By Kevin M. Hymel

Major General George S. Patton, Jr. had no patience for soldiers disobeying the rules of combat at his Desert Training Center in Southern California. During one maneuver, he spotted Lieutenant James Craig riding in a scout car with its side armor folded down. “Looootenant!” he bellowed out in his high-pitched voice, “Get that damn side armor up!”

Craig was not about to disobey the order. “So, of course, we closed that up,” Craig recalled. It was the summer of 1942, and the U.S. Army was preparing to fight the Germans and Italians in North Africa.

Kentucky, commanded General Patton’s headquarters tanks in North Africa and Sicily.

Patton’s anger quickly subsided. Soon after, he put the “Looootenant” in command of 15 M5 Stuart light tanks to protect his I Armored Corps headquarters. “I didn’t think he knew my name,” said Craig. The tanks Craig would command each held a crew of five and sported a 37mm main gun and three .30-caliber machine guns. Craig named his new unit the Provisional Tank Company.

Two of the tanks were customized for the general. Both had their double-turret hatches replaced with a single large one to allow Patton easier access. “Their 37mm cannons were [also] replaced with similar looking wooden replicas,” said Craig, “and the breeches were also removed.” The accommodations would also give Patton more movement inside. Two metal flags were attached on the front of whichever tank he used: one with his two-star rank and the other with the I Armored Corps emblem. Whenever he was not using either tank, the flags were stored inside.

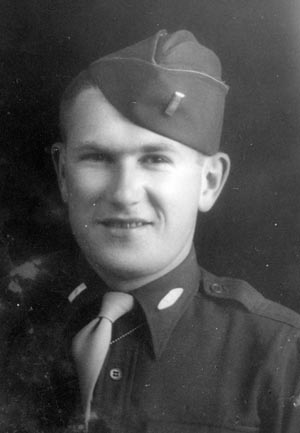

Lieutenant James Craig was one of Patton’s better trained soldiers. A native of Shelbyville, Kentucky, he had been training with the U.S. military since he was 16, when he attended the Citizens’ Military Training Corps (CMTC) at nearby Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, in 1937. The CMTC was a summer training program that did not require enlistment. Although too young when he applied, Craig received a waiver and spent the next three summers learning how to be a soldier.

With training under his belt, Craig joined the Army at Fort Knox. His company commander made him a clerk, which he did not like. “I wanted to be in the tanks,” he recalled. He got his tank when he transferred to Fort Bliss, Texas, as a tank driver, and went from private to staff sergeant in a few months. When the camp colonel saw him training a tank company, he told him, “I don’t have any lieutenants who can train as well as you do. I’m going to send you to OCS [Officer Candidate School].”

Craig returned to Fort Knox and trained for three months to be an officer—one of the so-called “90-day wonders.” On one of his leaves, his cousin took him to Owensboro and introduced him to a young girl named Geraldine Hayden. “She was 14 and she told me she was 16,” said Craig. They spent a date sitting on a pier with their feet in the water. He saw her a few more times, and the two began writing letters.

Craig was visiting his parents when he heard over the radio that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. An announcement followed: “All military personnel report back to your duty stations.” A month after Pearl Harbor, he graduated from OCS on January 22, 1942. When Lt. Col. Stovall, the OCS commander, pinned on Craig’s gold second lieutenant bars, he told him, “I got you an assignment at Fort Benning, Georgia, with General Patton, with the I Armored Corps.” Stovall had been Craig’s company commander at Fort Knox and was looking out for him.

Craig arrived at Benning, where he became the corps’ Headquarters Company motor officer, responsible for two scout cars, two 21/2-ton trucks, and two command cars. He met General Patton briefly but did not speak to him. He also met Captain Richard “Dick” Jensen, Patton’s aide-de-camp and an avid motorcycle rider. Jensen often checked a motorcycle out of the motor pool and eventually talked Craig into riding with him. Craig had never ridden before, but Jensen showed him how. They spent their evenings riding all over the fort.

The joy riding did not last long. Patton was placed in command of the yet-to-be-established Desert Training Center, so Craig loaded his vehicles onto a train and headed west. The center, Craig recalled, “was not much to look at.” A circus-sized tent housed the officers’ recreation hall, which included a bar where officers gathered to listen to Patton tell stories about World War I. “He was very genial and nice when he talked to us that way,” recalled Craig.

Along with Patton were his chief of staff, Colonel Hobart “Hap” Gay, and one of Patton’s operations officers, Colonel Hugh Gaffey. When Craig wasn’t meeting new officers or training his men, he wrote to Geraldine. He even mailed her a promise ring, though he never spoke about marriage in his letters.

Soon after, Craig was given command of the tank company and ordered east. He loaded his tanks on a train and headed for Fort A.P. Hill in Virginia. Once there, he and his men waterproofed the tanks, including attaching large vents over the exhaust and intake pipes. Once the task was complete, the train headed to Norfolk, where the USS Ancon, an ocean liner now serving as a troop ship, waited at the pier.

The next morning, the ship’s crew loaded the tanks into one of the holds. Craig slept in a stateroom with nine other officers in three triple-decker bunks. “I had the top bunk,” he recalled. Most of the troops aboard were members of the 3rd Infantry Division. Once the ship set sail on October 24, the men learned they were heading for North Africa, which surprised Craig. “What the hell are we doing in Africa?” he asked his fellow soldiers. “The war’s in Europe.”

Craig was now part of Patton’s Western Task Force for Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa. Patton’s mission was to capture Morocco, the only Atlantic-facing objective; the Eastern and Central Task Forces would assault Oran and Algiers on the Mediterranean coast.

Patton’s force would assault three areas: Port Lyautey in the north, Fadala Beach near Casablanca in the center, and the port of Safi in the south. They would not be fighting the Germans, but the Vichy French, who had sworn allegiance to Nazi Germany after their defeat in 1940. Craig would be landing at Fadala Beach.

Every day, Craig went into the Ancon’s hold to check his tanks. During a storm, he noticed one of the tanks had broken loose from its cables and was sliding into another tank, then smashing into a stack of 105mm artillery shell crates. Shells rolled all over the deck. Craig ran up to the bridge and reported to the officer of the deck. “We’ll take care of it,” he said. But then Craig asked, “What about the 105 ammunition that’s rolling around on the deck that’s broken lose?” Everyone jumped into action. “They started screaming over the public address system,” recalled Craig. “They had people running down there and tied it down.”

On another day, Craig was again below deck inspecting his tanks when he felt the ship shudder. “What the heck is going on?” he asked himself and ran topside to see a destroyer dropping depth charges and foam rising to the surface. “I could feel the vibration,” he said. He was curious but not scared. “We hadn’t learned to be scared yet.”

On November 8, Craig awoke before sunrise to the sounds of firing on Fadala Beach. To ward off the cold, he donned a wool uniform and a tanker’s jacket. He armed himself with a Thompson submachine gun and a backpack filled with .45-caliber ammunition stick magazines. Reaching the top deck just as the sun cracked the horizon, he could see the 3rd Infantry troops in landing craft going ashore and hear the battle taking place on the beach. Knowing his tanks would be going in with the third wave, he was preparing to get his men into their tanks when he received a new order: Only one man would ride in each tank for the assault. The rest would go in on foot.

Instead of clambering into a tank, Craig climbed down a cargo net to a Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP) bobbing in five-foot swells. Someone called out, “Step back!” and he jumped back just as the LCVP dropped. Craig’s boots landed in the craft, but he fell back. Before he fell over the side, other soldiers grabbed him and pulled him in. The LCVP headed ashore but soon hit a sandbar. The front ramp dropped and everyone piled off. “The water was up to our necks,” recalled Craig, whose backpack weighed him down as he waded through the cold water. “I was soaking wet with a chill.”

As he reached the beach, an artillery round exploded about 40 yards away. “What the hell was that?” he asked the men around him. Soon, a French fighter plane dropped out of the sky and strafed the beach. Craig ducked. The drydocked French battleship Jean Bart fired more shells at the beach.

Directly in front of Craig stood the Miramar Hotel. He and several infantrymen entered and searched room by room for any hidden Vichy French. All they found were a few German uniforms hanging in closets, possibly belonging to the 10 members of a German armistice commission who had been captured in their pajamas.

In the basement, they discovered an unexploded shell fired from the Jean Bart. It had smashed between two windows and taken out a wall. “We could see the shell lying on the ground in the debris,” said Craig. That night Patton made the hotel his headquarters.

While Craig awaited his tanks, he found a chair and sat down. A Moroccan approached him holding a bottle, and Craig gave him a dollar for it. He took a swig. “It was the hottest stuff I ever tasted,” he recalled. “It must have been 100 percent alcohol.” He offered it to his fellow soldiers, but they could only tolerate a sip. He threw it away.

Three hours later, Craig finally got his tanks. They were lowered into landing craft by the Ancon’s cranes for the trip ashore. After they roared up the beach, the men worked to remove the exhaust vents they had attached back in Virginia, but they wouldn’t budge. “Someone had spot-welded them on,” he said. Craig saw a nearby bulldozer and asked its driver to place his blade at the base of each vent and lift. One by one the driver tore off each vent. “None of them would come loose on their own,” he explained.

Someone on the beach called out, “Look! There’s a submarine!” Craig watched as a submarine surfaced and sank two ships. It was too close to the American ships for them to depress their guns. “He sat there and fired two torpedoes,” Craig recalled. “I heard he got several other ships.” While there is no record of submarines sinking American ships on November 8, a surfaced submarine was recorded sinking vessels three days later.

On November 11, Craig’s unit received orders to move to Casablanca. Patton’s forces had surrounded the capital and were preparing to attack when the Vichy French surrendered. A delegation later arrived at the Miramar Hotel and officially surrendered to Patton. Craig’s tanks rolled into the city. “When we went in, there was nothing,” he said. “The 3rd Infantry had already gone in. Nobody shot at us or anything.”

Some people cheered Craig’s tanks, while others cursed. “I didn’t understand French,” he explained, and could not understand the foreign remarks hurled at him. The tanks encamped at the city’s central park, which would be Craig’s home for the next four months.

The surrender ended the war in Morocco. “We sat around a lot,” recalled Craig. He dined on C-rations for both Thanksgiving and Christmas and came to hate the canned cheese that came with the K-ration. One day he nabbed some sugar and cans of jam at the city’s port. As he returned to the park with his booty, he came across a Frenchman selling pigs. Craig traded his goods for the pig, and later he and his men enjoyed a barbeque.

The Germans constantly reminded the Americans there was still a war on. On New Year’s Eve 1942, the Luftwaffe raided Casablanca. Searchlights swept the skies as anti-aircraft crews fired wildly into the night. When a bomber flew over the park and dropped a bomb, Craig opened fire with a scout car-mounted .50-caliber machine gun. The bomb crashed into the park but did not explode. Then Craig noticed a light in the window of a nearby building, and he and his men fired at it until it went out. “We figured someone was making a signal,” he said.

The next day Craig and his men found the unexploded bomb full of bullet holes and called for an ordnance bomb disposal crew; they told him that his bullets had disarmed it. Any relief he may have felt quickly ended when a superior officer chewed him out for firing into the building. “I got hell for that,” he said.

Two weeks later, on January 14, 1943, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt came to Casablanca to meet with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill for a 10-day conference to determine the direction of the war. For extra security, soldiers set up a machine-gun nest atop Patton’s Anfa District residence. Whenever Craig served as Officer of the Day in the building, he passed Patton’s parlor on the way to the machine gun. One time he spotted Patton there, but the general was too busy to look up. Another time, an old man waved to him. Craig realized it was President Roosevelt, but he did not stop. When he returned, the parlor door was shut.

In late February, word reached the men that the Germans under General Erwin Rommel had launched an attack through the Kasserine Pass in Tunisia, smashing Maj. Gen. Lloyd Fredendall’s II Corps. When it was over, Fredendall had lost 4,300 men killed and wounded to Rommel’s 201, yet little official news came from the battlefront. “We didn’t know much,” said Craig. “We were told that Fredendall had been relieved of his command because of Kasserine Pass.” To replace Fredendall, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the commander of all troops in North Africa, selected Patton.

Patton flew out of Casablanca on March 5 and took command of II Corps. The next day he sent for his vehicles. Craig would lead a convoy consisting of two scout cars, a jeep, and a deuce-and-a-half truck filled with gasoline to Patton’s new headquarters, more than 1,500 miles away. “We were given a time and date to cross the IP [initial point],” said Craig. Mechanics worked on the vehicles through the night to prepare them for the long journey.

The next morning, Craig crossed the IP on time but only drove about 100 yards before one of the scout cars tore a brake line. “We could see the fluid on the ground,” he recalled. Craig had gone back to get a mechanic when he bumped into Hap Gay, now a brigadier general. An angry Gay held Craig personally responsible for not preparing his vehicle properly. Craig later found out that Gay had written a special efficiency report on him. “It was a terrible report,” Craig said. “I didn’t know what a brake line was at that time.”

Once the vehicle was repaired, the convoy took off again and made it to Gafsa, which had been captured by the 1st Infantry Division on March 17. There Craig was greeted by Captain Jensen, whose sergeant took charge of Craig’s soldiers while Jensen took him to a mess tent. They sat in a corner eating next to an open window flap. Someone walked by and asked, “Craig, what the hell are you doing here?” It was Brig. Gen. Hugh Gaffey, now Patton’s II Corps chief of staff. Craig told Gaffey he had brought Patton’s vehicles. “Good,” said Gaffey. “I need an aide and you’re it.”

That night, Jensen brought Craig to Patton’s residence to celebrate the general’s promotion to lieutenant general. The men sat around a long line of fold-out tables with Patton at the center and dined on rations. Craig sat at the foot of the table, trying to keep his eyes off Patton. “He was smiling and had his third star on,” recalled Craig, “I was afraid to look at him.”

For the next two months Craig served under Gaffey, often riding with his new boss to division and regimental headquarters. “He loved to ride around in a jeep,” recalled Craig, who manned the .50-caliber machine gun mounted in the back. On long rides, Craig would stare at the countryside until Gaffey looked back. “Craig, dammit!” he would shout. “The planes aren’t out there,” pointing at the horizon. “They’re up there!” pointing up.

Craig accompanied Gaffey to Kasserine Pass, while Graves Registration troops cleared out the dead. Examining where the bodies lay, Craig concluded that the Americans had retreated into the pass before they were killed. “There were a whole bunch of bodies,” he said. “I didn’t look at them closely.”

Craig proved he could deal with enemy planes. One day he was riding down a road in Gaffey’s jeep between two marching columns of infantry when two German fighter planes roared straight up the road. As enemy fire stitched the ground, Gaffey’s driver hit the brakes, and he and Gaffey bailed out. Everyone ducked for cover except Craig, who returned fire. “I was firing point blank at this thing coming right at me,” he recalled. He could see the German tracers zipping at him and his own tracers hitting the plane. Suddenly, the first plane pulled up and crashed into a hillside.

The second fighter plane then closed in. “I started firing again, and before he got to us, he started smoking.” The plane peeled off and, with smoke pouring out, flew over a hill and disappeared. The troops cheered Craig’s marksmanship, and he heard a colonel tell Gaffey, “He shot down two planes, we oughta give him a medal.” But Gaffey was unmoved. “He’s just doing his job,” he told the officer. No medals were forthcoming.

Craig was doing his job again when he and a driver headed to the front to deliver a message to a combat unit. They made a wrong turn and passed a lone trooper walking the other way. “I looked at him, and he looked at us, and we kept going,” said Craig. When they topped a hill overlooking a creek bed with high banks and woods on the other side, Craig told the driver, “Let’s park on top of this hill.” Armed only with a .45-caliber pistol, Craig got out and dropped into the creek bed. As he was about to climb over the far bank he heard German voices. “I sneaked a peak and I saw coming out of the woods five or six Germans.”

He ducked behind a bush and froze. The Germans sat down on either side of the bush and ate their lunch. “I could hear them talking.” He thought of killing them with his pistol, but he knew he only had seven rounds, and the Germans were too spread out. When they finally left, Craig climbed back up the hill to find his ride gone. He walked back until he came to the trooper he had passed earlier. “Who the hell are you?” Craig asked. “I am the point,” the man told him. Incredulous, Craig asked, “Why didn’t you stop us?” The man responded, “You’re an officer, you’re supposed to know what you’re doing!”

Craig continued down the road until he spotted his vehicle and driver. Soldiers surrounded the driver as he explained Craig’s disappearance. When Craig asked what had happened, the driver told him, “I saw those Germans come out of the woods, and I thought you had had it. I got out of there.”

Serving with Gaffey, Craig got to see many important American leaders, including Maj. Gen. Terry Allen, the commander of the 1st Infantry Division, as well as Brig. Gen. Teddy Roosevelt, Jr., the son of the 26th president of the United States and cousin of the current president, but Craig never spoke with them. He also met Lieutenant Al Stiller, another member of Patton’s staff whom Craig considered “very back-woodsy.”

One day, Craig visited corps headquarters and spied the situation map. As he looked at it, Maj. Gen. Omar Bradley, Patton’s deputy commander, entered the room. He was not angry with the curious lieutenant and instead explained the different markings on the map. “He was very friendly,” said Craig. “I liked him very much.”

And then there was Patton, whom Craig considered a sharp disciplinarian who took seriously the rules of war. Soldiers failing to buckle their helmet’s chinstrap was one of his pet peeves. “He was mad about those chinstraps not being on,” said Craig. “He would get you if you didn’t. He would chew you out.”

One day Craig watched four American soldiers march some German prisoners past Patton. Local Arabs rushed the Germans and began stealing their personal items. Patton stormed the Arabs. He kicked one in the rear and chased away the others. “These are prisoners of war!” he yelled at the Americans. “They are military people! They’re honorable people! Don’t let them pick on them like that!”

On March 26, General Eisenhower came to congratulate Patton for successfully defending El Guettar from a German attack three day earlier. That night Craig bedded down in a room with all the other generals’ aides, each man on the floor in a sleeping bag. He was sleeping close to the door with his arm stretched out in the dark when somebody stepped on his finger.

Craig shouted, “Who is stepping on my…!” when he looked up to see General Eisenhower. “Sorry sir,” he quickly apologized. “I’m sorry,” said Eisenhower. “I’m looking for my aide.” Craig reached over and gave Eisenhower’s aide a yank. “He was sound asleep,” Craig recalled.

Later, Patton and Eisenhower toured the front, walking by Craig’s slit trench. “They didn’t notice me,” he remembered. But he did hear Patton tell Eisenhower, “I’m gonna drive right to the sea and we’ll separate Rommel’s forces, then we can mop him up between us and [British General Bernard Law] Montgomery.” Eisenhower was having no part of it. “You move one step from this spot, and I’ll relieve you.” Eisenhower wanted Patton to keep pressure off Montgomery’s front, not race to the coast. The two generals walked away. “I think Patton was dumbfounded,” said Craig.

Craig was at the front when Captain Jensen was killed on April 1. Although Patton and Bradley both recorded that Jensen was killed during a Luftwaffe raid, Craig recalled that enemy artillery killed his friend. “He was in a slit trench, and I was about four or five feet from him in a slit trench,” he said. They could hear a radio operator talking inside a nearby half-track. A shell arced over, and Craig heard the operator say, “We’re being shelled. That one just went over us.” Jensen called over to Craig: “That guy’s telling the Germans where the artillery’s going!” Craig replied, “I’ll shut him up!” He ran over to the operator and told him to be quiet, explaining that the Germans were monitoring his communications.

Just then a shell exploded right next to Jensen’s slit trench, killing him. Craig watched as Jensen’s body was put on a stretcher, but he could not stay long. Gaffey arrived and picked him up. “He was going somewhere, and I had to go with him,” he said. Craig later served as a pallbearer at Jensen’s funeral. “Jensen was the best friend I had,” said Craig. “He was always helping me out.” Craig looked back fondly on his motorcycle rides and their lunch together in Gafsa. “He was always saying ‘hi’ to me and going out of his way to speak to me.”

Three days later, on April 3, three Allied air generals visited Patton. British Chief Air Marshal Arthur Tedder and Americans Lt. Gen. Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, commander of the Twelfth Air Force, and Maj. Gen. Laurence Kuter, deputy commander of the North African Tactical Air Force, were talking with Patton when Craig happened by the window and heard one of the generals telling Patton not to worry about air superiority, “We have it.”

Just then, four German fighter planes flew down the street, bombing and strafing. “This German plane came over and dropped a bomb a little more than a block away from us,” recalled Craig. “There was a terrific roar.”

When it was over, Spaatz asked Patton, “Now how in the hell did you manage to stage that?” Patton cleverly answered, “I’ll be damned if I know, but if I could find the sonsabitches who flew those planes, I’d mail them each a medal!” The airmen hurried out of the headquarters, yelling back to Patton, “We’ll get some support for you right away!” Amused, Craig then heard Patton say, “I would have paid that pilot to drop that bomb closer to this building.”

When Axis forces surrendered in Tunisia on May 13, 1943, Gaffey told Craig he would be taking over the 2nd Armored Division and asked if he wanted to come with him. Craig told him, “No sir, I want to go back to my tank company.” To which Gaffey said, “So be it.” A tank commander again, Craig flew back to Casablanca, where he loaded his 15 tanks, a truck, and a jeep onto a train—one tank per rail car—and brought them to Bizerte on Tunisia’s northern coast.

Upon arrival, Craig told a French railroad yardmaster that he needed help getting to the loading docks to unload the tanks. The Frenchman said it would not be possible for a few days. One of Craig’s noncommissioned officers suggested unhooking the cars and driving the tanks off the back, figuring that the weight of the tank would tilt the car down, allowing the tank to roll off. “Let’s try it,” said Craig.

The first tank rolled slowly off its car, causing the front to rise. As the tank rolled off, the front end banged down on railroad ties, missing the rails. As they prepared to release the next tank, the yardmaster ran out shouting, “You can’t do that! You can’t do that!” Craig told him he had to unload the tanks today. “I can do it my way or we can do it your way.” The panicked Frenchmen told him, “I’ll get a locomotive!” The tanks were all offloaded.

Craig led his tanks to a hilltop outside of Bizerte. One morning he and his men were shaving out of their helmets under some olive trees when a German airplane flew over and antiaircraft guns opened up. A new officer, a Lieutenant Anderson, looked up as he held his helmet and said, “You know, all that comes up is bound to go down.”

Just then a dime-sized piece of metal tore through the tree leaves and gouged the top of Anderson’s head. “We could hear it come down,” said Craig. “It cut a nice gash in him.” Anderson dropped to his knees as everyone slapped on their helmets. “I took him down to the aid station, and they evacuated him.”

Soon Craig’s unit began training for an amphibious landing, loading their tanks onto landing craft and practicing beach assaults. Once their training was complete, they loaded onto a Landing Ship Tank (LST) and set sail. While at sea they were told two things: that they would be invading Sicily and that they were now part of Patton’s Seventh Army, which had been approved after setting sail. “We expected we were going up to Europe,” said Craig. They were going to Europe, just not the part he was thinking of.

Patton’s new Seventh Army assaulted Sicily’s southern shore on July 9. Airborne forces were dropped in first, followed by an amphibious assault. By the time Craig’s LST landed on Gela Beach, the fighting had already moved inland, although enemy artillery occasionally exploded on the beach. “It came close enough to see, but it didn’t hit any of us,” he recalled.

The fighting around Gela was initially intense, but once Patton’s army cracked the German and Italian lines, the Americans advanced quickly up the center of the island bound for Palermo on the north coast. Palermo contained a large harbor, where Patton could stage future operations. Patton’s troops captured the city on July 22.

Craig’s tanks entered Palermo at night. Not knowing where to go, he stopped his convoy at a large intersection outside the city. Suddenly, a rifle shot cracked the silence. A sniper was taking shots at him and his men. “We could see the flash of fire and see fellows go by us,” recalled Craig. “I just turned one of the 37mm guns and fired a shot at the sniper.” The sniping ended. An American soldier appeared and led Craig’s company to a camp area.

With Palermo now in his possession, Patton turned east to pursue the enemy to Messina at the northeast corner of the island. He wanted to capture the city, not only defeating the enemy but beating Montgomery, proving American troops were as good as, if not better than, the British.

But the Germans and Italians blunted Patton’s advance, fighting his troops to a stalemate. To break it, Patton launched three amphibious assaults to get behind the enemy, the first at Sant’ Agata, the second at Brolo, and the third at Falcone, some 20 miles west of Messina. The first two assaults came close to routing the enemy, and Patton hoped the last one would succeed. Both Bradley and Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott, the 3rd Infantry Division commander, begged him to cancel the landing, arguing that Truscott’s troops had already passed the port town. Patton insisted it go forward.

Patton picked five of Craig’s tanks for the Falcone attack. Craig loaded them onto five Landing Craft Tanks (LCTs) and headed out to sea. When the craft turned south for the run onto the beach, Craig noticed an American tank destroyer atop a hill. Worried that it would open fire on him, he radioed his tank crews, “Turn your turrets so they can see the star on the side!” Everyone turned their turrets. “They didn’t fire at us,” he said. Craig’s tanks rolled off the landing craft and headed east but did not reach Messina. Truscott’s troops had already captured the city, hours before the British.

With the campaign over, Craig welcomed a new commander, Captain Turner Max Smith from Spartanburg, South Carolina, who had previously commanded an airfield security force that had been disbanded. “Since he was an armored officer, Patton put him over me,” he said. Craig also started hearing rumors that Patton had slapped two soldiers in different hospitals during the drive to Messina, but he did not believe them. He could not believe Patton was capable of such behavior. “Of course, I was wrong,” said Craig. “He did it.”

The Provisional Tank Company headed back to Patton’s headquarters in Palermo. On the way, they passed tanks and troops heading east. They also passed a local Sicilian riding a horse pulling a cart with extended axles. One of the axles struck a tank’s tread, and the cart and its horse flipped up in the air then smashed to the ground, killing the horse. Craig’s tankers had to wait for the mess to be removed before they could go forward.

That night, Craig and Smith visited a restaurant they had passed earlier. When they read that steak was the special on the menu, Craig asked Smith, “Smitty, isn’t this where we killed that horse today?” Smith agreed. The waiter came out and said, “Steak.” Smith asked, “Horse?” and the waiter said, “Si, steak, steak.” The two men looked at each other. “We got spaghetti,” said Craig.

Craig spent most of the trip back locating and defusing mines and putting them in his jeep’s trailer. Once in Palermo, he and Smith were watching a German air raid from an archway over a road when Smith asked, “By the way, Jim, where’s that trailer of yours?” When Craig said it was beneath them, Smith immediately shouted, “Get it the hell out of here!”

The company camped on a horse racing track near the harbor, and the officers occupied a jockey weigh station, a one-room cottage with no windows. One night German planes raided the harbor and hit an ammunition ship. “We could hear it going off, but then it went quiet,” said Craig. He went to the door and looked out when something nearby exploded. “I turned around and ran over two officers.”

Things quieted down again, and Craig looked out the doorway when a second explosion occurred. When he got up a third time, Smith said, “Jim, you just sit down. We’ll go look.”

Craig often reported to General Patton’s office with the color guard to retrieve the Army flags for ceremonies. He always addressed Patton the same: “Sir, I’ve come to take the colors.” Patton would get up from his desk and stand to one side to watch. Craig would take colors, one at a time, and put them in the color guards’ hands, then they would march, single file, out of the room. “He would stand there and watch the whole thing,” said Craig. Patton did the same thing when they returned the flags.

On Armistice Day (today’s Veterans Day), November 11, 1943, which was also Patton’s birthday, the general dedicated a cemetery for the dead of the 2nd Armored Division. Craig led the color guard, marching them out to the cemetery and delivering a 21-gun salute. It was one of his last actions in Sicily.

Soon after the ceremony, Craig stepped in a hole and tore his knee ligaments. Barely able to walk, he reported to an aid station where he was loaded onto a hospital ship headed to Tunisia. From there it would go to England and the United States. The ship stopped in England to pick up an important cargo: American Army nurses and Women’s Army Corps members, all of whom were pregnant. Since the Army prohibited pregnant personnel, the women were being returned stateside to be discharged.

The ship continued west, and by the summer of 1944 docked in Boston, Massachusetts, but the men were not allowed to debark. An announcement went out that all troops would remain below decks until the female passengers were offloaded. As the women walked down the gangplank, the band on the dock struck up the song, “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You, Baby.” The men below decks went wild. “You should have heard the roar on that ship,” said Craig.

Craig was transferred to the 3rd General Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, where, after two weeks of convalescing, he could walk with a cane. He went on leave to visit his parents, who now lived at Fort Knox. Soon after, he traveled to Owensboro to see Geraldine. He found her at a party, and when she spotted him she ran over and grabbed him.

“She was so happy. I was happy,” recalled Craig. They enjoyed being together again and were married on February 13, 1945. They eventually had five children: Judith Ann in 1946, Rick in 1947, Michael in 1949, Marie in 1954, and Penny in 1956.

Craig remained in the Army and went to Korea in charge of a Sherman tank company with the 1st Cavalry Division in the Pusan Perimeter. The North Korean Army had invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, and had driven South Korean and American forces into the tight perimeter. Craig led his company across the Naktong River and parked on a ridge, where they came under enemy artillery fire. He was climbing onto his tank when he slipped and hurt his good knee. “It hurt like hell,” he recalled. Again, unable to walk, he was put on an airplane to Japan to recover. He missed the rest of the war.

After 20 years in the Army, Craig retired from the service in 1960 and eventually worked for the Air Force Defense Supply Agency until his final retirement in 1983. As of 2017, he lives in Richmond, Virginia, with most of his children living close by.

Craig looked back fondly on his World War II service. Reflecting on his old boss, he praised Patton as a military commander: “I thought he was wonderful.” And despite Patton’s yelling at the young “loootenant” that day at the Desert Training Center, Craig still liked Patton the man. “He was very strong willed, but we all admired him.”

My dad, Sergeant James P. Morris, from Fort Worth, Texas was a tank commander in WWII with General Patton; Patton would often ride with Dad in his tank. Dad had many great stories of General Patton, whom he admired greatly. At the first of Hitler’s Concentration Camps to be freed, Ohrdruf, dad was with General Patton. Dad had a chance to meet General Dwight Eisenhower and General Omar Bradley who also came to Ohrdruf. I have a photo of my dad with Eisenhower, where my dad was wearing Patton’s camera around his neck. Patton would have dad take photos so Patton could send them home to his wife. My dad loved General Patton and had the greatest respect for him.