By Eric Niderost

Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson was not a happy man, and his sour mood was made worse by the weather. It was the evening of September 2, 1916 and slate-gray clouds were producing an incessant drizzle that dampened spirits as well as uniforms. Frequent rain is a fact of life in England, but to the 21-year-old Royal Flying Corps pilot the inclement weather meant another day of stultifying boredom.

Robinson was stationed at Sutton’s Farm near London, where a makeshift airstrip had been carved out of somebody’s pasture. Pilots and mechanics were gathered inside a crude canvas hangar, where the smell of damp air mingled with the pungent odor of oil, to vent their feelings of frustration. German airships, popularly called “zeppelins” after their original creator, had been bombing England with impunity since 1915. Despite their best efforts, the pilots of the Royal Flying Corps had been unable to down a single raider over home territory.

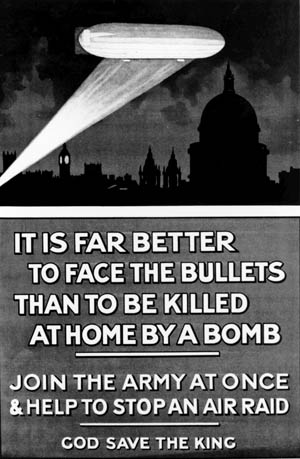

The young lieutenant paced the hanger like a caged tiger, blue eyes blazing with frustrated rage. Robinson was a tall man, about six feet in height, and like many pilots he had grown a mustache to give himself a military bearing and possibly hide his youth. “Look at this bloody headline!” Robinson shouted, pointing to a dog-eared newspaper clipping with the legend “What is the Royal Flying Corps Doing?”

Civilians didn’t understand. How could they? Zeppelin raids occurred at night, when flying was at its most hazardous. Robinson’s unit, “B” Flight, 39th Squadron of the Home Defense Wing, was flying BE-2Cs, a ubiquitous biplane that was the workhorse of the Royal Flying Corps. Slow but sure, the BE-2C was a stable aircraft—but its stability was bought at the price of maneuverability. It might seem a paradox to a civilian, but giant airships were hard to spot at night. Unless caught by a searchlight beam, or betrayed by the telltale flashes of detonating bombs it just dropped, a zeppelin was almost invisible in the dark.

But night landings for airplanes were the toughest challenge. Airfields were primitive, often scarcely more than dirt tracks, and crudely lit by rows of burning gasoline buckets. In 1915 alone, 87 British planes had attempted to intercept zeppelin raiders, all in vain. Of those 87, 15 had crash-landed.

English Pilots Scramble For Night Action

Robinson went over to his airplane, a black-painted BE-2C, serial number 2093. He inspected every inch of his machine, taking particular note of the Lewis machine gun that was mounted in the front. The BE-2C was a two-seater, but a gunner/observer was not used in the interests of speed and weight. Satisfied, the young lieutenant settled down in his cot for some sleep. His repose was rudely interrupted by the noisy jingle of a telephone. Groggily picking up the receiver, Robinson heard the words “Take immediate air raid action” crackle through the earpiece. The “show” was on; somewhere in the dark, enemy zeppelins were approaching London.

It was 11:30 pm when Robinson’s flimsy machine wobbled off the cow pasture runway and ascended into the pitch-black void. Little did Robinson know, but he and his RFC comrades were going to face the greatest airship raid of World War I. No less than 16 giant airships were lumbering toward England, intent on bringing London to its knees. Could Robinson and others like him stop this aerial onslaught? Only time would tell.

It was not surprising that Great Britain and Germany would find themselves on opposite sides during the war; they had been rivals since the turn of the century. Britain was the richest and most powerful nation on earth in 1900, a fact that excited the envy and admiration of rising powers like Germany. Its colonial empire was the largest in human history, encompassing one-fifth of the earth’s surface and boasting a population of 385 million.

When war came on August 4, 1914, German envy of things British turned to active hatred. Locked in a fearsome struggle with France along what later became the Western Front, Germany resented England’s alliance with its Gallic foes. Within weeks German public opinion was in favor of “punishing” England for its “transgressions,” real or imagined. “Gott Strafe England” (“God Shall Punish England”) was the national watchword, and there was no doubt, at least in German minds, that they would be the instruments of the Almighty.

English Isles Become Vulnerable From the Air

But how to attack England? It was an island, separated from the continent by a channel that, as Shakespeare put it, “served as a moat defensive to a house.” More importantly, this channel was patrolled by the powerful Royal Navy, historically the country’s first bulwark against invasion. Yet England was vulnerable from the air, and the zeppelin seemed tailor-made as an agent of aerial destruction.

Around 1914-15 conventional aircraft were still crude, almost rickety affairs, barely capable of takeoff, much less delivering any kind of significant bomb payload. Sleek and stately, capable of lifting several tons, hydrogen-filled airships seemed the future of aviation in peace as well as war. Is it any wonder, then, that German children sang a song in the autumn of 1914 that expressed the nation’s hopes as well as its aspirations? It ran, “Zeppelin, flieg, Hilf uns im Krieg, Fliege nach England, England wird abgebraunnt, Zeppelin, flieg.” (Zeppelin, fly! Help us in the war, Fly to England, England will be destroyed by fire, Zeppelin, fly!)

At the war’s outset the German armed forces were woefully ill prepared to carry out the song’s brave threat. In August 1914 the Naval Airship Division had only one zeppelin in service, while the army had six. Even that number was reduced when four of the German army’s zeppelins were brought down by enemy ground fire. In spite of public expectations it seemed the zeppelin had little future as a weapon of war. German admirals, conservative by nature, were lukewarm about airships but did concede their value for long-range reconnaissance missions at sea.

Into this confused situation stepped Kapitanleutnant (Lieutenant Commander) Peter Strasser, head of the Naval Airship Division since 1913. If the lifelong bachelor had a passion, it was airships, and he was a tireless advocate of their use. The army had been using zeppelins as low-level reconnaissance craft, with predictably fatal results. “Zeppelins are designed to fly high,” Strasser counseled, “operate at night or in cloud cover, and carry payloads of bombs or incendiary devices.”

Strasser’s arguments, fueled by an absolute and unwavering faith in the airship’s potential, began to bear fruit. The Fuhrer der Luftschiffe (airship leader) wore his superiors down with a barrage of reports, proposals, and conferences that hammered away resistance. Later, Strasser’s single-minded zeal would harden into fanaticism, but in the early years it served him well. Admiral Alfred von Tripitz sniffed that Strasser “was slightly mad and carried away with the idea that airships are more important than battleships.”

While his superiors hesitated Strasser took action, building new zeppelin bases at Towdern, Hage, Seddin, and Nordholz. He also ordered new zeppelins from the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin (Zeppelin Company), the original prewar manufacturer of the giant aircraft. It was immediately recognized that the exigencies of war demanded a tougher breed of zeppelin. The Zeppelin Company met the challenge. Dr. Paul Jaray, a leading designer who was an expert in aerodynamics, helped streamline the hull to reduce drag. New construction sheds were built at the company’s headquarters at Friedrichshafen, and an assembly plant established at Postdam, near Berlin.

Strasser’s hard work and perseverance paid off. By December 1914 the new zeppelins, L-4, L-5, L-6, L-7, and L-8 had been delivered to the Naval Airship Division (the “L” designation stood for “Luftschiff”). More were to follow. The Zeppelin Company’s efforts swung into high gear, and during its peak period from 1915 to 1917, it turned out an average of two airships a month.

Germany’s vaunted High Seas Fleet featured a stunning array of battleships, but relatively few destroyers or small cruisers. German military thinking of the time envisioned a decisive set-piece battle with the Royal Navy, a modern-day Trafalgar-in-reverse that would wipe away centuries of English naval supremacy. That battle never materialized, but in the meantime there was a lack of destroyers, those “eyes of the fleet,” to perform scouting missions. The Zeppelin admirably performed such reconnaissance duties. Weather permitting, the Naval Airship Division dispatched at least one zeppelin to search the North Sea for British submarines or surface vessels.

Army airship operations were more far-flung, and reflected the broad scope of its commitments. Bases were built on both the Eastern and Western fronts, and army zeppelins would eventually fly over France, Belgium, Poland, and Russia. In general the army sent its airships on nocturnal raids behind enemy lines.

Both services wanted to bomb London, but there was a major stumbling block. The German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, refused to grant permission for such a move. Known for his bombastic speeches before the war, the Kaiser was a humane man beneath the bluster. The Germans were already being called “Huns,” a reference to real or imagined atrocities in Belgium, and ironically the term derived from one of Wilhelm’s own speeches years before.

Churchill Orders Preemptive Attack On Zeppelin Sheds

The Kaiser also had blood ties to the British royal family. Britain’s Queen Victoria had been his grandmother, and the current monarch, King George V, was his first cousin. He was loath to order attacks on England, a country he knew well from visits and admired as well as envied. Above all, Wilhelm wanted to spare Germany the onus of killing defenseless civilians.

While the Kaiser vacillated, there was at least one man in England who took the zeppelin threat seriously. First Lord of the Admiralty Winston S. Churchill was known as something of a maverick, a politician whose fearlessness and occasional brilliance sometimes made him controversial. Churchill felt the best defense was offense, and he had the means at hand: the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS).

The First Lord authorized a bombing raid on the zeppelin sheds at Dusseldorf. This first effort proved abortive, and the Germans sustained very little damage in the event. About two weeks later, the tiny RNAS based in Antwerp, Belgium, decided to have another “go” at the airship sheds. Time was running out; German artillery was hammering at the gates of the city, and with Antwerp about to fall British evacuation was imminent.

British Finally Draw Blood In Attack On Zeppelins

Flight Lieutenant R.L.G. Marix climbed into his Sopwith Tabloid at 1:30 in the afternoon of October 8, 1914, his objective Dusseldorf. Marix managed to locate the zeppelin sheds, and despite heavy groundfire that riddled his machine, released four 20-pound bombs. There was an enormous roar, followed by flames and a thick black coil of smoke that ascended hundreds of feet into the sky. One shed was entirely consumed, along with the newly launched Z-9.

Marix had little time to savor the destruction of the Z-9; his machine was badly shot up and barely able to fly. He managed to stay aloft, and came within 20 miles of Antwerp before being forced down. Borrowing a peasant’s bicycle, he pedaled his way back to his aerodrome base, arriving just in time to be included in the general British evacuation at 6 pm.

The British had won the first round, but the Germans would soon retaliate. Kaiser Wilhelm finally bowed to pressure and on January 10, 1915, sent a telegram that authorized air attacks on England. The kaiser still harbored notions of “civilized war,” however, so the airships were to bomb only military targets—shipyards, arsenals, and military establishments—on the lower Thames River or on the coast. London was to be strictly off limits.

Now, at last, there would be Luftschiffangriff gegen England—airship raids against England. The kaiser’s directive was welcome news to Naval Airship Division chief Peter Strasser. There were many details to be worked out, partly by meticulous planning, and partly by trial and error. Strasser was ably seconded by Dr. Hugo Eckener, a major figure in the development of zeppelins and the training of their crews before the war. Eckener and Strasser became close friends, and nicknames were coined in token of their genuine bond. Strasser was “God Himself,” arbiter of the airship universe, while Eckener was “the Pope,” “God’s” faithful lieutenant on earth.

Both men knew that bombing England was easier said than done. First, there was the weather. Eckener told Strasser that accurate weather prediction was the key to successful zeppelin operations. Heeding his friend’s advice, Strasser established a string of meteorological stations along the North Sea coast. Every three hours weather reports would be funneled into a central relay station at Wilhelmshafen for distribution to the various airship commands. It was a noble attempt, but the Germans were stymied by the fact that European weather comes in from the west, and originates in turbulent North Atlantic waters. There was simply no way of accurately predicting storms or any other phenomena.

Airship Flight Fraught With Challenge And Risk

Then, too, navigational methods were crude, based more on intuition than instrumentation. The zeppelin was a majestic “beast,” but flying an airship was a complicated art that demanded a high degree of knowledge, sophistication, and sheer nerve. An airship consisted of a series of hydrogen-filled gas cells contained within a rigid aluminum “skeleton,” the whole covered by a cotton fabric skin. Temperature variations often meant changes in the vessel’s lift. The hydrogen might expand or contract at various altitudes and temperatures, affecting not only lift but trim—that is, the vessel’s ability to stay level and on an even keel.

Strasser was aware of the difficulties and took steps to ensure successful missions. Timing was of the essence; raids were going to be conducted at night, under the cover of darkness. As an added precaution, raids were scheduled during the dark of the moon, a period from eight days before the new moon to eight days after.

On January 13, 1915, four airships took off for the first zeppelin raid on England. The mission proved abortive, frustrated by heavy fog and rain. A few days later, on January 19, the L-3, L-4, and L-6 lifted off for England. Strasser himself was aboard L-6, but a broken crankshaft on her port engine—mechanical failures were all too frequent—forced her back to base. The L-3 and L-4 continued, their objective the strategic dockyards at the mouth of the Humber River.

Buffeted by bad weather, the zeppelins drifted farther south than originally intended. The L-4 ended up dropping its bombs on some scattered English villages, while the L-3 finally appeared over the port of Great Yarmouth. German bombs rained down on the town square, destroying several small buildings in the process. Four Britons were killed and 16 injured in the raid, but overall the damage was negligible.

It was an inauspicious beginning, but Strasser was undeterred. More raids followed as the year wore on, yet the results were decidedly mixed. On June 15, 1915, Kapitanleutnant Klaus Hirsch guided the zeppelin L-10 over northeastern England. It became one of the most successful raids to date, with Hirsch managing to bomb Wallsend’s Engineering Works on the Tyne, the Palmer Works at Jarrow, Cookson’s Antimony Works and Pochin’s Chemical Works at Willington. Seventeen workers were killed and 72 injured, and vital war work disrupted.

More often, though, it was a case of the “blind leading the blind.” There was no way of measuring the strength and direction of the wind, so errors of drift were commonplace. Position was determined by dead reckoning, a notoriously inefficient method that could lead to disaster, but airship captains had little choice. Zeppelins got their bearing by visual observation, and in the early months of the war well-lit English towns could be seen for miles. After blackouts were established, airship navigation became more difficult than ever.

Blindly Dropping Bombs On Maldon

The zeppelin raid of April 15, 1915 provides a good illustration of the challenges the Germans faced. Lieutenant Horst Treusch von Buttlar-Brandenfels was a Hessian baron, an aristocrat from the top of his head to his well polished boots. Dashing and devil-may-care, Buttlar commanded the L-6, and he was determined to fulfill his mission. Unfortunately, the blue-blooded baron was lost, and as he pored over charts and peered vainly into the darkness his cause looked hopeless indeed.

The L-6 groped on, but then some lights could be seen below, bright beacons of salvation. It was an English city, but which one? Searchlights sprang to life, locking the airship in their luminous embrace. Antiaircraft fire opened up, and a shell ripped open three of the ship’s gas cells. No fires were ignited, but it was plain the ship could not continue on this course. Buttlar-Brandenfels was no coward, but discretion is the better part of valor. “Bombs away!” he shouted, and a load of 110-pound explosives was quickly jettisoned on the city below.

Not waiting to see the results, Buttlar-Brandenfels ordered a 180-degree turn at full throttle. The L-6 managed to reach base safely, but the baron was on the horns of a dilemma. His official report demanded that his target be precisely named, but the 26-year-old officer didn’t have a clue. Buttlar-Brandenfels was having a quiet drink, still puzzling over his problem, when an orderly brought him a newspaper. Scanning the print, he noticed a small article gleaned from a Dutch newspaper report. It seemed that German airships had bombed the English town of Maldon in Essex.

Eureka! Now he knew where he had been, and gratefully completed his report. The resourceful—and lucky—young airshipman was commended for “the accurate navigation of the airship and the praiseworthy choice of a key objective.”

In the meantime the Kaiser finally permitted the bombing of London, though with strings attached. Targets were to be restricted to areas east of the Tower of London; the historic heart of the great city was still off limits. Wilhelm would gradually ease these restrictions over time, but insisted that historic buildings not be touched. It was an admirable effort at “civilized war,” but the crude bombsights of the period—not to mention the haphazard navigational tools—did not permit such pinpoint accuracy.

For all of Strasser’s herculean efforts it was an army zeppelin, not a navy one, that became the first airship to bomb the British capital. On May 31, 1915, Captain Erich Linnarz piloted the LZ38 over London. The LZ38 was a typical German zeppelin of the period, measuring 536 feet (163.37 meters) from nose to tail. The cigar-shaped craft was 61 feet in diameter, with a hydrogen gas volume of 1,126,000 cubic feet. The zeppelin was powered by four 210hp Maybach engines which could propel the craft at 60mph (96km/h).

The LZ38 had achieved complete surprise, and Linnarz later recalled that “London was all lit up—Not a searchlight or antiaircraft gun was aimed at us before the first bomb was dropped.” The LZ38 managed to unleash its full payload of 150 bombs and incendiaries before making good its escape. Damage was said to be relatively light, but 42 people were killed or wounded in the raid.

The British Public Grows Weary of German Air Attacks

The British public became more and more disenchanted with the military’s seeming helplessness in the face of the German onslaught. The Royal Flying Corps could only grind their teeth in impotent rage, because no matter how they tried, they seemed unable to down one of the silvery leviathans. True, Flight Sub Lieutenant Reginald A.J. Warneford brought down the LZ37 over Ghent, Belgium on June 7, 1915, by flying above the airship and literally dropping bombs on it. The RNAS pilot had won a well-deserved VC (Victoria Cross) for the exploit, but luck had been with him.

In raid after raid the airships returned safely to base. Shells tore gaping holes into gas cells, and bullets tattooed punctures in their outer skins, but with no effect.

Although it has a reputation as a highly inflammable gas, hydrogen alone does not burn, and is only dangerous when mixed with oxygen. It was a fact that continued to confound the British as they desperately sought a means to combat the zeppelin menace.

The stage was soon set for one of the most successful airship raids of the war. In spite of its official number, the L-13 was lucky to be piloted by a brilliant commander. Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Mathy was a superb strategist with a genuine talent for zeppelins. Cool, courageous, deliberate, Mathy grew to be a legend in his own time, a man whom friends and enemies alike agreed was the greatest airship captain of the war.

The L-13 flew to Cambridge, about 60 miles north of London, to use the famed university town as a staging area. At 7,000 feet London could be seen in the distance, the great metropolis of the British empire a pulsating aurora of beckoning lights. By about 11:30 pm. Mathy was soaring over London’s northwestern suburbs, heading for the heart of the city. He had visited London in 1909, so he was familiar with its layout. Peering intently from his control car gondola, the airship captain could see landmarks like the Houses of Parliament and St. Paul’s Cathedral spread like a three-dimensional map at his feet.

“First bombs away!” Mathy cried, and the first of some four thousand explosives on board took to the air. The first victim was one Henry Coombs, who was killed while standing in a passageway just off Theobald’s Road near the British Museum. More bombs detonated, destroying a block of flats at Portpool Lane. British searchlights came to life, spiking the pitch-black sky with their probing beams. They finally found the L-13, their fingers of light caressing the airship’s sleek sides and providing a target for the antiaircraft batteries below.

Dropping Payloads On London

The 26 antiaircraft batteries that dotted the city opened fire with a throbbing, thundering roar, peppering the air with shrapnel and incendiary shells. One of Mathy’s crewmen aboard the L-13 later remembered that the shells came close, “very close.” Ragged mushrooms of blue-white smoke burst all around the giant airship, the near misses causing another crewman to nervously shout, “Let’s get out of here!” Mathy was not about to be rushed, and continued coolly circling the city until all his bombs were dropped. The kapitanleutant carried a 660-pound bomb he intended to drop on the venerable Bank of England. The monster explosive missed its intended target, but the smoke, flame, and obvious damage it created gave Mathy great satisfaction. Satisfied at last, Mathy ordered the L-13 to ascend from its current 8,500 feet to 11,200 feet, a command the crew greeted with obvious relief. The L-13 dropped its last bombs on the Liverpool Street Station, scoring a direct hit on two London buses that killed 15 people.

The zeppelin headed for home, leaving a swath of death and destruction in its wake. Fires were raging in warehouses near St. Paul’s Cathedral, adding to the night’s grim tally. In a mere 15 minutes a single zeppelin had killed 32 people and caused damage that amounted to 530,787 pounds (about $2.5 million). By October 1915, when bad weather called a halt to zeppelin operations, the British could pause and take stock.

There had been 22 raids on England all told, which inflicted casualties of 208 killed, 530 wounded, and some 800,000 pounds of property damage.

The raids had revealed serious flaws in the British home defense system. Airplanes had trouble flying at night, and even when they could locate an airship, their bullets were ineffective. Some British artillery was actually more lethal to British civilians than to the enemy. One-pounder “pom-poms” lacked time fuses, and so would sometimes fall to earth and explode in houses and streets. People would often come outside to see the giant behemoths overhead, only to fall victim to “friendly” fire. Also, at least at first, the British seemed reluctant to establish complete blackouts.

The Germans were also having problems; in one year 21 zeppelins had been lost due to various causes, a sobering statistic indeed. Yet Strasser and airship captains like Mathy insisted the benefits outweighed the disadvantages, at least when considering the air campaign against England. British morale might be seriously shaken by the raids, and even if the stubborn islanders did not sue for peace, they would be forced to maintain huge defense forces at home—forces that otherwise might be sent to France.

The spring of 1916 saw the beginning of a new German airship offensive against England. British defenses had improved; total blackouts made navigation that much more difficult. New and better artillery made raids at lot more hazardous than they had been in 1915, and there were now airplanes capable of reaching zeppelin altitudes, even if night flying was still a near-suicidal enterprise.

New Class Of Zeppelin Takes To Skies

In May 1916, the Naval Airship Division took delivery of the L-30, first of a new class of improved zeppelins that seemed to promise victory. The L-30 was an impressive 650 feet long, 90 feet high, and its gargantuan frame could hold about two million cubic feet of hydrogen gas. Its six Maybach engines, while powerful, could deliver a maximum speed of 65 mph, only a slight improvement over older designs. Combat ceiling—and that included a maximum payload of five tons of bombs—reached 13,000 feet. The L-30 would be well protected by no fewer than 10 machines guns posted at various points along the ship.

The September 2-3, 1916 raid was going to be the largest of the war, a joint effort by the army and navy. Twelve navy airships would participate, including L-11, L-13, L-14, L-16, L-17, L-21, L-22, L-23, L-24, L-30, L-32, and SL-8. Four army airships were going to join the raid, including the LZ90, LZ97, LZ98, and SL-11. The 16 airships carried a combined total of 32 tons of bombs.

The SL ships were not technically zeppelins, but airships built by the rival Luftfahrzeugbau Schutte-Lanz Company. The Schutte-Lanz airships featured a cleaner aerodynamic shape, cruciform tail fins with rudders and elevators for improved steering. Unfortunately, SLs featured a “skeleton” framework made out of plywood, not aluminum. In high humidity, or in fog or rain, the wood tended to absorb moisture, making the ship heavy and putting strain on the glued joints. Strasser never liked them, derisively calling their proponents “the glue potters.”

Army Zeppelin LZ98, commanded by Ernst Lehmann, approached London from the southwest, intending to drop his load of bombs on the dockyards that lined the Thames. Antiaircraft batteries at Dartford and Tilbury spotted LZ98 and opened fire, dirty white blossoms of flame-tinged smoke marking near misses.

Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson was also in the area, nursing his BE-2C to ever-greater heights as he searched for airships. His plane’s four-bladed propeller corkscrewed through the darkness as Robinson climbed to 12,300 feet. A chill wind whistled though the BE-2C’s open cockpit, but the lieutenant was so intent on his quarry he scarcely took notice.

Robinson’s Lewis gun was loaded with the recently developed explosive and incendiary ammunition. Beside “Pomeroy” and “Brock” bullets, there was also “Buckingham” ammunition, which was a phosphorus incendiary bullet. Used individually, these bullets brought mixed results, but used in tandem they proved a lethal combination for airships. The explosive Pomeroy and Brock ammunition blew holes in an airship’s gas cells, allowing hydrogen to leak out and mix with the oxygen in the atmosphere. The Buckingham incendiaries would follow in sequence, igniting the mixed gases and causing fires to start.

The “mixed ammo” sequence proved a winning combination in Britain’s airship struggle. There were some risks involved; sometimes incendiary bullets would go off prematurely, exploding in the machine gun and leaving the pilot with painful, even serious, face burns. Right now, though, Robinson was too intent on tracking down an airship to care much about personal safety. The young RFC officer could see nothing, and the deafening clatter of his own motor prevented him from hearing an airship’s approach. Robinson opted for a risky maneuver—he cut his own engine in mid-flight, the better to catch the telltale drone of Maybach engines.

The ploy was unsuccessful, and cutting the motor meant a loss of hard-won altitude. He switched his engine back on, and then he saw it—the LZ98—just now dropping bombs like a giant bird laying eggs. Robinson attacked at once, but apparently he was spotted in time. The LZ98 started to gain altitude, its Maybach engines throttled to 60 mph. Lieutenant Lehmann sought and found cloud cover, then proceeded northeast. Robinson was furious; the zeppelin was well beyond his plane’s operational ceiling of 13,000 feet. He had pushed his little biplane almost to its limits—around 12,900 feet—and had nothing to show for it.

A large white object materialized below, its sudden appearance and huge bulk giving it a dreamlike, almost spectral quality. It was the SL-11, commanded by the ironically London-born Wilhelm Schramm. Reaching the British capital at about 1:00 am, the SL-11 unloaded its bombs on the suburbs of the great metropolis. Like most airships, the SL-11 was a mesmerizing sight, a six-hundred-foot “whale” swimming in an ocean of air currents with a slow but steady grace. The RFC lieutenant could see the antiaircraft bursts that played all along the great ship’s hull, but so far there had been no hits and no damage sustained.

Robinson attacked, but suddenly the airship disappeared from view. How could a six hundred-foot-long monster vanish without a trace? “Of all the rotten luck!” Robinson said to himself, the bitter words disappearing into the plane’s rushing slipstream. Refusing to admit defeat, Robinson searched for another 20 minutes or so. At 1:52 am, the determined RFC pilot was rewarded for his patience and persistence. He could see a reddish glow to the northeast, a telltale sign of fires ignited by German bombs. An airship was unloading its deadly cargo, revealing its presence by the ground explosions and fires.

Sure enough, Robinson spotted the massive bulk of an airship as its nose poked out of some clouds. It was the SL-11, the same airship that had earlier eluded him. Now there would be no escape. But before he could begin attacking, a shell exploded right beneath him, the resulting shock wave creating a freewheeling turbulence that tumbled his BE-2C like a windblown leaf. It was “friendly” fire from down below; antiaircraft batteries were intent on shooting down the airship and couldn’t see Robinson’s tiny, black-painted biplane.

A Battle of David Against Goliath

Recovering, Robinson saw the bulbous nose of the SL-11 as it approached him head on. It was David against Goliath, but luck was with him; the SL-11 had machine gunners, but they had yet to detect his presence. The airship crew was still too preoccupied with their bombing run, which continued. Robinson flew under the SL-11, drilling its underbelly with a whole drum of explosive and incendiary bullets. The entire length of the airship had been punctured, but the leviathan sailed on, seemingly oblivious to the numerous “pinpricks.”

Robinson tried again, his Lewis gun chattering as a steady stream of Pomeroy and Brock ammunition peppered the airship hull, but there was still no effect. Gunners aboard the SL-11 replied in kind, but Robinson managed to evade their defensive bursts. The RFC pilot decided to concentrate his fire on one section of the hull. Soon a tiny glow flickered tentatively inside the airship’s hull, growing brighter and brighter with each passing moment. Then long tongues of flame appeared, greedily consuming the ships outer envelope.

The SL-11 began its death plunge, an incandescent streak marking its blazing passage to earth like a man-made meteor. It crashed at Cuffley, just north of London, in some open ground behind a pub. It continued to blaze for two more hours. The 16-man crew were incinerated, charred beyond recognition by the searing heat. SL-11’s fiery demise could be seen for miles, provoking a surge of relief and patriotism from British citizens far and wide. Cheers broke out, and one group even spontaneously sang the anthem Hope and Glory. Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson was awarded the coveted Victoria Cross for his actions.

Three weeks later the L-33 was forced down near the village of Wigborough in Essex, its gas cells severely damaged by a shell. kapitanleutant Alois Bockner and his crew, 22 Germans in all, were unhurt but stranded in enemy territory. Bockner led his men down a country road, a large crowd of locals gaping at the strange sight— the only armed German “invasion” of World War I. When a local constable on his bicycle challenged the intruders, they meekly followed him into captivity.

The L-32 was also lost, and under more tragic circumstances. Lieutenant Frederick Sowry of the Home Defence Wing was flying his BE-2C, serial number 4112, when he came upon the giant airship and pumped two drums of Brock-Pomeroy ammunition into it. Like the SL-11, L-32 became a giant torch that illuminated the night sky. There were no survivors. German morale began to plummet as losses mounted. Euphoria was replaced by a growing sense of doom. Death was no longer a possibility; it was a virtual certainty. Crewmen aboard stricken zeppelins had few options, because airships did not carry parachutes. Some men preferred jumping to their deaths, which was relatively quick, to the protracted agony of being burned to death. When airship crews called themselves “himmelfahrtkommandos,” or “suicide squads,” it was with a sense of reality, not bravado.

A quartermaster’s mate aboard the L-31 confessed to a friend that “I dream constantly of falling zeppelins. There is something in me I cannot describe. It is as though there was a strange tunnel of darkness before me into which I am compelled to go.” Another German airshipman confessed that “it is only a question of time before we will join those who have perished before us.” Even Hendrich Mathy was pessimistic, feeling that his days were numbered. These premonitions proved all too tragically accurate.

On October 1, 1916, Mathy’s L-31 was shot down in flames near Cuffley, where the SL-11 had also met its end. With Mathy’s death the “soul of the airship service” also expired. But it still had a heart, Peter Strasser, who refused to believe that zeppelins were becoming obsolete as strategic bombers.

Strasser was now a Fregatenkapitan, the equivalent of a rear admiral, and had been awarded the Por le Merite decoration, the fabled “Blue Max.” Strasser pinned his hopes on yet another new kind of zeppelin, the height climber. These special airships could operate at altitudes of 16,000 feet, and could even go as high as 20,000 feet. This was high above the operation ceiling of most British fighters of that time, about 13,000 feet.

The high climbers neutralized British defenses—but there was a high price to be paid for such seeming success. The air was thin in the substratosphere, and bitterly cold. Altitude sickness became a problem, as well as lack of oxygen. Frostbite was common, because gondolas were unheated to save weight. Crewmen stuffed newspapers into flying suits in a vain effort to keep warm, a futile gesture in the face of temperatures that could dip to -20F or even -27F.

Zeppelins were now so high cloud banks were below them, obscuring visual navigation. Radio beams were unreliable as a navigation tool, and severe weather encountered in the substratosphere buffeted airships unmercifully, causing even greater errors of drift.

Worse still—at least from the German point of view—British technology caught up with the height climbers. On the afternoon of August 5, 1918, six height-climber zeppelins embarked on what became the last airship raid of the war. Strasser himself was aboard the L-70, the newest and fastest zeppelin of the Naval Air Division, confident no British plane could reach him.

The End Of An Era Marked With Flames

It was a fatally wrong assumption. Three British planes were in hot pursuit, including a DH4 two-seater whose 375hp Rolls-Royce engine enabled it to fly at 22,000 feet. The DH4 was piloted by Major Egbert Cadbury (of the chocolate family), his gunner/observer Captain Robert Leckie. The L-70 was soon in range, and Leckie opened fire with his Lewis machine gun. The zeppelin was consumed by flames in less than a minute.

The death of Fregatenkapitan Strasser marked the end of the German airship campaign against Britain. The army had discontinued raids after the loss of the SL-11 in 1916, but Strasser had refused to admit defeat. His obsession with airships had become fanaticism in the end, a fanaticism that ignored horrific losses and ultimately cost him his life.

In retrospect, the Germans had committed a grave strategic error by concentrating their bombing effort on London. The capital city was the great magnet, its enormous political significance as the heart of the British empire exerting a powerful influence in German strategic planning. Even if they couldn’t inflict much material damage, Fuhrer des Luftschiff Strasser hoped bombing London would affect British morale. But British morale, although initially shaken, actually grew stronger as time passed. Zeppelins became known as—ironically, in view of the Kaiser’s qualms—“baby killers.” The bombing became an effective anti-German propaganda tool for recruitment.

By concentrating on London, the Germans inadvertently spared much of the industrial Midlands and the North, regions vital to the war effort. It was a major tactical error, a mistake that would be repeated by Hitler’s Luftwaffe in World War II. Britain’s Royal Air Force was on the verge of defeat in 1940, its airfields bombed out, its personnel near exhaustion, when the Germans switched to attacking London and gave the RAF a welcome respite.

The one thing the airship campaign did do was to tie up forces that could have been employed elsewhere. By the end of 1916 no fewer than 12 Royal Flying Corps squadrons were employed in home defense, and “the antiaircraft guns were served by 12,000 officers and men who could have found a ready place with continuous work in France or other theaters.”

Great story, and one that really needed telling. Thanks!