By Gene E. Salecker

The first explosion came as a complete surprise to everyone around Pearl Harbor. The Sunday had started out clear and bright, but the sky quickly darkened as great clouds of thick black smoke rose high above the burning ships.

Fuel oil spilled atop the water and caught fire, sending giant licks of flame spreading out across the surface. In an instant, over two dozen ships were in danger. Only the quick actions of their captains and crews could save them. It was not December 7, 1941, but May 21, 1944, and it was not the Japanese that set off the first explosion. It was careless smoking.

The whole ordeal began on May 15, when dozens of landing ship, tanks (LSTs), scheduled to take part in the upcoming invasion of the Japanese island of Saipan in the Marianas, headed toward the Hawaiian island of Maui for a rehearsal. Saipan and the neighboring island of Tinian would be invaded by the Northern Troops and Landing Force of Task Force 56, consisting of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, the XXIV Army Corps Artillery, and the Saipan and Tinian Garrison Forces, a total of 71,000 men. A Southern Troops and Landing Force, made up of the 3rd Marine Division, the 77th Infantry Division, and the III Army Corps Artillery, some 56,500 men, was assembled to capture Guam.

To carry the troops to Saipan, the Navy had assembled 110 transport vessels, including 10 high-speed destroyer transports (APDs) and 47 LSTs, the big transport vessels that could beach themselves on an invasion beach, open their bow doors, drop their ramps, and belch forth invading troops. To help get the men ashore over a fringing reef, the Navy had 579 troop carrying landing vehicles, tracked (LVTs or amtracs), and 140 armored amphibian tanks. The Army’s 105mm howitzers would be carried ashore in DUKWs, the amphibious version of the 2.5-ton truck. Both the LVTs and the DUKWs would be carried to the Marianas in the bellies of the big LSTs.

Both inside and outside, the LSTs were loaded with ammunition, equipment, vehicles, and men. “Much of the cargo was placed by the Army quartermasters on the tank deck [i.e., enclosed lowest deck], piled about three feet deep,” recalled Ensign Carl V. Smith of LST 224. “They then covered all their cargo with 1 x 6-inch rough lumber called dunnage. It was crisscrossed so that the [LVTs] could be parked on [top of] it securely.” Once the lumber was in place, the LVTs or DUKWs were backed into the mouth of the LSTs and parked atop the wooden supports. Each LST could carry 17 LVTs or LVT(A)s (amphibious tanks) or 11 DUKWs.

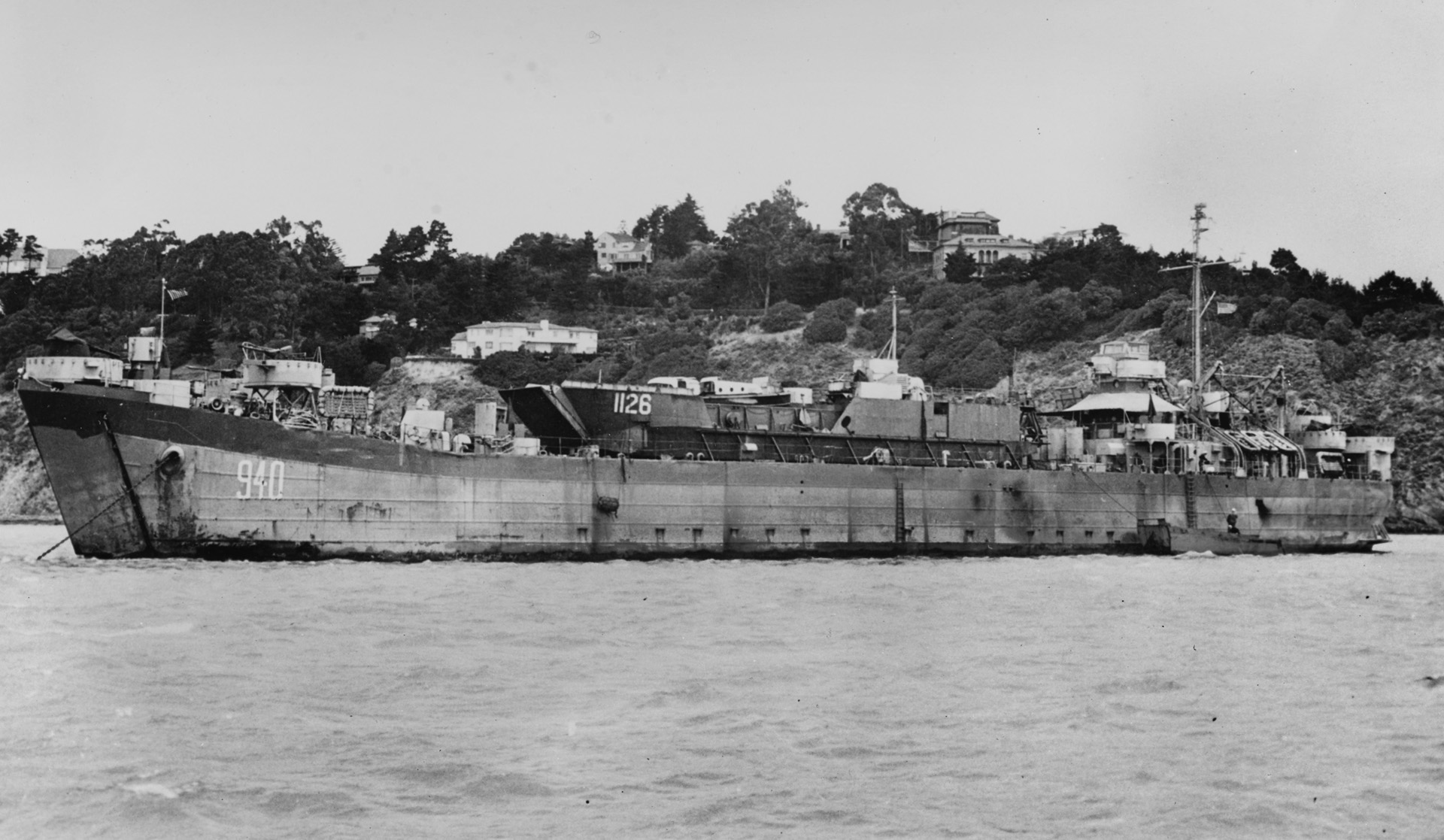

Many of the 328-foot-long LSTs were piggybacking a smaller, 120-foot long landing craft, tank (LCT) on their wide open, flat main decks. The smaller ship was hoisted onto the larger craft by cranes at Pearl Harbor and placed atop sturdy wooden greased skids spread perpendicular across the main deck. Once chained in place, there was a small space underneath the LCT that provided a shaded area for many of the Marine Corps or Army passengers to pitch their cots if they did not want to sleep in the enclosed tank deck, which stank of gas fumes. Other Marines and soldiers simply elected to sleep inside the open-topped LCT itself. Once the big LST arrived at the invasion beach, the ship was ballasted to lean to one side, the chains were unhooked, and the LCT simply slid off into the ocean. The crew then climbed in and went about the business they were trained for.

If an LST was not carrying an LCT, it was probably carrying two large floating pontoons attached to either side of the hull. Since many invasion beaches were too shallow even for the flat-bottomed LSTs to get close enough, floating pontoons had been designed to fill in the gap between the dry sand and the end of the LST ramp. Ensign Smith wrote, “Pontoons were made of steel cubes measuring 6’ x 6’ x 6’. The steel was about 1/8 inch thick. These cubes were joined together by six-foot steel angle irons, and the pontoon could be as long as the need dictated…. Cables lashed it into place [on the sides of the LST]. When it came time to launch, the cables were released and the pontoons fell into the water.”

The entire invasion fleet was commanded by Admiral Raymond Spruance, with the Amphibious Force commanded by Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner. Knowing that many of his ship commanders and crews were young and inexperienced, especially on the LSTs, Turner scheduled five days of full-blown rehearsals around Hawaii for mid-May, “The biggest and longest held to date in the Pacific campaigns.”

Unfortunately, things went wrong from the start. On the night of May 14, while the LSTs and other ships were moving toward the rehearsal beach on Maui, the weather turned downright nasty. Strong winds and rolling waves battered the various craft as they moved through the darkened waters. At 2:19 am on May 15, the chains holding down LCT 988 on top of LST 485 snapped.

“The weather was rough and the strain on the cables was too great,” reported Marine Corps historian Carl Hoffman. “The craft was pitched overboard with the sleeping men aboard. Nineteen men were either missing or killed, and five were injured as the craft was rammed and sunk by the next LST in column.”

About 25 minutes later, as the seas continued to batter the rehearsal fleet, another landing craft, LCT 988, pitched off the deck of the Coast Guard-manned LST 71. Although the bow ramp was up when LCT 988 hit the water, it quickly became waterlogged and a number of Marines that had bedded down inside the open vessel were swept away or drowned. Although swamped, the landing craft stayed afloat and was eventually towed back to Pearl Harbor.

Unfortunately, before the night was through, one more of the smaller vessels, LCT 984, was prematurely launched off the deck of LST 390. Unprepared for the disaster, the LCT had its engine room doors open and, upon hitting the water, its front ramp came down. The open ramp and doors caused the craft to become “so waterlogged that it capsized.” Bobbing up and down in the middle of the rehearsal lanes, LCT 984 became a “marine hazard” and was later sent to the bottom by some well-placed gunfire from a submarine chaser. There were no survivors out of those who had been swept overboard.

Perhaps the reason why LCT 988 and LCT 984 broke their chains in the heavy seas was because they had been equipped as mortar gunboats. To add a little punch to the landings, Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill, in charge of the ships and amtracs transporting the men toward the shore, had turned three LCTs into floating gunships, equipping each with eight 4.2-inch mortars. The mortars were welded to the decks, and each craft was loaded with 1,250 cases of mortar shells, with two shells to a case. Perhaps in the heavy seas the additional weight of the mortars and shells had put too much strain on the chains holding the LCTs in place. Three LCTs were gone, dozens of lives were lost, and the rehearsals had not yet begun.

Throughout May 15-19, trouble haunted the rehearsal. Several LSTs collided with each other, causing minor damage, while many more had broken ramp chains once their wide bow doors were opened and their ramps were lowered. Additionally, two DUKWs sank as the heavy waves continued to pound the ongoing rehearsal. Fortunately, all crews and passengers were rescued.

In spite of the tragic loss of three LCTs and their crews and many Marine passengers along with the minor accidents, the rehearsals went on. After the fifth day, Admiral Hill and others made an assessment. Hill deemed the activity “very ragged and poorly conducted.” Unfortunately, the weather had played a big part. Other officers, however, felt that the rehearsals “proved to be immensely beneficial in providing much needed supervised drill for [the] Commanding Officers of the LSTs in the expeditious launch of tractors [amtracs] at the right time and right place.”

The rehearsals were over by 1 pm on Friday, May 19, and most of the LSTs headed back to Pearl Harbor. The only ships left behind were those whose crews were trying to repair broken ramp chains or close stubborn bow doors. While the main group of ships was returning to Oahu, many of the amtrac and DUKW crews took the opportunity to refuel their vehicles. In most cases, up to one hundred 55-gallon drums of high-octane aviation gasoline had been strapped to the forecastle of the LSTs’ top decks. Of course, the refilling of the LVTs or DUKWs left dozens of empty or half-empty drums of aviation gasoline tied on the bow of each ship, a dangerous situation since the remaining fumes were highly combustible.

Equally as dangerous was the fact that many of the Marines and Army personnel were using the gasoline to weatherproof their rifles. Rather than bunk inside the LST, where the air smelled of exhaust fumes and gasoline, many Marines and soldiers set up their cots on the wide open main deck, bunking under the LCT or around and inside the many jeeps, trucks, or ammunition-laden trailers crowding the main deck. With their rifles exposed to the corrosive sea air, many of the men began wiping a layer of gasoline on their weapons. It was not unusual for at least one 55-gallon drum to be equipped with a spigot so that the Marines and soldiers could siphon off a bit of gasoline to coat their rifles. This also left a half-empty drum of gasoline.

Most of the returning LSTs maneuvered through the entrance of Pearl Harbor on Saturday morning, May 20, and then turned left into a narrow channel that led to a shallow area of Pearl known as West Loch. Too shallow for most of the deep-bottomed combat ships, West Loch was an excellent anchorage for the flat-bottomed LSTs, which drew only 14.5 feet of water. During the infamous December 7, 1941, attack, the Japanese had concentrated on the ships and facilities in East Loch, missing the large Naval Ammunition Depot on Powder Point in West Loch, which housed most of the powder and ammunition for the Pacific Fleet. In 1941, the depot had been housed on only 200 acres of land. By May 1944, it had expanded to cover 537 acres and contained almost every kind of munition, including torpedoes, fuses, detonators, mines, and shells.

Situated along the sides of West Loch were sets of mooring posts known as tares, consisting of a few dolphins or pilings resembling long telephone poles, wrapped with iron bands and sunk upright into the bottom of the harbor about 25 feet from shore. When a ship docked at a tare, it simply moved up alongside the dolphins and tied up sideways, bow and stern. Other crews that needed to dock simply pulled their vessel up alongside the first ship, threw a few facile rope bumpers between the two craft, and fastened the two ships together with thick hawsers. In this fashion, several ships could dock alongside each other at each tare. Loading and unloading of the vessels was done by small boats or landing craft, usually through the big bow doors and ramps.

There were a total of 10 tares or mooring stations at West Loch. Tares 1 through 4 were situated along the West Loch channel below Powder Point and the Naval Ammunition Depot. Tares 5 and 6 were north of and opposite Power Point. Around a little outcropping of land known as Intrepid Point sat Tare 7, while straight west across a wide shallow bay known as Walker Bay were Tares 8, 9, and 10. West, beyond the depot, was a shallower back bay that was usually used by even smaller, shallower draft vessels.

Through Saturday and into Sunday morning, several LSTs came and went from West Loch, tying up to the different tares or queuing up to Tare 3, the water dock, to top off their fresh water tanks. After docking, some of the LSTs disgorged their amtracs or DUKWs for simple maintenance or cleaning. These moved onto a parking area set up between the western tares and a wide sugar cane field bordering the western side of the loch. By 3 pm on Sunday, May 22, there were five LSTs tied to Tares 5 and 6, five at Tare 10, seven at Tare 9, and eight at Tare 8. Additionally, there were three APD high-speed transport destroyers at Tare 7 at Intrepid Point and a cargo ship, SS Joseph B. Francis, unloading 3,000 tons of ammunition at the depot. Not far away, also waiting to be unloaded, were two barges containing another 3,000 tons of explosives. Tied up as the LSTs were, and packed to the gills with ammunition and equipment for the invasion of the Marianas, the situation was ripe for disaster. Noted one LST commander, “If one LST caught fire due to the nature of the cargoes on board, probably all the ships would be lost in one [tare].”

In the early morning of May 22, while about half the crew of each ship disappeared on shore leave, a group of civilian workers, including a number of Hawaiian-born Japanese, went aboard several ships to tighten down or replace the chains holding the different LCTs to the top decks. On board LST 353, the seventh ship of the eight at Tare 8, two sailors broke out a welder’s torch and began cutting and welding some angle iron needed to carry extra life rafts for their Marine passengers. A little forward of where the two men were welding, a group of African American soldiers from the 29th Chemical Decontamination Company was hard at work removing the 1,250 cases of mortar shells from LCT 963. Earlier that morning, after reflecting upon the loss of the two heavily laden gunships during the Maui rehearsals, Admiral Turner had decided to scrap the idea of the mortar gunships and retrofit the one remaining vessel, LCT 963, to a regular LCT. However, before the mortars could be removed with a welder’s torch the cases of ammunition had to be removed.

To facilitate the unloading, a 2.5-ton truck had been brought out to LST 353 and raised up to the top deck via the large cargo elevator near the bow. Since the LCT was elevated on the greased timbers, even with its bow ramp down it was higher than the truck. Because of this, the ammunition handlers placed slides from the six-foot-high lowered ramp to the raised tailgate of the truck, which remained on the raised elevator. With most of the handlers working inside the LCT and only a couple inside the back of the truck, the soldiers lifted the mortar round crates from the deck of the LCT and pushed them down the slides to the waiting truck.

Although this worked well for a while, a few crates slid off the slides and cracked open, spilling the twin mortar rounds onto the steel deck. After some time, when it was evident that this process was taking too long, it was decided to forgo the slides and simply load the crates by hand, passing them from one handler to another. By 3 pm, after one truck had been loaded and brought back to shore, a second truck was beginning to fill up when the loaders paused to get an accurate count, having been ordered to load no more than 110 crates in the truck lest the weight cause the elevator to suddenly collapse. While a few men stood inside the truck and counted, others broke out cigarettes in spite of the fact that LST 353 had a “no smoking” order in effect.

Unfortunately, the no smoking rule was disobeyed in other areas as well. Forward on the left side of the bow, just in front of the 80 drums of high-octane aviation fuel that LST 353 was carrying, one crewman and one officer were also smoking. “I had … come up from below deck and was sitting on the port side of the bow … talking to [Ensign Dean Delbert] Urich,” recalled S2/c James Henry Kane. “I had been smoking a cigarette, and I believe other people were smoking on the forecastle.” In spite of the “no smoking” orders and the proximity of the aviation fuel, several people were smoking on the bow of LST 353.

Shortly after 3 pm on Sunday, May 21, 1944, while hundreds of men were working or relaxing aboard the almost three dozen LSTs spread around West Loch, the bow of LST 353 exploded. In a split second, the peaceful Sunday afternoon was shattered.

Nobody expected an explosion, so nobody was sure exactly when or how it happened. An official military investigation fixed the time as 1508 hours, but it is obvious that the investigators were not sure either and took that time as an average. Likewise, the investigators were not sure what caused the explosion. Some suspected sabotage by the civilian work crews, while some felt a miniature Japanese submarine had slipped into the harbor. The investigative board fixed the cause as a “dropped mortar shell,” but many others felt it was caused by careless smoking.

“I’ve seen a lot of mortar shells dropped,” reported PhM William Johnson from LST 69, “and unless they’re armed, they don’t go off. They have to be armed ahead of time.” Carleton Drake, a Marine radioman assigned to LST 353, agreed. “Well, those 4-inch shells aren’t detonated until they’re ready to fire.” None of the shells aboard LCT 963 were armed ahead of time, and in fact some had been dropped earlier in the day, and none had exploded.

The most likely cause of the explosion was careless smoking. The Navy court of inquiry had numerous eyewitnesses who claimed that the blast came from among the gasoline drums on the bow, including Ensign Urich and Seaman Kane, who were both blown overboard by the explosion. “My first thought,” Kane said, “was the gasoline had gone up…. There was a deep, long, drawn-out boom.” Carpenter’s Mate 2/c Henry Bonne, with the 1035th Construction Battalion, was working nearby when the explosion went off. Because of his work in construction, Bonne knew the difference between a gasoline and an ammunition explosion. “I have seen lots of gasoline fires and dynamite explosions, and I am sure it wasn’t ammunition,” he recalled. “There was a dense black smoke with reddish-orange flame and it looked to me like a couple of barrels of gasoline.” Unfortunately, anyone close enough to know for sure was gone and the whole loch was suddenly in danger.

The explosion on the bow of such a heavily combat-loaded ship scattered flaming debris and shrapnel in all directions, landing on ships moored at Tares 7 through 10 and some of the vessels moored in Walker Bay. The blast had enough force to send objects and people flying into the air and shake ships at least 500 feet away. Windows at the Naval Ammunition Depot shattered. Immediately, the remaining stored aviation fuel drums on the bow of LST 353 began to burn and explode.

The ships on either side of LST 353 were in grave danger with flaming debris landing atop the stored gasoline drums on the bows of LSTs 179 and 39 moored port and starboard, respectively. Ships a little farther away also caught fire. The canvas tops of jeeps and trucks and the tarps covering ammunition-loaded trailers quickly caught fire. Most of the ships alongside and behind LST 353 began to burn. Throughout the loch, ships began to sound general quarters and crews began to man fire stations.

Seaman 2/c Chet Carbaugh was in his rack inside LST 39 reading letters from home when he felt the ship rock from the first explosion. “I ran topside,” he remembered. “It was a nightmare. There was smoke everywhere, shrapnel was falling down like rain, and the water was on fire from all the oil that had spilled.” Hoping to save his ship, Carbaugh joined other crewmen as they manned a fire hose and began to fight the fires quickly spreading across the entire vessel.

Shortly after the first explosion, a second, more violent explosion occurred. “This time the flames shot up maybe 75 or 100 feet into the air,” wrote Lieutenant William Zuehlke of LST 43, two ships to the left of 353. Although his crew rushed to break out the fire hoses, they were impeded by Marines and crewmen from the other ships rushing across LST 43 to get away from the burning ships to the right.

Dozens of Marines had set up cots with tents as awnings on the main deck of the Coast Guard-manned LST 69, which was piggybacking LCT 983. Marine Harry Pearce and his buddy, Sam, were on their cots underneath the LCT. “The blast just leveled everything. Sam and I were blown off our cots,” Pearce recalled. “All we had was our skivvies and our shoes. We each grabbed a helmet and put it on.” Looking around, they spotted Sergeant Paul Bass sprawled on the main deck, a victim of the concussive power of the explosions. “Blood was coming out of his eyes and ears and his nose and mouth,” Pearce said. The two Marines rushed to his side.

Crews on the other ships at Tare 8, to the left of LST 353, manned fire stations and started their engines, hoping to get away. Unfortunately, the engines on LST 69, three ships to the left, were down for repairs. Skipper Lieutenant (j.g.) Albert Gott rushed over to the vessel moored to his port, LST 179, to ask if 179 could tow him away when that ship left its mooring. Although the officer was willing, he said that Gott would have to sever the mooring lines to LST 43 on Gott’s right before 69 could be pulled free. Satisfied with the answer, Gott rushed back aboard his ship to see about severing the lines.

Regrettably, the exodus of hundreds of Marine passengers and crewmen from the burning, exploding vessels caused panic among the crews and passengers of the other vessels. As men poured over the railings from ship to ship, heading toward the innermost ship and shore, they created confusion among the other crews. Soon, there were few crewmen manning the fire hoses as the gasoline drums and ammunition on LST 353 and now the other ships continued to burn and explode.

The crews on the seven LSTs in Tare 9 were also fighting to put out the flaming debris that had landed on their decks. A crewman on LST 23, the fifth ship in the tare, recalled, “Debris from [353] covered other LSTs. Fire was breaking out on LSTs all around us. Our crew reacted quickly, and while some were throwing life jackets to men in the water, others were hosing down the decks to prevent fire from spreading to the 23.” While engine room personnel started their engines, many sailors on the ships in Tare 9 threw life jackets overboard or threw lifelines out from lowered bow ramps and pulled swimmers from the burning ships to safety.

“We started the engines, but because they had not had time to warm up, they kept dying when we tried to back down,” remembered Motor Machinist Mate 2/c Floyd Williams on LST 224. “I began to worry about all those fires on the main deck, all that ammunition stored in the tank deck, the gasoline on the main deck, and the fact that the engine room held us trapped below the water line.”

A 23-mile-per-hour wind coming from the northeast carried a large amount of flaming debris back toward the ships in Tares 9 and 10. As fires broke out on the tarps and canvas on the main decks, fire crews went to work. Soon, one by one, the ships in Tare 10, at least 1,000 yards behind the exploding ships in Tare 8, began leaving the mooring, some peeling off from the far side, others severing mooring lines with the ships on either side and backing straight out.

While some ships immediately headed for the narrow channel that led out of West Loch, others, looking at the congestion, turned in the opposite direction and headed into the safety of the shallow western back bay of the loch. Once there, they dropped anchor, continued to man their fire stations, and watched the enfolding disaster before them.

To the right and almost straight across from the exploding ships of Tare 8 sat the three high-speed World War I destroyer transport APDs at Tare 7. Being northeast of Tare 8, they were upwind of most of the flaming debris but were not immune from the heavy bits of jagged, hot metal that spewed outward from the exploding ships. While their crews manned fire stations, their small boats were sent out to help rescue survivors.

All around the loch people were coming to the rescue in spite of the growing conflagration that had now spread to the four ships on the end of Tare 8 and a burning slick of oil that was spreading over the surface of the water. Seaman 1/c Alex Bernal was alone in a small motor launch when the first explosion went off. “I was maybe 30, 40 yards away from the ship that exploded and [it] rocked the whole bay,” Bernal recalled. “You could see all kinds of debris going up sky high.” After rescuing one man, Bernal looked at the water around him. “We looked back, and fire started on the water and then the oil was burning. You couldn’t even see the sides of the ships.”

Perhaps five minutes after the first big explosion, a second massive explosion erupted from one of the ships on the end of Tare 8. The official court of inquiry reported, “A second large explosion occurred among one of these three LSTs [353, 39, and 179], which threw burning fragments in all directions and set fire to the high octane gasoline, bedding, canvas, and other flammable materials on the decks of the other LSTs.”

Marine Harry Pearce and his buddy Sam were carrying the injured Sergeant Bass by his arms and legs and passing from one ship to the next when the second explosion hit. “When the explosion went off, it picked me up and took me clear over the LST that Sam was on,” Pearce stated. “I came down on one of the guide wires that was holding an LCI on board. It just folded me in double, and I went round and round three or four times and fell on the steel deck on my back only to have Sam reach out and grab me and pull me underneath the LCI.”

While Pearce was blown clear across LST 274 and over LCT 982, Sam had been blown under the piggybacked craft. Unfortunately, when the concussive blast hit the two Marines they lost their grip on Sergeant Bass, dropping him between the two ships. “I can remember as I went up in the air,” Pearce said, “I saw him hit the water between the two vessels and just disappear. He was lost.”

Few crewmen remained aboard the fiercely burning ships when the order to abandon ship was finally given. The flames and continuing explosions had proved too much. Eventually, LST 39, the last ship moored at Tare 8, burned through her mooring lines, broke away from the other ships, and began drifting southward toward the few remaining ships in Tares 9 and 10. Although a few of the ships on the outer edge of Tare 9 had already peeled away to race for safety down the West Loch channel, several still remained. Faced with the danger from drifting LST 39, orders were given to chop the mooring lines between vessels and get out as soon as possible.

Executive Officer Anthony Tesori on LST 340 in the middle of seven ships recalled that the men “were able to sever hawsers holding [LST 340] to the other ships at the moorage and back away from the most dangerous area.” However, he admitted, “We did not escape entirely unscathed.” As the officer of the deck later noted, “[The second] and more intense explosion occurred in Berth 8, strewing our deck with wreckage and burning material. The firefighters of the vessel immediately flooded the entire main deck and the tank deck.”

As quick as they could, the ships at Tares 9 and 10 maneuvered to get away from the exploding vessels in front of them or the drifting, burning hulk of LST 39. Unfortunately, LST 480, sporting a pair of pontoons and sitting moored to the dolphins in the number one position at Tare 9, could not move until all the other ships outboard of her got underway. In trying to maneuver out of his tight spot, the skipper of 480 had moved the ship back and forth and had somehow gotten stuck on the other side of the dolphin pilings between the shore and the pilings.

By the time LST 480 got stuck between the dolphins, several other burning vessels from Tare 8 were drifting southward. A third large explosion forced any remaining personnel on any of the five outermost vessels to abandon ship. While the ships in positions six, seven and eight were engulfed in flames and exploding, the crews of the two middle vessels, LSTs 69 and 43, had fought back gallantly but fleeing personnel from the outboard ships had hampered firefighting efforts. When the third huge explosion came, throwing even more burning debris and shrapnel over the two ships, there were few firefighters left to battle the growing flames. Orders were given to abandon ship.

Eventually, two ships from Tare 8 managed to move away from the burning vessels and beach themselves on the shores of Walker Bay. They were the number two and three ships, LSTs 225 and 274, both sporting LCTs on their main decks. Although the skipper of LST 274 had agreed to pull LST 69 out of the nest if Lieutenant Gott’s crew could sever the mooring lines to the burning ships on his right, the men had been unable to cut the forward lines because of the raging inferno. Hoping to save his own ship, LST 274, Gott had been forced to move forward without taking LST 69. With his ship wrapped in flames, Gott fled to the fantail of 69 only to find that he was all alone. As LST 274 began pulling forward, Gott climbed over the port railing and jumped onto the fleeing ship. Behind him he left a floating, drifting, burning, exploding hulk.

The two outermost ships in Tare 8, LSTs 39 and 353, had drifted away from the others and begun to drift straight south. In the middle, LSTs 69, 43, and 179 remained together, perhaps stuck by cables, and began to drift toward Tare 9. Eventually, LST 69, piggybacking LCT 983, broke from the others and bore down on LST 480, still stuck between the dolphin pilings at tare nine. “A derelict burning ship drifted into us on our starboard,” remembered Shipfitter Art Sacco of LST 480. “Soon our ship was ablaze…. Flames covered the whole deck; we couldn’t see the bridge. I made everyone jump over the port side and swim under the burning oil to get to shore.”

Unfortunately, just because a man managed to reach shore did not mean he was safe. Immediately opposite Tares 8, 9, and 10 was the parking area for the LVTs and DUKWs, and beyond that a large sugar cane field. The fleeing men who reached shore, wet and covered with fuel oil, found it hard to scramble up a steep embankment to reach the amphibious vehicle park. Then, while some men sought refuge behind the parked amphibians, most took off through the cane fields. “The cane had been cut, leaving stubbles about six to eight inches high that were cut at an angle and sharp,” recalled Marine Harry Pearce. Most of the men had removed their shoes prior to jumping overboard. “It cut our legs and our feet all to pieces,” Pearce added.

In addition to their feet, the men also had to worry about their heads. “You see,” wrote S1/c Walter Slater, “a lot of guys went up through the sugar cane fields, and that’s where a lot of them got killed. Because the shrapnel, when the explosions would go off, it would go up high in the air, and there’d be big chunks of sheet metal flying, spiraling, and coming down, showering, and it would mushroom out.” More than a few men were killed when parts of the exploding ships hit them and killed them in the cane field. At least two Marines had their legs severed by flying jeep or truck engines.

Near 4:30 pm, when it was reported to the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard that the exploding ships were drifting south toward the Naval Ammunition Depot and the cargo ship Joseph B. Francis, three PT boats from Motor Torpedo Squadron 26 were dispatched from East Loch toward West Loch with orders to torpedo and sink, if need be, any drifting ship that might reach the depot. Within minutes, the three fast plywood boats were racing out of East Loch toward the growing danger in West Loch.

After LST 69 had hit LST 480 and set her afire, the two abandoned ships drifted about 200 yards past the Tare 10 pilings before a courageous tugboat crew rushed in and shoved LST 480 aside, stopping her southward drift. Around 4:50 pm, LST 353, which was still carrying LCT 963 on her deck, sank about 70 feet east of the Tare 10 pilings. Shortly thereafter, LST 39 stopped drifting, perhaps fouled in the wreckage of 353. With her bow doors open, ramp down, and a pair of pontoons on either side of her hull, LST 39 continued to burn.

Only three ships were still moving, LSTs 69, 43, and 179 carrying LCT 961. All three were bearing down on the ammunition depot and the Joseph B. Francis. The ammunition-laden merchant ship had remained in place for more than an hour as civilian stevedores and naval personnel hurried to unload over 3,000 tons of explosives. At 4:20, with 350 tons remaining and the burning ships drifting nearer, the decision was made to move the merchant to Middle Loch. As she was leaving, a huge explosion aboard one of the drifting ships pelted her top deck with white phosphorous shells, sending at least one shell into an open hatch. Seconds later a fire started. Only the quick action of the crew prevented another ship from exploding.

At 5:05 pm, while Joseph B. Francis was making her way up the main channel toward Middle and East Loch, one of the phosphorous shells reignited, sending flames and black smoke billowing out of the forward bay. Fearing a massive explosion from the 350 tons of unloaded ammunition, the Navy Yard started moving ships out of the way. At 5:20 the escort carriers USS Long Island and USS Copahee were ordered to get out of East Loch immediately. Two minutes later, however, the skipper of Joseph B. Francis reported, “Present fire out.” After two Marine Corps fire inspectors confirmed the report, orders were issued to the escort carrier crews to stand down.

Back in West Loch, the three burning LSTs continued drifting toward the ammunition depot. Just about the time the three PT boats reached the scene of the disaster, Navy tugboats, which had rushed in from Middle and East Loch, and fire tugs from as far away as Honolulu arrived in West Loch. Rushing into the maelstrom despite the apparent danger from the burning ships, the crews of the small but powerful boats went to work stopping the drifting vessels or putting out the flames while men in smaller craft continued to rescue people in the water.

Coast Guard fireboat X1426, commanded by Coxswain Lindel C. Jones, entered West Loch and was immediately stopped by a small boat carrying Vice Admiral Turner, who had rushed over to see what was happening to his precious invasion craft. “The admiral directed each boat to a certain area,” Jones recalled. “He sent a couple of boats to the ammunition dock and sent us to the center of the loch.” Remembered Marine Corps Colonel Robert Hogaboom, “At great personal danger, [Turner] personally supervised the operation until the fires were suppressed.”

While several of the tugboats and fireboats fought to suppress the fires on the three drifting LSTs and to stop their southward movement, others rushed over to help the three remaining ships from Tare 8 and the three high-speed transports moored at Tare 7. Although upwind from most of the flaming debris that had been thrown into the air by the explosions, the three old converted destroyers had become engulfed in the flames from the burning water. Only the quick actions of the tug and fireboat crews saved the three APDs from becoming victims of the West Loch disaster.

Sometime near 6 pm, with the PT boats still standing by, the three drifting ships suddenly came to a stop about 500 feet north of the Naval Ammunition Depot and the two anchored barges loaded with additional ammunition. “One of the LSTs that was burning was being driven by the current and wind directly into the ammunition depot,” recorded a witness. “Just before it reached the dock … the brake burned and released the anchor. This prevented the vessel from being blown into the ammunition depot.” When the first ship stopped, the second got fouled on the first, and the third got fouled on the first two. All three had stopped but all three continued to burn and explode. And the tugboat and fireboat crews continued to risk their lives.

“One fireboat disappeared into the fire several times,” wrote Marine Bill Simpson aboard LST 224, which had moved into the shallow back bay area. “Each time it backed out with its rope bumpers smoking or on fire. Finally, it went into the holocaust one more time, and this time it was never seen again.” The small seaplane tender USS Swan, capable of fighting fires, was severely damaged while trying to extinguish the fires on LST 480, the last ship to catch fire. “[Our skipper] brought the bow against the LST and tried to push it over in the water,” reported Signalman Charles E. Schiering. “There were two Navy men on that LST, and before [we] could get them off, it exploded, killing the two men and injuring several crew members of the Swan.” Heavily damaged and with several men injured, Swan left West Loch, hobbled into the Navy Yard for repairs, and spent the next six weeks in drydock.

For the next several hours the tugs and fireboats fought valiantly to control the fires in the six burning LSTs. The burning ships had become separated into two groups. LSTs 39, 353, and 480 near Tares 9 and 10, and LSTs 43, 69, and 179 in mid-channel about 500 feet northwest of the ammunition depot. In the latter group, 43 eventually capsized. When she did, one of her two pontoons, which was aflame, came loose and began drifting toward the moored ammunition barges. Fortunately, some yard tugboats rushed in and towed the two barges deeper into the shallow back bay while a few fire tugs doused the wayward pontoon.

By late evening the authorities had the disaster under control and the other ships out of the danger area. As the six ships continued to burn, dozens of firefighting boats, tugs, and harbor patrol craft dotted the surface of West Loch. The burning oil on the surface of the loch continued to be a menace to the rescue craft, while a heavy coating of unignited fuel oil and gasoline lodged under one of the piers near the ammunition depot. Firefighting teams went to work with hoses to break up the heavy sludge and keep it from igniting until the ebb tide carried it out of the area.

Throughout the night the firefighters doused the burning vessels from boats and from shore aided by six portable lighting sets that managed to turn night into day. At 5:10 am on Monday, May 22, 1944, as the sun began to brighten the eastern sky, the Pearl Harbor signal tower reported, “Fire and smoke still visible at Tare 8.” It was the last report containing any mention of fire or smoke. More than 14 hours after the initial explosion had erupted aboard the forecastle of LST 480, the West Loch disaster came to an end. At 7:15 am, the duty officer in the signal tower entered into his logbook, “Sandwiches and coffee for 50 men sent to Tare 8.”

Within 30 minutes of the first explosion on LST 353, three investigators from the Navy Intelligence Unit arrived at the Naval Ammunition Depot. With an invasion in the offing and the destination still unknown to most officers and personnel, the three officers were hoping to gather all “maps, papers, and secret and confidential documents” that might indicate where such an invasion would occur. Over the next few weeks, the men collected hundreds of documents and found enough “secret, confidential, and restricted publications” to fill “two large packing boxes.” No one knew, however, how much was not found and whether any vital information on the upcoming invasion had leaked. Only time would tell.

The gruesome task of gathering and identifying the dead began with first light on Monday, May 22. Coast Guard Coxswain Jones took his fireboat up to the burned-out bow of one of the LSTs and anchored on the open lowered bow ramp. “The ship was completely gutted,” Lindel remembered, “and there were dead bodies all over the ship … they never had a chance.”

That same morning Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, ordered a court of inquiry to look into the West Loch disaster. Three days later, while the court was in full session, Nimitz issued a press release to explain what had occurred on May 21.

Historian Howard Shuman noted, “At least 250,000 people on ships and ashore at Pearl Harbor and tens of thousands more from Honolulu to Ewa saw the black smoke and fires and heard the blasts at West Loch. The disaster was not unknown.”

Trying to downplay the disaster, Nimitz issued the following statement: “An explosion and fire which occurred while ammunition was being unloaded from one group of landing craft moored together in Pearl Harbor on May 21, 1944, resulted in destruction of several small vessels, some loss of life, and a number of injuries. A court of inquiry has been convened….” Nimitz had put a beautiful little spin on a devastating accident.

Fearing that word of the disaster would leak to the Japanese, a censor order was placed on the entire invasion force. As ordered by Admiral Nimitz, it was against regulations to talk about the disaster to others, including men from your own ship, or to write about it in letters home or elsewhere. William Wright, Jr., had been at paymaster school during the disaster but rejoined his ship just prior to the invasion. “I knew nothing about it until a long time later,” he recalled. “I didn’t even hear anybody talk about it among themselves. I guess they were threatened.”

All of the official information and documents pertaining to the disaster, including the official court of inquiry transcripts and testimonies, were classified as top secret and stored away until January 1, 1960. Author A. Alan Oliver noted the ramifications of such a classification in a magazine article: “In the Navy’s divine wisdom, clamping a TOP SECRET status on the tragedy caused much evidence that might have been of importance to be lost because of the interval of time before the incident was declassified and made public in 1960—16 years after its occurrence….”

The Navy court of inquiry wrapped up its hearings on June 12 and submitted a detailed report to Admiral Nimitz. Although any conclusive evidence was lacking, the court decided that the cause of the explosion was the detonation of a dropped mortar shell aboard LST 353. The court also found that the single detonation was so damaging because of “the stowage of gasoline in the immediate proximity of high explosive ammunition” and the “nesting of numerous combat loaded vessels at one berth.”

As far as major material losses, the court determined that six LSTs had been completely destroyed, three LCTs had been lost, and 17 LVT amtracs had been lost inside one LST and eight 155mm howitzers had been destroyed inside another. Two more LSTs has been so severely damaged that they were deemed too unsafe to make the 3,200-mile trip to Saipan.

In a monumental effort to replace his losses, Nimitz transferred several LSTs earmarked to transport garrison troops to the battle area to frontline duty. Eventually, the Navy found 11 alternate LSTs to replace the eight that were lost during the West Loch disaster. Although the LST fleet was scheduled to leave Hawaii on May 24, the departure was delayed one day and the vessels left port on May 25, making up the lost day up en route and arriving off the Saipan beaches on the preplanned invasion date of June 15, 1944. It was a fanciful bit of scurrying, but Nimitz and his staff had pulled it off.

The casualty count for the West Loch disaster was officially placed at 163 killed and missing and 396 injured for a total of 559. To a man, the survivors are skeptical of that number. Lieutenant Phil Kierl from LST 480 wrote, “There were reports circulated that total casualties exceeded two thousand.” PhM2/c William C. Johnson of LST 69 managed to get an uncensored letter home a few days after the disaster. He wrote, “They have estimated the loss of men at one thousand…. I saw plenty of dead, fellows with their arms and legs off and plenty of them nervous wrecks.” Seaman 1/c Walter Slater called 163 dead a conservative number. “I think 1,400 is a closer figure,” he said.

It was stated that the Marine Corps alone had 193 men killed and injured. However, Major Carl W. Huffman, who wrote the Marine Corps historical monogram on the invasion of Saipan, reported, “The Second Marine Division lost a total of 97 men and the 4th Marine Division 112 in the disaster.” The Marine Corps total, therefore, was actually 207. If the Navy had made a mistake in calculating the loss of personnel among its Marines, which had fewer bodies aboard the different ships at the time of the disaster, could it also have miscalculated the loss among Navy personnel?

Although Admiral Nimitz generally agreed with the findings of the court of inquiry, he decided to modify one finding. The court felt that the cause of the explosion was a mishandled mortar shell, but Nimitz wrote, “There is some evidence which might lead to the opinion that the initial explosion could have been caused by gasoline vapor.” The cause of the initial explosion was almost certainly careless smoking.

One step above Nimitz was Admiral Ernest J. King, commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet. When King read the report he saw red. “The organization, training, and discipline in the LSTs involved in this disaster leave much to be desired,” he wrote. “The lack of proper understanding and compliance with safety precautions when handling ammunition and gasoline, particularly in LST 353 where the first explosion occurred, is also noted. It is perfectly apparent that this disaster was not an ‘Act of God.’”

A survey was soon made to find several different loading and mooring spots for LSTs in the area. The survey found a number of new spots outside West Loch that would “permit spacing the LSTs in loading berths sufficiently to prevent fires from quickly spreading to adjacent vessels in case of fire or explosion.” The survey also suggested that no more than three ships be nested alongside one another at the mooring dolphins in West Loch.

In response to the suggestions of the court of inquiry, the Navy Department equipped “numerous tugs and vessels as fireboats for the protection of harbors and anchorages.” Fifty-two fire protection consultants were trained to “assist ships during periods of availability in reducing shipboard fire hazards, inspect firefighting equipment, and advise Commanding Officers of the latest firefighting practices and techniques.” By the end of 1944, there were 11 Class A and 15 Class B fire schools established at several Navy bases.

On July 17, 1944, another 320 sailors and civilians were killed and another 390 wounded in an explosion and fire that occurred during the loading of ammunition aboard a ship at Port Chicago, near San Francisco. The West Loch disaster and the Port Chicago explosion led to significant changes in the way the Navy handles ammunition. The Navy no longer moors ships in large nests, and all ammunition handlers now undergo specified training and certification before touching live ammunition. Additionally, modern munitions have been designed to make them much safer to handle.

The loss of life at West Loch did not end on May 22, 1944. On February 17, 1945, during salvage operations around one of the sunken LSTs two divers became trapped under a shifting piece of steel while working at a depth of 40 feet and in mud 20 feet deep. Plunging into the pitch-black water, Boatswain’s Mate 2/c Owen Francis Patrick Hammerberg, a Navy diver, rushed to their assistance. “Despite the certain hazard of additional cave-ins and the risk of fouling his lifeline on jagged pieces of steel imbedded in the shifting mud,” he managed to free one diver and then continued working toward the second.

For several hours Hammerberg stayed beneath the water, digging a shaft beneath the sunken LST with a water jet, washing away the “oozing subterranean mud in a determined effort to save the second diver.” Miraculously, he managed to reach the second man, but while trying to remove the diver a second piece of metal broke loose from the bottom of the LST. Shielding the other diver, Hammerberg took “the full brunt of terrific pressure on himself.” Although both men were eventually rescued and brought to the surface, Hammerberg died in agony 18 hours later.

For his unselfish actions, Hammerberg was awarded the Medal of Honor. His citation reads in part, “His heroic spirit of self-sacrifice throughout enhanced and sustained the highest tradition of the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life in the service of his country.”

So had many others during the West Loch disaster of May 22, 1944.

Gene E. Salecker is a retired university police office who teaches eighth grade social studies in Bensenville, Illinois. He is the author of four books, including Blossoming Silk Against the Rising Sun: US and Japanese Paratroopers in the Pacific in World War II. He resides in River Grove, Illinois.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments