by Blaine Taylor

Had he—and not Emmanuel, the Marquis of Grouchy—been named a Marshal of France on April 1, 1815, General Count Jean Rapp might have helped the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte win the Battle of Waterloo. As it was, 10 days after that epic French debacle, Rapp won the last French victory of the Hundred Days against the Austrians at the small Battle of Le Souffel as commander of the frontier Army of the Upper Rhine. Thus, he checked Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince zu Schwarzenburg (1771-1820), and held onto the important city of Strasbourg in Alsace-Lorraine until Napoleon abdicated a second time and the Bourbons returned once more to Paris.

[text_ad]

Count Jean Rapp Statue Twice Removed By The Germans

Today, a statue of Jean Rapp, designed by sculptor Frederick Auguste Bartholdi, stands in his native Colmar. Emblazoned on its base is the inscription “My word is sacred.” Erected in 1840, it was removed in 1872 by Imperial German authorities after Alsace-Lorraine was taken from Republican France, then returned after the loss of World War I by Germany in 1918. In September 1940, Adolf Hitler had it removed yet again, but it was returned a second time in 1948 by the lst French Army after World War II witnessed the restoration of the two provinces yet again to France. It remains there today. Rapp’s name also appears on the Arch of Triumph in Paris, which is unusual since names of generals are not often included.

Noted Napoleonic scholar David G. Chandler lists Rapp among “a cluster of lesser lights” operating under the Emperor’s big trio of “right-hand men”: Berthier, Duroc, and Caulaincourt, adding (in his epic tome The Campaigns of Napoleon, 1966), “A handful of unattached generals was always held available in a cadre for special missions. There were also the official aides-de-camp (almost all of them full generals of the greatest distinction), headed by Mouton, Rapp, and Savary; these key personnel were expected to be equally capable of leading a charge, negotiating a treaty or cooking a chicken—in other words to perform any conceivable duty. Each had his own staff of aides and attendants.”

Much More Than Your Average Aide-de-Camp

Thus, in addition to being an Imperial aide-de-camp, Rapp was almost detailed by the Emperor in Russia in 1812 to lead an attack by the Imperial Guard against the Russian Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Mikhail Larionovich Golenishchev-Kutusov, before he thought better of it and changed his mind.

On the other hand, he and Marshal Joachim Murat ordered Rapp, on February 7, 1813, to hold Danzig with 30,000 men and 7,000 more in Thorn and Modlin, all in Poland, to fight off an expected Russian assault. In 1815 the restored Emperor thought enough of Rapp’s abilities not to take him to Belgium with his Army of the North and thus to Waterloo, but instead to hold France’s vital eastern frontier against an expected Austrian and Russian onslaught.

Jean Rapp was born on April 27, 1772 in Colmar, the son of an innkeeper, customs house official, and florist. Rapp had originally intended to become a Protestant minister, but in 1788 joined instead the 10th Regiment of the Chasseurs a Cheval (light cavalry). In Egypt he served as a lieutenant under General Desaix, became his aide, and distinguished himself at Sediman against the Turks. Wounded at the Battle of Samanhout, Rapp was promoted to colonel.

“A Hero For Each Victory Of the Empire”

Following the Battle of Marengo, he was promoted to General of Brigade in 1803, and two years later, following Austerlitz, to General of Division for his daring feat of leading a charge of Mameluke Egyptian cavalry of the Imperial Guard (which he had been ordered to form by Napoleon) against the Russian Imperial Guard and taking prisoner its commander, General Prince Nikolai Grigorievich Repnin-Volkonski. Later, a colored engraving would be commissioned by the Emperor entitled “A Hero for Each Victory of the Empire.” At the top left was the acknowledged hero of the Battle of Austerlitz, General Count Jean Rapp, an accolade he well deserves.

Indeed, it was during this epochal contest of the three Emperors—Napoleon I of France, Tsar Alexander I of Russia, and Kaiser Franz I of Austria—that Rapp and his intrepid horsemen thundered into the pages of military history and the annals of Napoleonic legend forever.

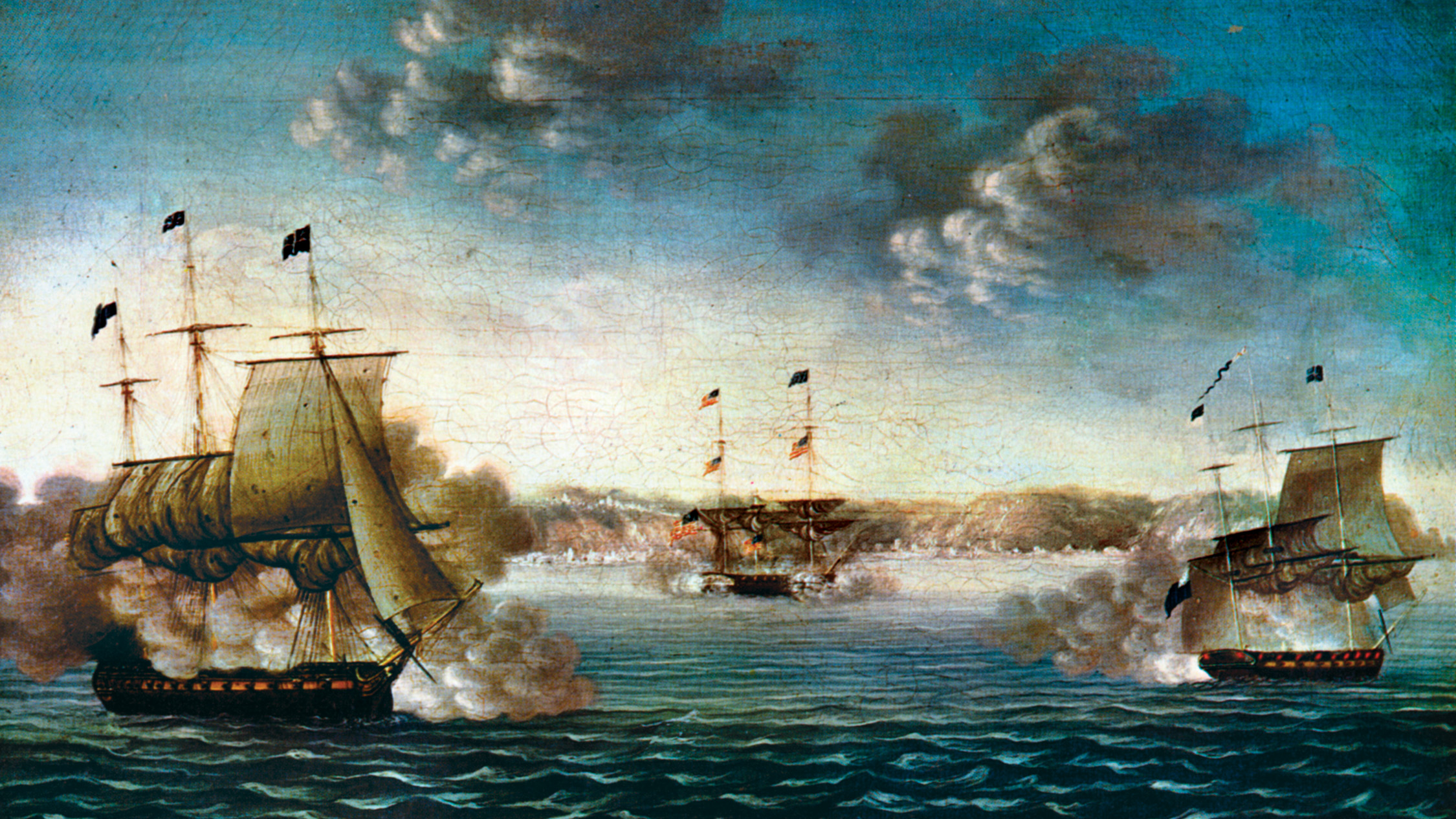

In the famous work Anatomy of Glory: Napoleon and His Guard, authors Henry Lachaoque and Anne S.K. Brown state, “The charge of the cavalry of the [French Imperial] Guard appears to have been ordered by Bessieres and carried out in two phases. The first, led by Col. Morland with two squadrons of chasseurs and supported by three of horse grenadiers under Marshal Bessieres, rescued the 4th Battalion and threw back the cuirassiers of the Russian Guard. Then the French were thrown back in turn by the Chevalier Guards whom Rapp put to flight in disorder with his last three squadrons and the Mamelukes.

A Firsthand Account of the Battle

“‘I took off at a gallop,’ wrote Rapp. ‘The enemy cavalry was slashing our troopers. A short distance in the rear we could see masses of foot [infantry] and horse [cavalry] waiting in reserve. Then the enemy let go and turned on me. Four pieces [of artillery] were brought up at a gallop, unlimbered, and set up in battery.

“‘I advanced in good order with the brave Colonel Morland on my left and General Dahlmann on my right. We charged the artillery and captured it. The cavalry stood firm awaiting our attack, then broke under the shock and fled in disorder. A squadron of grenadiers came to my support at the same moment as reserves arrived to support the Russian Guard. The shock was terrific. The infantry did not dare fire, since we were all jumbled together, fighting hand-to-hand.

“‘At last the intrepidity of our troops carried all obstacles. The Russians fled the field and disbanded. The guns, baggage and Prince Repnin were all in our hands. With my broken sabre and covered with blood, I went to give an account of the affair to the Emperor. A victory won by so few troops over the elite of the enemy inspired him with the idea for the picture painted by Gerard.’

“The chasseurs lost Colonel Morland, a captain, 11 non-commissioned officers and troopers killed, and 17 officers and 50 men wounded; 153 horses were put out of action. The horse grenadiers had only six officers wounded, but they lost 99 horses. By 1:30 pm, victory was assured.”

“A Remarkable Propensity For Collecting Injuries”

In March of 1806, Napoleon commissioned a series of paintings depicting the principal events of the campaign of 1805, assigning to Gerard the “Capture of the Imperial Russian Guards.” It meant to show Rapp presenting Prince Repnin, cannon, flags, and more than 800 captured noblemen of the Russian Guard to the Emperor at Austerlitz. It still hangs in the Hugh Bullock, Esq. Collection in New York.

In the Jena-Auerstadt campaign of 1806 against the Prussians, Rapp received the ninth of what would later total 25 wounds in his military life, leading even Napoleon to comment upon his “remarkable propensity for collecting injuries.” Rapp replied that it was no wonder because they were always fighting.

Rapp, indeed, was always in the very thick of combat. In his posthumously published Memoirs (London, 1823) he details how his left arm was broken fighting the Russians once more: “We experienced obstinate resistance on the part of the enemy. He attacked us: we charged with the bayonet; and our battalions drove him back on his own masses.

Falling Out of Napoleon’s Favor

“We remained masters of the field: It was covered with the bodies of the dead, and with bags that the Russians had thrown down in order to fly with the greater speed. The infantry was dislodged, and the cavalry now advanced. I went forward to meet them and drove them back, but the voltigeurs (skirmishers and grenadiers), who were dispersed about in the marshes, overwhelmed us with their (musket) balls: I had my left arm broken.”

Even Rapp added here, “I had been four times wounded in the first campaigns of the Army of the Rhine, under Custine, Pichegru, Moreau and Desaix; twice before the ruins of Memphis, and in Upper Egypt before the ruins of Thebes; at the Battle of Austerlitz and at Golymin. I also received four other wounds at Moscow.”

Rapp missed the 1809 Battle of Wagram after suffering three broken ribs and a dislocated shoulder in the overturning of a carriage three days before the battle.

He also fell out of favor with the Emperor for showing sympathy for Napoleon’s wife Josephine after the divorce and, when appointed Governor of Danzig (present-day Gdansk in Poland), for disagreeing with Emperor-ordered trade restrictions.

The Cold Russian Campaign

Rapp was back in the thick of it during the great Russian campaign of 1812-1813, however. At Borodino he led the 5th Division of I Corps after its commander, Compans, was wounded. During the battle, Rapp was wounded four times.

Like everyone else in the Grande Armee during the retreat from Moscow, Rapp suffered terribly. He later wrote: “The cold was so intense that, when I arrived at Vilna, I had my nose, one of my ears, and two fingers frozen.” Nevertheless, he was ordered to command the defense of Danzig to act as a bulwark against Russian expansion west. He lamented the garrison soldiers, drawn from no less than seven countries.

“I had 35,000 …,” Rapp later wrote, “out of which there were not eight or ten thousand fighting men; even these were nearly all recruits who had neither experience nor discipline.” Nevertheless, he managed to defeat the first Allied assault on the city, suffering six hundred losses. “The enemy had suffered more; 2,000 of their troops lay on the dust, we had between 11 to 12,000 prisoners in our hands, and one piece of artillery. This day was one of the most glorious of the siege, a fresh example of what courage and discipline may affect. Under the walls of Danzig, as at the passage of the Beresina, worn out by want or by disease, we were still the same. We appeared on the field of battle with the same ascendancy, the same superiority.”

Defeated By the Russians And Imprisoned

There was a second part of the siege, however, which included an epidemic that killed 6,000 and hospitalized an additional 18,000. Food was scarce. So was pay for the troops. Rapp demanded money from Danzig’s citizens, who became indignant.

Meanwhile, the fighting was furious. Rapp recalled, “It is no longer a battle—it is slaughter, it is carnage, all perish at the point of the bayonet, or only owe their lives to the mercy of the conquerors. While our soldiers are giving themselves up to the fire of their courage, a cloud of Cossacks rush on them, and threaten to cut them to pieces.…” In addition, the Allied fleet threw shot and shell into the besieged city.

After a year of this, Rapp was forced to surrender the city and was imprisoned in Kiev. Upon his parole, and hearing that the Emperor had abdicated, he placed his sword at the service of the restored Bourbon dynasty.

An Emotional Last Meeting With Emperor Napoleon

Then, following the Emperor’s return, there was a stormy meeting between the two soldiers and friends at the start of the fabled Hundred Days.

“Did you really intend to fight against me?” Napoleon asked.

“Yes, Sire,” Rapp replied, from his Memoirs.

“The Devil!” the Emperor retorted. “I was very well aware that you were before me. If an engagement had taken place, I would have sought you out on the field of battle … Would you have dared to fire at me?” he asked Rapp.

“Undoubtedly, my duty …” Rapp replied.

Napoleon rejoined: “This is going too far, but the soldiers would not have obeyed you! … If you had fired a single shot, your peasants of Alsace would have stoned you … At the death of Desaix, you were nothing but a soldier—I made a man of you!.… I shall never forget your conduct in the retreat from Moscow … At your siege of Danzig, you did more than impossibilities. …”

At this, the Emperor broke down, held Rapp to him for two minutes, pulled the ends of his mustache as a show of affection, and appointed him to the final Imperial command of the Army of the Rhine. “Come, come, a hero of Egypt and Austerlitz can never forsake me!” It was to be their final meeting.

News Of The Waterloo Defeat Reaches Troops

General Count Rapp went to take up his newest posting: “We scarcely reckoned 15,000 infantry, which were divided into three divisions, under the orders of Generals Rottembourg, Albert and Grandjean; 2,000 horse under Count Merlin composed all our cavalry. From Weissemburg as far as Huninguen on one side and to Belgium on the other, the frontiers were completely unprotected.”

Then came the news of the Emperor’s final loss at Waterloo, but Rapp—like the Emperor—initially determined to fight on. He was to be opposed by an Allied army of 60,000 men: Russians, Austrians, Bavarians, Wurtemburgers, Badeners, and others, and they attacked his advanced posts on June 24, 1815, six days after Waterloo.

Rapp had taken care to conceal the news of the French defeat from his men, but now it reached them: “Fatal projects entered the minds even of those who were least carried away by passion,” Rapp later wrote. “Excited by malevolence, some wished to return to their homes; others proposed to throw themselves as partisans into the Vosges [Mountains].”

One regiment even made known its intentions of leaving the army, hitched up its artillery, and was preparing to leave for the mountains. Rapp recalled, “The cannon were already harnessed … I rushed to the spot. I took in my hand the eagle of the rebels and, placing myself in the midst of them, cried, ‘Soldiers! I learn that it is proposed among you to desert us. In an hour’s time, we shall fight. Do you wish the Austrians to think that you have fled from the field of honor?’

General’s Impassioned Words Touch Soldiers

“‘Let the brave swear never to quit their eagles or their commander-in-chief. I grant permission to the cowards to depart!’ At these words, all exclaimed, ‘Long live Rapp! Long live our general!’ Everyone swore to die by his standard, and tranquility was restored.” Like his Emperor at the Golfe Juan earlier that year, Rapp well knew the value of a dramatic gesture among such rough-hewn soldiers.

Thus it was that General Count Jean Rapp was now poised to win the last French victory of the First Empire. Of the battle, he recalled, “I made a rapid charge: I routed the first line, penetrated the second, and overthrew everything that offered me any resistance. We made a dreadful slaughter of the Austrian and Wurtemburg cavalry.… the field of battle is covered with the slain. … He had from 1,500-2,000 men killed, and a still more considerable number wounded.”

The war at length ended after the Second Abdication of the Emperor—but it was still not over for Rapp, who faced a mutiny of his to-be-disbanded army on September 2, 1815. The officers, NCOs, and soldiers asserted they would not return home without their promised pay and with their arms, ammunition, and baggage intact as well.

Unpaid Soldiers Threaten Insurrection

Rapp found himself faced with an assembled body of five hundred NCOs. He found fixed bayonets, loaded muskets, and rebel cannon ranged against him. An account of the incident reported: “He ran to the cannoneer who was holding the match. ‘Well! What would you do, wretched man? Do you wish to kill me? Fire, then, for here I am at the mouth of your cannon!’ Rapp challenged the startled soldier.

“‘Ah, General, I was at the siege of Danzig with you. I would give you my life, but my comrades will be paid, and I am obliged to do as they do.’”

Rapp insisted later that he had no money to pay them, adding, “You have heard me: Begone! I am ashamed to converse with rebels!” He was called a traitor, and threatened with assassination, but stood his ground. When the paymasters arrived, the troops were duly paid and the Army of the Rhine peaceably disbanded. Like the Emperor twice before him, he had prevented civil war by his courage.

Rapp returned to Paris in 1818, having won decorations from both the Empire and the Bourbon monarchy. He was made a member of the House of Peers and died of cancer in 1821—the same year as his former Emperor on the far-off Island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic off the coast of Africa.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments