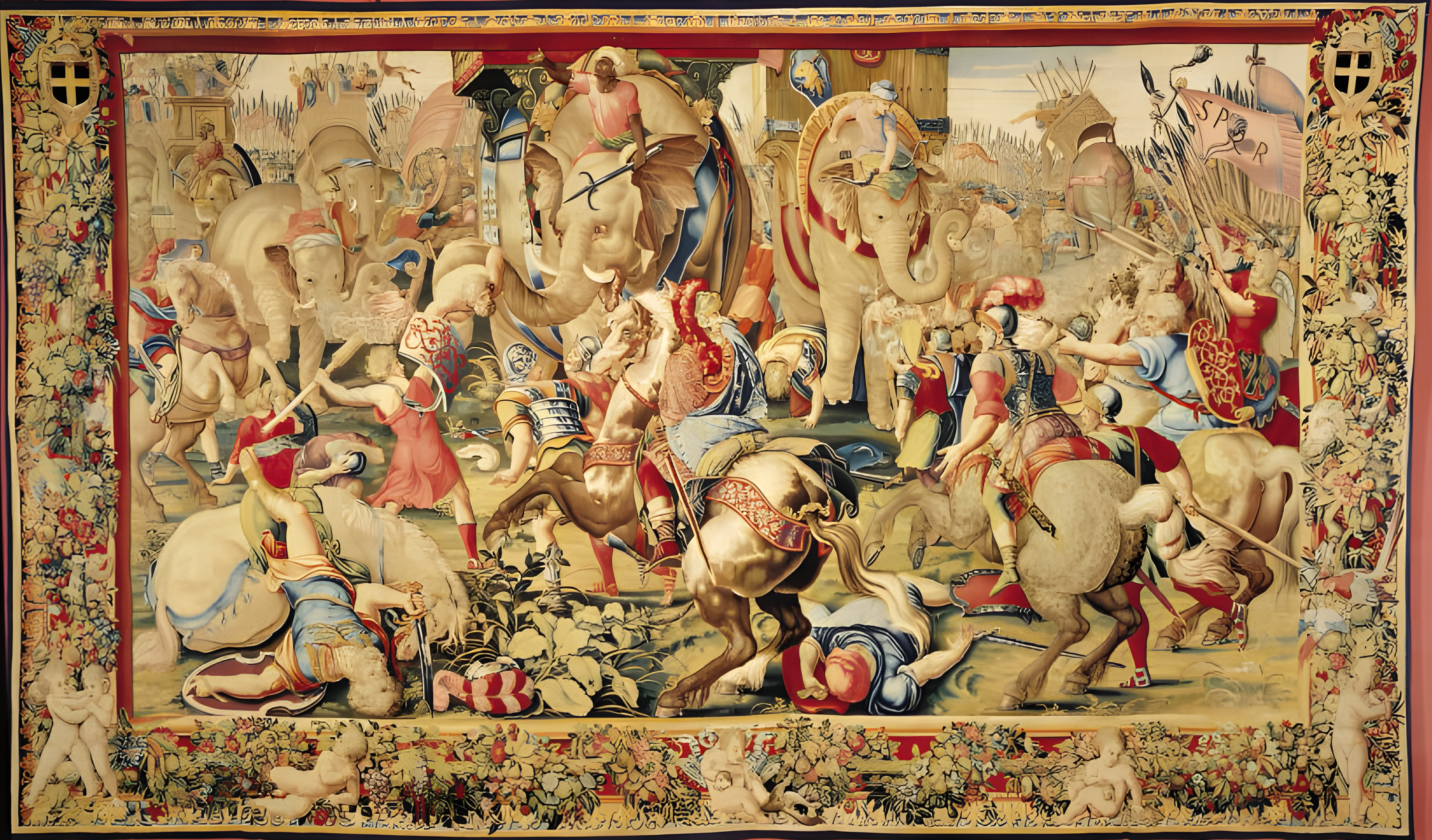

As the battle started, Hannibal did not form his usual long battle line; rather his forces consisted of three elements: (1) the Ligurians and Gauls, (2) the Carthaginian recruits, and (3) Hannibal’s veterans. These segments advanced separately in three waves. And ahead of all went the elephants. As Hannibal moved, the Roman alignment was already proceeding toward him, with its horsemen keeping a slow pace. The line of infantry advanced in the usual three ranks: the front, the spearmen, and the supporting triarii.

Perhaps it would be useful at this point to define the terms involved in describing the Roman formations. The heavy armed infantry was arranged in three lines, the first called the hastati, the second the principes, and the third, the triarii. The latter were armed with a sword and a thrusting spear, not the throwing spear used by the first two lines. All the maniples (subdivisions of legions and consisting of 60 to 120 men) had open lanes between them—openings screened only by light-footed javelin throwers.

Suddenly all the Roman trumpets and horns sounded in a single blast, startling the line of elephants. The beasts turned into the openings between the maniples to be met by showers of missiles. They either turned back or raced forward through the lanes. In a few minutes they were out of hand and virtually out of action except for the confusion they left behind them. At this point Scipio ordered his mounted wings forward. The Carthaginian horses were too few to check the charges of the trained Roman squadrons. Soon all the riders swept away over the plain and vanished from sight.

In the center, Hannibal’s Ligurians and Gauls rallied, and the Roman advance was stopped. The triarii came through the intervals and again moved forward. Wrote Polybius: “The steadiness of their ranks and the superiority of their weapons enabled Scipio’s men to make their adversaries give ground. All this while the rear ranks of the Romans kept close behind their comrades and cheered them on, but the Carthaginians by contrast shrank back in cowardly fashion and failed to support the mercenaries.” Hannibal had ordered his formations to keep apart. When the survivors of the first wave retreated, they found their Carthaginian allies with weapons poised against them.

Behind the Dead Stood Hannibal’s Army of Italy

The Roman line continued to advance on Hannibal’s second army, the Carthaginians. Livy describes the lurid scene in the following terms: “But such heaps of dead men and their arms filled the place where the auxiliaries had been standing a short time before that the Romans began to find it almost more difficult to make their way through them than it had been through the dense ranks of the enemy.” Their pressure intensified as the second-rank spearmen joined the combat. It was late in the morning when the Carthaginians were broken. Behind the dead stood Hannibal’s army of Italy. These tough troops had been purposely held back for the final phase of the battle.

At this point, although he could not retreat, Scipio demonstrated his genius by having trumpet calls sounded from end to end of the legions. Orders reached the men in the ranks to rest and clear the ground. Scipio waited until his men had regained their strength. Then he changed his formations. The spearmen who had been in support of the front line marched off to one flank, the triarii to the other. The Roman front lengthened, extending beyond Hannibal’s. Then it advanced again in a long, thin line that closed in on the weak enemy flanks. At that moment, the Roman horsemen returned and charged into the rear of Hannibal’s veterans. The encircled troops could not escape. They fought where they stood until most of them died. When an opening appeared, Hannibal and a few riders got away. As Livy relates: “It was this cavalry attack which finally defeated the Carthaginians. Many were surrounded and cut down where they stood; many scattered in flight over the open plain, only to fall everywhere beneath the cavalry, the undisputed masters of the field.”

At least 10,000 Carthaginians had been slain and another 20,000 or so were now captives. Roman troop losses were probably not more than 4,000 killed, although a much larger number undoubtedly were wounded. Hannibal escaped to his base at Hadrumentum. Scipio did not pursue him. After sacking the Carthaginian camp, he marched to the coast. But the Carthaginians were not willing to stand a siege, and Hannibal used all his influence to persuade them to accept the best terms they could obtain. The conditions finally concluded left Carthage in possession of her own territory in Africa.

Scipio brought riches back to Rome and bathed in the glory of victory, but the saga between Hannibal and Rome would revive, and the abrasion between Carthage and Rome would only reach its finality in the second act of the Punic Wars.

The Romans’ success in Spain, finalized at the Battle of Ilipa, gave Rome the hero they needed, and he in turn formulated a strategy that not only forced Hannibal out of Italy and onto the plains of North Africa, but also led to the Battle of Zama. Victory there eliminated Carthage as a major threat to Rome and its ultimate destruction. The fact that Hannibal did not even try to strike at the heart of Rome after Cannae, instead pursuing a soft policy toward eventual hegemony, remains a false strategy in the eyes of history, especially when contrasted with that of Scipio Africanus who did not dally on the Italian peninsula, but grasped the jugular vein of his enemy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments