By William E. Welsh

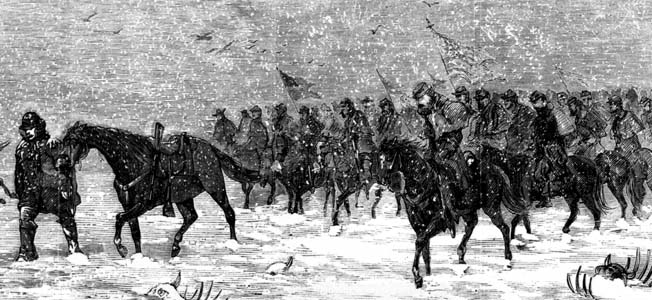

Deep ranks of Federal troops moved steadily across the valley floor toward Missionary Ridge late in the afternoon on November 25, 1863. Four divisions with national and regimental flags borne proudly aloft steadily pressed back thin lines of Confederate troops who unwisely were in advanced positions in front of their breastworks.

In many places, the Yankees arrived at the works at the base of the ridge simultaneously with the retreating Confederates. The bluecoats who reached the trenches fired to their left and right. In some places the combatants swung muskets or lunged at each other with rifles tipped with foot-long bayonets. Resistance at the base of the ridge was short-lived or nonexistent.

Bullets From Above

The Yankees had control over the first line of Rebel works by 3:30 PM. Two other lines of entrenchments stretched the length of the ridge like seams on a pair of trousers. A second line was halfway up the 400-foot ridge, and a third line at the top of the ridge. As the Yankees milled about, bullets from above hit many of them with a dull thud, knocking them to the ground. Angered by the plunging fire, the Federals began to ascend the hill. At first they did so in squads, but soon it was companies or regiments.

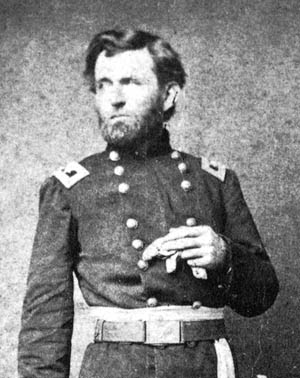

The two Federal divisions in the middle belonged to Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger’s IV Corps, and the two divisions on the outside belonged to Maj. Gen. John Palmer’s XIV Corps. All belonged to Maj. Gen. George Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland. From Orchard Knob, an advanced position midway between Chattanooga and Missionary Ridge, Thomas observed the battle with his superior, Military Division of the Mississippi Commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

“Thomas, Who Ordered Those Men Up the Hill?

The Federals had orders to seize the enemy works at the base of the ridge as a diversionary attack to assist the main Federal attack on the Confederate right flank being conducted by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee. Thomas and Grant soon observed the entire Union line surge up the ridge.

Two days before, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s Command, which had been transferred from the Army of the Potomac, had driven the Rebels from Lookout Mountain on the Confederate left flank. The following day, Thomas’ men had seized Orchard Knob.

“Thomas, who ordered those men up the hill?” asked Grant. “I don’t know. I did not,” replied Thomas. Grant asked Granger, and he got the same response. Grant warned those with him that if the charge toward the crest was unsuccessful, then someone would be held accountable.

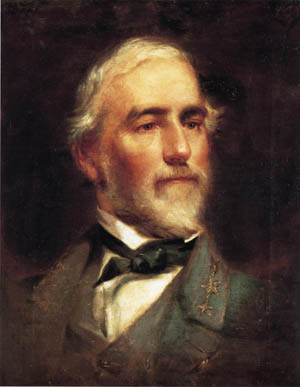

Another Hail of Rifle Fire

The Confederates were uneasy when they saw the Union advance begin in the late afternoon. “I noticed some nervousness among my men as they beheld this grand spectacle, and I heard remarks which showed some uneasiness existed,” wrote Brig. Gen. Arthur Manigault, who led a brigade of Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s Corps situated in the center of the Confederate line. Although it would seem as if the Confederate defense in depth was sufficient to resist a major assault, it suffered from a number of weaknesses, such as placement of the third line on the topographical crest of the ridge rather than on the military crest.

As the Yankees ascended the ridge, they endured a hail of rifle fire. As if that wasn’t bad enough, Confederate artillery crews rolled round shot with lit fuses down the hill toward them.

Nevertheless, the Yankees swept over the second line of entrenchments and continued their advance uphill. Soon the Yankees were scaling the final 100 feet of the ridge toward the last Rebel line. A Confederate engineer had done a poor job of laying out the line at the top of the ridge. In many areas, the Yankees were able to reach the last line without taking heavy fire.

A Full Confederate Retreat

“The retreat of the enemy along most of his line was precipitate, and the panic so great that Bragg and his officers lost all control over their men,” wrote Grant. When the Yankees reached the top, they saw panicked Rebels on the reverse slope tumbling down the mountain trying to escape death or capture. The Rebels were in such a panic that they tossed away their rifles, knapsacks, and blankets in an effort to lighten their load.

Thomas’ attack lasted slightly more than one hour and resulted in the capture of 37 guns (the equivalent of nine Confederate batteries) and 2,000 Rebel soldiers. The decisive victory forced the Confederates to retreat into north Georgia. With Chattanooga securely in their hands, the Federals would soon launch a drive toward Atlanta.

Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge are part of the sprawling Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park. Dedicated in 1895, the park has the distinction of being one of the earliest national military parks in the nation.

The Lookout Mountain Visitor Center

The Lookout Mountain visitor center is open every day of the year except December 25. Park rangers at the visitor center can furnish information on auto tours, day hikes, and the history of the mountain battles.

The Cravens House, which is halfway up Lookout Mountain, was demolished and rebuilt shortly after the war. It is open for tours in the summer. Atop Lookout Mountain there are several places from which visitors can obtain spectacular views of the land below the mountain. Garrity’s Battery offers a stunning view of Moccasin Bend, the western overlook near Van Den Corput’s Battery offers a dramatic view of Lookout Valley, and Ochs Memorial Observatory in Point Park on top of Lookout Mountain affords excellent views of the Chattanooga area.

As for Missionary Ridge, there is an eight-stop auto tour. Although each stop is worth visiting, the must-see stops are Orchard Knob, Sherman Reservation, and Bragg Reservation.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments