By Phil Zimmer

Gerald “Zulu” Lewis peered from his Hurricane and spotted 20 German Bf-110s circling with a heavy escort of fast and deadly Bf-109 fighters over Redhill, south of London. It was shortly after 9 am on September 27, 1940.

Instinctively, Lewis dove down, laced a two-manned Bf-110 with two short bursts of fire from his machine guns and sent the intruder plunging earthward in a pale of smoke. Avoiding the temptation to fruitlessly follow the doomed plane down, Lewis turned back to the circling fighter bombers and used another burst from his guns to knock out the starboard engine of another Bf-110 and set it on fire.

The blond-haired South African pilot, who already had earned a Distinguished Flying Cross for his service months earlier in the skies over France, then pulled back on his control column and climbed upward toward the sun. As he reached the defensive ring of circling Bf-110s, he let loose with his eight Browning machine guns and downed his third Bf-110 for the morning.

Before day’s end, the bright-eyed Lewis would claim six enemy aircraft destroyed and two probable kills to boot. But the day included the loss of another gifted pilot, 23-year-old Flying Officer Percival Ross-Frames Burton, who had pursued a fleeing Bf-110 for some 40 miles before he ran out of ammunition and his guns fell silent. In frustration, Burton then banked his Hurricane and used a wing to deliberately sever the German plane’s tail, causing it to crash in a field in Sussex, instantly killing both the pilot and co-pilot. Burton tried in vain to maintain control of his plane before it crashed into an oak tree, instantly killing him.

That incident gave rise to the “Gone for a Burton” phrase used to describe a heroic, desperate act similar to that taken by the squadron leader.

Lewis, for his part, did not have an easy go of it that September day. On returning toward base later that afternoon, he was jumped by a Bf-109 pilot who caught him with cannon fire. With flames licking all around him, Lewis managed to pull back the cockpit cover and get out.

The ejection from the plane “caused me to be shaken around like an old rag; then there was the blissful peace and calm of falling free,” said Lewis. He managed to land relatively safely, although his legs, face, and neck were burned, and he had a third-degree burn on his trigger finger. He spent two months in a hospital, was promoted to Flying Officer in November, and survived the war.

Lewis was one of the lucky ones. Hundreds of British pilots and Luftwaffe airmen and thousands of British civilians would be killed before the Battle of Britain ended. The protracted air campaign, in which the German Luftwaffe sought to achieve air superiority over Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF), lasted roughly from July 10, 1940, to October 31, 1940. The air campaign marked the first defeat in the war for Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s forces, which previously had seized Austria and Czechoslovakia and easily overran western Poland, Denmark, and Norway before conquering France, forcing the British and remnants of the French armies from the European continent by June 1940.

Although billed by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and others as a battle of the few against the many in Britain’s “Finest Hour,” the hard-fought campaign fell somewhat short of that distinction. The battle was nearly a draw in terms of the number of planes lost. The British lost approximately 1,643 and the Germans lost approximately 1,686 aircraft during the campaign.

But it was not the heroic efforts of a few brave fighter pilots, but the combined and determined efforts of everyone on the British Isles that thwarted the German effort to subdue the island. Not only did the British Fighter Command do its duty, but the British Bomber Command and the British Royal Navy also played key roles in keeping the Germans at bay. In frustration, Hitler turned his attention eastward to the Soviet Union, a country he sought to conquer for Lebensraum; that is, additional living space, for the German people. Hitler believed the fall of the Soviet Union would ultimately force the recalcitrant British to the negotiating table.

In many ways the Battle of Britain is best viewed as a life-or-death struggle for supremacy based on men, machines, technology, and tactics. And it was the British who came out on top in all four categories. The difference was made by the women who manned the radar screens, the workmen who built the planes, those who refurbished damaged aircraft, and those who kept the sea lanes open so food and war matériel could continue to flow to the embattled British.

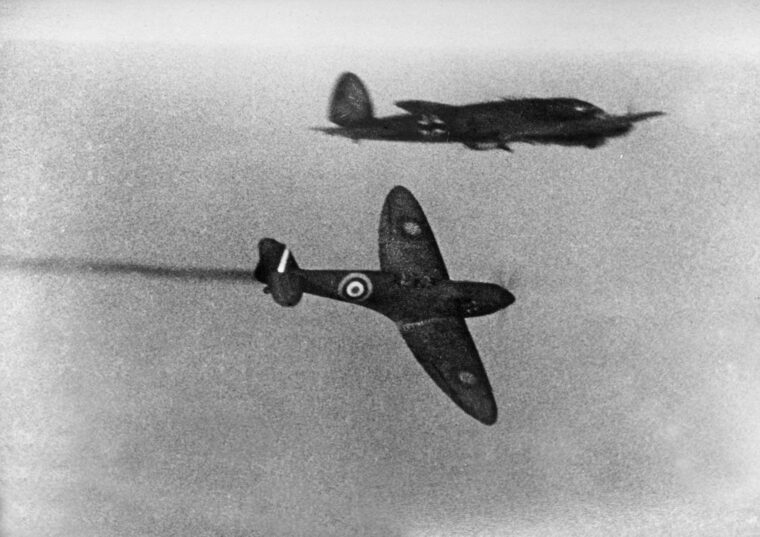

The German Bf-109 and the British Spitfire, both single-seat fighters, came to symbolize the battle. Each was a superb plane in its own right, although the Bf-109 initially had one key technological advantage. That edge was a fuel-injected engine that enabled the fighter to make sharp dives to avoid the attacking Spitfires and Hurricanes, which used traditional carburetors. The British, however, quickly learned to perform a fast flick of the aircraft before diving, a procedure that would fill the carburetor and prevent the engine from cutting out in a dive. But the absence of fuel injection would cause concern even for RAF veterans throughout the battle when an engine would cut out during a dogfight because of a lack of fuel.

Willy Messerschmitt had designed the Bf-109 in the mid-1930s and it went through some modifications based on its combat use in the Spanish Civil War. A larger engine, giving the Bf-109 an added 400 horsepower, and the addition of 20mm cannons to each of its strengthened wings made for a fierce attack weapon. The plane was not without its faults and its narrow stance often caused mishaps on landing and takeoff.

Reginald J. Mitchell, the father of the Spitfire, also began design work on his all-metal fighter in the 1930s. Like the Bf-109 and the Hurricane, the Spitfire progressed from a fixed-pitch wooden propeller to a three-blade, variable-pitch, metal propeller that progressively increased its speed. Mitchell, a born engineer, amazingly got his start at age 16 working as an apprentice in a company that produced steam locomotives. He knew metal and was able to produce a sleek, elliptical-winged craft packing eight .303 Browning machine guns and powered by a 1,000-horsepower Rolls Royce Merlin engine.

The Spitfire, and other metal monoplanes like it, necessitated the retraining of workers to make them familiar and comfortable with working with light metal alloys rather than the traditional fabric-over-frame airplane construction.

Sydney Camm of Hawker Aircraft began working on the Hurricane in the early 1930s. It also was eventually powered by the Merlin engine. He developed a thick, sturdy wing and a wider, more stable undercarriage than either the Spitfire or the Bf-109. Much of the Hurricane was covered with fabric rather than metal, making it easier to build and easier for ground crews to repair. Experience also would show that the Bf-109’s cannon fire would pass cleanly through the craft, often without causing the extensive damage suffered by all-metal monoplanes.

The British produced more Hurricanes than Spitfires, and that is the reason the Hurricane is credited with more kills in the Battle of Britain. Part of that success is attributed to the fact that the Hurricanes were more often deliberately sent against the slower moving Luftwaffe bombers while the faster Spitfires tangled with the cannon-equipped Bf-109s. The Hurricane also had another key advantage over the other two fighters: its wheels retracted inward and its wide stable landing gear made the craft easier to land and take off from rugged grass strips.

All three aircraft were superb planes for the day, and in the end it often came down to the skill of the individual pilot and a bit of luck that determined which adversary would be shot from the sky. In addition, the Germans initially had a solid system of pulling their downed airmen from the English Channel via pontoon planes and fast boats, but the British eventually put an end to that.

The RAF pilots had a major advantage in that they were often fighting directly over friendly territory, which gave them more time in the air, while the German fighters had a more limited time over the target before fuel concerns prompted them to head homeward. The Germans explored, but never developed, drop tanks to increase their time over their targets.

The close-in fighting also meant that a rather substantial number of crashed British and German airplanes were scattered across the British Isles. A remarkable and often overlooked group, the Civilian Repair Organization, proved to be highly efficient in salvaging nearly every scrap of airframe possible. The metal was melted down and much of the German metal took to the air yet again in the form of new Allied aircraft.

The Civilian Repair Organization had an amazing record of getting RAF aircraft back in the sky. Fully 61 percent of aircraft crossed off squadron lists because they could not be repaired locally were successfully brought back into the fight by the organization. Even before the war began, the RAF had recognized the rather urgent need for a vehicle that could transport fighter planes by road with the removed wings stowed alongside. A low-riding trailer was developed and tested within days. The trailer system later proved invaluable in transporting damaged planes to central repair and smelting facilities.

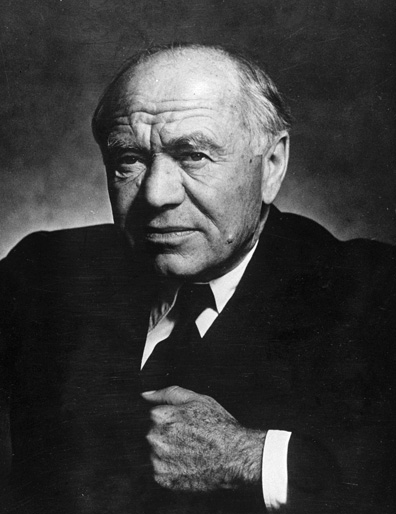

In May 1940, the Civilian Repair Organization fell under Minister of Air Production William Maxwell Aitken, First Baron Beaverbrook. Beaverbrook took forceful command of the ministry. From that point on, it was Beaverbrook and not the Air Ministry that decided what types of aircraft were produced and in what quantities. Fortunately, Beaverbrook took a quick liking to the taciturn Air Chief Marshal Hugh S. Dowding. Beaverbrook and Dowding formed a solid bond against Dowding’s critics in the Air Ministry.

Beaverbrook was a bold man of action. He was not above sending his Civilian Repair Organization staff to raid RAF squadrons for spare parts and engines that he then had delivered to production lines. He also relied on business experts outside the aircraft industry to help improve aircraft production.

Beaverbrook’s aggressive approach was evident early on when he ordered Supermarine, the company that had created the Spitfire, to take over a second Spitfire factory run by another firm that was lagging dramatically in production. He bluntly directed that Supermarine take over the factory in Birmingham and to forget plans to produce Wellington and Halifax bombers there as well. Soon Spitfire IIs, a slightly improved model with a higher-boost Merlin XII engine, were rolling from the factory, which was located farther from the danger zone.

Beaverbrook advocated the ferrying of completed aircraft from the United States to England despite the Air Ministry’s belief that it would prove impractical. He prevailed and was proven correct. The Civilian Repair Organization staff developed a system whereby fighter pilots flew damaged aircraft directly to centers where they were promptly repaired and the plane and pilot quickly put back into action.

Dowding, who was Reichmarschall Hermann Göring’s opponent during the campaign, advocated that the British use American-produced, 100-octane aviation fuel while the Germans relied on its standby, a lower grade 87-octane fuel. The specialized fuel helped offset the advantages of the German fuel-injected engines, but Dowding’s decision was a risky one because the fuel needed to be imported from the United States, which at the time was a neutral nation, using limited financial resources and shipped through heavily infested U-boat waters by vulnerable merchant ships. Dowding made several other crucial decisions early on that shaped the outcome of the battle, including the use of armor-plated cockpits similar to those the Germans used to protect their pilots.

Dowding, a diligent administrator and an impatient technician, was feared by the Air Ministry. He had a few glaring faults; for example, he could be unnecessarily caustic at times, and he often readily deferred to his specialists rather than investigating matters for himself. The specialists told him that self-sealing fuel tanks would be too heavy for fighters, something that was later proved to be incorrect. He was relatively naive when it came to boardroom politics, which hampered his career at the end, but oftentimes his demands, such as the need for bullet-proof glass on his fighter planes, proved to be right on the mark.

Although the Germans were among the first advocates of what was to become known as radar, it was the British who made determined and successful strides forward with its development in the 1930s. They also developed the Identification Friend or Foe system of placing a device onboard to identify friendly planes to radar crews on the ground, and it was Dowding who gave the first go-ahead for radar.

