By Al Hemingway

Lieutenant General Lewis Walt was not a happy man. The burly III Marine Amphibious Force commander had just been ordered by Commanding General William C. Westmoreland to assist in the construction of a barrier to stem the flow of men and materiel coming into South Vietnam from the north. To professional military men like Walt, the concept was a foolish one. Washington, as usual, had other ideas. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara had been convinced by Harvard Law School Professor Roger Fisher that a “conventional mine and wire barrier to be backed up by monitoring troops” was the key to halting the estimated 15 enemy battalions crossing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) into the south. The proposed barrier was to run from the South China Sea westward across the northern part of South Vietnam, all the way to Laos and eventually into Thailand.

The Strong Point Obstacle System

From the outset, McNamara met resistance to his plan. Navy Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp, commander-in-chief of all American forces in the Pacific, objected vehemently. He pointed out that the scheme would put a tremendous strain on the logistical community. The gigantic construction endeavor and massive amount of manpower required to maintain and protect it weren’t worth the effort, in Grant’s opinion. Walt and his Marines could not have agreed more. “To sum it up,” said one Marine officer, “we’re not enthusiastic over any barrier defense approach to the infiltration problem. We believe that a mobile defense by an adequate force would be a more flexible and economical approach to the problem.” Another Marine put it even more bluntly: “With these bastards, you’d have to build the zone all the way to India, and it would take the whole Marine Corps and half the Army to guard it. Even then they’d probably burrow under it.”

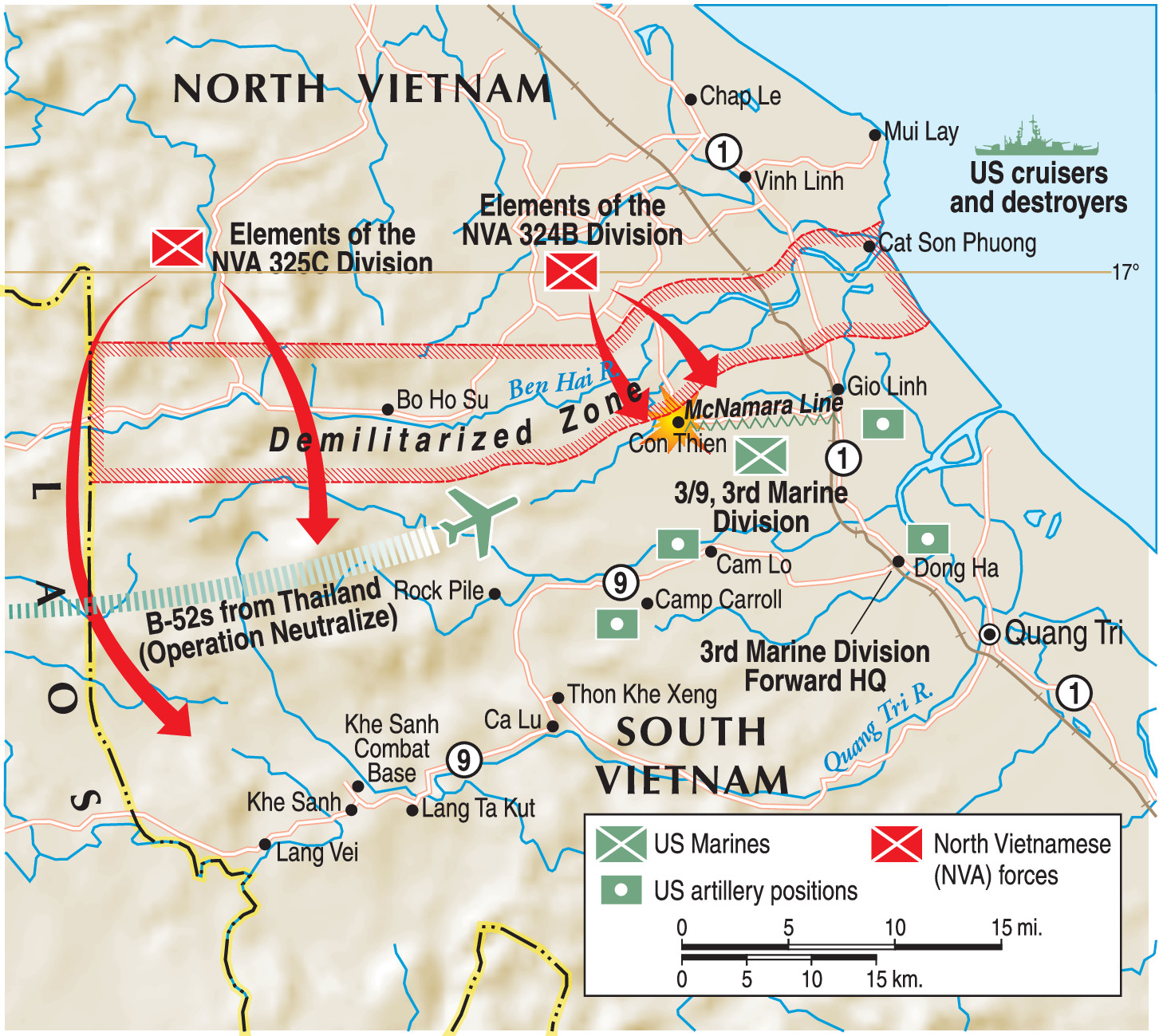

Still, McNamara persisted. In September 1966, the JASON Group, a self-described “university think tank,” presented their new, improved barrier design. This time they added air support to the mix. Determined to implement the plan, McNamara chose Army Lt. Gen. Alfred D. Starbird to lead Task Force 728. He directed him to “provide an infiltration interdiction system to stop (or at a minimum substantially reduce) the flow of men and supplies from North to South Vietnam.” Westmoreland also wanted the barrier put in place. Instead of an actual fence, a path would be hewn out of the jungle just below the DMZ and anchored by strongpoints. Phase one of the so-called Strong Point Obstacle System (SPOS) would extend from Gio Linh, on South Vietnam’s east coast, to Con Thien, an abandoned French fort located near the DMZ.

In April 1967, the Marine 11th Engineer Battalion quickly cleared a 200-meter swath of land between the two bases dubbed the “Trace.” Those who participated in its construction called it a “firebreak.” Others referred to it more pessimistically as a “death strip.” The SPOS plan called for six eventual strongpoints. Alpha 1, near the South China Sea, would be occupied by ARVN (South Vietnamese) soldiers. Alpha 2 would be located at Gio Linh. Con Thien would become Alpha 4. (Alphas 3, 5, and 6 would not come along until later.) These strongpoints would be backed by fire-support bases located several kilometers to the south. The Marines were to build one strongpoint halfway between Cam Lo and Con Thien. A dirt road identified on the maps as Route 561 would become the main supply route between them. The four Marine positions at Con Thien, Gio Linh, Dong Ha, and Cam Lo formed a rough square. Soon, “Leatherneck Square” would assume a permanent place in Marine Corps lore.

Con Thien: Hill of Angels

Of all the strongpoints along the DMZ, the most important was Con Thien. It was a low hill mass, the highest being just 158 meters, that nevertheless commanded an unobstructed view for miles around. The isolated Marine firebase was a mere two miles from the DMZ. In Vietnamese, “Con Thien” loosely translates as “a small mountain with heavenly beings.” It was also called the Hill of Angels. Visitors to Con Thien could look back at the vast logistical complex of Dong Ha and know instantly why the Marines had to hold the hill. “If the enemy occupied it he would be looking down our throats,” warned Colonel Richard B. Smith, commanding officer of the 9th Marines.

To defend the remote outpost and keep a watchful eye on the enemy’s activities in and around the DMZ, infantry battalions from the 3rd Marine Division rotated into Con Thien on a regular basis. Soon, the Leathernecks began referring to the grueling duty as their “time in the barrel.” Other, more grisly names would soon enter the lexicon— “meat grinder” and “hellhole.” As casualties mounted, infantrymen began calling the DMZ the “Dead Marine Zone.”

The NVA’s First Assault

All the activity around the DMZ did not escape the watchful eye of the North Vietnamese. Until then, the Communists had enjoyed a sanctuary in the southern half of the region. Now the Americans were getting too close for comfort, and Hanoi intended to do something about it. In the early morning hours of May 8, 1967, North Vietnamese sappers from the 4th and 6th Battalions, 812 NVA Regiment crept toward the northeast and southeast sections of the perimeter at Con Thien. The area was thought to be manned by ARVN troops and a small contingent of Chinese Nungs from the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG). This time, however, the North Vietnamese had erred. Unbeknownst to them, the ARVN soldiers had departed and the perimeter was now manned by Companies A and D of the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, along with a platoon of engineers and several tanks from Company A, 3rd Tank Battalion, 3rd Marine Division.

Just before 3 am a flare lit up the night sky, the signal for the NVA attack to commence. Enemy guns showered Con Thien with shells and mortars as sappers rushed the razor-sharp concertina wire. Blasting gaps in the line with bangalore torpedoes, the scantily clad shock troops began tossing satchel charges into all the bunker openings. About 4 am the main NVA force charged the perimeter. The Nungs were forced to retreat and linked up with a small force of U.S. Navy Seabees to hold off the hordes of enemy troops. In addition to their explosive devices, the enemy used flamethrowers to burn alive any unfortunate occupants remaining in the bunkers—the first reported use of flamethrowers by the Communists since the war began.

Despite the suddenness of the assault, the Leathernecks fought back heroically. Sergeant David Danner was struck by white-hot shrapnel when an NVA gunner scored a direct hit on his tank with a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. Ignoring his wounds, Danner managed to carry the remainder of his crew members to the battalion aid station. He then returned to his tank and commandeered its .30-caliber machine gun to help repulse the attackers. Ignoring heavy enemy fire, he rushed to assist a wounded Marine, carrying him to safety. Danner would ultimately be awarded a Navy Cross for his heroic actions that night.

Corporal Charles D. Thatcher was another Marine who performed heroic service during the attack. Thatcher was peppered by shrapnel in his back and neck, but continued to give a wounded comrade medical aid. He then climbed back into his tank and fired its machine gun until his ammunition was expended, killing an NVA soldier attempting to launch an RPG round at another tank. For his bravery, Thatcher would also receive a Navy Cross.

As the NVA moved toward the airstrip, the 1st Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion accompanied by an Army M-42 Duster and several Marine amphibious tractors, or amtracs, struck at the enemy. One of the amtracs was hit by an RPG round, turning the vehicle into a flaming coffin. As it burned, the terrifying screams of those trapped inside could be heard. Soon, all three vehicles were destroyed by enemy fire. From out of nowhere, Lance Cpl. Michael P. Finley fired several rounds from his M-79 grenade launcher. Both 40mm grenades landed on an NVA machine-gun emplacement. Finley was struck by enemy gunfire, but managed to dash to another Marine’s aid. He was shot and killed attempting to reach his wounded squad leader. Finley was posthumously awarded a Navy Cross for his service.

By dawn the fighting had subsided and the NVA had been beaten back. The enemy had sustained nearly 200 killed; only eight were captured. The Marines suffered 44 killed and 110 wounded. The battle to seize Con Thien taught Hanoi valuable lessons. General Vo Nguyen Giap, commander of the Communist forces, realized that he could not effectively confront the Marines openly in such clashes because of their devastating firepower. Instead, he opted to play a hit-and-run game, staging ambushes and hammering Con Thien with artillery and mortar barrages to keep the Marines off balance.

Operation Hickory

The May 8 attack finally convinced Washington that something had to be done about the NVA positioned in the southern portion of the DMZ. Westmoreland instructed the Marines to flush the Communists from their hideouts in the region. The Leathernecks conceived a three-pronged operation to thwart the NVA. The 3rd Marine Division’s part was named Operation Hickory; Lam Son 54 was the codename for the ARVN part of the plan. Marines from Special Landing Forces (SLF) Alpha and Bravo, situated on vessels in the South China Sea, also participated. Beau Charger was the name for SLF Alpha, Belt Tight for Bravo.

On May 18, Operation Hickory commenced with a huge artillery bombardment. Nearly 700 rounds of 105mm and 155mm shells pounded suspected enemy fortifications near the hamlet of Phu An. This region was considered vital to the Marines because of its close proximity to the Communists’ main staging routes. Immediately following the shelling, fighter jets delivered 750- and 1,000-pound bombs and saturated the area with napalm. Elements from the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines quickly moved in and secured the area, counting nearly 30 enemy dead and 75 shattered bunkers.

Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion, 26th Marines advanced into the southern half of the DMZ with the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines, covering their right flank. Before the morning was over, the Leathernecks found themselves in a fierce firefight with NVA regulars shooting from well-concealed fighting holes. Corporal Robert Moffit of Company G delivered a heavy volume of rifle fire at a bunker complex concealed in a hedgerow, then advanced on a trench line and killed several enemy soldiers. The next day Company G was involved in another firefight. Once again, the fearless Moffit crept toward a machine-gun nest and tossed grenades into it to silence the weapon. He would live to receive a Navy Cross.

By late afternoon, dozens of 82mm mortar rounds had fallen in the headquarters area. The ensuing barrage wounded nearly 20 Marines, including the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Charles R. Figard. While the Leathernecks were heavily engaged, Operation Lam Son 54 began with two battalions of the 1st ARVN Division moving toward the Ben Hai River in the DMZ and advancing southward. While this maneuver was transpiring, three ARVN airborne battalions began a sweep on the western flank. The following day, May 19, the ARVN units encountered the 31st and 812th NVA Regiments. The South Vietnamese troops fought well, killing 342 enemy soldiers, capturing another 30, and capturing 51 weapons.

A Hard Fight for Beau Charger

While Lam Son 54 was enjoying some success, the Beau Charger part of the operation was not. Right from the outset, the Marines were in trouble. Lt. Col. Edward Kirby’s HMM-263 (Helicopter Marine Medium) ran into a vicious crossfire as his UH-34 Sea Horse helicopters tried to land the lead assault group from Company A, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marine, at Landing Zone Goose. Flying the lead chopper, Kirby ran into a hail of automatic-weapons fire as he hovered less than 50 feet from the ground to dislodge the infantrymen. The Communist gunfire disabled the helicopter’s radio and wounded most of the crew, along with three riflemen from Company A. Another Marine was killed instantly and fell from the chopper. Kirby managed to maneuver out of the precarious situation while the wounded door gunner kept up a steady stream of machine-gun fire. Kirby said later that the return fire “saved our bacon.”

Kirby flew his badly damaged chopper back to the USS Okinawa and immediately informed SLF commander Colonel James A. Gallo, Jr., of the desperate situation at LZ Goose. Gallo quickly canceled all flights and redirected them to LZ Owl, 800 meters south of Goose. This, unfortunately, did not help those Marines who already had landed at Goose. The enemy struck the perimeter of 2nd Lt. Dwight G. Faylor’s 2nd Platoon, which was thinly spread over an 800-yard area. The enemy moved so close to the Leathernecks’ lines that naval gunfire could not be delivered to support them.

By 11:00 am, relief forces began to reach the surrounded infantrymen, but the NVA chose to stay and fight instead of retreating. Company B, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, supported by several M-48 tanks, attacked a trench line holding numerous enemy soldiers. Soon, the Marines were entangled in hand-to-hand combat with the tenacious enemy. Corporal Russell F. Keck of Company A instructed his M-60 machine-gun squad to pour fire at the NVA trench line. As Communist mortars began to fall on their position, Keck ordered his team to relocate the weapon while he remained behind to provide covering fire for the rest of the company. He was killed while doing so and was posthumously awarded a Navy Cross. Nearly a dozen jets screeched overhead, dropping their ordnance and napalm. Companies A and B, supported by the tanks, overran the Communist trench line. In all, the Marines found 67 enemy bodies strewn over the area.

By the end of May, Operations Hickory, Lam Son 54, Beau Charger, and Belt Tight were finished. The invasion of the southern half of the DMZ netted 789 enemy killed and another 37 captured, along with 187 various weapons. The Marines, for their part, sustained 142 dead and 896 wounded.

Operation Buffalo

Although it had failed to destroy Con Thien, Hanoi had no plans of easing up on the firebase. Additional thrusts at the old fort were being planned, using long-range artillery pieces to harass the Marines. Realizing that the NVA were not going to go away, Marine strategists developed Operation Buffalo to strike at the enemy along the DMZ. Operation Buffalo kicked off on July 2 with Companies A and B, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines sweeping north-northeast of Con Thien. Two companies, unfortunately, were not enough to cover the large area. As Colonel George E. Jerue, commanding officer of the 9th Marines, pointed out, “The TAOR (Tactical Area of Responsibility) assigned to the 9th Marine Regiment was so large that the regiment could not enjoy the advantage of patrolling any particular sector on a continuing basis. As a result, an area would be swept for a few days and then it would be another week or so before the area would be swept again. Consequently, it became evident that the NVA, realizing this limitation, would move back into an area as soon as the sweep was concluded.”

This time, however, the NVA had no intentions of moving back. They had set up a cleverly concealed ambush and waited for the Marines’ arrival. The 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, given the ghoulish nickname the “Walking Dead,” would soon encounter its toughest assignment to date. Captain Sterling K. Coates’s Company B and Captain Albert C. Slater’s Company A moved north of the Trace to commence their sweep of the area. The Leathernecks endured the grueling heat and humidity as they pressed forward on Route 561. With the 3rd Platoon in front, followed by the command group, Company B began to encounter sporadic sniper fire. Suddenly, the air was filled with enemy gunfire. Coates’s men were struck from all sides as the Communists, hidden among waist-high hedgerows, hammered the Marines with automatic-weapons fire and mortars. The NVA employed flamethrowers, igniting the hedgerows and forcing the riflemen to flee the burning deathtrap. As they emerged into the open, the enemy slaughtered them.

The 2nd Platoon tried to reach the besieged 3rd Platoon, but was driven back. Soon, they were also cut off and found themselves fighting for their lives. Enemy artillery and mortar fire scored a direct hit on the command group, killing Coates, the radio operator, two platoon commanders, and the artillery forward observer. Hearing the loud crack of the gunfire, Staff Sergeant Leon R. Burns, 1st Platoon commander, attempted to reach the other two platoons, but NVA troops swarmed against the platoon’s flanks. Burns quickly radioed for air support. “I asked for napalm as close as 50 yards from us,” he recalled later. “Some of it came in only 20 yards away, but I’m not complaining.”

Listening to the radio traffic at Con Thien, Lt. Col. Richard J. “Spike” Schening, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines commander, wasted no time in ordering Company C into the battle. It was now evident that Company B had run into at least two NVA battalions. Captain Henry J.M. Radcliffe led a platoon from Company D, augmented by four M-48 tanks, to the scene. Meanwhile, Slater was running into difficulty linking up with the besieged Company B due to heavy enemy fire, although one platoon did manage to break through and join Radcliffe’s relief force.

As the small relief column made its way down 561 and moved northward, the NVA began peppering the Marines with small-arms fire. Helicopter gunships worked over the area, and 90mm rounds from the tanks scattered the enemy troops. Company C began choppering in, and Radcliffe told his rescue team to secure the LZ. Charlie Company set out to relieve Company B, but was met with Communist artillery fire that wounded 11 Marines. As they moved forward, Radcliffe found the remnants of Burns’s platoon—all that remained of Coates’s company. Radcliffe was stunned at the sight of so many lifeless bodies along the road. First Lt. Gatlin J. Howell, who had commanded the platoon for eight months before being reassigned, was also rendered speechless, but together with Corporal Charles A. Thompson of Company D, he helped to evacuate at least 25 Marines.

As the Marines made their way back to Con Thien, Major Darrell C. Danielson, the battalion executive officer, met the dazed survivors. Some of the less seriously wounded were put on trucks, while others were loaded on CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters. Even as the wounded were carefully placed about the choppers and vehicles, Communist gunners targeted Con Thien and Gio Linh with over a thousand rounds of heavy artillery. Slater’s Company A was also in dire straits, with enemy soldiers moving to within 50 meters of their lines. Air and artillery strikes, and the arrival of Company K, 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines, forced the NVA to withdraw. Alpha’s men gave their relief an emotional welcome. They knew that they would not have survived the night—the NVA would have overrun them and coldly executed them where they lay.

“I’d Hate to Tell You”

On July 4, while people back in the United States was celebrating Independence Day with fireworks and picnics, the Marines from the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines and the 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines moved back to the area that was the scene of so much death. The fighting increased in intensity and by nightfall, the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines from SLF Bravo was helicoptered in to reinforce the battalions.

The next day, aerial observers spotted NVA troops crossing the Ben Hai River. Climbing a tree to observe any enemy movement, Captain Burrell H. Landes, commanding officer of Company B, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, received word that a large Communist force was heading in his direction. Landes inquired about the size of the NVA unit. The aerial observer radioed back: “I’d hate to tell you.” As the 400-man NVA battalion, part of the elite 90th NVA Regiment, approached the Marine lines, nearly 600 130mm and 152mm rounds impacted near the Marines.

This time, however, the Leathernecks had a surprise for them. Captain Slater, whose Company A, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines had endured the nightmare of July 2, had been attached to the 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines and was waiting for them. “When the point of the enemy column was brought under fire, the NVA alerted their unit with a bugle call,” Slater said. “Their initial reaction was one of confusion and they scattered, some of them toward Marine lines. They quickly organized and probed at every flank of the 360-degree perimeter. Concealed prepared positions and fire discipline never allowed the NVA to determine what size unit they were dealing with. When the enemy formed and attacked, heavy accurate artillery was walked to within 75 meters of the perimeter. The few NVA that penetrated the perimeter were killed and all lines held.”

The battle was a brutal one. NVA sappers got near enough to toss satchel charges and blocks of TNT at the Marines. When he observed several Chicom grenades land near him, Lance Corporal James L. Stuckey quickly picked up each one and began flinging them back. One of the projectiles went off, severing Stuckey’s hand, but he remained with his squad throughout the battle. For his actions that night, Stuckey would be presented a Navy Cross.

Operation Buffalo ended on July 14. Nearly 1,300 NVA were reported killed; only two were captured. The Marines lost 159 killed and 345 wounded. “The most savage aspect was the heavy employment of supporting arms by both sides,” noted the official Marine Corps history of the operation. “Of the known enemy killed, more than 500 came from air, artillery, and naval gunfire. In addition, supporting arms destroyed 164 enemy bunkers and 15 artillery and rocket positions, and caused 46 secondary explosions. To accomplish this, Marine aviation used 1,066 tons of ordnance, Marine and Army artillery consumed more than 40,000 rounds, and ships of the U.S. Seventh Fleet fired 1,500 rounds from their 5- and 8-inch naval guns. On the other hand, enemy artillery accounted for half of the Marine casualties during the operation and posed a constant threat to Marine logistical support installations.”

Operation Kingfisher

Throughout the summer months and into the fall, the enemy kept up the pressure on Con Thien. Hanoi had plans to make the Marines’ stay along the DMZ, especially at the Hill of Angels, as miserable as possible. Their heavy artillery was to play a major part in the plan. In July 1967, the Marines launched Operation Kingfisher to once again strike at NVA positions near the DMZ. On September 4, Captain Richard K. Young’s Company I, 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines ran into an NVA unit about 1,500 meters from Con Thien. Company M, 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines moved on the left flank of Company I and overran the enemy force. A few days later, riflemen from the 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines fought what seemed to be the entire 812th NVA Regiment. For several bloody hours, the infantryman clashed with the enemy.

Sergeant David Brown of Company L, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines was everywhere on the battlefield. The physically and mentally tough Tennessean kept shouting encouragement to his men as he moved up and down the line. Captain Richard D. Camp, Lima Company’s leader, recalled Brown’s heroics that day: “He was just standing there, cool as you please, in the offhand position, with his M-16 tucked into his shoulder, shooting at NVA soldiers who were making their way up the trail. At that moment, the leading NVA were no more than thirty feet away from him. He was shooting them, one right after the other. By the time I looked up, he must have laid out about six or eight of them, all in a nice little pile.”

The firefight lasted into the night, with American fighter planes dropping napalm as close as possible to the perimeter. NVA gunners, in turn, unleashed numerous RPG rounds, striking several tanks and causing their ammunition to detonate. All through the night, the sounds of ‘50-caliber rounds “cooking off” permeated the air. At dawn, the NVA withdrew and the Marines counted 140 enemy soldiers scattered around their perimeter. The Leathernecks had suffered 34 killed and 192 wounded.

A Dismal Failure

Throughout September, the occupants of Con Thien endured heavy shelling from NVA artillery. From across the Ben Hai River that separated North from South Vietnam, NVA artillery targeted the Marines bases dotting the DMZ, especially Con Thien. “Almost daily we would receive at least 200 rounds of incoming,” recalled PFC Jack Hartzel of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines. “The constant pounding every day could make you go nuts. You would sit there on the edge, wondering if the next round that came in would have your name on it. I remember lying there at night trying to sleep, but sleep was impossible. I was too nervous. I remember I could hear the enemy rounds when they were taking off in the distance. We could actually hear them taking off. We were that close!”

Con Thien was subjected to some of the heaviest shelling of the war. Communist gunners would lob mortar and artillery rounds at the base, then quickly move their weapons before the Marines could locate them. Between September 19-27, an incredible 3,077 shells battered the Marine positions. September 25 was the worst day—some 1,200 rounds crashed into the fire base. “The thing about September 25th that really sticks in my mind,” said Hartzel, “is a Marine sitting in a pool of blood, his legs blown off. He was numb from morphine and in shock from loss of blood. He was smoking a cigarette very calmly as if nothing had happened.” Of the 45 men who reported for duty from Hartzel’s platoon, only 12 walked out unscathed.

By the end of 1967, the imminent threat toward Con Thien had finally subsided. Attention would soon be focused on the besieged Marine base at Khe Sanh, and Con Thien quickly faded from memory. The barrier and SPOS plan that Secretary of Defense McNamara had envisioned would prove to be a dismal failure. Those who survived the hell of Con Thien would never forget their “time in the barrel.” The torrential monsoon rains that transformed the red dirt around the base into a quagmire, the constant shelling that could leave one totally demoralized and the threat of being overrun and killed would be indelibly etched in their minds for all time. As for the hundreds of Marines and U.S. Navy corpsmen who died defending that seemingly worthless piece of land—their spirits would remain forever on the Hill of Angels.

Just a question. Was B-52’s used at all on the NVA artillery?

B52s were over our heads every 90 minutes, Arclight sorties. The gun were mounted on rails and ran back into caves. We bombed the tracks and they would rebuild them overnight. I was with Mike Company 3/9 from August 8, 1967 until December 1967. I was wounded at Con Thien in September 22,1967 and medevaced to the USS Sanctuary. No way to describe that nightmare.

My father was in the 1st Marines in this battle. He is currently in hospice. I’d love to connect with anyone who’d like to talk about this experience. I will find out more details from him as far as dates, etc. His name is Ed Mangum and he’s from Grand Rapids, MI. Please feel free to contact me. Thank you.

Elizabeth, God Bless you. I was with Delta Company (we called it Dying Delta), 1st Btn, 9th Marines, and was wounded just 2 days before the start of Buffalo. We were sweeping north of Con Thien — I’m pretty sure we were in the Z — when I got shot (not serious) while trading point with a crazy South Boston Irishman named Ray Kelly. He saved my bacon that day, and I was back on Con Thien on light duty when my platoon (2nd) was attached to go out and retrieve bodies, destroy/retrieve equipment, etc. I had been a radio man for 6-8 months, so I heard the whole Bravo Co. fiasco as it happened. Sad.

You can contact me at my email addr, aanderso.cw@verizon.net, and please use “CON THIEN” in the subject as I get so many emails. God bless, and tell your Dad a fellow Marine from Con Thien said hello, Semper Fi, and I hope to see you in Heaven soon. BTW, IF your dad is not saved, please take him to church so he can hear the Word and be called by the spirit, as we are deep in the End Times, and Christ is returning very soon!

Andy, Doc K here…1/9 Delta Company 3rd Platoon.6/68-5/69..sounds like I followed a bit after your tenure. Remember joining 1/9 when they were near Cam Lo along the river and then moving out to sweep through Con Thien and Khe Sanh areas with tanks on my first operation with them. Served through operations Kentucky, Scotland, Dawson River, Dawson River West and beginning of Dewey Canyon before being relieved from the field and headed to 3rd med battalion in Quang Tri working in the ICU. Lots of memories of LZ Stud (later Vandegrift Combat Base), Rockpile, multiple combat bases, miserable days-nights during monsoon rains and getting stranded inside the DMZ (Johnson signed special order) for nearly 2 weeks with long rats for 5 days! Thanks for your service brother and great advice to Elizabeth. Semper Fi and Psalm 46:1

it was the same as you describe when I hauled 105 mm ammo to Con Thien in 68-69. The intensity was much less.

I was with Dying Delta, 1/9 from March 1967 to rotation on 30Dec67, and was wounded and medivacked while sweeping north of Con Thien 30Jun67. That turned out to be the end of Kingfisher/start of Operation Buffalo. There is an excellent book on Buffalo, Operation Buffalo: The Marine Fight for the DMZ by Keith William Nolan.

Semper Fi to all my comrades in arms who served in the pickle barrel.

Absolutely. From Con Thien, we saw many secondary explosions caused by the “Arc Lights”. I’ve met several B-52 crew and support personnel since then, and thanked them every one, and let them know what that meant to us on the Hill. Without Arc Lights, we’d almost surely have been overrun several times.

Was at Con Thien Sept and Oct 67 with Mike Co., 3dBn, 4thMarines. Truly it was a hell hole and a meat grinder. Left there late Oct 67 and headed for home. Spent 20 months in country all with Kilo 3/4 and Mike 3/4.

I Was A Medevac Corpsman With HMM-361, Out Of MAG-16 FWD, Dong-Ha 1967

Flew For Con-Thien, Khe-Sahn, Gio-Lyn, Cau-lo, Camp Carroll.,

SEMPER FI COMRADES ❤️??

Sean Barry HM2 MAG-16FWD Dong-Ha

E-mail: musicstr47@gmail.com

Does anyone remember a marine named Ken Sewatsky, (from NJ) operated an ENTOS? Gary Schubert (from West Virginia) [KIA] ? Con Thein, Khe San, Dong Ha? Ken was My ex husband, former marine , asking for my children. GOD BLESS ALL OF OUR WARRIORS, THANK YOU?? SEMPER FI ??

Semper Fi, Doc, and God bless you all. You guys had more courage than all the rest of us put together…which is saying something.

You left out one of the biggest and most costly battles in US Marine Corps History. The battle was part of Operation Kingfisher, it occurred from July 28-30, 1967. It originated and was conducted out of Con Thien into the DMZ.

As the son of Veteran that served here during this time. The accuracy of this information is vitally important to RESPECT & HONOR these Men that fought here and to provide accurate information for all to be educated about.

Spent Nov. 1967 to Dec. 1967 at Con Thien, with Charlie company 1/1. I was the Radioman for the Arty FO team. Got my second Purple Heart there, on OP 3. on Dec 5. The monsoon mud was over a foot deep, and just walking was a chore. The cold was the worst. MISERABLE is the only word to describe this Hell on earth. During TET, Charlie 1/1 was in Hue City. Operation Pegasus in April ”68 was my last operation. 1/1 and the 1st Air Cav broke the seige at Khe Sahn. Also took part in Operation Medina in OCT 67. My first operation was Operation Union, in April 67 , in the Que Son Valley. One bad Operation after another. The only reason I made it home was BLIND LUCK. I’m a 72 year old Combat Marine and still “Kicking Ass”.——–Steve Kane

Was the RTO on the helo pad from October (pulled off with Maleria late October) back again in December to get wounded. Can’t find any reference of being bombed by our own jet as C2 was being attacked below us in October. Watched a ch 34 chopper crash in the LZ that night. It is like a dream. Surprised to see my picture in Life magazine Oct. 27, 1967. My mother was not happy. For more on this visit the web site for the Pennsylvania Veterans Museum and scroll down to interviews, Yes that is me talking about Con Thien.

Saw the mud comment above. Was familiar with ‘Kelly Humps’ (drainage dips) on Forest Service roads in Montana, and in early January 1968 was out scouting for locations to have our engineers bulldoze a few in. Mortar shrapnel found my magnetic left tibia and sent me home.