By Kevin M. Hymel

Of all the landmarks in Europe, few are as distinctive and instantly recognizable as the medieval fortress/ monastery of Mont Saint Michel, located on the French coast seven miles southwest of the city of Avranches.

Mont Saint Michel stands out like a beacon visible for miles. The 247-acre rock island in Mont Saint Michel Bay is topped by a towering 11th-century Romanesque abbey, making it one of the most outstanding landmarks in Europe. Below the religious structures lies a town filled with hotels, restaurants, museums, and souvenir shops. An immense wall with defensive positions encircles the entire structure. During high tides, the bay waters surround the island, with only a causeway connecting it to the mainland. Rare, extremely high tides completely cover the causeway.

According to legend, in the year 708, Saint Michael the Archangel appeared to Aubert, Bishop of Avranches, several times and instructed him to build a church on the rocky inlet. Aubert ignored the requests until the angel allegedly touched his head, burning a hole in his skull.

The famous Bayeux Tapestry of 1066 records Harold, Earl of Wessex, rescuing two Norman knights from the Mont’s quicksand. During the Hundred Years’ War, Mont Saint Michel withstood repeated sieges and attacks in the early 1400s. During the French Revolution, the abbey became a prison for political prisoners, but Mont Saint Michel is best known for its cloistered Benedictine monks and the thousands of believers who make pilgrimages to the church each year.

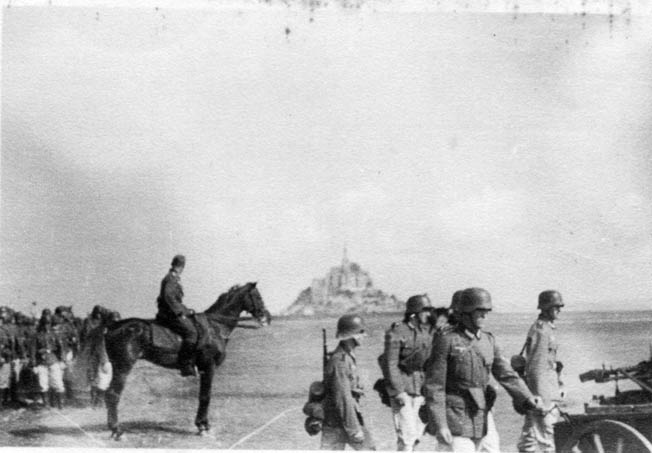

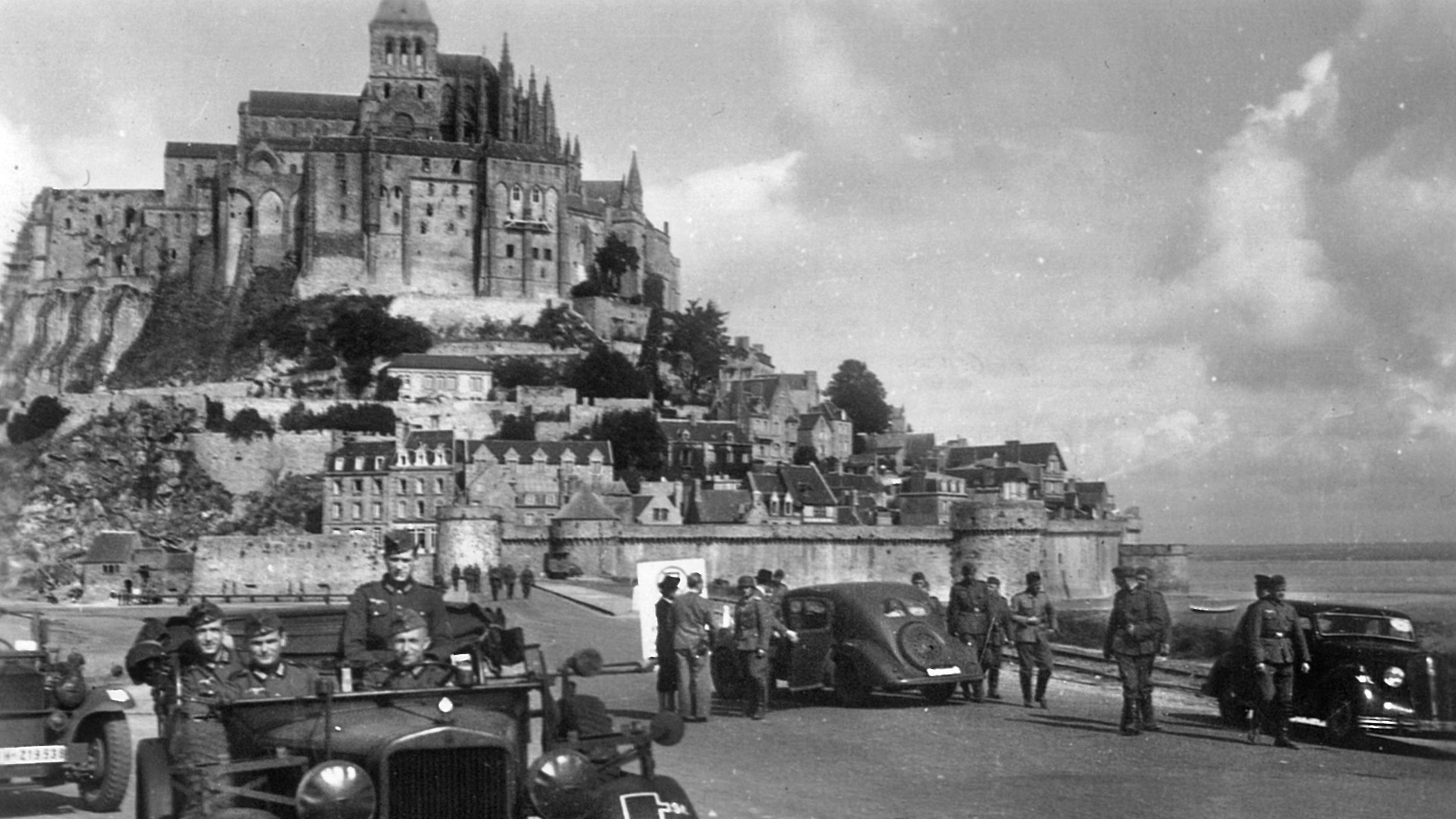

German soldiers had first entered Mont Saint Michel on June 18, 1940, the day before the French government agreed to surrender. The Germans set up a lookout post in the St. Aubert church spire, where bored Luftwaffe observers penned their names (they are still there). Five Luftwaffe servicemen lived permanently in the abbey. Other German soldiers were billeted in the hotels around the Mont and issued official occupation notices. In the summer of 1940, Wehrmacht soldiers held military maneuvers in the shadow of the Mont as they prepared for Operation Sea Lion, the invasion of Great Britain.

To accommodate the occupiers, merchants inside the village had to change their signs from French to German. With 1.6 million French soldiers locked in German POW camps and thousands of others ordered to Germany to work in Nazi industries, wives and daughters became the abbey’s caretakers and tour guides. German soldiers on leave visited the ancient wonder in large numbers, while most Frenchmen, conserving their gasoline, were rarely able to make a pilgrimage. Tourism was further discouraged when the Germans required all French visitors to procure a special pass for their vehicles as well as a hard-to-get permit to gain access to the coastal zone. During the four years of occupation, 325,000 Germans visited the Mont while only 1,000 French made the trek.

The Germans’ presence was obtrusive and unwelcome. When the body of a Luftwaffe corporal washed up in the bay, he was buried in the Mont Saint Michel cemetery. The Germans also banned fishing in the bay as a security measure once anti-invasion obstacles were constructed around the island. Many of these obstacles were simple poles topped with mines and connected to each other by barbed wire. Thousands of these so-called “Rommel’s Asparagus” bloomed in the mud flats around the island.

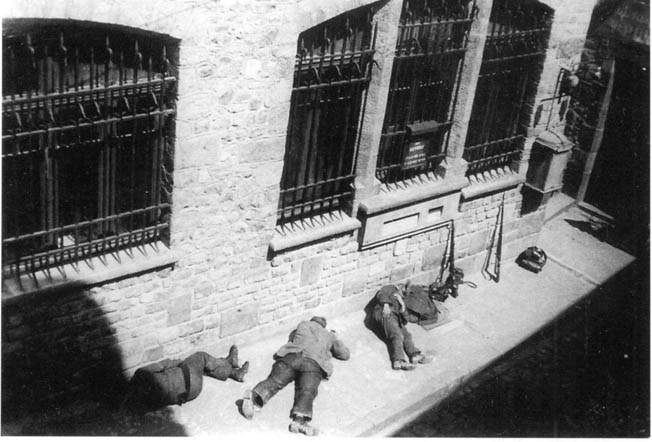

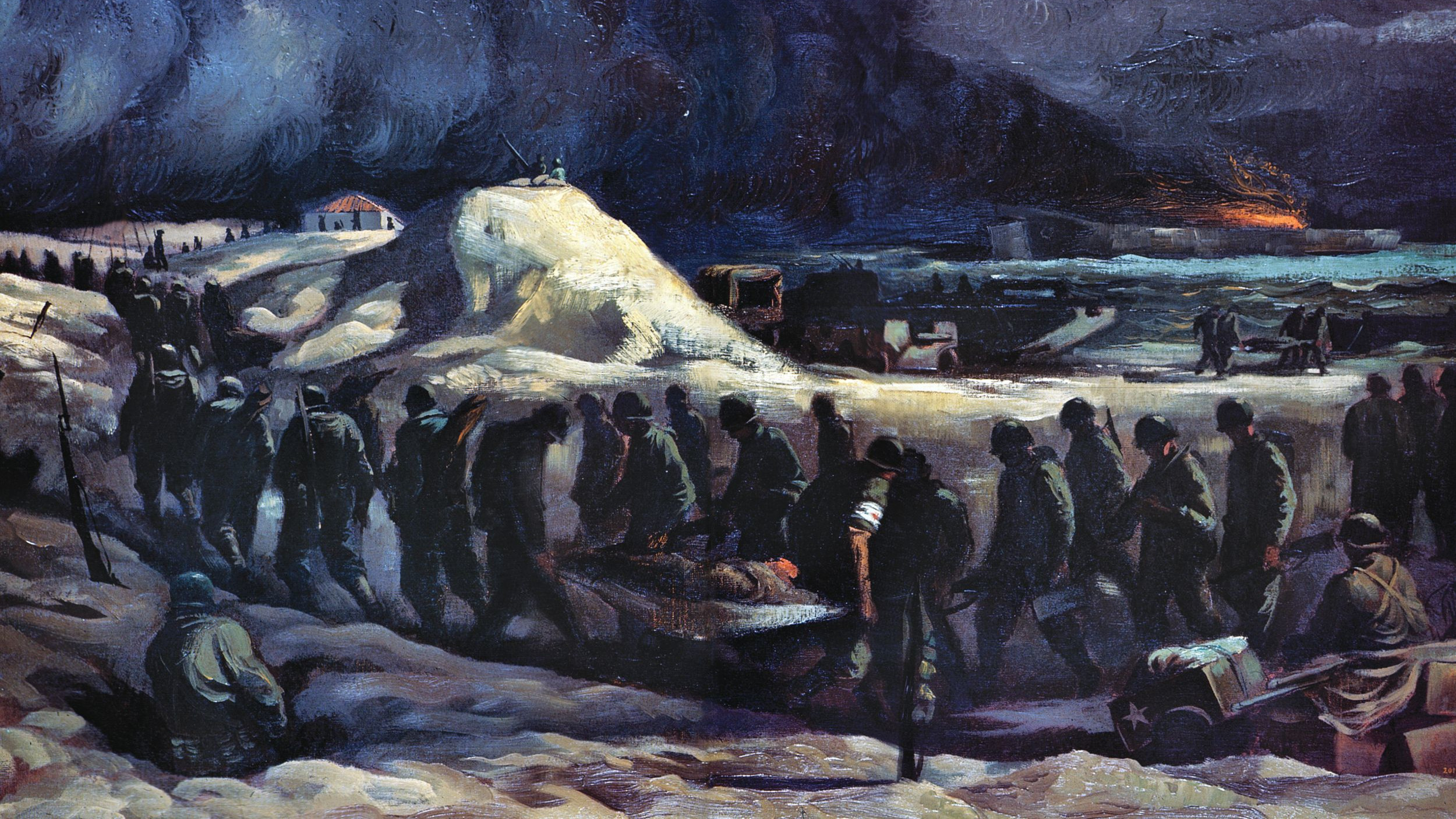

Everything changed on June 6, 1944—D-Day. As the Allies poured ashore and squeezed the Germans into Brittany in early August, the local residents witnessed hundreds of Germans retreating to designated fortress ports, such as St. Malo, Brest, and Lorient. Some of the harried German soldiers showed up at the Mont barefoot. Other exhausted soldiers arrived and collapsed on the cobblestone sidewalks. French residents were terrified the Germans would take out their frustrations on the local population. One brave Frenchman, a Mr. Molleau, ventured to snap a forbidden picture of the defeated enemy on the street below his window. His hands shook as he held the camera, resulting in a blurry photograph.

As the last Germans prepared to depart the abbey, one soldier machine gunned the statue of the founding bishop atop St. Aubert’s church. It was their last menacing act. On July 30, the American 4th Armored Division captured Avranches, effectively cutting off the escape routes south and east. The 6th Armored Division then pushed west toward Pontorson, driving the retreating Germans against the Atlantic coast.

Now the Americans were on the way. On August 1, as the 6th Armored drove west, Private Freeman Brougher of the 72nd Public Service and Psychological Warfare Battalion sped two British reporters, Gault MacGowan of the New York Sun and Paul Holt with the London Daily Express to the Mont. The roads were free of the enemy. Reporter Holt was not surprised by the German’s rapid retreat. He had witnessed the power of American combined arms in action near the town of Gravay. “What the tank commanders do is to pull their tanks off the road, since it is wasteful for tank to fight tank, and then call up the air,” he wrote for the Daily Express. “The Mustangs and Tiffies [Typhoons] are having a rich and rare time with such work.” The result: “The SS paratroopers [sic] walk up the road with their hands on their helmets asking the nearest way to a prisoner cage.”

Whenever Private Brougher pulled over to ask fearful French locals for directions, their attitudes changed when they realized the strangers in the jeep were not Germans. “We saw them go into a hysterical delirium of joy,” Gault MacGowan reported. As the band of liberators neared Mont Saint Michel, they picked up a few hitchhikers. “They sprang from nowhere,” explained MacGowan. “No sooner did the magic words go around, ‘Les Americans,’ than folks came running from every direction.” By the time the jeep rolled to a stop, it had added two priests, three women, a fireman, and several other hangers-on.

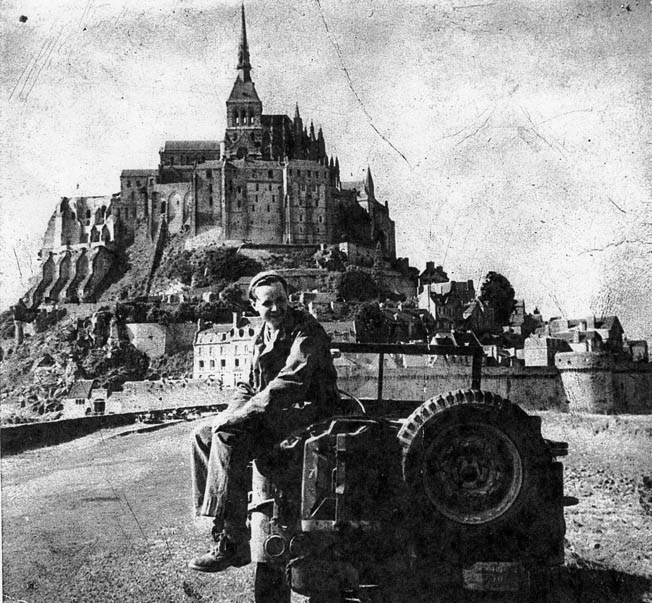

Once across the causeway, Private Brougher drove under Mont Saint Michel’s ancient gates, over the drawbridge, and through the King’s Gate. The crowds pressed in. Everyone wanted to shake hands with their liberators. The Germans surrendered the island abbey without resistance. “I felt like President Roosevelt kissing all the babies,” he told the two reporters. His entrance marked the end of four years and two months of enemy occupation. “I’ve never seen so many people so pleased to see three total strangers,” Brougher said of the liberated French.

MacGowan counted 25 girls kissing Brougher as he accepted six babies for kisses. It’s no surprise the private felt like a politician on the campaign trail. The only people lacking enthusiasm for Brougher’s presence were a handful of German soldiers too exhausted to care. Above the jeep, Mr. Molleau leaned out his window and took another picture, this one much clearer.

The joyous crowd escorted Private Brougher, with the reporters in tow, to the mayor’s parlor above the King’s Gate, where he was toasted with champagne, festooned with flowers, and carried on the crowd’s shoulders through the narrow, cobblestoned streets. He then signed the city’s Golden Book, which recorded a list of local nobility. MacGowan accompanied Brougher to La Mere Poulard Hotel, where the reporter signed the visitor’s book, penning a little hyperbole, “first American correspondent in Mt. St. Michel and the first of anybody with the liberation.”

MacGowan credited Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, the First Army commander, for making the liberation possible. “Private Brougher might never have reached this important natural curiosity and ancient monument of France had not an armored spearhead of General Bradley’s hard driving Army been occupying the attention of the Germans when [Freeman] left the mainland for Mont St. Michel.”

MacGowan was correct. Omar Bradley was indeed responsible for the armored thrust, but he had some assistance from Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., who had taken nominal command of Bradley’s VIII Corps a few days earlier and directed the 6th Armored Division’s drive into Brittany.

Patton had a connection with Mont Saint Michel. As a young lieutenant he visited it with his wife while studying swordsmanship at the French cavalry school in Samur. Private Brougher liberated it on the same day that Patton’s Third Army became operational. Although busy with pushing his army west, south, and east, Patton took the time to note in his diary, “The 6th Armored Division is at Pontorson, where Beatrice and I spent the night in 1913.” He obviously did not know yet that the abbey island had also been liberated.

All the Frenchmen in the Mont had the same question for their liberators: How could they join the French Resistance? The women wanted to know what to do with collaborators. The priests wanted to know when the French Army would arrive to keep order.

The collaborators were dealt with first. Male collaborators were put under lock and key; the abbey would serve as a prison for the first time since the French Revolution. The women collaborators had it worse. The town’s women tore the collaborators’ blouses off their backs and beat them with canes and sticks. The bruised and bleeding women fled for the safety of the ramparts while Private Brougher and the reporters begged the mayor to issue a proclamation calling for calm until authorities arrived. “The collaborators now definitely live on the wrong side of the railroad tracks forever,” reported MacGowan.

Soon, M-8 armored scout cars arrived, and the soldiers dismounted to tour the newly liberated ancient wonder. Before Freeman left, he put two German prisoners on the hood of his jeep and drove them to a POW camp.

MacGowan filed a story that day that appeared in the New York Sun, titled “Mont St. Michel Hails Its Liberator.” He referred to Brougher in the subtitle as “A G.I. Chauffeur for Sun Reporter.” Holt may have submitted a story to the London Daily Express, but no article appeared. The Express’s editors may have felt the story not important enough to appear in its pages, or possibly that it was too “American” for its British readers. His next story, about the siege of St. Malo—20 miles west of Mont Saint Michel—did not appear until the August 8 issue.

While the American forces drove the Germans farther west, the Mont was still not immune from the war. A few days after its liberation a German plane crashed in flames some 200 meters from St. Aubert chapel, almost hitting the abbey. It was the last act of war for the Mont. It soon became a tourist attraction again, this time for the Americans. When the war ended, the locals removed the body of the Luftwaffe corporal from the cemetery and returned it to Germany.

As for Private Brougher, liberating Mont Saint Michel was the highlight of his military service. He told his daughter Janet that the people called him “the savior of Mont Saint Michel.” After the war he returned home to Pennsylvania, where he became a high school business manager. He returned to Mont Saint Michel with his family in June 1987. Unfortunately, the mayor was away, so Brougher could not see the Golden Book he had signed 43 years earlier. Instead, he gave his wife, Frieda, and his children, Janet and James, a tour of the abbey he liberated.

“He showed us everything that he had seen,” recalled Janet. Freeman Brougher would remain proud of his accomplishment until his death in 2003.

This was a great article ! I had no idea . Thank You !

Loved the story: reminded me of my visit to the Mont the same year that Mr.Brougher made his family visit, 1987. My wife and I, both Canadians, visited Bastogne as well.

Very interesting. It truly is a magical place.

Good article

Ma reconnaissance aux troupes américaines pour le courage et le dévouement pour la libération de le La France. Le site est enchanteur et la renommée est internationale.Je me rappelle aussi des moutons aux pieds noirs lors de ma visite de la grève.

Souvenir encore présent .

My wife and I stayed overnight there in 1995 and enjoyed an omelet at L Mere Poulard. The hotel on the island had pictures of WW11 American soldiers at the time of liberation. One of the pictures was of my boss , now a general, when I was stationed in Germany in the 70s.

We visited Mont Saint Michel in 2009 as part of a remembrance ceremony for my father-in-law Bill Tucker, who parachuted into Ste. Mere Eglise with the 82nd Airborne and helped liberate the town. Bill eventually became an honorary citizen of Ste. Mere Eglise and helped create the 82nd Airborne Museum in Ste. Mere. My fondest memory of our trip to Mont Saint Michel was the “battle of the bands” of French, German and U.S. marching bands. After a few go-rounds, the U.S. military band struck up “Stars and Stripes Forever!” It still gives me goose bumps when I remember the horn section standing for the big finale! A truly memorable moment in a pilgrimage to inter Bill’s ashes, as he had wished, where his comrades had died liberating northern France.

I am doing a report for school about The Mont Saint Michel and I think that your story is fascinating and I would like to use your story as part of my project. I think that it would be a great part of history. I want to thank your father in law Bill Tucker for serving in the armed forces and you for putting his soty out for others to hear this great part of history. So I am asking you If I can put your story on my presentation I will have your name and anything else that you want me to put for the credits.

— Thanks Brayden

What a wonderful story ! I enjoyed this article while researching for my historical fiction sequel. Some of my novel Time, Heal my Heart is set at MontSaint Michel and so I am excited about a continuation of the story this time during WW2 . All names will be changed and story is fiction.

Great story! Thanks!