Ultra was another key component to the British defense system. Information from the intelligence program was collated for Dowding at Bentley Priory. By breaking the German codes, the British came to better understand the Luftwaffe’s objectives. The decoding operations and the comparatively sophisticated integrated radar system were heavily cloaked in secrecy.

Perhaps one of Dowding’s greatest contributions came before the Battle of Britain. Rather than going with the flow, Dowding protested loudly during the war in France when his superiors assigned four of his fighter squadrons to France and allocated six more squadrons if needed. Dowding argued that he needed fully 52 fighter squadrons, later raised to 60, to defend the homeland. He vehemently argued that Hurricanes should not be sent to France. He believed that sending British fighter aircraft to the rapidly deteriorating situation in France with poor airfields and without maintenance facilities and proper radar would prove disastrous. In Dowding’s view, France was a lost cause and Britain could survive only if she had enough fighters to protect her air space, crucial ports, and her infrastructure from the powerful Nazi air armada.

Near-term events proved Dowding’s assessment correct. Between May 10, 1940, and the so-called Miracle of Dunkirk between May 26 and June 3, the Germans destroyed the French Air Force and largely incapacitated the assorted collection of British bombers and the 10 fighter squadrons that had been sent by then to France’s aid.

On May 15 Dowding asked to meet with Churchill and his war cabinet. During the meeting, Dowding warned them against sending any more fighter planes to France. At that time, Dowding only had 46 squadrons. He reiterated his need for an absolute minimum of 52 fighter squadrons for the defense of Britain. Churchill recalled the meeting a bit differently. A few days later the prime minister ordered another 10 fighter squadrons to France.

That was too much for Dowding, who sprang into action and wrote a blistering letter to his superiors. Cutting his home defense squadrons to 36 in a desperate and futile attempt to save France, he warned, would severely weaken Britain and “involve the final, complete and irremediable defeat of this country.” The letter garnered the support of his immediate superior, although Hurricanes continued to be drained in limited numbers from Dowding’s command for political expediency until the fall of France.

Dowding’s letter and his calculations on the number of squadrons needed proved to be on the mark, but his bold action in putting his concerns in writing generated quiet animosity among Churchill and others. The letter and later political infighting would eventually lead to Dowding being eased from his position as head of Fighter Command once the Battle of Britain had ended.

While Fighter Command acquitted itself quite well against the German air armada, it was the Royal Navy that perhaps deserves more credit for being the unheralded hero in the Battle of Britain and in earlier skirmishes with the Germans. Hitler’s forces did manage to take both Denmark and Norway just months earlier in the world’s first combined land, sea, and air campaign, but the taking of Norway came at a substantial cost to the German Kriegsmarine. The Kriegsmarine lost one heavy cruiser, two light cruisers, 10 destroyers, and six submarines. In addition, two battleships and another heavy cruiser were badly damaged in the Norwegian campaign.

On July 16, Hitler ordered the Kriegsmarine to begin making preparations for an invasion of Britain, codenamed Operation Sea Lion, tentatively scheduled for mid-August. Some historians contend, perhaps rightly, that the Kriegsmarine was so weakened by its naval losses during the Norwegian campaign that it could not have properly supported a full-scale landing campaign against Britain as envisioned in Sea Lion. Although Churchill and others had eyes focused on the air campaign, a successful German landing could not have been prevented without sufficient naval protection from the powerful British Royal Navy.

The Kriegsmarine was well aware of its shortcomings, and its leaders were not above tossing obstacles, both real and imagined, in the way of the invasion planners. The Royal Navy was a powerful and formidable opponent, especially in defense of its homeland, and it would be difficult to protect any landing force against it. The Germans faced a host of challenges to a cross-Channel invasion. Chief among those was that they lacked a reliable landing craft that could navigate the choppy and unpredictable English Channel while withstanding British air, artillery, and sea attacks.

Although Göring, a World War I ace fighter pilot, was in overall command of the Luftwaffe, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring as commander of Luftflotte 2 handled much of the day-to-day activity during the campaign. Kesselring, who was affectionately called “Uncle Albert” by his men, worked closely in planning the daily attacks with Luftflotte 3 commander Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle. At the outset of the campaign, Luftflotte 2 and Luftflotte 3 had a combined total of 1,841 aircraft. The total number included 769 twin-engined bombers, 248 dive bombers, 168 Bf-110s, and 656 Bf-109s.

Together, the two carefully analyzed each raid and adjusted air tactics accordingly. The Luftflotte commanders often resorted to feints and circuitous routes in an effort to mislead the British as to the true targets for German bombers. One of their more interesting refinements was the development of a special beam, codenamed Kickebein, which led German bombers to targets. Once it became operational, the British worked to nullify it with jamming countermeasures.

Tactics varied considerably during the campaign. The first phase from July 10 to August 12 focused on attacks on British coastal convoys and air battles over the Channel. The Germans were determined to sweep the Channel clear of potential opposition to a landing and to create the type of stunned paralysis that the Luftwaffe had produced earlier in both Poland and France. The Germans believed they could pull Fighter Command into what the Luftwaffe believed would be a favorable attritional air battle that would weaken the British well before Operation Sea Lion began. Hitler’s forces felt they could not lose; if the British planes did not rise to the occasion, they would sink the British convoys, causing the belt to tighten even further on the island.

Dowding recognized the dilemma and cautioned his superiors that he could only provide minimal protection in the Channel without severely hampering his force’s ability to directly protect the homeland. Pressure mounted on him as more ships were sunk, and eventually he repositioned some of his fighters closer to the Channel where they could provide some added convoy protection even if those locations exposed the planes and airfields to more attacks from German marauders. Occasionally the German fighters did spring free from defending their bombers and did make attacks over Kent and elsewhere. And bombers occasionally came in from the North Sea during this period to drop a few reminders of their presence.

The repositioning of his fighters and the incursions concerned both Dowding and his superiors. Even more troublesome to him was the fact that British fighters downed in the Channel at that point had no dinghies, no sea dye, and no organized way to be retrieved. He took steps to ensure that those shortcomings were resolved.

The British also saw the advantage of the German Schwarm, in which the leader was positioned slightly ahead of the others and with the far outside pilot flying slightly behind the others to guard the tail of the formation. And all flew at slightly different levels to prevent collisions. Fighter Command attempted to copy that formation, but it would take time to master the rather complex system that the Germans had polished in years of combat going back to the Spanish Civil War.

The Germans resorted to some clever deceptive practices during this time frame. On July 18, for example, British radar detected a fleet of aircraft circling for height near the Strait of Dover in preparation for what appeared to be a bombing raid. It turned out to be a flight of Bf-109s circling to lure in the British fighters. They nailed a Spitfire without a loss of their own. Kesselring found that he could force the British defense to divide by attacking two coastal convoys at the same time. Attacks off Dover and near the Thames Estuary on July 24 had the desired result and proved an effective tactic from then onward.

About the same time, the British began allowing fighter pilots to have their gun sights ranged in to their individual liking. This enabled the more brazen to score more direct hits with head-on attacks against German planes. Fighter Command also began allowing pilots to use a greater mixture of the new De Wilde incendiary bullets that provided a bright yellow flash on impact. The incendiary bullets had a severe damaging effect while serving as a superb aiming device for the British pilots. The British fighters also relearned the importance of striking from out of the sun to take the enemy by surprise.

Kesselring had other tricks up his sleeve, including a July 25 low-flying run of Bf-109s coming in at near wavetop height near Dover to lure the British fighters to them so the Stukas could be free to dive bomb a convoy. The British convoy called for help, and when a flight of nine Spitfires came to the rescue they were surprised by a large and well-prepared force of Bf-109s that ravaged the Spitfires and sent a flight commander to his death without the loss of a single German fighter.

That and subsequent losses for the next few days convinced the British that future convoys should only attempt to pass through the Strait of Dover at nighttime. Dowding resisted efforts to force him to provide more protection for the convoys, mostly carrying coal to industrial areas. From that point on, the British relied heavily on the existing railway system for transporting coal and related domestic materials.

This change saved countless Fighter Command airmen as well as British seaman who otherwise would have been lost. Just before that, during a three-week period in July, some 220 flyers had been lost in the Channel, along with a substantial number of seamen.

The modest change in British tactics had another significant effect. The Germans continued to overestimate the numbers of fighters downed and with fewer enemy airborne they came to believe the British were on their last legs, or nearly so. The Luftwaffe had failed to factor in the British system of limited response to aerial incursions and failed to calculate Beaverbrook’s ability to produce new fighters. All these factors contributed to the Luftwaffe’s belief that it, and not the British, was winning the day. But the German system of distinct and separate air fleets resulted in overlapping and duplicated systems that often enabled convoys to slip through the Channel relatively unmolested.

Perhaps frustrated with the progress of the campaign, on August 1 Hitler issued orders on to Göring to destroy the RAF as quickly as possible. Together with his Luftflotte commanders, Göring drew up plans for Adlerangriff (Attack of the Eagles) to achieve the goal. The attack would begin in earnest on Adler Tag (Eagle Day), designated August 13. The goal was nothing less than to wipe out Britain’s Fighter Command. “Within a short period you will wipe the British air force from the sky,” Göring told his pilots.

This set the stage for the second phase of the Battle of Britain, which ran from August 13 to August 23. Leading up to Adler Tag, Göring planned preparatory attacks on British radar stations. The attacks were directed against four radar sites, with their tall masts serving to attract the Bf-110 fighter bombers. Three of the sites were incapacitated, with only a station in Kent remaining operational. The Germans were quick to exploit the 100-mile-wide gap that had been created in the defense system.

More than 1,400 Luftwaffe bombers and fighters were involved in attacks against RAF assets in the Thames Estuary on Adler Tag, with only 13 British planes downed and more than three times that number lost by the attackers. Dowding’s previous decision to feed the planes slowly and piecemeal into earlier air battles proved correct. The British now had the resources necessary to fend off Germany’s determined effort to break Britain’s will to resist.

On August 15, Göring ordered Luftflotte 5, which was based in Norway, to augment the attack by Luftflottes 2 and 3. That day the Luftwaffe flew 2,000 sorties, but Luftflotte 5, which lacked Bf-109s, suffered heavy aircraft losses because its slow-moving, poorly armed Bf-110s were no match for the British single-seat fighters. Three days later, in another major air battle, the Germans lost 60 aircraft, half of which were bombers. Frustrated at the loss of so many bombers, Göring issued orders that future Luftwaffe air assaults were to consist of a two-to-one ratio of fighter escorts to bombers.

By the end of the third week of August, the British were still standing and resisting the onslaught. The third and final phase of the Battle of Britain, which began on August 24, marked heavy German assaults on British airfields. Working under a directive from Göring, the Germans bombed airfields around the clock all over the United Kingdom, even if it meant only one aircraft striking an airfield, to keep the British on edge. British radar operators were frazzled with aircraft forming up and those coming in as large numbers of German fighters and bombers took to the air. The tight German formations often managed to fight their way through to their targets, creating second guessing and rumblings by those who served under Dowding. Many had advocated large-scale fighter attacks against the intruders rather than Dowding’s piecemeal method of sending the fighters into the fray.

While this argument smoldered, another incident occurred that was to mark changes in the way the battle was fought. During an August 25 early morning raid, one He-111 crew overshot its target and bombed London in the darkness. This was the beginning of total war, with the British deciding to bomb Berlin in reprisal, leading to further deaths. The Nazi leaders were understandably embarrassed because they had promised that Berlin would never be bombed and so further escalation began.

As the British garnered success in downing enemy aircraft during the day, the Germans developed an improved guidance system that made their nighttime bombing efforts more successful. And that system proved effective when used on cloudy daylight raids as well.

The British continued their assaults on German bombers, avoiding the fighters whenever possible. That way they could inflict the heaviest damage possible while incurring fewer losses. But the Germans continued their efforts to overwhelm the defenders with sheer numbers coupled with deceptive tactics. A Luftwaffe assault on August 30 proved critical, with a convoy attack near the Thames Estuary drawing off the defenders, when 40 He-111 and 30 Do-17 bombers, escorted by nearly 100 fighter planes, crossed over England’s south coast to hit a series of airfields.

A second wave of bombers inflicted even further damage on the airfields and knocked out the radar system for England’s entire southeast coast. A third wave headed toward the Thames Estuary before swinging southward toward Biggin Hill, where it caused severe damage to RAF hangars, workshops, stores, and quarters.

By the end of that bloody day, 36 German aircraft had been shot from the sky, with a loss of 25 British fighter planes and 10 RAF pilots. The Germans, for their part, could take consolation in the devastation caused to sector airfields with their resourceful and seemingly relentless attacks. The British hardly had time to land and refuel between attacks, and if the Luftwaffe could manage to catch the fighters on the ground, future attacks could prove decisive.

The Germans came on strong the following day, putting 1,300 fighter sorties into the air to protect some 150 bombers in their runs on the airfields with the same energetic thrusts used the previous day. A number of the Brit pilots were caught on the ground, with devastating results. That day 39 RAF fighter planes had been lost, with 13 pilots killed, while the Germans lost 39 aircraft. The British were near exhaustion as the result of the determined and improved German tactics.

During this phase, Britain’s Fighter Command lost 200 more fighters than they received and of the 1,000 RAF pilots, 231 had been killed, wounded, or missing during this two-week period. In addition, six of seven sector fields had been badly damaged along with five forward airfields.

The Germans pressed their attacks on the airfields over the next several days, focusing in on the sector airfields in southern England rather than Tangmere and Kenley, the only two surviving airfields in that area. Luftwaffe commanders also added aircraft factories to the objectives, further lessening damage to the two fields and giving the British more time to repair and bring the other airfields back into the fight. The Germans believed their own inflated intelligence reports, especially Kesselring, who contended that the British had few fighters left, even though Fighter Command had flown 1,000 sorties for the first time on August 30.

In reality, things had grown desperate for the RAF. Dowding had lost a quarter of his fighter pilots in the last two weeks of August, and another quarter of his pilots were fresh-faced volunteers with no real combat experience. But Dowding had calculated well; if he could protect British skies through September, his wily opponent would be forced to postpone the invasion with the coming of inclement weather.

The Germans simply would not rest. In September and October, the Luftwaffe focused on shattering the British will to resist with sustained air attacks on London, first by day and then by night. The London attacks were in direct response to continued RAF attacks on Berlin. This redirection away from the airfields provided a breather and allowed Fighter Command to further rebuild its airfields, infrastructure, and supply of pilots.

On September 7, the Germans mounted a bombing effort that included nearly 1,000 aircraft. An impromptu British large-scale effort, known as Big Wing, in which Fighter Command threw all of its strength against the Luftwaffe attack without holding back a reserve, did not have the desired result on the intruders. That led to still further behind-the-scenes infighting between Dowding and his opponents. The Germans had also given their new 3,600-pound high explosive bomb a try during that attack, leading the Joint Intelligence Committee to believe that a German invasion was imminent, causing further alarm among the defenders.

At the conclusion of the September 7 attack, Göring boasted of the RAF, “They have had enough.” But he was wrong. The RAF continued to contest the relentless German air attacks even with dwindling numbers of fighter aircraft.

The damaging London raids shifted to nighttime two evenings later, and by September 13 there were only 80 Hurricanes and 47 Spitfires available. The fighting on September 15 provided quite a spectacle as nearly 200 Spitfires and Hurricanes tangled with the enemy over London. And twice that day some 300 British fighters were in the air defending southern England. For their part, the Germans had put 400 fighters of their own aloft to protect approximately 100 bombers. But it was the large-scale formation over London that day that convinced the Luftwaffe that Fighter Command was still alive, functional, and steadfastly determined to defend Britain.

The RAF claimed 185 victories that day, but new research in German archives has shown it to be well less than a third of that. The actual numbers did not diminish the propaganda influence of the British efforts. “Using only a small portion of its total effort, the RAF today cut to rags and tatters separate waves of murderous assault upon the civilian population,” said Churchill.

Fighter Command still had not taken full control of the air, and the Germans continued to make daytime and nighttime raids against the embattled country. But the weather was changing and just by remaining as a cohesive defensive force, Fighter Command had won the long, strung-out Battle of Britain. The Luftwaffe did not win firm command of the air over Britain and its beaches, and by the end of September British intelligence had learned that Sea Lion was postponed until further notice.

The Luftwaffe then resorted to nighttime bombing of the island, and Hitler turned his long-term attention toward the rolling steppes of the Soviet Union. It was the lure of Lebensraum that was to siphon off German military and its material strength over the next several years. That, in turn, gave Britain and the Western Allies time to regroup and rebuild for their eventual reentry onto the Continent in the final phase of what was to become an unwinnable two-front war for Hitler’s forces.

The spitfire never had 8 .50 caliber machineguns!

8 .303 or 7.7mm in the A Wing Mk V model

Would have been nice to mention the effect Polish, Danish and Finnish pilots had on the Battle of Britain. Originally discounted by the British they made a tremendous difference in the outcome.