By Kevin Hymel

Everywhere General George S. Patton, Jr., went, from North Africa to Sicily to continental Europe, his camera swayed from his neck, ready to capture images that interested him. The camera, a German-made, 35mm Leica with “G.S.P. Jr.” emblazoned in gold, recorded Patton’s life at war as well as his armies’ campaigns.

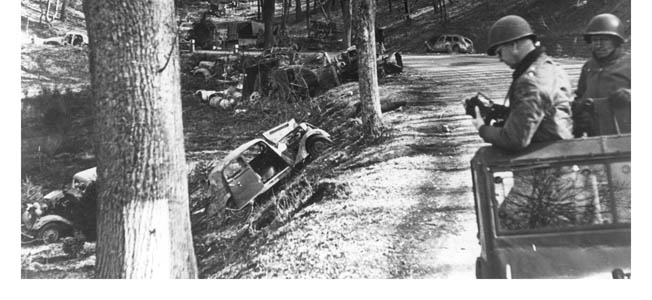

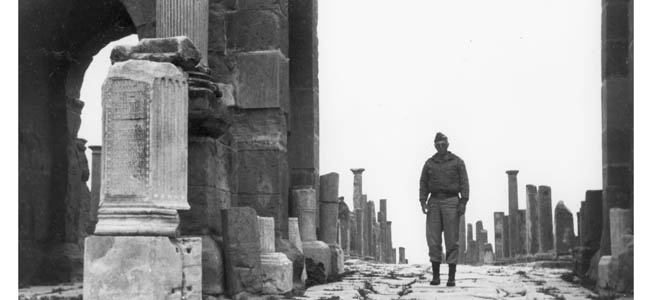

Patton’s pictures show the victorious face of war: American GIs on the move, Sherman tanks with hedgerow cutters welded to their hulls, and military bridges being built. They also show defeat: smashed German tanks, hapless prisoners of war, and dead bodies strewn across the landscape. Along with pictures of modern war, Patton took shots of historic sights and the different terrains of his battlefields from North Africa to Germany.

The general’s picture taking added to his colorful legend. In Sicily, he claimed his hobby prevented his death. During the race to Messina, he got out of his command car to take a photo of a town when a salvo of German shells exploded up the road. The photograph, he wrote, “saved my life.” Toward the end of the war, when a Spitfire pilot mistook Patton’s Piper Cub light aircraft for a German Fieseler Storch and strafed it three times over Germany, Patton took out his camera and photographed the action. Unfortunately, “I found I had been so nervous I had forgotten to take the cover off the lens and all I got were blanks,” he wrote.

Every chance Patton got, he sent his photographs to his wife, Beatrice. Included with his own were U.S. Army Signal Corps photos and pictures of himself taken by others. After the war, she organized the pictures as best she could into photo albums, eventually filling 11 books. If her husband had written on the back of a photo, she transcribed the caption onto the album page. Today, the albums are stored with the Patton Papers in the Manuscript Room of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. The collection includes six boxes of negatives and other photographs. Shown here is a sample of the collection.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments