By Simon Rees

Tired, battered, and bruised, the Spaniards had put up a brave fight, but the enemy had proven too powerful. More than 5,000 had defended the fortress town of Ciudad Rodrigo, holding out for 10 weeks until resistance ended on July 10, 1810. Approximately 1,800 civilians and soldiers had been killed and thousands more wounded as Governor Andres de Herrasti sought terms. There was little more he could do as the fortress’ walls were now breached. Marshal Andre Massena, commander of the French Army of Portugal and Herrasti’s opponent, congratulated the governor for his men’s stout-hearted defense and granted them full honors in surrender. Massena’s force would soon grow to 65,000 men, and it was a step closer to invading Portugal with the goals of seizing Lisbon and crushing an Anglo-Portuguese army along the way.

Lieutenant General Arthur Wellesley, the Viscount Wellington, commanded this Allied force and had avoided relieving Ciudad Rodrigo because the French both outnumbered and outgunned him. With the exception of some skirmishing probes, his forces had remained beyond French striking distance. Wellington also knew Massena would have to take Almeida, another fortress town, to secure the main arterial route from Spain into Portugal. That was important because buying time was his most pressing concern as hundreds of engineers and pioneers, along with thousands of civilians, were busy constructing the Lines of Torres Vedras around Lisbon. These defenses would ensure there was no rerun of the grim Battle of Corunna fought on January 16, 1809, when the British held off the French and evacuated northern Spain by sea after a grueling retreat. Massena knew nothing of the lines or how they were influencing Allied behavior.

Massena and his ambitious subordinates clashed repeatedly in the French camp, which had a detrimental effect on the army’s effectiveness. His apathetic speech on taking command two months earlier had hardly helped. “Gentlemen, I am here contrary to my own wish,” he said. “I begin to feel myself too old and too weary to go on active service. The Emperor says that I must and replied to the reasons for declining this post that I gave him by saying my reputation would suffice to end the war.” These were hardly words to inspire victory, let alone confidence. Massena had demonstrated his talents as a corps commander during Napoleon’s campaigns in central Europe the year before, particularly during the Battles of Aspern-Essling in May and Wagram in July. Indeed, Napoleon had conferred on him the title Prince d’Essling in recognition of his efforts. Nevertheless, this time Massena was undertaking an independent command thatcame with far greater challenges.

Born in 1758, Massena had served in the old royal army and then raced through the ranks of Revolutionary command during the mid-1790s. He had successfully campaigned across some of the Continent’s toughest terrain, scoring notable victories along the way. Gruff and direct, he was also avaricious. Napoleon had to censure him twice for egregious looting and expropriation in Italy. He had been blinded in the left eye, although not because of enemy action. According to Jean-Baptiste Marbot, an aide-de-camp, Massena had joined Napoleon and his entourage on a hunt, during which the emperor took a poor shot or misfired. Some of the pellets struck Massena’s face and, although left writhing in agony, he saved the emperor from further embarrassment by blaming Marshal Louis Berthier. Marbot’s memoirs offer a unique window on events, but it is important to note he was often biased against Massena, whom he thought played out by 1810.

Wellington responded to Ciudad Rodrigo’s fall by ordering most of his forces to retire west of the River Coa in the Portuguese frontier region with Spain. Brig. Gen. Robert Craufurd’s Light Division was kept on the eastern side to act as a screening force and thwart any potential coup de main against Almeida. But any action would probably be limited in scope and most likely involve a quick withdrawal given the expected size of the approaching enemy. “I am not desirous of engaging in an affair beyond the Coa,” wrote Wellington to Craufurd on July 22, underlining his view that battle was best avoided. However, the Allied commander left the final decision to an experienced subordinate whose primary concern had to be Almeida’s initial safety.

The Light Division was deployed on a northeast-southwest axis for several miles, starting with a half battalion from the 95th Foot deployed south of Almeida. The regiment was composed of specialist skirmishers famed for their Baker rifles and nicknamed the Green Jackets because of their dark green uniforms. The center was held by battalions from the 43rd Foot and the Portuguese 1st and 3rd Cacadores, while the 52nd Foot held the southwest and was closest to the Coa. Craufurd had 4,200 infantrymen with several hundred cavalrymen and a fair number of guns in sup- port. The terrain was latticed with earthen walls that marked various rural boundary lines, while a road ran behind Allied positions before passing a bridge over the river. The Coa has precipitous sides and it was in full flow on the night of July 23 because of torrential rains, rendering its small number of fords unusable the next day.

Reconnaissance units from the French VI Corps arrived on July 24 and soon reported back to their commander, Marshal Michel Ney, who correctly guessed his enemy had little room to maneuver or retreat. With typical vigor, he ordered squadrons from the French 15th Chasseurs and 3rd Hussars to push forward and pin any Allied units near Almeida. Two divisions under the respective leadership of Maj. Gen. Louis Loison and Brig. Gen. Claude Ferey would follow, striking the Light Division’s center and aiming for the bridge. Enemy units that failed to cross would then be destroyed at leisure. The French outnumbered Craufurd more than two to one and a withdrawal should have been initiated as the scale of opposing forces became apparent. Nevertheless, Craufurd decided to hold his ground, a failure in judgment with fateful implications for many Allied soldiers that day.

The weight of the initial attack fell on the 95th, with one of its companies caught in the open and badly cut up by French cavalry, while another contingent suffered friendly fire when Almeida’s defenders mistook their uniforms for those of the enemy’s. It took support from the 43rd to create a temporary stalemate. Craufurd issued belated orders to retreat over the bridge, with Allied cavalry and artillery instructed to move first. But the withdrawal was poorly organized and the Portuguese 1st Cacadores reached the crossing first, causing a bottleneck behind. The bridge was constructed almost as a hairpin in the road, which was fine for lazy rural traffic but a nightmare for hundreds of soldiers and animals. Matters were made more difficult by an artillery caisson overturning on the approach and taking up precious road space.

The French were advanced in force, and a strong screen of their tirailleurs and voltigeurs, both of which were light infantry used for skirmishing, were harrying the defenders as they pulled back, although both sides were slowed by the earthen walls. Fortunately for Craufurd, the difficulties at the bridge were soon resolved and his units started crossing and deploying on the western side at a steadier pace. On the east side, the 95th and 43rd were holding a nearby hillock and covering the withdrawal until they were also ordered to retire. That was a mistake as five companies from the 52nd had yet to reach safety and were soon spotted racing along the river bank toward the bridge just as French units were closing in on them. Riflemen and units from the 43rd rushed back over and, with the help of the 52nd, managed to create another momentary stalemate. The remaining Allied forces then crossed, although the final rear guard was less lucky and many of its men were shot down in the last dash for safety.

The Light Division had escaped by the skin of its teeth, and Ney was keen to further harry Craufurd’s men. He ordered the French 66th Line Infantry to force the crossing, resulting in a slaughter as the bridge both funneled and compressed the attackers, exposing them to fire from the front and sides. Three efforts were made by various contingents and included a 10- minute period when an estimated 240 casualties were inflicted. A truce was eventually called to gather the wounded, with Ney bringing the battle to a close shortly afterward. “It was a piece of unpardonable butchery,” Captain Jonathan Leach of the 95th Rifles wrote of the 66th’s attack. He was impressed by their bravery, but appalled by the wanton order to attack an almost impossible position.

Ney reported 530 casualties, leaving Massena both annoyed and concerned that the losses were too large to merit the results obtained. His official communiqués redacted some of the numbers and dwelled instead on a victory achieved so soon after Ciudad Rodrigo.

The Allies’ response was to stress the virtue of cool heads in a crisis. “The retreat was so well covered and protected by the excellent disposition of the troops forming the rearguard that we may, without being accused of vanity or bravado, look back upon it as a day of glory and not of defeat,” Leach wrote. That is a deceptive analysis, for the battle was nearly a disaster for the Light Division, which tallied rather conservative losses at 36 killed, 273 wounded, and 83 missing. The French recorded 300 Allied dead, 500 wounded, and 100 prisoners, while the imperial mouthpiece Le Moniteur beefed this up to hundreds captured, 60 Allied officers dead, and 1,200 other ranks killed or wounded. Craufurd was lucky not to suffer a severe reprimand as Wellington was a good judge of capability and knew when to extend the benefit of the doubt. Others were less sure and the Light Division’s commander took the somewhat unusual step of defending himself in The Times. He also gave the impression that his men had fought off the bulk of Ney’s 24,000-strong VI Corps, neatly highlighting how this was also a war of propaganda.

