By Victor Kamenir

In 1242, Russian Prince Alexander Nevsky faced the armored might of the Teutonic knights. Generals Alexander Suvorov and Peter Kotlyarevski were Napoleon’s contemporaries, while General Mikhail Skobelev exemplified the panache of the Victorian Era. Nevsky, Suvorov, and Skobelev have gained international renown, while Kotlyarevski remain obscure even in modern Russia.

Among them, the four Russian commanders won many battles, large and small, and received dozens of wounds for their country. Yet not one of them fell on the field of battle.

They faced some of the greatest foes to challenge Russian might, including Swedish raiders, German knights, Ottoman janissaries, Polish lancers, and Napoleon’s grenadiers.

Scions of a military caste or coming from humble beginnings, the four military leaders made invaluable contributions not only to the development of Russian military science, but also to the development of the Russian state. For example, Nevsky was a skilled politician, practicing the art of realpolitik centuries before the word was invented, and Suvorov influenced Russian military thought and doctrine into the 21th century and expanded prestige of Russian arms into Western Europe.

Their personal bravery, unswerving commitment to their goals, and the care they showed for the welfare of their people rested on the unshakable bedrock of loyalty and love for their country.

Alexander Nevsky

Alexander Nevsky, the second son of Prince Yaroslav, was born in 1221 to a country torn apart by internal strife and threatened by foreign enemies. Thirteenth-century Russia was a mosaic of fiercely independent feudal duchies each ruled by a prince, or knyaz. Unique among them was the Republic of Novgorod, located near the Baltic Sea in northwestern Russia. While electing their own civilian administration officials, Novgorod’s assembly invited members of neighboring princely families to be its military commanders. In 1238, Yaroslav ascended to throne of the Grand Duchy of Vladimir, the preeminent Russian duchy, with the position of the Prince of Novgorod going to his teenage son Alexander.

Tutored from a very early age to be a warrior, Nevsky soon received an opportunity to show his mettle. During the 12th and 13th centuries, Novgorod and Sweden were engaged in a series of wars for control of the territory surrounding the Gulf of Finland. At the same time, Novgorod was fighting off encroachments by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword in the area of the modern-day Baltic States of Estonia and Latvia. When the Sword Brethren, as they were called, were decimated in a battle with the pagan Kurs in 1236, they merged with the much larger Order of the Hospital of St. Mary of the Germans of Jerusalem (Teutonic Knights).

In early July 1240, a fleet of Swedish longships entered the mouth of the Neva River from the Gulf of Finland. The fleet was quickly spotted by coastal watchers of the Izhora tribe, allied with Novgorod, and kept under constant observation as it continued east along the river. In all likelihood the Swedish intent was to navigate the Neva River to Lake Ladoga and then descend the Volkhov River to the city of Novgorod. Upon receiving news of the enemy, Nevsky did not wait for the full mobilization of the Novgorod militia or request assistance from his father. He quickly moved north to Lake Ladoga with only his household cavalry and that of his nobles, where he was joined by Ladoga and Izhora levies.

The Swedish fleet disembarked at the confluence of the Neva and Izhora Rivers, almost 100 miles north of Novgorod. Unaware of any significant Russian forces in the area and with their camp secured on two sides by the two rivers, the Swedish carelessly did not post adequate sentries. On July 15, the Russians attacked and penetrated deep into the Swedish camp. Nevsky was in the thick of fighting. The valiant warrior is believed to have left a mark with his spear on the face of the Swedish commander.

Despite the initial confusion, the enemy troops rallied and were able to repulse the attack. Once the Russians withdrew, the Swedish and their allies reboarded their ships and retreated west along the Neva River. Details about the numbers of participants and their casualties are sketchy. The Russians likely numbered fewer than 2,000 men, while the Swedish possibly fielded twice that number. Russian casualties were said to be very light. As was customary at that time, however, only the fallen professional warriors were mentioned; casualties among the levies were not counted. Likewise, Swedish casualties are vaguely described as high as several hundred.

After victorious Nevsky returned to Novgorod, the gratitude of the city fathers did not last long and in late 1240 Nevsky left the city. A new threat to Novgorod, however, was looming in the west. Even before Nevsky’s departure, the Teutonic Knights advanced on Novgorod, capturing its vassal city of Pskov. Only after the Germans approached within 20 miles of Novgorod in early 1241 did the city council appeal to Nevsky to return.

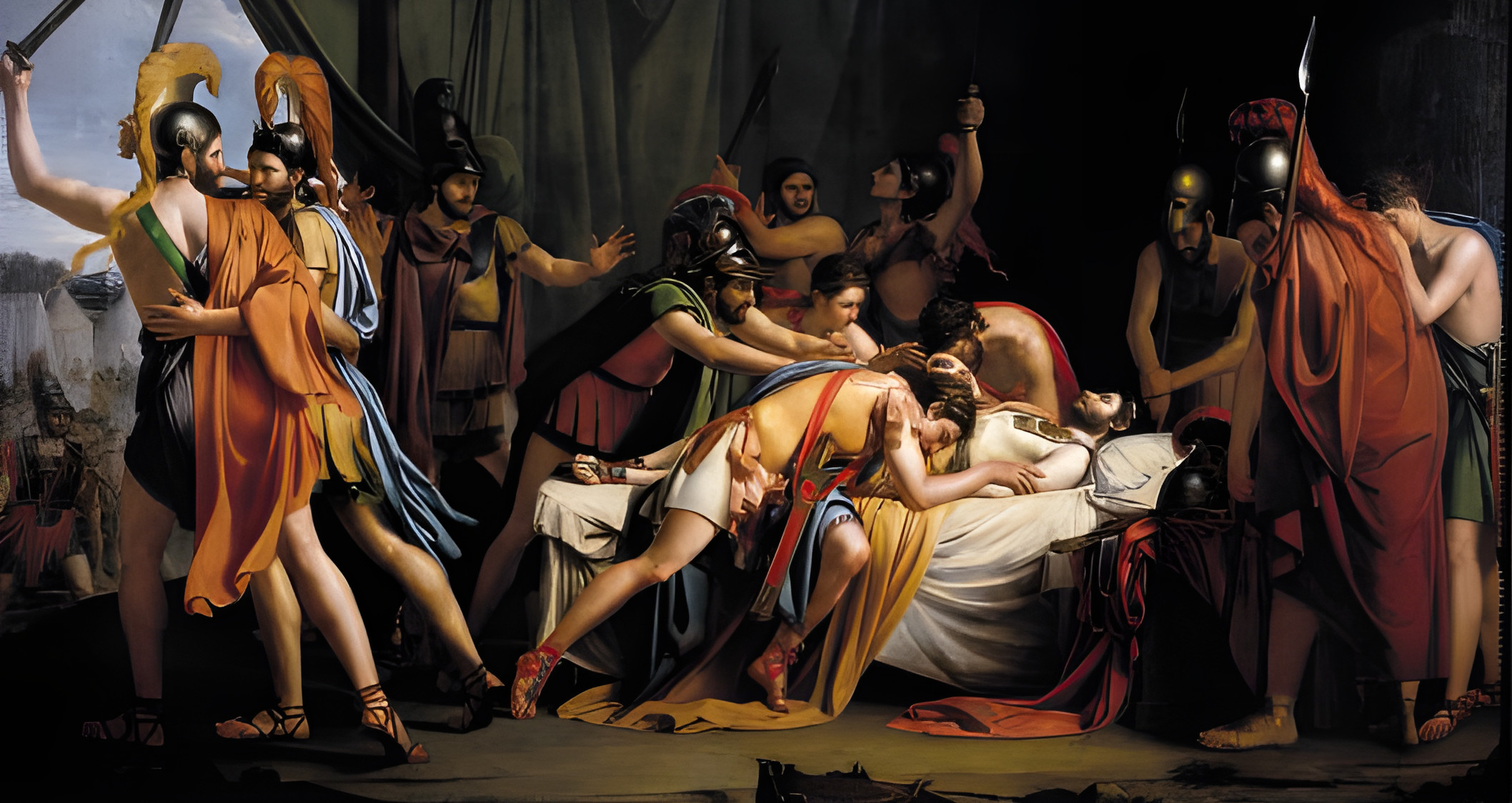

Throughout 1241, Russian forces under Nevsky’s leadership cleared the Pskov lands and invaded the territory of the Teutonic Knights in early 1242. After the leading Russian detachment was defeated on April 5, 1242, Nevsky concentrated his forces at a cluster of three lakes that form the modern-day border between Estonia and Russia. The winter was harsh and there was a thick layer of ice over most of the lakes, presenting the only flat surface in the area. Nevsky deployed his forces on the ice at the south end of Lake Peipus, the northern most of the three.

Details of the Russian deployment are scarce. In the typical fashion of the day, Russian forces would have been deployed with a large main regiment in the center composed of infantry. On the flanks would be cavalry under Nevksy himself. It is known, however, that a thick screen of archers and crossbowmen was deployed in front of the main body.

The Teutonic Knights deployed in their typical fashion as well, the Schweinkopt, the “Pig’s Head.” This formation was designed for maximum shock effect. Heavily armored knights formed a wedge at the front of the column. This formation allowed the knights on the flanks to be protected by those in the rank behind them. The knights were followed by a block of mounted men-at-arms and retainers. Immediately behind the Germans came allied Chud (pronounced chood) tribesmen, stiffened with some German soldiers. The exact strength of combatants is unknown. Sources vary greatly, citing from 4,000 to more than 15,000 men on each side.

As the Germans advanced across the ice, they were met with volleys from Russian archers and bowmen, who then fell back toward their main body. As the Germans drove into the central Russian regiment, its flanks began to extend to envelope the enemy. At the critical moment, Nevsky gave the command and the Russian cavalry fell upon the Germans and the Chud from both flanks. After a short struggle, the enemy was routed. Some of the Germans attempted to escape to the south, where a number of them fell through the thinner ice over the Warm Lake. This decisive defeat put an end to Teutonic expansion to the east.

Between 1237 and 1240, the majority of the Russian duchies succumbed to the Mongol invasion. However, unlike their conquests in Asia, the Mongols did not absorb the Russian territories into their empire, but granted them the status of vassal states, content with gathering tribute and enlisting Russian levies for various campaigns. Rival Russian princes vied against each for favors from Mongol rulers.

After his father Yaroslav died in 1246, rumored to have been poisoned, shortly after visiting the Mongol Golden Horde, Nevsky walked the knife’s edge of armed politics among various Russian factions and the Mongols. In 1252, he was installed by the Mongols as the Grand Prince of Vladimir, supreme among Russian rulers. Some modern Russian historians criticize Alexander as being too subservient to the Mongols, but he was able to keep the northern Russian territories from being invaded.

While visiting the Golden Horde in 1263, Nevsky became ill. It was rumored that Nevsky was poisoned in retaliation for his protection of the Russian rebels who murdered Mongol tax collectors and recruiters. Nevsky died on November 14 on his way back from the Golden Horde, taking monastic vows on his deathbed. The name of Nevsky (which means “of the Neva”) is greatly revered in Russia. In 1574, the Russian Orthodox Church canonized Nevsky as a saint.

Alexander Suvorov

In 1730, a son was born to Lt. Col. Vasili Suvorov. The father, who eventually rose to the ranks of a full general and a senator, was a great admirer of Alexander Nevsky and named his son after his hero.

Alexander Suvorov was a small, sickly child and his father resigned himself to the realization that his son was unfit for military service. Despite his father’s decision, young Alexander set his mind on the military.

Fate intervened in 1742 when General Abram Hannibal visited the elder Suvorov. Both Hannibal and Suvorov were godsons and former aides-de-camp of Czar Peter the Great. Hannibal was so impressed with the intelligent and quick-witted Alexander that he talked Suvorov into allowing the boy to enter the military service.

The same year, the 12-year-old Suvorov enrolled as a private in the prestigious Semenovski Life-Guard Regiment in St. Petersburg, while also attending the Land Forces Cadet Corps.

Suvorov first saw combat during the Seven Years War, serving in a variety of combat, staff, and administrative postings. He rose to the rank of colonel in 1762 at the age of 32. Afterward, he served with distinction as a regimental commander during the war with Poland from 1769 to 1772, achieving the rank of major general in 1770.

It was in Russia’s wars against the Ottoman Turks that Suvorov gained fame that remains untarnished until this day. Suvorov developed his own style of fighting, based on shock and maneuver, diametrically opposing the linear tactics of his day. The training he continuously instilled in his troops brought handsome dividends against the brave but undisciplined forces of the Ottoman Empire, still clinging to outdated weapons and tactics.

Transferred to the Turkish front in 1774, Suvorov played a key role during the Battle of Kozludzha on June 20 in which an outnumbered Russian army routed a larger Turkish force. The battle decided the campaign and led the Ottoman government to sign a greatly unfavorable peace treaty.

When the next war with Turkey flared up in 1787, Suvorov was there, now a lieutenant general. One of the most important battles of the war took place on September 22, 1789, near the Rymnik River. Leading the allied Austro-Russian force numbering 25,000 men at the Battle of Rymnik, Suvorov attacked Turkish positions occupied by 100,000 troops. After suffering heavy losses from the initial Russian attack, the Turks rallied and launched multiple counterattacks against the allies. Each time, the impetuous Turkish charges were shattered by the disciplined volleys of Austrian and Russian troops. The fighting continued for 12 hours and ended up in the complete defeat of the Turkish army, which lost 15,000 men. In contrast, the Allies lost fewer than 1,000 men. For his victory at Rymnik, Suvorov was elevated to the rank of count in both the Russian and Austrian nobilities with the addition of Rymnikski to his last name.

As the war continued, Russian forces besieged the strategic Izmail Fortress on the Danube River. The siege dragged on until the Russian commander-in-chief ordered Suvorov to take the fortress. Arriving there on December 12, 1790, Suvorov sent an ultimatum to the Turkish commander, demanding surrender. When the latter refused, Suvorov spent the following eight days training his forces for an assault, creating a practice camp complete with a ditch and a section of a wall similar to the ones surrounding Izmail.

After a day-long bombardment, Suvorov launched his forces against the fortress on December 22. After two hours of heavy fighting, Russian troops gained the fortress wall and the Turks retreated deeper into the city. Vicious house-to-house fighting lasted until mid-afternoon. In places, Russian artillery was brought into the city and fired grapeshot at point-blank range. Russian losses numbered more than 4,000 killed and 6,000 wounded. The Turks lost 26,000 killed, many of them civilians, and 9,000 taken prisoner.

Suvorov’s career suffered a setback after Czarina Catherine II died in November 1796. She was succeeded by her son Paul I, who was an ardent supporter of Prussian Frederick the Great. Paul I began reorganizing the Russian army on the Prussian model, giving it a new doctrine and uniforms. Endless drill replaced tactical training. Suvorov was an outspoken critic of the reforms, in particular the reinstitution of corporal punishment. Incensed with Suvorov’s criticism, the emperor dismissed Suvorov into a forced retirement in February 1797. The general was under constant police surveillance and he was not allowed to travel farther than a few miles from his residence.

The banishment, however, lasted only one year. The forces of revolutionary France were winning victory after victory in Europe, and the Austrian emperor requested that Suvorov be placed in command of the Austrian army. Reluctantly, Emperor Paul I dispatched Suvorov to Vienna. Arriving there in March 1798, Suvorov took command of the joint Austro-Russian army in northern Italy.

In a series of decisive battles, Suvorov defeated every French army sent against him. By the end of May 1799, most of northern Italy was swept clear of French forces. On August 19, Suvorov was elevated to the princely rank and was titled Prince Italiyski Count Suvorov-Rymnikski.

In early September, Suvorov was ordered to proceed to Switzerland over the Alps to link up with the Russian force under General Alexander Korsakov. Lacking a sufficient number of transport mules, Suvorov was forced to leave his artillery and most of his supplies behind as he entered the mountains. His every step was dogged by elements, treacherous terrain, and delaying tactics of French rear guards. After fighting his way through the St. Gothard Pass, Suvorov came upon the Devil’s Bridge, spanning a deep gorge over the Reuss River. Against heavy French resistance, Suvorov forced the bridge, finally arriving at Lake Lucerne where he learned of Korsakov’s defeat.

Suvorov’s force was exhausted, threadbare, starving, and nearly out of ammunition. The sexagenarian general was ill, having shared all privations with his men. Multiple French divisions, totaling 80,000 men, were closing in on Suvorov’s 23,000-man army. With heavy heart, Suvorov ordered the retreat northeast to Austria. Time and time again, running out of ammunition, the Russian soldiers counterattacked with bayonets, driving the French back. In early October 1799, Suvorov reached Austrian territory, ending the campaign.

Exhausted and sick, Suvorov returned to St. Petersburg in May 1800. Czar Paul I, still bearing him ill will, refused to see him. When Suvorov died on May 18, the czar did not attend his funeral. During the course of his illustrious career, Suvarov had fought more than 60 battles, all of which he won.

Peter Kotlyarevski

Peter Stepanovich Kotlyarevski was born a son a village priest in eastern Ukraine in 1782 and was set to follow in his father’s footsteps until fate intervened. A Russian officer, Lt. Col. Ivan P. Lazarev, traveling to a new assignment in the Caucasus Mountains, was forced to seek shelter at the church during a harsh winter storm in 1792. Lazarev was so impressed with the intelligent 10-year-old boy that he secured a posting for him in his own unit, the Caucasus Jaeger Corps. The next year, Kotlyarevski was enrolled as a private in the 4th Battalion, commanded by Lazarev. As was common at the time, well-born young men went up in ranks as they pursued their education. A year later, at the age of 12, Kotlyarevski became a sergeant.

The Russian forces in the Caucasus were engaged in constant warfare against rebellious mountain tribes, as well as resisting Turkish and Persian efforts to stem the Russian encroachment into their traditional spheres of influence south of the mountains. The fighting was vicious, with neither side giving nor asking quarter. In 1796, 14-year-old Kotlyarevski received his baptism of fire during the storming of the Persian fortress of Derbent on the shore of the Caspian Sea.

Kotlyarevski was promoted to ensign in 1799 and became aide-de-camp to Lazarev, now a major general. Sadly, their association soon came to a tragic end. In 1800, the Dowager Queen Mariam of Georgia, upset at Czar Paul’s I abolition of the Georgian monarchy, personally stabbed Lazarev to death when he arrived at the Georgian capital of Tiflis to remove her to Russia. The new commander of the Russian forces in the Caucasus offered Kotlyarevski a position as his personal aide-de-camp. Kotlyarevski declined, however, choosing instead to command a company in a jaeger regiment. Later in the year, now a captain, Kotlyarevski participated in the defense of Tiflis from a large force of rebellious Lezghin tribesmen.

In June 1805, a 40,000-strong Persian army invaded the territory of modern-day Azerbaijan. The advancing Persian vanguard ran into a small Russian detachment garrisoning a small ancient fort at the Askeran village, blocking the road in a narrow mountain pass. The 500 Russian soldiers, including Kotlyarevski’s company, augmented by local Armenian levies, held out for two weeks. As the ever-increasing Persian reinforcements made the Russian position untenable, loyal Armenians helped the Russians escape along mountain trails.

As the years went by, Kotlyarevski continued campaigning, steadily rising through the ranks and accumulating wounds. In 1807, at the age of 25, he was promoted to colonel and given command of a jaeger regiment.

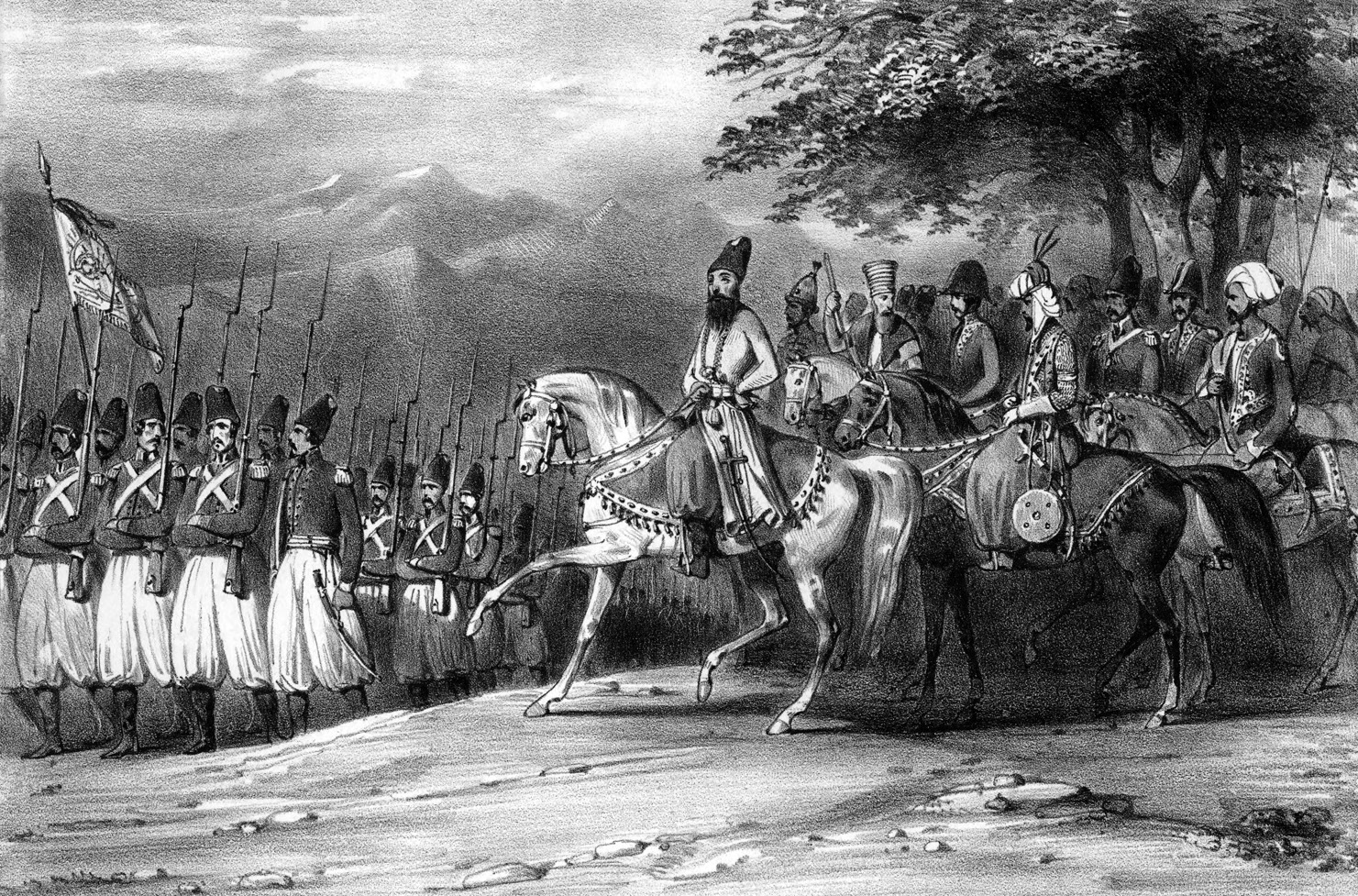

In 1810, a 30,000-strong Persian force led by Crown Prince Abbas-Mirza invaded the Karabakh Khanate, a protectorate of the Russian Empire. One of the leading Persian detachments occupied the Migri Fortress, strategically located at key crossroads. Colonel Kotlyarevski with a force of 400 jaegers and grenadiers was dispatched to retake the fortress.

Using local guides, Kotlyarevski led his men through difficult mountainous terrain and arrived in the immediate vicinity of Migri unobserved. A sudden Russian attack steadily cleared one outlying fortification after another, eventually forcing the bulk of the 2,000-man garrison to retreat from the fortress. Placing himself at the head of the attack, Kotlyarevski suffered a wound to his left arm. Two days later, Abbas-Mirza approached Migri with his main force. After several unsuccessful probes and finding the fortress too well defended to risk an assault, the Persian prince ordered his force to retreat back to the border.

But it was not in Kotlyarevski’s nature to let the enemy slip away unchallenged. Augmented by few local levies, he gave chase and caught up with the retreating Persian army as it was fording the Araks River at night. The Russian force of slightly more than 400 men was greatly outnumbered by the Persian host of more than 10,000. Knowing that any hesitation would be deadly and that no men could be spared to guard captives, Kotlyarevski ordered his men not to take any prisoners. A furious Russian bayonet attack exploding out of the darkness completely took the Persian forces by surprise. Disorder and panic swept through their ranks and the Persian army melted away.

The next year, 1811, Kotlyarevski executed another daring maneuver, taking two infantry battalions and 100 Cossacks through snow-covered mountains to capture the Akhalkalak Fortress by a night assault. For this audacious action, Kotlyarevski was promoted to major general.

In 1812, once again, Abbas-Mirza led a large army against the Russian-controlled territory. The thinly spread Russian forces could not garrison all the key points, and the Persians quickly occupied several strategic positions. Maj. Gen. Kotlyarevski was given authority to operate on his own initiative to recapture the territory. The force under his command numbered 2,200 men and six cannons; they faced roughly 30,000 Persians.

Crossing the Araks River, the border between Russia and Persia, Kotlyarevski attacked the Persians at Aslanduz on October 19 and defeated them, capturing the fortress later during the night. For this victory, Kotlyarevski was promoted to lieutenant general.

The Lenkoran Fortress, surrounded by swamps, protected by strong fortifications, and garrisoned by 4,000 Persians, was next. On December 26, Kotlyarevski arrived at Lenkoran. Lacking heavy artillery, the five-day bombardment was futile. With cannon ammunition running out and with reports of a strong approaching Persian relief force, Kotlyarevski made the decision to take the fortress by storm.

On the eve of assault Kotlyarevski ordered, “There will be no retreat. We must to take the fortress or all die…. Don’t listen for the recall signal, it will not come!” Looting was prohibited under penalty of death until the assault was over.

The assault began before dawn on December 31, 1812. The advancing Russian columns were met with withering fire. Particularly heavy casualties were among Russian officers, customarily leading from the front. When a colonel leading one of the columns fell, Kotlyarevski placed himself at the head of his men. A bullet pierced his leg, but the brave general began climbing an assault ladder. As he reached the top of the wall, two bullets struck him in the head and Kotlyarevski tumbled from the wall.

Seeing their beloved general fall, the enraged Russian soldiers carried the fortress by bayonet. No quarter was given and a majority of the Persian defenders were hunted down through the fortress. Miraculously, Kotlyarevski survived his grievous wounds.

The fall of Lenkoran decided the outcome of the Russo-Persian War, with Persia ceding large swaths of territory south of the Caucasus Mountains. Due to his wounds, Kotlyarevski resigned from the army, settling in Ukraine.

When the next war with Persia began in 1826, Czar Nicholas I offered Kotlyarevski command of the Russian forces in the Caucasus. Kotlyarevski declined, however, citing poor health. Kotlyarevski lived the remainder of his life in seclusion. He passed away in 1852.

Events in the Caucasus were overshadowed by Russia’s titanic struggle against Napoleon, and the name of Kotlyarevski is virtually unknown even in modern Russia. Nonetheless, the “Scourge of Caucasus” wrote a brilliant page in Russian military history.

Mikhail Skobelev

Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev was born on September 29, 1843, in the Peter-and-Paul Fortress, St. Petersburg, where his father was serving as a lieutenant and his grandfather was the commandant. Educated in Russia and France, young Skobelev entered military service at the age of 18 in 1861, commissioned directly into the most prestigious unit in the Russian Army, the Chevalier Guard Cavalry Regiment, where his father started his military career as well.

In 1864, by his own request, Lieutenant Skobelev transferred to a hussar regiment on active service, fighting against Polish rebels. He participated in several actions, earning a decoration for bravery. In 1866, Skobelev graduated from the General Staff Academy and was assigned to the General Staff. Besides bravery and showing an independent streak, the young officer demonstrated a talent for staff work and was periodically assigned to various staff positions.

Skobelev’s career took off in 1868 after his assignment to the Turkmenistan Military District in the so-called Russian Middle East (territories of modern-day Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, Tadzhikistan, Turkmenia, and Uzbekistan). Not all the local rulers, or khans, or some segments of the population submitted to the Russian rule, and the region was rife with constant raids, skirmishing, and looting.

The young officer distinguished himself as a skilled small-unit cavalry leader, conducting frequent reconnaissance forays and skirmishing. In 1873, Skobelev participated in the campaign against the Khiva Khanate, one of the last independent enclaves in the region. On one occasion, leading a detachment of cavalrymen, Skobelev attacked a much larger group of local horsemen, routing them. This action cost him seven lance and saber wounds.

In early 1875, Mikhail Skobelev returned to Turkmenistan, already a colonel, where a rebellion was flaring up in the former Kokand Khanate. Once again, Skobelev distinguished himself in numerous actions, almost always fighting severely outnumbered. For his accomplishments, 32-year-old Skobelev was promoted to major general and appointed as the military governor of the newly established Fergana District. The region was far from peaceful, however, and on several occasions Skobelev had to resort to brutal measures to bring the rebellious tribesmen to heel.

With the start of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, Maj. Gen. Skobelev was transferred to Bulgaria. Briefly serving as the chief of staff of a division commanded by his father, Dmitri Skobelev, Mikhail soon received an independent command. After distinguishing himself in capturing the strategic Shipka Pass over the Balkan Mountains and the town of Lovcha, Mikhail was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general, same as his father. The young general was immensely popular among Russian troops. Always in the thick of the action, the dashing Skobelev took to wearing a bright white uniform coat and riding a white horse. The Russian soldiers called him “The White General.”

Skobelev won everlasting fame during the siege of the town of Plevna. The town was well fortified and garrisoned by a strong Turkish force ably led by General Osman-Pasha. Turkish defenses consisted of a number of well-sited and mutually supporting redoubts with interlocking fields of fire. On July 17-18, 1877, without preparations, the Russians launched two assaults against the town and were soundly repulsed, suffering heavy casualties in the process.

On August 30, after four days of artillery bombardment, three Russian columns advanced on the town. Two columns, after capturing several minor outlying positions, bogged down in the face of withering Turkish fire. The third column initially met a similar fate until Skobelev personally led the reserves forward to support their wavering comrades.

Wearing a white uniform and mounted on a white charger, Skobelev presented a tempting target for Turkish riflemen. As he neared the southern redoubt, Skobelev’s horse was shot out from under him, and the general led his men forward on foot. Inspired by Skobelev’s leadership and enraged by their casualties, Russian soldiers broke into the southern redoubt. Those Turkish defenders who did not flee were mercilessly hunted down with bayonets.

In the morning, the Turks launched five furious counterattacks to retake the redoubt, each beaten back at great cost. Incredibly, the Russian command ordered Skobelev to abandon the redoubt. With a heavy heart, Skobelev and his men withdrew from the redoubt. “Napoleon was happy when one of his marshals could gain a half an hour for him,” said Skobelev. “I held on for 24 hours and they did not take advantage of it.” The town eventually surrendered in December after a four-month siege.

After the fall of Plevna, Skobelev led the advance cavalry detachment toward Constantinople. However, the Turkish government lost the will to fight. When the armistice was signed on January 31, 1878, Skobelev was less than 20 miles from Constantinople.

Skobelev returned to Russia, enjoying immense popularity and influence. His experiences in Romania and Bulgaria led him to become an outspoken proponent of Pan-Slavism, a movement aimed at unity of all Slavic people. During his postings after the war, he was increasingly concerned about the threat posed by the resurgent Germany. His rapid rise and his vocal criticism of the conduct of the last war, however, created jealousy and suspicion among some in the highest levels of government.

Skobelev died in Moscow on July 4, 1882, at the age of 39 under suspicious circumstances. Before arriving in Moscow, the general seemed brooding and troubled. He liquidated all of his assets and accumulated a large amount of cash. He was reputed to have given a packet of unknown documents to a friend. “I am afraid they will be stolen,” he told his friend. “I have been under suspicion for some time.” Skobelev had been openly critical of the policies of Czar Alexander II and after the czar was assassination in 1881, he earned the open enmity of the new czar, Alexander III.

Several days after his arrival in Moscow, Skobelev’s body was found in brothel.

Heart attack was declared as the official cause of death. Conspiracy theories abound, and his death remains a mystery.

“Soldiers generally win battles; generals get credit for them,” Napoleon Bonaparte said. Yet, the five commanders discussed here all deserved the credit they received. Each man was able to spot an opportunity, assess it, and act decisively. Whether faced with Teutonic knights, French grenadiers, or Asiatic tribesmen, they did their duty with unflinching bravery.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments