By Phil Zimmer

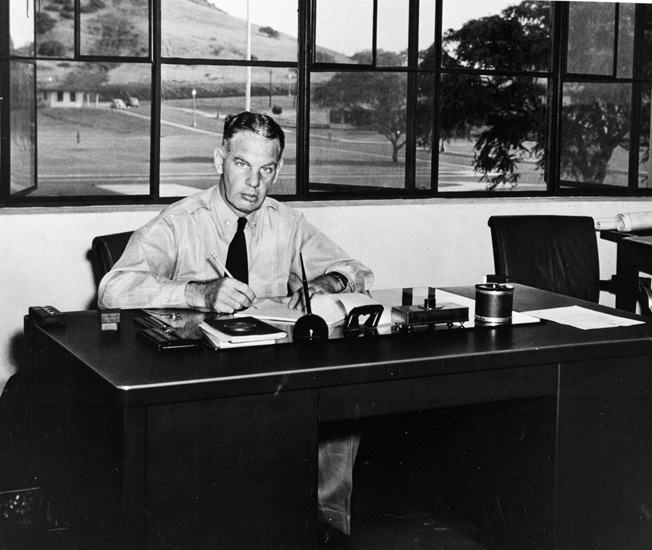

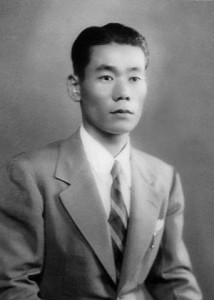

“You are probably the nearest to war that you’ll ever be without actually being in it,” said Commander Harold M. “Beauty” Martin as he addressed his men on the morning of December 6, 1941, at Kaneohe Naval Air Station on Mokapu Peninsula, located less than 15 miles east-northeast of Pearl Harbor. “Keep your eyes and ears open and be on the alert to every moment,” said the well-respected commander. One fellow who was keeping his eyes wide open that day was Japanese spy Takeo Yoshikawa. He closely observed the Pacific Fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor on the south side of Oahu late in the afternoon from vantage points at Aiea Heights and the Pearl City Landing. Later the same day, he sent a coded report to Tokyo noting that the U.S. Army had ordered equipment for barrage defense balloons, but none was yet on scene, and he opined that torpedo nets probably were not in place to protect the battleships at anchor in Pearl Harbor. “I imagine that there is considerable opportunity left … for a surprise attack,” he added, as the clock continued ticking.

Meanwhile, Commander Martin’s somber, cautionary message earlier in the day was being widely debated by the American sailors, a number of whom belittled the racial and intellectual capabilities of the Japanese, especially their ability to handle fast-moving aircraft. Some even argued that any aggressive Japanese actions against the United States would be quashed within two weeks.

But within 24 hours those men and their American compatriots at Pearl Harbor would be in the fight of their lives against two waves of incoming Japanese bombers and fighters. Within 90 minutes of the first attack early on December 7, the Japanese had sunk four battleships and damaged another four of the large ships, three cruisers, and three destroyers and consigned nearly 200 American aircraft to the scrapyard. Worse yet, more than 2,400 Americans were killed and more than 1,175 wounded in the surprise attack. (A pair of amateur filmmakers captured the fateful events of December 7 with their 8mm movie camera. Read all about their recording of the Pearl Harbor Attack.)

The First to Face the Enemy: Raid on Kaneohe Naval Air Station

Those at the Kaneohe Naval Air Station were among the first to face the enemy onslaught that Sunday morning. The nimble Mitsubishi A6M Zeros came in at 7:48 am, strafing a small utility plane and fanning out over the station and firing promiscuously. The officer on duty called nearby Bellows Field requesting help, but his message was treated as a joke. Kaneohe contractor Sam Aweau called both Bellows and Hickam airfields, but his warnings also were met with disbelief.

Commander Martin, for his part, was gulping a cup of coffee in his quarters and preparing hot chocolate for his 13-year-old son when the youth reported seeing the Japanese planes maneuvering above. Once Martin spotted the Rising Sun emblem for himself, he quickly tossed his uniform on over his blue silk pajamas and dashed for the car. Screeching through the still-quiet residential neighborhood at upward of 50 miles per hour, Martin managed to park near his command post and run toward it amid a hail of bullets.

The first parked plane was already in flames when Martin arrived at Kaneohe, and soon the Japanese bombers joined the fray. He was proud of how his men responded, many of whom were newcomers to the service. “There was no panic,” he said. “Everyone went right to work battling back and doing his job.”

Unfortunately, Kaneohe had no antiaircraft guns. Sailors and marines fired their pistols and rifles at the low-flying aircraft without success. Once the first wave of attackers disappeared, the men dashed to the hangars and planes. The ordnance staffers began issuing rifles and machine guns and disbursing ammunition from locked storage areas.

Aviation Chief Ordnanceman John W. Finn positioned both a .30-caliber and a .50-caliber machine gun on the parking ramp for the Consolidated PBY Catalinas (PBY) and began dueling with the Japanese Zeros as they strafed Kaneohe. Finn moved back and forth between the two weapons, but he spent most of his time at the .50 caliber. As he fired, he was assisted by sailors who replenished his ammunition. Finn’s steady firing damaged several Zeros. No one knows for sure whether it was Finn or someone else, perhaps an ordnanceman named Sands, who fired the rounds that struck flight leader Lieutenant Fusata Iida’s aircraft.

The nine Zeros led by Iida were beginning to reassemble to head back to the carrier fleet when Iida motioned to his wingman that he had sustained damage to his fuel tanks and would not be able to make the return flight. He therefore decided to make a kamikaze run on Kaneohe’s armory. As he lined up and flew toward the armory, more ground fire struck his aircraft. The plane missed the armory and crashed into the ground.

By the time the fighting was finished at Kaneohe, the Japanese had destroyed or damaged 33 PBYs, killed 19 servicemen, and caused major damage to the installation. Despite the great risk they took, the Japanese suffered few losses in the audacious attack against the home of the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

Takeo Yoshikawa: Japanese Spy at Pearl Harbor

Much of the credit goes to spies like Yoshikawa, a youngish looking naval reserve ensign who had only arrived in Hawaii nine months earlier. He was employed as a cover by the Japanese foreign ministry using an alias while actually working for the Imperial Japanese Navy. He had been providing continuous and rather thorough updates on U.S. Navy deployments, arrivals and departures from Pearl Harbor, centerpiece of U.S. naval operations in the Pacific. Takeo Yoshikawa was scrupulously careful, carrying no camera, maps, or documents with him and never jotting down notes on what he observed on his outings around Hawaii.

In many ways, Yoshikawa was the perfect man for the mission. He had a solid naval background, having graduated in 1933 from the Japanese Naval College as well as from torpedo, gunnery, and aviation programs in the Imperial Japanese Navy. He also had served as a code officer aboard a cruiser. He then had worked three years in Tokyo with the Imperial Japanese Navy’s British affairs section before expressing an interest in working abroad as an agent. That led to his assignment in Hawaii working for Japan’s foreign ministry as a cover.

Yoshikawa did not have diplomatic immunity, and he was not officially linked to the Imperial Japanese Navy when he arrived in Hawaii. Otherwise, he would have been known to the American counterintelligence officials nearly immediately. Only Nagao Kita, the new consul in Hawaii, and Vice Consul Okuda, who had done some prior spying in Hawaii, were aware of Yoshikawa’s true role in providing Japan with updates on the U.S. Navy.

Turning Against America: Yeoman First Class Harry T. Thompson

American security had tightened before Takeo Yoshikawa’s arrival, in part due to deteriorating relations between the two countries. The deteriorating relations were a result of Japan’s continued aggression in China and concerns about future potential moves against such Western interests as Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, and the oil-rich Dutch East Indies.

Two Japanese spying incidents on the American mainland in the 1930s had put the United States on alert. One involved former Navy Yeoman First Class Harry T. Thompson who had been discharged from service for problems relating to alcohol, overspending, and “an appetite for attractive young men,” according to one source. His services were retained by the Japanese, and he used a chief yeoman’s dress uniform, purchased at a tailor shop near a base, to gain entry to American bases and ships, thanks to his uniform, lax security, and fast talking. He managed to obtain gunnery manuals and reports on the 8-inch guns carried by the USS Pensacola, the first of a new class of cruisers capable of 32 knots and costing Japan its previous technical advantages in the cruiser category.

Toward the end of 1934 Thompson was able to board a number of ships stateside where he obtained important quarterly schedules of employment for battleships and cruisers, as well as information on main batteries, torpedoes, and related intelligence. He boarded the USS Mississippi in December and managed to abscond with a 230-page U.S. Navy gunnery school publication from a confidential file. He reboarded the ship the next month and purloined reports on the main gun batteries and torpedoes.

His former live-in boyfriend exposed Thompson’s homosexuality to Navy officials. Officials followed Thompson for a while, gathered additional evidence, and questioned him about his suspicious activities. At that point, Thompson confessed to working as a spy for the Japanese. When efforts by the Office of Naval Intelligence to have Thompson cooperate as a counterspy failed, he fled using funds supplied by the Japanese. He was apprehended and in mid-1936 was found guilty of espionage and sentenced to 15 years in federal prison.

John S. Farnsworth: Japanese Spy in the Naval Academy

Even more troublesome for U.S. officials and perhaps the American public was the case involving John S. Farnsworth, a 1915 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy who had been selected for postgraduate work at Annapolis as well as postgraduate work in aeronautical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He had commanded Marine Observation Squadron Six, Aircraft Squadrons’ Scouting Fleet, before being relieved of command in 1927 and court-martialed. He was cited for drinking, gambling, and borrowing money from an enlisted man and refusing to pay it back as well as submitting falsified affidavits regarding the matter.

That resulted in a six-year downward spiral of drinking that led to his spying for the Japanese using an American-owned business as cover. His efforts to obtain classified aeronautical information caused suspicion among the tight-knit community of Naval Academy graduates who ran the U.S. Navy in the prewar years, especially because of his earlier court-martial. The head of naval intelligence got wind of Farnsworth’s snooping efforts and sent a cautionary bulletin out, effectively cutting him off from information that would prove useful to Japanese intelligence.

Farnsworth’s drinking increased substantially, and he became more desperate as his money problems escalated to the point where he appeared at his former business partner’s Washington office in an effort to get a place to sleep. In mid-1936 he contacted a Hearst-owned news service with a scheme to sell his tell-all story for $20,000 while he was also working his Japanese contacts to obtain another $50,000 for past and future services.

Both the Office of Naval Intelligence and the FBI were on his tail by then and he was picked up on July 13. He signed a confession admitting to some of his espionage and was found guilty and sentenced to four to 12 years in federal prison. His Japanese contacts were conveniently out of the country, having been transferred home.

Why Japan Shifted Toward Homegrown Spies

Despite increased American security measures, the Japanese continued efforts to obtain information both on the American defense industry and bases in the continental United States and Hawaii. It was probably because of the Japanese military’s experiences with Farnsworth and Thompson that they began to rely more heavily on homegrown spies like Yoshikawa.

Yoshikawa, for his part, was exceptionally security conscious. In sallying forth from the consulate, he dressed casually and conscientiously refrained, for the most part, while associating with Japanese Americans, with the exception of his two trusted drivers. They drove him around Oahu in their personal vehicles rather than in consulate cars to avoid unwanted attention.

The drivers, especially Richard M. Kotoshirodo, who had been born in Hawaii and who had received his early education in Japan, proved exceptionally reliable. Kotoshirodo was coached by Yoshikawa so he was able to correctly identify ships by their silhouettes and conduct surveillance by himself. This effectively added another set of skilled and trustworthy eyes to his spying effort.

Takeo Yoshikawa’s Views of the Harbor

One of their favorite haunts became the Pan American Clipper Landing at Pearl City near the moorings for the U.S. carriers. Yoshikawa also liked to visit Eto’s Soda Stand adjacent to the Pearl City Landing, a popular transit point for Ford Island and ships’ personnel going or returning from leave. He and his drivers arrived at the landing dressed as workmen and blended with the workers to pick up tidbits of useful information and observe work in the East Lock where the aircraft carriers were provisioned and fueled. They also counted the number of vegetable trucks at the landing to determine the projected upcoming timing of departures for maneuvers and the length of time planned at sea.

They also went to Aiea Heights, located just north of the harbor, for a panoramic view of the area. From this vantage point, they were able to monitor all of the U.S. naval and aircraft assets in Pearl Harbor.

Yoshikawa often took in the view from the Shuncho Ro Japanese Teahouse on the heights that conveniently had a second-floor telescope for viewing the harbor. And the teahouse was owned by a friendly Japanese woman born in the same region as the intrepid spy. Yoshikawa also befriended a waitress there who he often brought along to provide cover while on espionage trips around the island.

He even took a sightseeing flight in the early fall over Oahu, bringing a geisha along as cover. While the flight was not permitted over Pearl Harbor, he was able to tally the airplanes and hangars at Wheeler and Hickam airfields, and see the battleship anchorages. He was also able to calculate air turbulences and currents along the route, which was crucial information for the Japanese pilots who would participate in the attack.

He found that Hickam Field, located just southeast of Ford Island, was difficult to observe from afar. He solved that by attending an August 6 open house to observe the Curtiss P-40 Warhawks on the ground and in the air. He took note of the hangars and the length and width of the multiple runways at Hickam Field.

Commander Martin’s air station at Kaneohe also drew Yoshikawa’s attention with its PBY reconnaissance aircraft and recent construction work there. He took a number of commercial tourist boat trips around Kaneohe and used a nearby elevated roadway for an additional view of the base.

Bernard Otto Kuehn: An Asset From Nazi Germany

Yoshikawa’s increasing and detailed reports proved exceptionally useful to his employers in Japan, who had also developed a stay-behind agent in Hawaii named Bernard Otto Kuehn. A German national who arrived in Hawaii in 1935, Kuehn was already employed as a spy for Nazi Germany. Although initially believed too nervous for the assignment, the Japanese did bring him on board in the late 1930s, providing him with a small radio transmitter with a range of 100 miles. He was to use it to relay messages on ship movements and construction to Japanese submarines which, in turn, would relay them to Tokyo.

It was vital that he remain well below the radar of American intelligence officials, but his spending habits, lack of employment, and careless pro-Nazi comments had brought him to the attention of the Office of Naval Intelligence. His wife’s early 1940 trip to Japan to obtain bank funds in $500 bills and his family’s flashing of crisp, new $100 bills raised eyebrows as did using cash to pay off a second mortgage on one of his houses.

The Kuehn family seemed oblivious to the need for stealth. His daughter Ruth worked as a modest hairdresser, but she paid her bills with large denomination currency. She also compared her success in collecting contributions to a local charity to her previous experience raising funds for Hitler in Germany. And the supposed need for additional family funds prompted the hapless spy to make at least three direct visits to the Japanese consulate to make a plea for funds.

Guilty of Espionage

Interestingly, Yoshikawa was activated on October 2 when he was sent directly to the Kuehn house to deliver $14,000 in new Federal Reserve bills along with a note that Kuehn was to test his radio transmitter. The German passed a note back to Yoshikawa saying he was unable to make the test.

Kuehn was hesitant to use the radio transmitter for fear that the U.S. military might discover and locate his signals. They then developed a system of rather strange visual signals that could use car headlights, lights flashed from the upper levels of his home, and symbols hung from Kuehn’s sailboat. All would necessitate a Japanese submarine sailing rather dangerously close to shore to see the signals.

The hapless German, who had been under surveillance for years, was arrested on December 7, tried in Honolulu, found guilty of espionage in February 1942, and sentenced to death by firing squad. The evidence obtained after his arrest was rather substantial and included monies given to him by Yoshikawa, extensive binders with newspaper clippings on the U.S. fleet, its bases, and aircraft, along with an array of photographs of navy ships. Kuehn’s sentence was later reduced to 50 years in prison once Yoshikawa was identified as the main spy behind the attack.

Yoshikawa, for his part, had sailed for Japan in a diplomatic exchange after the attack and well before his role was discovered during interrogations of his driver Kotoshirodo. Kuehn and his family were sent back to Germany after the war.

Japan’s successful intelligence-gathering operation on Oahu in the months leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor prompted the United States to tighten its national security efforts in the decades that followed.

Excellent and insightful article

The spies did their job well except for the failure to account for the aircraft carriers. The carriers were in port at the time of last message to Tokyo but left shortly thereafter and their absence from the harbor went unreported. Result was stopping the Japanese advance at Coral Sea and turning them back at Midway a month later.