The French then laid siege to Almeida, with Massena worrying about his supply lines and increased guerrilla activity. His difficulties were compounded by missing matériel or sub-standard rations because of fraud among the quartermasters and corrupt contractors, which meant more foraging was required. That was often a euphemism for seizing local produce and leaving the inhabitants who remained in the war zone to face starvation. Frenchmen captured by partisans or the Portuguese militia, the Ordenanza, were tortured or killed because of this suffering. The French carried out various kinds of violent counterreprisals, including arbitrary executions, although Massena tried to maintain the façade of popular liberation. “We enter your territory not as conquerors. We do not come to make war on you, but to fight those who force you to make it,” he bombastically proclaimed.

Almeida was defended by Colonel William Cox, who commanded 4,000 Portuguese troops. The heart of the defense was a medieval castle used to store the munitions and powder, while ample rations were held in locations across the town. Massena’s men started constructing siege works from mid-August, with the full weight of bombardment beginning on August 26. No one could have predicted what happened next: the defenders’ powder and a huge volume of cartridges blew up the following evening. Speculation is rife as to the cause, with some wondering if a French cannonball had ricocheted into the magazine and sparked some loose powder. Bricks, beams, smashed tiles and other detritus were hurled through the air, even killing some of the besiegers. Fires were ignited, creating an inferno that burned in the town’s heart into the following day.

Approximately 800 defenders were killed along with hundreds of civilians. It would have been impossible to fight beyond a day or two without the necessary ammunition, so Cox capitulated on August 28. The bulk of Almeida’s stores and consumables had survived and were promptly seized. To the disgust of their officers, a large number of defenders volunteered to join the French, although they were probably the canny ones as most deserted in the following weeks and promptly rejoined the Allied ranks. The others were marched off for years of grim captivity. Almeida’s fall was a major blow for Wellington, who had hoped it would resist for at least 90 days, disrupting Massena’s schedule and forcing him to consider advancing over poor roads in autumnal weather. It also would have given him more time for completing the Lines of Torres Vedras.

The French spent several weeks preparing for the next phase of the invasion, with all units finally underway by September 15. Approximately 2,000 men had already been lost to the campaign and approximately 6,000 men were recorded sick, although these numbers were not unexpected because disease and lengthy recovery times were the norm during the Napoleonic wars. It was the atrocious state of the maps that shocked them most as they were a generation out of date and littered with mistakes. Marked roads often proved to be dusty tracks, while hills suddenly became mountains. The artillery and supply units suffered most as their horses and mules heaved guns, caissons, and carts along poorly chosen routes over increasingly rugged terrain.

The Allies fell back and believed the French would advance by using the main route southwest from Celorico to Coimbra. Scouts reported the enemy seemed to be aiming for Viseu to the northwest, which appeared counterintuitive because the French would have to overcome atrocious ground to reach the town. The British had to discern whether the movement was perhaps a pow- erful and cunning feint. Concerns in that quarter were laid to rest on September 17 when intelligence definitively reported the French Army of Portugal marching on Viseu. Massena’s decision was prompted by a combination of factors, including the desultory maps, poor reconnaissance, and a desire to find improved foraging opportunities. “Worse roads could not be found,” he rued shortly afterward. “They bristle with rocks. The artillery and wagons have suffered severely.”

French misery was compounded by surprise attacks. This included an audacious strike by Colonel Sir Nicholas Trant and his Ordenanza units on September 20 against the French artillery train no less. The French repulsed the attack, but it underlined the need to properly protect the guns and ancillary units, all of which added to Massena’s logistical headaches. His army straggled into Viseu over a 48-hour period beginning on September 18, finding it deserted and stripped of supplies.

The artillery and cavalry reserve had still not reached the town by the time Ney’s VI Corps moved forward on September 22, while Massena decided to halt his exhausted headquarters staff. Salacious gossips noted that Madam Leberton, his accompanying mistress, was playing a particularly important role in his rest and recuperation. The army was fully on the march by September 25, heading west-by-southwest just as Ney’s vanguard units approached Bussaco ridge, where they discovered a strong Allied force waiting to give battle.

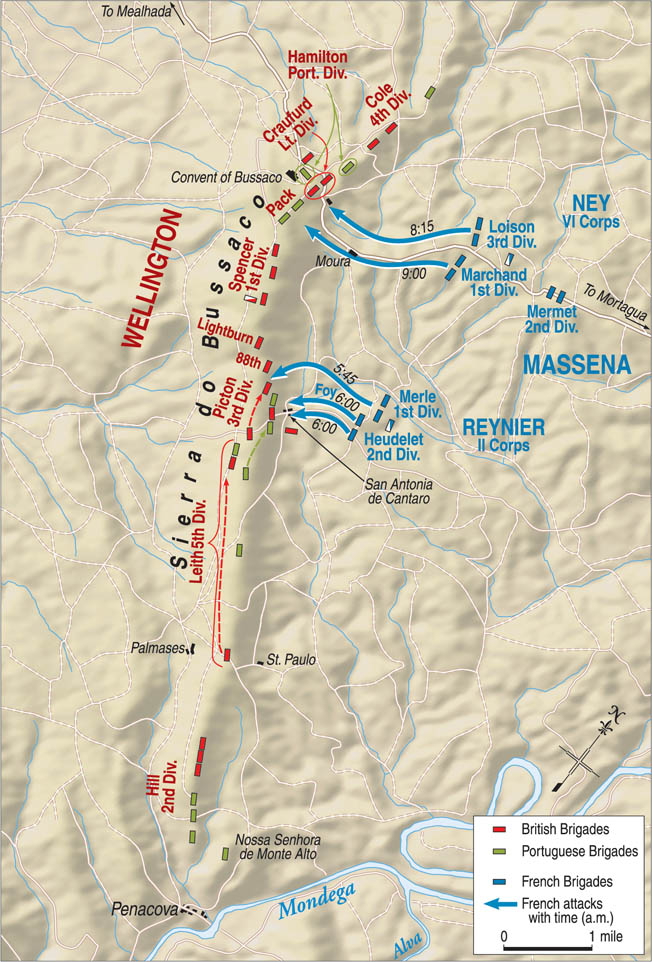

The French saw nearly the entire Anglo-Portuguese army arrayed before them. Wellington noted in correspondence on September 21 that Bussaco was a particularly strong spot for defense. “We have an excellent position here in which I am strongly tempted to give battle,” he wrote. Today the area is called Serra do Buçaco, a wooded ridge that peaks at 1,800 feet and is topped by a fairly broad plateau. It extends south to north and then northeast for several miles, with plenty of rocky outcrops in between. In 1810 there were far fewer trees and much clearer vistas. It was also a more sparsely populated location, with a Carmelite religious house located to the center north. Two roads crossed Bussaco ridge, the most important of which ran close to the village of Sula in the north, the other via San Antonio in the center. Several routes also led from the hamlet of Moura, just southeast of Sula, although most of these seemed fit only for muleteers or goat herders.

The Allied army totaled 50,000 men, with both Britain and Portugal contributing roughly equal numbers. Most of the Portuguese soldiers were untested but eager to fight, having undergone a comprehensive training program directed by Marshal William Beresford. British officers were also recruited into Portuguese units to further assist and quicken Allied integration. The French continued to discount these men based on previous engagements that had shown them poorly led and prone to breaking. There was also a strong German presence in the Allied ranks, including a brigade of the King’s German Legion in the 1st Division and some artillery contingents. Wellington had 66 guns of various calibers that he spread out in small batches to cover the areas Massena was most likely to attack. Engineers and pioneers had also built a rudimentary road along much of the plateau to enable unengaged forces to move up in support.

Two squadrons of dragoons were positioned on this road. Officers had ordered the rest of the cavalry to stand down because the craggy terrain precluded their deployment. An 820-man battalion from the Loyal Lusitanian Legion was positioned to the south to watch over the Mondego River, a natural barrier that protected the southern flank. Maj. Gen. Rowland Hill’s 2nd Division of 10,700 men was positioned to their immediate north followed by Maj. Gen. James Leith’s 5th Division of 6,500 men. Maj. Gen. Thomas Picton’s 3rd Division held the center with 4,700 soldiers and Maj. Gen. Brent Spencer’s 7,000-strong 1st Division controlled the north center. Three independent Portuguese brigades of 8,400 were nearest the convent, with Craufurd’s Light Division of 3,800 positioned in between and slightly ahead. Maj. Gen. Lowry Cole’s 4th Division of 4,700 anchored the ridge’s northeast end, while militia forces screened the areas beyond.

French efforts to guess Allied numbers were thwarted by the topography and a strong skirmish line that kept their reconnaissance units at bay. Wellington also banned the lighting of camp fires as their glare could help reveal the scale of his forces. That was a wise decision as the French were soon underestimating their opponent’s strength, with Loison guessing the Allied army numbered approximately 30,000. Ney arrived on the evening of September 25 and sent an aide-de-camp to request Massena’s urgent presence. He also conferred with Maj. Gen. Jean Reynier, the commander of II Corps, announcing he would have liked to attack what he initially believed to be a strong rear guard.

But most French forces were still arriving and needed time to prepare, while many other units would not reach the area until the following day. Left stewing for most of September 26, French commanders present became both frustrated and enthusiastic in equal measure, requesting Massena to order an attack almost immediately after his arrival later that afternoon.

Massena refused and announced battle would be given the following morning. The plan he formulated was relatively simple. Reynier’s II Corps would attack first, striking the ridge via the San Antonio route and then pushing north along the plateau toward Bussaco Convent. He ordered the deployment of strong rear guards to thwart any Allied relief efforts from the south. Key’s VI Corps would attack the center and north with two divisions on seeing II Corps progress, leaving a third division in immediate support. VIII Corps, comprising two divisions and under the command of Maj. Gen. Jean-Andoche Junot, would act as a general reserve. Its artillery would also assist Ney’s guns, although the high angles involved would make accurate fire almost impossible. Massena decided not to deploy his cavalry because of the rugged terrain. Orders were issued for the battle columns to form up 4:00 AM.

The plan seemed unimaginative to some of Massena’s staff officers. Why not use the remainder of September 26 to conduct further reconnaissance and find the Allies’ weak spots? Better yet, why not flank the Allies to the northwest and force them into a hurried realignment or retreat? Aide-de-camp Marbot recorded how he and chief of staff Brig. Gen. Joseph Fririon held a conversation positing this question loudly enough for the marshal to overhear. They wanted to draw him away from Major Jean-Jaques Pelet, a trusted aide-de-camp whose opinions were usually heeded above others, much to their chagrin. Massena took the bait, ambled over, and joined the discussion. He seemed to agree with Fririon and ordered the north reconnoitered in more detail, with Marbot writing that he and some others discovered a road that appeared suitable for a wide flanking maneuver.

Marbot hurried back with the good news and Fririon presented the findings to Massena. But Pelet interjected that no roads were marked on the maps and that he had examined the area by telescope and seen no evidence of them. In addition, Ney had not reported any worthwhile routes, despite being in the vicinity for some time. “In vain did General Fririon beg the marshal to accept this offer,” Marbot wrote. “All was useless.” Increasingly frustrated by the entreaties, the French commander’s final retort was typically bluff. “You come from the old Army of the Rhine, you like maneuvering; it is the first time that Wellington seems ready to give battle, and I want to profit by that opportunity,” Massena said. He apparently voiced regret to Fririon some hours later, admitting he should have considered further reconnaissance to at least confirm the road’s value. But it was too late, and the battle would have to go ahead as planned.

The early hours of September 27 were misty, offering useful cover as Reynier’s two divisions formed into columns under the respective commands of Generals Pierre Merle and Etienne Heudelet. Their advance started at 5:45 AM with artillery firing blind at suspected targets over the lead columns. Little damage was done as Allied forces hunkered down in defensive positions or waited behind reverse slopes. Heudelet’s 8,000-strong division used the route from San Antonio, its skirmishers clashing with enemy light companies from Allied 3rd Division’s 45th, 74th, and 88th Foot Regiments. Picton sent over additional men from the 45th and some from the 8th Portuguese Regiment to support the 88th as the firing intensified nearest its front. The French found the approach tiring. Their difficulties were compounded by the odd British cannonball careening down the slopes to crush, mutilate, or knock men over like rag dolls.

The French 31st Light Infantry closed in on the Allies first, finding themselves opposed by men of the 74th Foot and 21st Portuguese Regiment. The Portuguese soldier not only stood his ground but also let the French come in close before delivering steady, well-fired volleys. Somewhat bemused their enemy was not wavering or retreating as he had so often done in the past, the French also struggled to hold formation because of the uneven ground and incoming musket balls, the damage from which could be horrendous to the human frame. The same resistance was met elsewhere along this stretch of the Allied line and few troops could withstand such a beating for long. Heudelet’s men were no exception and withdrew out of small arms range.

Other fighting had erupted as Merle’s force of 6,500 men came into range less than a mile to the north. The conditions and mist now worked against the French as the attackers were disoriented during their approach. Many of them fell away from the main body, including a large group of men who inadvertently found themselves on the ridge’s crest having marched between the 45th and the 8th Portuguese. It was too good an opportunity to waste and the French soldiers clung on, limpet-like, while causing a supporting Portuguese militia unit to flee. Colonel Alexander Wallace from the 88th noted the threat and raced over with three companies. It was essential to push the French back or their comrades behind would come up in support and threaten a break- through. “Don’t give them the false touch but push home to the muzzle!” Wallace shouted, urg- ing his men to make full use of the bayonet when charging.

Men from the 45th’s left flank had joined the 88th in their charge against the French 36th and 70th Line Infantry Regiments. The subsequent hand-to-hand fighting was fiercely contested, although Allied troops had the benefit of being comparatively fresh and being in tighter formation. “All was now confusion and uproar, smoke, fire, bullets, officers and soldiers, French drummers and drums knocked down in every direction,” wrote William Grattan, an ensign with the 88th.

The enemy broke with the 45th, 88th, and some of the 8th Portuguese hot on their heels until they came within French artillery range and retired back up the ridge. “I have never witnessed a more gallant charge,” said Wellington, who rode up to Wallace after the units had returned and congratulated him.

It was a good start for the Allies but there was plenty more fighting ahead. Reynier ordered French Brig. Gen. Foy to attack and seize another foothold. The soldiers of the French 17th Light Infantry and the 70th Line Infantry formed up and pressed forward with their commanding officer in the lead. They reached the crest to find the battalions of the 8th and 9th Portuguese Regiments waiting for them, supported by elements of the 45th Foot. The weight of French numbers was telling here and they started to push the Allies back. However, fortune continued to favor Wellington as General Leith had decided to move his 5th Division northward on hearing the sounds of battle in Picton’s vicinity. Men of the 1st, 9th, and 38th Foot Regiments struck into the rear and left flank of the French not long after they had secured their position.

Foy must have thought he was prying open the doors to victory until Leith’s men slammed it shut. “[The enemy] on our left made a movement and we were overwhelmed with battalion fire,” he recalled. “Upon our front the enemy, hidden behind rocks, assassinated us with impunity.” Foy attempted to rally his men as they started to waver, a task made more difficult after being shot in the arm. “At this moment a ball went through my left arm, breaking it,” he said. “I was swept away in the flight.” The Allies had charged after several volleys, breaking the French will to resist and sending them running pell-mell down the slopes. Again Anglo-Portuguese troops pursued until coming within range of the French guns, whereupon they retired to rejoin the Allied lines. Reynier’s corps had been mauled, with more than 2,000 casualties taken, the dead and severely wounded littering the ground.

It was now Ney’s turn. He had spotted Merle’s column closing on the ridge and thought Reynier’s corps was now working its way northward as planned. Loison’s division was promptly unleashed to attack Sula and the slopes beyond, while Marchand’s division aimed for Bussaco Convent using a small road out of Moura. The units were separated by a steep ravine, with Marchand’s men having the better ground. They came under Allied artillery fire just beyond Moura, the lead elements also having trouble from 4th Cacadores sharpshooters firing down from some nearby pine trees. The lead brigade under Brig. Gen. Antoine de Maucune eventually came face to face with the 1st and 16th Portuguese Regiments, which also held firm and delivered solid volleys. Maucune was wounded at this point and his unit ground to a halt, with Brig. Gen. Pierre-Louis de Marcognet’s brigade behind doing likewise. There seemed little option now but to wait for the Allies to crack elsewhere.

Loison’s corresponding advance had faced difficulties from the start. The ground was decidedly rough. French skirmishers also found it hard to dislodge their enemy counter- parts, the Light Division men from the 95th and the 3rd and 4th Cacadores. Indeed, such was the opposition that Loison sent line infantry to assist. Sula was taken soon after- ward, with Allied artillery fire starting once French forces moved beyond. The gradient steepened considerably, exhausting the men who were struggling to maintain formation. It took an immense amount of stamina and courage but Loison’s troops had crested a smaller ridge and noted the main heights were now tantalizingly close. Many of them were aiming for a windmill just ahead, the enemy skirmishers seemingly bested and some nearby guns looking ripe for the taking.

It was at this point that 1,750 troops from the 43rd and 52nd of the Light Division suddenly rose up from concealed positions in a nearby sunken road. Craufurd was waving his hat as a pre-arranged signal for this maneuver and the men now steadied themselves to fire. “Now 52nd, avenge the death of Sir John Moore!” he shouted. Craufurd was referring to the Battle of Corunna in which Moore, the British commander at that time, had been mortally wounded. Moore had also helped convert the 52nd into light infantry in 1803 and was a fondly remembered leader and mentor. The enemy’s front ranks were lacerated by the initial volley, with the soldiers behind becoming jumbled and disorganized in the frantic effort to form their own firing line. Some of the French had pushed for- ward instead, including a contingent led by Brig. Gen. Edouard Simon who was badly wounded in the jaw during the fighting.

Craufurd’s men extended their line to create a greater frontage, with men from the 3rd Cacadores and the 95th Rifles assisting. Loison’s division withstood the murderous fire for a few minutes but fled when the Allies charged. “It was a carnage not a conflict,” wrote a British artillery officer. They chased the French as far as Sula before pulling back, with General Simon having been found and captured by a private from the 52nd. A notable side incident to this attack involved the 2nd Battalion of the French 32nd Light Infantry, which had become separated in the advance. It was checked and then routed by a battalion of the 19th Portuguese Regiment, the latter pursuing its foe and then reforming with almost parade ground precision. The movement was carried out with such aplomb that some nearby Allied units spontaneously cheered this proof of growing professionalism.

Loison lost 21 officers killed and 47 wounded, with an estimated 1,200 casualties in total. Marchand’s division had taken 1,150 casualties by the time it was ordered to withdraw by Ney, who realized further attacks would be futile. Massena was in agreement and ordered all units to disengage shortly afterward, having spent most of the battle watching events unfold from a wind-mill near Moura. The French tallied 522 killed, 3,612 wounded, and 364 missing from II and VI Corps, with approximately 100 casualties from other units. The damage may have been much greater. The Allies reported 200 dead, 1,000 wounded, and 50 missing, with the casualties roughly half British and half Portuguese and, to some extent, reflecting the levels of integration within Wellington’s army. Despite the drubbing, Massena still had more than enough men to continue the invasion and he was soon using the northwest route Fririon had urged on the eve of battle. The French reached Sardao by September 28. From Sardao, they turned south toward Coimbra.

Marbot bitterly regretted Massena’s failure to heed Fririon, although Ney should share some of the blame for the failings at Bussaco. He had from the afternoon of September 25 until the night of September 26 to achieve a more thorough reconnaissance rather than just test the Allied skirmish lines. Indeed, Ney, Junot, Reynier, and others seemed content to underestimate their enemy and wait for Massena’s arrival, whereupon they urged him to attack. It was behavior that high-lighted a critical French weakness: disunity at the command level as Massena kept trying to stamp his authority over a group of men who, to varying degrees, often thought they knew best. However, the ultimate decision to give battle rested solely with him. In addition, a commander of his stature should have formulated a better plan than two frontal attacks up a steep ridge against an enemy given several uninterrupted days to prepare its defense.

Wellington’s miscalculation was a failure to cover the approaches on his northern flank. But he swiftly recognized the threat and ordered a westward retreat, with supplies and harvested crops destroyed along the way. The Allied commander wanted to create an artificial desert for Massena to follow him into. Civilians were also told to leave the war zone and August Schaumann, an officer in Wellington’s commissary, recorded the depressing retreat. “Every division was accompanied by a body of refugees,” he wrote. “Despair was written on all faces. It was a heart-rending sight.” The Allies withdrew through Coimbra at the end of September, with all units reaching the near complete Lines of Torres Vedras by October 9. It was a low point, but at least Wellington could look on Bussaco with satisfaction. The French army had been beaten and the Portuguese had proven their mettle, helping to boost national morale. “[Victory] has given them a taste for an amusement to which they were not before accustomed, and which they would not have acquired if I had not put them in a very strong position,” he wrote.

Massena’s men entered Coimbra on October 1 and engaged in an orgy of destruction. Many of the remaining civilians were maltreated, assaulted, or murdered, with the city’s bishop estimating that almost 3,000 were killed. Even if that number was exaggerated, hundreds were almost certainly butchered, representing an indelible blot on Massena’s career. The French began their final pursuit of the Allies on October 4, although Trant’s forces came in behind and seized Coimbra, taking prisoner almost 4,500 wounded, service staff, and a woefully small garrison. He managed to protect these men from local vengeance and had most transported to Oporto under guard. A handful of Frenchmen were seized by angry civilians and lynched, their deaths prompting rumors that a massacre had taken place and compounding the criticism that Massena should have left more units to defend Coimbra in the first place. Nonetheless, morale remained fair as it appeared the grueling campaign was entering its final phase.

Enemy prisoners captured during the French advance on Lisbon noted the Allies were aiming for the Lines of Torres Vedras ahead of the capital, which meant nothing to Massena or his staff, who guessed these were probably hastily arranged static positions. French vanguard elements discovered the unwelcome truth on October 11. They found that the Lines of Torres Vedras was a formidable series of interlinked forts, redoubts, and shelters that stretched across the peninsula between the Atlantic Ocean and the broad mouth of the River Tagus with Lisbon safely behind them. After some sharp fighting on October 13 that went nowhere, Massena arrived and surveyed the scene on the following day. It seemed inconceivable to him as French intelligence had reported nothing approximating the Lines, while his subordinates also appeared dumbfounded. Massena’s outburst said it all: “What devilry! Wellington didn’t make these mountains!”

He may not have made the mountains, but Wellington had made the fortifications. Altogether he spent 200,000 pounds fortifying the approaches to Lisbon. The Lines of Torres Vedras proved its worth immediately as the French remained in the vicinity, stuck trying to find a solution to this unexpected impasse. The defenses were simply too strong to storm, while the Royal Navy and Britain’s merchant fleet ensured a constant resupply for the besieged. That was in stark contrast to the besiegers who found themselves in a region without provisions, at the end of broken supply lines, and no longer in regular contact with French forces in Spain.

Massena withdrew his army to Santarem on the Tagus by mid-November, hoping to improve the situation. It was a dismal end to a campaign that was meant to have culminated in Lisbon’s seizure and the thanks of a grateful emperor; instead, his forces now battled starvation and an unseasonably cold winter, with thousands succumbing to the miserable conditions. Although nobody knew it, Bussaco was the high water mark of French intervention in the Iberian Peninsula, and Massena might have changed the course of history had he flanked instead of fought.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments