By David H. Lippman

Both sides needed reinforcements.For the Japanese and the Americans in October 1942, the battle for Guadalcanal was turning into a bottomless pit, demanding more and more scarce resources—in the air and at sea and, most importantly, on the ground. Control of the malarial, jungle-clad island and its airfield might determine the fate of the war in the Pacific.

The problem was that neither the Japanese nor the Americans had the resources. Both nations were trying to wage the South Pacific war on the cheap—the bulk of Japan’s ground forces were committed to the endless war in China, and the United States was committed to the “Germany First” policy, which made the war in Europe the first priority. Both sides lacked troops, transports, planes, and basic supplies.

Nevertheless, as the U.S. Marines and Japanese Army units on Guadalcanal became exhausted from heavy combat and rugged conditions, it was more imperative than ever to resupply and reinforce the troops—on both sides.

As September turned to October, the Japanese moved first. The local commander, Rear Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, using destroyer transports, ordered the delivery of 10,000 men of the tough 2nd Infantry Division to Guadalcanal’s Cape Esperance in eight nocturnal runs down the channel between the Solomon Islands chain, a route known to the Americans as The Slot, in a measure the Japanese called the Ant Transportation, but known to Americans then and forever as the Tokyo Express.

The Americans did not waste time in reacting. Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief Pacific, ordered his top sailors on the scene to take swift action.

The task fell to Rear Admiral Norman Scott, an aggressive sailor, Indiana native, and 1911 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, where he was a champion fencer. He had been executive officer of the destroyer Jacob Jones when it was sunk by a German U-boat in 1917, naval aide to the president, commanded the heavy cruiser Pensacola, and had served in the office of the Chief of Naval Operations in 1941 where, according to Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, he “made things so miserable for everyone around him in Washington that he finally got what he wanted—sea duty, and his rear admiral’s stars.” He had been near but not present at the Savo Island debacle and learned from the disaster.

Scott’s task was twofold: ensure that the U.S. Army’s 164th Infantry Regiment and its 2,837 men, along with the ground crew of the 1st Marine Air Wing and assorted supplies, reached Guadalcanal safely to reinforce the Marines and attack the next convoy of Japanese reinforcements themselves. His orders: “Search for and destroy enemy ships and landing craft.”

On October 9, 1942, the 164th headed from New Caledonia for Guadalcanal in two battered transports, the McCawley (“Wacky Mac”) and the Zeilin, shepherded by eight destroyers. Scott’s Task Force 64 arrived south of Rennell Island the same day and readied for battle.

Task Force 64 consisted of two heavy cruisers, the San Francisco and Salt Lake City, two light cruisers, the Boise and Helena, and five destroyers, Farenholt, Buchanan, Laffey, Duncan, and McCalla.

They were a well-trained group in comparison to the force that had been annihilated in August at Savo Island. Under Scott’s leadership, Task Force 64 had done intensive night gunnery exercises, with men enduring general quarters from dusk to dawn. Scott had also laid down a carefully drawn battle plan. His ships would steam in column with destroyers ahead and astern. The tin cans would illuminate the Japanese targets with their searchlights, fire torpedoes at the largest enemy vessels, guns at the smaller ones, and the cruisers would open fire whenever they spotted an enemy ship. Cruiser floatplanes were to illuminate the battle area.

Despite the intense training and tight plans, Scott’s force had weaknesses. San Francisco had done poorly in gunnery exercises and had been used for convoy escorting duties, complete with a depth charge rack hammered on her stern. That was not too useful, as San Francisco lacked sonar. The depth charges were a potential fire hazard in battle. Boise also had a questionable history. She had missed a major battle in the Dutch East Indies when she ran aground.

More importantly, the two heavy cruisers operated the early SC (“Sugar Charlie”) radar, while the light cruisers sported the more effective and modern SG (“Sugar George”) radar among the first American ships to do so. Worse, Scott, like other admirals of the time, was not overly impressed with radar, preferring the tried and effective night optics of scopes and searchlights. As a result, Scott hoisted his flag on San Francisco, which offered flag quarters, as opposed to the smaller cruisers, which did not. He accepted reports that the Japanese had receivers that could detect SC radars in use. So he ordered them shut off during the approach to action and only used the SG radars and narrow beamed fire control radars to supplement his lookouts. Perhaps most critically, in night naval battles in the Pacific to date, the Japanese had sunk eight Allied cruisers and three destroyers without losing a single ship.

Nonetheless, Scott was ready. On October 9-10, he made tentative advances to Cape Esperance but turned back when aerial reconnaissance and codebreakers reported no suitable Japanese targets.

There was good reason for that. Japanese convoys down The Slot were being delayed by American bombers based on Guadalcanal’s Henderson Field, which irritated Mikawa. He complained to Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka, who headed the 11th Air Fleet at Rabaul. Kusaka said he would neutralize Henderson Field if Mikawa would run the Express.

On October 11, some 35 Japanese bombers and 30 fighters attacked Henderson Field but only managed to bomb the jungle. The Japanese lost four Mitsubishi Zero fighters and eight bombers. But they drew off the Americans, giving the Japanese ships a break to head south.

However, the naval movements caught the eye of patrolling Boeing B-17 bombers of Colonel L.G. Saunders’ 11th Bombardment Group, and they reported two cruisers and six destroyers racing down The Slot. The bombers’ messages went to Scott and his command. On Helena, Ensign Chick Morris, the radio officer, wrote about “a steady, chattering stream that kept the typewriters hopping.”

The oncoming force was actually two groups. One was the “Reinforcement Group,” consisting of the fast seaplane tenders Nisshin and Chitose and five troop-carrying transports. The seaplane tenders’ aircraft had been removed in favor of four 150mm howitzers and their tractors, two field guns, and 280 men, which jammed the two ships’ hangar spaces. The other force was a veteran group of three heavy cruisers, Aoba, Kinugasa, and Furutaka, and two destroyers, Hatsuyuki and Fubuki. Except for Hatsuyuki, all ships were the victors of Savo Island. Called the “Bombardment Group,” their mission was to escort the reinforcements and then treat Henderson Field to a dose of heavy shellfire with their guns.

In command of this force was Rear Admiral Aritomo Goto, who graduated from the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1910, 30th in a class of 149. He had commanded destroyers, served on battleships, and headed the second and successful invasion of Wake Island in 1941. It was a powerful group of well-trained sailors with victorious experience in night battles. Their job was simple: get the reinforcements in so that the Japanese 17th Army could attack Henderson Field on October 22, backed by more powerful naval and air forces.

Because of this, the Japanese cruisers and destroyers were loaded with high explosive ordnance useful for blasting ground troops and installations instead of armor-piercing ordnance needed to rip through ships’ steel hulls.

For once, the Americans had the intelligence advantage—the Japanese knew nothing of Task Force 64, and Goto’s force steamed southeast in utter ignorance of its enemy, in antisubmarine formation with Aoba and Goto in the lead, Furutaka behind, and Kinugasa in the rear. Fubuki stood guard on the starboard side with Hatsuyuki to port.

Task Force 64 steamed northeast in battle line with the destroyers Farenholt, Duncan, and Laffey in the lead. Behind them were San Francisco, Boise, Salt Lake City, Helena, Buchanan, and McCalla. Scott’s plan was to intercept the Tokyo Express west of Guadalcanal, cross the T of his advancing enemy, lay down a broadside of torpedoes and shells, and then countermarch—all the ships turning on one point and staying in formation—and double back to deliver a second dose of fire. Scott sent this plan by signal flag to the other ships, and Chick Morris and his fellow junior ensigns—they called themselves the Junior Board of Strategy—took a break from the tension to stand on Helena’s forecastle, study the plans, analyze their implications, and wonder how they would stand the fight.

Amid sunset colors, Morris wrote, “It was good to stand there and watch the ships of our formation steaming through that placid sea. And I was not alone. Other men were thinking the same thoughts. Some were sitting around anchor windlasses. Others were parked on the bitts, quietly ‘batting the breeze.’ One man was asleep on the steel deck, and another, nearby, was deep in a magazine of Western stories.”

Evening saw a new moon behind cirrocumulus clouds and a seven-knot wind as Task Force 64 took up its northeastward course. Everyone was now at general quarters. Chick Morris described his men as “dumpy and fat in fireproof goggles, steel helmets, Mae Wests and gloves; they resembled visitors from Mars.”

To reduce the possibility of their catching fire, Scott sent all but one of each cruiser’s seaplanes to the American seaplane base at Tulagi. He launched the remaining planes to locate the onrushing enemy, and San Francisco’s plane did so. So did the cruiser’s radar—one of the operators made the report, and his officer said it must be the islands the ship was passing. The radarman answered, “Well, sir, these islands are traveling at about 30 knots.”

At 2330 Salt Lake City’s search radar made the definitive call: three clusters of steel on the water to the west and northwest—Goto’s cruisers. Scott ordered his countermarch immediately, radioing his commanders, “Execute left to follow—Column left to course 230.”

And with that simple order, Scott’s plan disintegrated. The three lead destroyers turned on the appointed dime and stayed in column, heading south. But San Francisco’s skipper, Captain Charles H. “Soc” McMorris, one level up from Scott’s bridge, did not get the order. He turned immediately.

Behind San Francisco, Captain Mike Moran of Boise was stunned. Should he continue as ordered or follow centuries of naval tradition and follow the flagship? The first move would leave his cruiser on its own. The second move would cut the three lead destroyers on their own. Either way, the formation would disintegrate. Figuring that keeping more of the formation together than some of it was the main goal, he turned behind San Francisco. So did the rest of the column.

At that moment, Goto’s ships emerged from two hours of rain squalls and into American radar range. All the American ships started lighting up their radars to lock on the Japanese targets and open fire immediately. But on San Francisco, Scott did not know what was going on. He had no idea where his lead destroyers were, and his ship lacked SG radar to find them. There was a danger he might fire on his own vessels.

Scott immediately radioed Captain Robert Tobin, leading the destroyer squadron from Farenholt, asking “Are you taking station ahead?” Tobin replied, “Affirmative. Moving up on your starboard side.”

That meant that three American destroyers were steaming between his cruisers and the Japanese ships. Scott signaled back: “Do not rejoin, until permission is requested giving bearing in voice code of approach.”

Scott’s ships could not open fire, even though their lookouts could see the Japanese pagoda forecastles and bows cutting through the water. “What are we going to do, board them?” a chief petty officer growled on Helena. “Do we have to see the whites of the bastards’ eyes?”

That ship’s skipper, a Navy Cross holder named Gilbert Hoover, had the answer. He had served in the Bureau of Ordnance and led destroyers at Midway. He understood the value of both radar and time. Over Talk Between Ships (TBS) radio, he signaled “Interrogatory Roger” to Scott, the standard request for permission to open fire. Scott signaled back, “Roger,” the message to open fire. The problem was that Navy Signal Book regulations said that a voice signal of “Roger” merely meant “I have received your message.” Was Scott giving permission to open fire or merely acknowledging the message? Just to be sure, Hoover made the signal a second time and got the same response.

With that, Hoover opened fire with his 15 6-inch guns, a full broadside, hurling armor-piercing shells across the ocean and spent cases onto turret decks. Helena’s gunnery director called for automatic continuous mode to maintain the barrage. Chick Morris described the scene: “Now suddenly it was a blazing bedlam. Helena herself reared and lurched sideways, trembling from the tremendous shock of recoil. In the radio shack and coding room we were sent reeling and stumbling against bulkheads, smothered by a snowstorm of books and papers from the tables. The clock leaped from its pedestal. Electric fans hit the deck with a metallic clatter. Not a man in the room had a breath left in him.”

On Salt Lake City, Captain Ernest J. Small was reluctant to open fire, but he had a lookout chosen especially for his night vision, who yelled into his phone to the bridge, “Those are enemy cruisers, believe me! I’ve been studying the pictures. We got no ships like them.”

That did it. Salt Lake City joined the bombardment, firing at Aoba, 4,000 yards away, reporting “all hits.” Boise opened up next, with Captain Moran yelling at his gunnery officer, Lt. Cmdr. John J. Laffan, “Pick out the biggest and commence firing!” Boise’s directors were also trained on Aoba, and more shells whistled at her.

Down below on Boise, in Damage Control Central, Lt. Cmdr. Tom Wolverton, the damage control officer, relieved the tension of open-fire gongs and vibrations by recalling his nine-year-old son’s first rollercoaster ride and reaction, sharing it with his men: “Daddy, I want to go home now!”

By now all of Scott’s ships were blazing away. Radar obviated the prewar need to fire many ranging shots. The first Boise broadside hit a heavy cruiser. An “up 100” correction did even more damage. The Japanese had no time to react.

Neither did the Americans, really, as Scott still wondered and worried where his three missing destroyers were. But his sailors enjoyed the spectacle. On McCalla, Ensign George B. Weems “felt a wildly exultant joy in watching us let them have so much at such murderous range. If you stop and think—2,500 to 3,000 yards is point-blank range for big guns. You can hardly miss even if you wanted to!”

To Weems, the enemy ships looked like “the most dramatic Hollywood reproductions…. I saw two that worked about like this: (1) pitch darkness, (2) stream of tracers from our ships by star shells, (3) series of flashes where hits were scored, silhouetting of ships by star shells, (4) tremendous fires and explosions, (5) ship folds in two, (6) ship sinks. All in all, a much better performance.” To the Americans who had endured the humiliations—at least in the news—of Pearl Harbor and Bataan, it was revenge. Had the Americans been aware that the three cruisers had helped sink 1,000 of their shipmates at Savo, it would have added to the jubilation.

On the Japanese side, the impact of the barrage was dreadful. Aoba was hit at least 24 times in a matter of minutes. The bombardment punched out her two main forward turrets, her main gun director, several searchlight platforms, her catapults, and several boiler rooms. The cruiser’s foremast toppled down.

Goto seemed perplexed by the situation. As his ship veered to starboard to avoid further punishment, he signaled “I am Aoba,” probably thinking that he was a victim of “friendly fire.” He yelled out “Bakayaro!”—Japanese for “stupid idiots!” just before an American shell smashed open the bridge, mortally wounding him. Aoba’s skipper, Captain Yonejiro Hisamune, ordered a smoke screen, and the battered heavy cruiser, 79 of its men dead, staggered away from the scene.

Scott was worried about friendly fire, too. He had good reason to fear that the barrage he had unleashed was killing his own men. He climbed up the ladder from the flag bridge to the main bridge to shout the order, “Cease firing, all ships,” which astonished everyone in sight.

But the order was transmitted, and all ships except Boise obeyed. Moran was certain his ship had Japanese vessels in his sights, and he ordered, “Rapid fire continuous.” Then he leaned over the rail of the bridge wing, and said, “Begging your pardon, Admiral.”

Meanwhile, Tobin radioed Scott, saying, “We are on your starboard hand now, going up ahead.” Scott kept repeating the cease-fire order on TBS, battling buck fever among excited sailors. “It took some time to stop our fire,” Scott wrote. “In fact it never did completely stop.”

Discipline was under strain—on Farenholt, a gun captain named Wiggens would not obey the cease-fire order, even when the skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Eugene T. Seaward, repeated it. Wiggens’ wife was a Chinese national he had been forced to leave behind in Singapore when the Japanese attacked it in December. Now he had recently learned that the Japanese had killed her. “Every time he could train on that huge Japanese battle cruiser (at point-blank range) he would let go with another round,” wrote Ford Richardson, a talker for Farenholt’s gunnery officer. “Wiggens went wild. Crazy wild. He hated Japs with a passion.”

Other Americans were puzzled on this wild night, particularly the skippers and officers on the three destroyers that had gone ahead. They wondered why San Francisco made a strange turn and had taken all the other ships with her. Tobin’s main concern was staying out of the crossfire between American and Japanese lines. He saw Helena and steered right standard rudder to stay clear of her fire.

Scott called Tobin on TBS and asked the commander of Destroyer Division 12, “How are you?” “Twelve is okay. We are going up ahead on your starboard bow. I do not know who you are firing at.”

Scott ordered Tobin’s ships to display their recognition lights. The three tin cans flashed the required green-and-white for a few moments. That was enough for Scott. He ordered his ships to resume firing.

The next broadside caused tragedy. In Farenholt’s main battery director, Ford Richardson “stood there transfixed watching the pyrotechnics. Our cruisers on one side of us were firing at the Jap ships on the other side of us.” He dropped down inside the director. “At that very instant, we were hit by a 6- or 8-inch shell at the cross arm of the foremast, some 25 feet over my head!”

The airburst rattled Farenholt’s decks, and shrapnel tore through the rangefinder, slicing through a man standing forward of it. The man was passed down to Richardson, and he stopped the wounded man’s bleeding by stuffing a T-shirt into his shipmate’s gaping wound and using his belt as a compress.

The hit also sliced Farenholt’s radar antenna, exploding spectacularly and sending fragments that cut through a torpedo’s air flask. The fish launched and slammed into the base of the destroyer’s forward stack. The impact activated the torpedo’s motor, and it howled for a while before burning out. Amazingly, it did not explode.

Four more American shells and near misses shredded Farenholt, coming from Salt Lake City and San Francisco. One hit the waterline, and she took a list to port and withdrew from the battle.

Duncan took a pasting from her shipmates and her enemies, too. The destroyer was named for a New Jersey-born hero of the 1814 Battle of Lake Champlain, Silas Duncan. American shells smacked her forward fire room while Japanese shells blasted her forward stack, gun director, radar plotting, and radio rooms, killing everyone in the latter compartment, and hit her No. 2 ammunition handling room, which set the gunpowder ablaze.

The skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Edmund B. Taylor, lost steering control and found his ship reeling out of the battle, staggering in circles, her forecastle and bridge blazing like a torch, speed dropping to 15 knots. With her phones out, the engineers had no idea what was going on above them. Neither did the bridge crew, who only saw fires all around them and were trapped in a bridge full of asphyxiating smoke and steam. Taylor ordered his men to abandon ship in the face of the conflagration and get the wounded into life rafts, personally joining in those efforts.

Unfortunately, nobody could hear his order amid the smoke. But Assistant Gunnery Officer Ensign Frank Andrews, seeing that “something was wrong,” left his battle station to find the decks deserted, the ship smothered in flames, out of control. Believing his skipper was dead, he sent a man down to the forward engine room to tell Chief Engineer Lieutenant H.R. Kabat of the situation. Believing himself the senior officer on board, Kabat took command and ordered Duncan steered into shallow water to prevent her from sinking.

Duncan’s sacrifice was not in vain. Just as she was hit, she cut loose with a torpedo salvo at a Japanese cruiser. “Almost immediately she was observed to crumble in the middle, then roll over and disappear,” Taylor wrote. Duncan’s target was probably the destroyer Fubuki, which did sink around that time.

The torpedo attack paid great dividends, punching holes in the heavy cruiser Furutaka as she turned to starboard to follow the flagship Aoba, hitting her No. 3 turret and the port torpedo tubes, cooking off her Long Lance torpedoes.

Amid this incredible din, midnight and eight bells struck on all the ships, turning the battle over to October 12, and the Japanese were finally beginning to recover from the surprise. Kinugasa’s skipper, Captain Masao Sawa, realizing the gravity of the disaster, put his ship to port to maneuver away from the blazing Furutaka and the American battle line with Hatsuyuki following.

All the Japanese ships hurled shells at the Americans, lacking time to send their torpedomen to their stations. The Japanese time-fused high-explosive ordnance, set for airburst, could not punch through plate armor, but it did plenty of damage. One airburst exploded high amidships over Salt Lake City, killing four sailors and wounding 16 more.

But some shells hit home. Boise was struck by an 8-inch shell that dented and ruptured her side plating, shattering junior officers’ country. Two smaller rounds blasted Moran’s sea cabin and turned it into wreckage. A clock was knocked from the skipper’s desk, shattering it at five minutes to midnight, forever denoting the time of impact.

During the firing lull, San Francisco’s radar spotted a blip closing to 1,400 yards on a parallel course. This was the destroyer Fubuki, and incredibly she seemed oblivious to reality. She was sending out signals with a hooded light before turning away. San Francisco slapped her in a searchlight beam, and her gunners spotted the distinctive double white bands on Fubuki’s forward stack that identified a Japanese destroyer. With that information in hand, San Francisco, Boise, and other American ships opened fire on her. Fubuki burst into flames and began to sink.

Now Scott realized that “some shaking down was necessary in order to continue our attack successfully.” He ordered fighting lights flashed and gave his ships 10 minutes to sort out his formation. Then he changed course to 280 degrees.

By now the only Japanese ship capable of fighting back was the undamaged heavy cruiser Kinugasa, whose torpedomen had finally reached their stations. At 0006, she cut loose with her powerful Long Lance torpedoes at Boise, and the American cruiser heeled to starboard, paralleling the wakes. One fish cleared the port bow while the other zoomed by the starboard side, missing Boise by about 30 yards.

As Boise and Salt Lake City were both using their searchlights, Kinugasa homed in on the lights. At 0009, the Japanese cruiser opened fire with a tight pattern of 8-inch shells that straddled San Francisco’s wake. Then Kinugasa aimed at Boise. At 0010, an 8-inch shell hit Boise’s number one barbette, crashed through a deck, landed in a turret stalk with its defective fuse hissing, and started a smoky fire. The turret officer, Lieutenant Beaverhead Thomas, pushed open the turret’s small escape hatch and ordered everyone out. He reported by phone to Commander Laffin, the gunnery officer, that he had abandoned station.

“The fuse hasn’t gone off yet,” Thomas said. “I can still hear it spluttering.” A second later the fuse and 250-pound shell went off, sending a blast through passageways, hatches, and vents, killing about 100 men.

The 11 survivors of Turret One reached the deck just as two more hits landed, one on Turret Three, just forward of and below the bridge, gashing the 6-inch guns and scattering shrapnel across the bridge. Another shell entered the water short of Boise.

This shell was one of Japan’s distinctive weapons, the 91 Shiki (Type 91), designed with a pointed ballistic protective cap that broke off on impact and enabled it to keep its ballistic properties underwater. It hit close enough aboard to keep swimming downward and penetrate the hull nine feet below the waterline. Incredibly, this hit seems to have been the only time during the entire war that the shell worked as designed.

The shell exploded in the forward 6-inch magazines, sending another wall of flame through the forward handling rooms and up the stalks of the two forward turrets, killing everyone in Turret Two. The fire flew up as high as the flying bridge, followed by a torrent of hot seawater, debris, smoke, and sparks. Following their training, firefighters hauled out heavy hoses to address the blazes.

Moran regained his feet and composure and realized his ship would fly apart in seconds from the various explosions. He ordered the forward magazines flooded, but the men at the remote control panel who could do so were all dead.

Fire raged in the main magazines of Turrets One and Two, setting the forecastle ablaze. “Smoke, debris, hot water, and sparks flew up well above the forward directors” and hurled Moran against a bulkhead. Watching from San Francisco, Scott feared Boise would sink.

As Boise blazed, she came to a halt, and Helena raced by her in the dark. Helena’s crew had gotten to know Boise’s crew well from both training and playing softball at the New Caledonia base, and the Helena sailors were enraged. “The battle had been a game until then,” Chick Morris wrote. Moran shouted at Helena, “Cruiser to starboard. Shift target!”

Lieutenant Warren Boles in Helena’s Spot One responded by telling his gunners, “Set ‘em up in the next alley. Pour it to ‘em.”

A magazine explosion was the greatest calamity a warship could suffer, and Moran was determined to save his ship. Firefighters tried to quell the blazes in the turrets but could not squeeze through the charred bodies in the hatches. A gunner’s mate named Edward Tyndal pleaded to enter a turret to find his younger brother Bill, who was in one of them.

Moran had to flood those forward magazines, but there was no way to do it. Then fate—and Japanese shells—took a hand. It was the devotion of the men now dead in the forward magazines who made sure there was a minimum of loose powder in those magazines and the popped holes in the hull that saved Boise from destruction. The Japanese shells that hit underwater let in waves of seawater that flooded all the forward hull spaces, including the magazines.

The power of the flood was such that the Boise’s crew thought their ship had been hit by a torpedo. Men in rescue breathers shored up bulkheads against the flood and set up pumps to push out the water.

The flood endangered the medical department, so they moved sickbay from the wardroom to the battle dressing station. A patient with a cast on his broken leg limped along on crutches. Another, who had endured appendix removal a few days before, climbed out of his hospital bunk and refused a stretcher saying, “Outta my way! I’m getting the hell out of here!”

On all the American ships, binoculars were trained on the blazing Boise, which appeared doomed. But her boilers and engines were intact, and with the fire out, Moran ordered flank speed, sheering out of battle line to port at a spanking 30 knots, outrunning another cluster of shells from Kinugasa. Boise’s after turrets maintained a steady barrage, and the ship fired more than 800 rounds in the battle.

To avoid Boise ahead, Salt Lake City turned hard right and threw the starboard engine into reverse to sharpen the turn, putting Small’s ship between Boise and the Japanese as a shield. The Japanese slammed an 8-inch shell into Salt Lake City’s starboard side, which exploded, dishing in the armored plating. Another shell penetrated the hull, shot through the supply office, and clanged against the fire room’s deck plating. There it exploded with a low-order blast. Nobody was hurt, but a lot of electrical cables were severed, a boiler disabled, and a fire started in the bilges, fed by 26,000 gallons of fuel oil from a ruptured transfer line. The fire blazed hot enough to warp one of the cruiser’s heavy longitudinal I-beams and buckle the armored second deck.

Salt Lake City came clear of Boise, rang up full speed, and trained its guns on an enemy cruiser three miles off its starboard beam. The amidships secondary guns fired star shells to illuminate the target, but the Japanese fired first, hitting Salt Lake City, knocking out her circuits. Steering control failed, and damage control reported fires forward. Small flooded his forward magazines as a precaution, transferred helm control to the emergency steering cabin, and closed throttles to the outboard engines, leaving the two inboard screws to propel the cruiser through the water.

With that flurry of firing, the Japanese began to withdraw. Goto’s chief of staff, Captain Kikunori Kijima, ordered a withdrawal as senior officer, while Goto lay dying on Aoba’s bridge. Then Kijima told his boss that he could die “with an easy mind” because two American cruisers had been sunk.

Actually, the only cruiser to be sunk that night was Japanese, and that was Furutaka. Half an hour after taking all her hits, she lost power. The destroyer Hatsuyuki nuzzled up to render assistance, but there was nothing left to do. Furutaka was hopelessly flooded. Captain Tsutau Araki ordered the ship’s ensign pulled down, the emperor’s portrait salvaged, and the ship abandoned. Araki himself went to his cabin to end his ordeal but found that his pistol and samurai sword had been taken from him. He climbed back to the bridge to tie himself to the compass pedestal but found no fasteners that could do the job. Araki’s executive officer, however, stood there pleading for Araki to survive. He was probably the man who removed the fasteners. The officer had a point. Tokyo had issued a letter saying that a modern navy like Japan’s could not afford valuable skippers committing seppuku out of pride when their skills were needed for future battles.

As the two officers argued the merits of the Bushido code, the rising sea engulfed the bridge and Araki found himself floating alongside the bow, alive, to his disgrace.

At 0228, Furutaka sank stern first with 258 crewmen aboard 22 miles northwest of Savo Island. The ensign ordered to save the emperor’s portrait did not accomplish his mission. He was killed by American shellfire. Furutaka was the first Japanese heavy warship lost to enemy guns in World War II.

The Americans were also coping with damaged and sinking ships while trying to reorganize. At 0016, Scott changed course to 330 degrees to press the enemy, but after a few more minutes of “desultory firing,” he decided he had had enough. The enemy was silenced and retreating while the American formation was broken. At 0020, he chose to retire with ships flashing recognition lights in the dark. That had interesting results. San Francisco’s portside lights did not come on, which bothered Lt. Cmdr. Bruce McCandless. Sure enough, two star shells burst overhead, illuminating the night, a sign of incoming fire from a friendly ship. San Francisco fired three green flares.

“The navigator pushed the button … harder. This time both sides lighted up,” McCandless wrote later. The flares impressed the fire control teams on the Salt Lake City, 3,000 yards to port. She was about to cut loose with a broadside when someone recognized the intruder as San Francisco, yelling, “Hold it! It’s the Frisco!” Salt Lake City held her fire.

“For this, we will be eternally grateful,” McCandless wrote.

At 0044, Scott warned, “Stand by for further action. The show may not be over.”

But it was. Now it was time to save ships and men. Boise had her forecastle fires out by 0019, but two turrets still blazed. Crewmen opened hatches of one and aimed in hoses, but bodies blocked the hatches of the other, so crewmen threaded hoses up the expended case scuttles. By 0240 all fires were out, and Boise’s holes plugged.

The rest of Task Force 64 located Boise at 0305. Scott wanted to head off at maximum speed, but Boise was nearly a cripple. Recovery and rescue teams were poking through the ghastly wreckage of the two forward turrets. They found some men alive, but nearly 90 percent were dead of asphyxiation or concussion. Moran slowed his ship to 20 knots to reduce sea pressure on his forward bulkheads.

Farenholt turned up, too, battered by friendly fire. Her crew tossed heavy gear—whale boat, depth charges—over the listing side and transferred fuel from port to starboard. They also ran portable pumps and a bucket brigade until her waterline holes were dry.

That left the sinking Duncan, out of action and immobile, drifting in aimless circles just northeast of the battlefield. A massive fire blazed below decks in the forward engine room. The after fireroom could not obtain boiler feed water. Steam power dropped rapidly. Lieutenant Wade N.H. Coley and Chief Water Tender A.H. Holt tried to run a boiler on seawater, pumped in by gasoline-powered handy-billy. It did not work. The medical officer pushed through heavy smoke to sickbay to procure needed drugs and was never seen again. Another group dropped over the ship’s side, watched Duncan slow to a stop, and swam back to assist in the fire fighting.

It was clear that Duncan could not survive. At 0200, the ship was abandoned. Crewmen hurled anything that could float into the water to help survivors. Fortunately for all, McCalla turned up at this time, and her skipper, Lt. Cmdr. William G. Cooper, approached warily, fearing that Duncan was a Japanese vessel. At 0300, he lowered a boat with a party under his executive officer, who examined the wreck and believed it salvageable. With that, McCalla headed off to find Boise, but her crew heard Duncan’s survivors yelling from their lifeboats, floater nets, and Mae Wests in waters filled with sharks. Generations of Solomon Islanders had made the area a hunting ground for sharks by setting their dead adrift.

McCalla began pulling Duncan crewmen out of the water just in time to avoid a concentrated shark attack, saving 195 officers and men. Some 95 members of Duncan’s crew went to the bottom when the destroyer sank around noon after a day of smoke and rumbling explosions. A fighter pilot flying guard over the wreck said her “bow end looked cooked.”

With that, McCalla steamed off to rejoin Scott’s force, but not before spotting some shaven-headed Japanese sailors floating in the water. McCalla threw them some lines, but most of the Japanese preferred sharks to survival. She only took aboard three sailors. However, the minesweepers Hovey and Trever, based at nearby Tulagi, did better on the 13th, saving 108 Japanese survivors.

The Japanese, however, made strong efforts to recover their own lost men, sending the destroyers Shirayuki and Murakumo to do the job. They pulled 400 shipmates from the water, but Murakomo was spotted by American dive bombers from Guadalcanal, which piled into her with bombs. She had to be scuttled. Another relief destroyer, Natsugumo, suffered the same fate.

Meanwhile, the triumphant but battered Task Force 64 cracked on its best speed to head home, covered by fighter planes that found the ships by the trails of oil the damaged ones leaked.

Scott’s ships reached Espiritu Santo on October 12. “As we pulled into harbor, we were a cocky bunch,” Laffey signalman Richard Haled recalled. “We wanted to paint a couple of cruiser and destroyer symbols on the side of our mount to let everyone know that the Laffey was a real fighting ship. We lost all fear of battle at that point, and getting away without a scratch while pounding the enemy meant that we were ready to win the war.”

As hands cleaned ships, they relived the battle. Chick Morris said they recalled “little things, remembered now in detail and passed from group to group, often distorted beyond recognition before they got very far. But it was good for the ship’s morale. Anything was good that contributed to the story of the enemy’s defeat.” McMorris sent 20 gallons of ice cream as “reparations” from San Francisco’s freezers to Farenholt in apology for the tragic mistake that killed three of her men and wounded 43.

The victory was a major boost to American morale. Until that point, every surface encounter between the Allied navies and the Japanese had ended in disaster for the Allies. But Cape Esperance was a clear-cut victory. The Japanese had lost the destroyer Fubuki and the heavy cruiser Furutaka, while the Americans only lost the destroyer Duncan. Worse, following the night clash Japan lost two more destroyers to American air attacks.

Human casualties favored the Americans, too. The Japanese lost 454 dead, 258 on Furutaka alone, and 111 prisoners. The Americans suffered 163 dead, 107 on Boise, and 125 wounded.

It was time for both sides to assess what went right and wrong. For the Japanese, it was a harsh and unpleasant task, having lost four ships and its pride of “invincibility” in night surface fighting. Despite Kijima’s claims of sinking two American cruisers, he was relieved. Furutaka’s shipwrecked Captain Araki divided blame between faulty Japanese air reconnaissance and his bosses, the desk sailors at 8th Fleet who did not understand the situation of the deck sailors—an old cliché. The battle was disheartening to the Japanese. One official source wrote, “Providence abandoned us…. The future looked bleak for our surface forces, whose forte was night warfare.”

Actually, the Japanese failures were a mirror of the American failures at Savo Island two months before—poor air reconnaissance, failure to have the ships ready for action, and being caught by surprise. Admiral Matome Ugaki, the chief of staff of the Combined Fleet, wrote in his diary that the cause of the debacle was carelessness and that Goto should have followed the Japanese proverb, “Treat a stranger as a thief.”

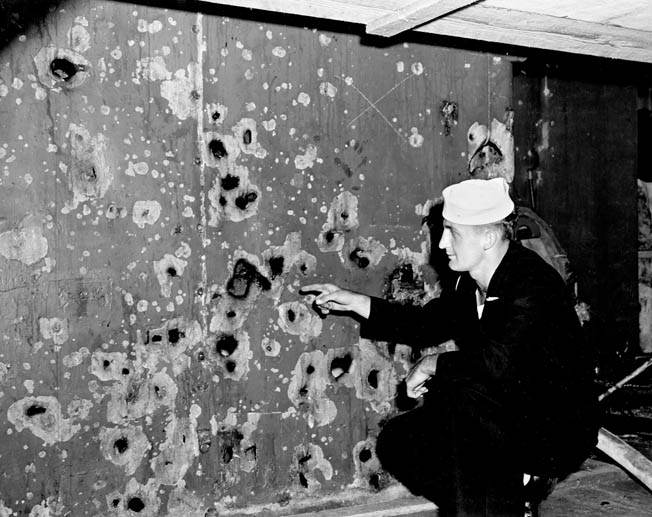

The Americans had their share of Monday morning quarterbacking to do, too. Scott’s force had done well, but Salt Lake City, Farenholt, and Boise were out of the game. Boise was headed all the way to Philadelphia for major repairs, where Navy public relations men would tout her as a “one-ship fleet” that had accounted for six enemy vessels in action, displaying her grinning crewmen and gruesome shellholes to impressed news reporters.

In his report, Scott credited his “crude night firing practices” for his success. Salt Lake City’s after-action report offered 39 paragraphs on everything from gunnery and fire control to ship handling, repairs, and communications, restricting telephone circuits to business at hand to avoid spreading uncertainty or panic … shifting targets during loading intervals … stretcher bearers being kept in darkened compartments or wearing night goggles to preserve their night vision.

Lost or overlooked in the analysis were the things that went wrong, which would have a harsh impact a month later in greater and more decisive naval battles. Scott’s formation was too densely packed, which worked against using a destroyer’s most effective weapon, its torpedoes. The reliance on recognition lights endangered American ships. The Americans needed to make better use of radar. Poor fire discipline had resulted in one American destroyer being sunk and a second gravely damaged by friendly fire. Poor communications caused Scott’s formation and plan to break up. These lessons went unnoticed and ironically would lead to Scott’s death a month later in the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, when he was killed on his ship’s bridge by an 8-inch shell from his old flagship, USS San Francisco.

A junior officer on Helena, Charles Cook, wrote the most cutting analysis of Cape Esperance later, calling the engagement “a three-sided battle in which chance was the major winner.”

In the greatest irony, while Cape Esperance provided Americans with a needed victory and its morale boost, the battle did little to change the course of the Guadalcanal campaign. The Japanese Reinforcement Group delivered its troops to Guadalcanal successfully, as did the American transports. Both forces headed home without interference, and both sides’ troops prepared for the next round. That came near midnight on October 13, when two Japanese battleships pounded the Americans on the island with their 14-inch guns, wrecking the defenses, in a bombardment survivors would never forget.

But while the shellfire did immense damage, the Japanese troops, always hobbled by weak logistics and shortages of equipment, were unable to take advantage of the Americans’ disarray and make the assault that would recapture Henderson Field for good.

Both sides needed reinforcements.

Author David Lippman is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He resides in New Jersey and has written extensively on World War II in the Pacific.

I would have thought Balikpapan was the first US naval victory.