By Paul Garson

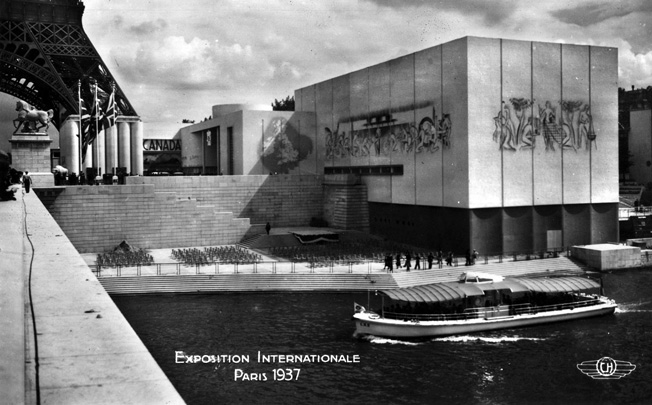

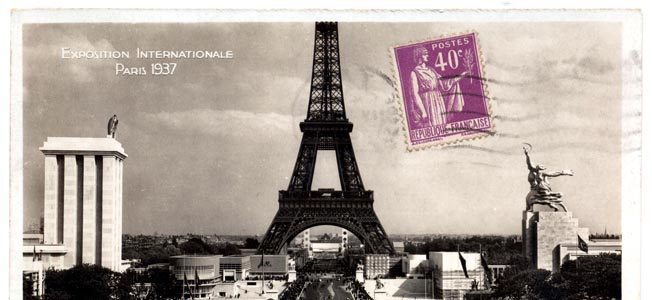

The 1937 Paris International Exposition once again centered world attention on the French capital that had previously been the stage for five world’s fairs, including the famous 1889 Paris Exhibition and the raison d’être for the construction of the Eiffel Tower, at 984 feet then the tallest structure in the world.

[text_ad]

Now, some 48 years after the 1889 Exhibition, the iconic tower was eclipsed by the appearance of two equally iconic structures, the German and Soviet Pavilions, facing off across a wide promenade. Their appearance and intent was in direct opposition to the avowed purpose of the 1937 Expo––to promote peaceful co-existence and cooperation among nations. The two buildings, in fact, presented the antithesis of that notion; they were cold, bellicose, and strident in design.

A “Brave New World”

The unheeded words from the event’s official program stated: “The objective is to be a meeting place for harmony and peace by not only striving to promote economic exchange between peoples but also the exchange of ideas and friendship. No advancement made in the fields of contemporary thought or science will be excluded. It welcomes all forms of activity in the spheres of industry and commerce.

“The 1937 International World Exposition therefore wishes to present a synthesis of all progress made by our generation. It will thus take stock of contemporary civilization. The outcome will educate all peoples, and highlight the areas where they should direct their efforts to maintain or improve their standing.”

Tumultuous currents of world events and conflicting ideologies influenced the 1937 Paris Exposition during its eight years in the making (the French Chamber of Deputies gave the go-ahead for the fair in 1929), most of them contentious for numerous political and economic reasons. Organization for the mammoth undertaking was controlled by the 42 members of the Upper Exposition Council under the direction of its president, Joseph Caillaus. The chief architects brought into the project were Charles Letrosne, Jacques Gréber, and Robert Martzloff.

As with any exposition of such magnitude, major problems continually cropped up and the work proceeded slowly; the original opening year was pushed back from 1936 to 1937. As the grand opening date of May 25 relentlessly approached, the French government was embarrassed to see other nations finish their pavilions and exhibits while bureaucratic delays and labor strikes delayed the host’s plans to complete the grounds.

Some of the other major developments that hampered the Expo’s progress were beyond the organizers’ control: a great, worldwide depression, the rise of fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, the bloody purges and murderous reshaping of Russian society under Stalin, the Spanish Civil War, the Japanese invasion of China, and the Italian occupation of Ethiopia. During those same years, Einstein brought forth the Theory of Relativity, Ganhdi led passive resistance in India against British rule, and Aldous Huxley published his novel, Brave New World.

The Paris Expo reflected that “Brave New World” in all its technical achievements as well as the book’s predictions of populations controlled by the dictates of all-powerful states. It was indeed shades of things to come; World War II was set to ignite two-and-a-half years after the gates opened on the Exposition.

In France, growing anti-Semitism helped fuel pro-Nazi rhetoric. In April 1936, French conservatives attacked the future French premier Leon Blum because of his Jewish ancestry and his strong anti-Nazi stance. A popular slogan of the day was “Better Hitler than Blum.” In France’s bitterly contested 1936 spring elections, the Communists and Socialists gained seats in the legislature, thereby increasing political divisions and friction within the country. The Far Right in interwar France, however, never took root and thus French fascism failed to gain wide-scale support. This was most likely due to the flexibility of the Republic’s parliamentarian system and its ability to forestall political polarization and the rise of fascistic tendencies, at least prior to the German occupation in 1940 and the resulting French collaboration.

Regarding its economic climate, the worldwide Depression did not affect France until 1931, when decreases in tourist revenues as well as a decline in demand for its exports (including perfumes and wine) caused a severe economic downturn. Unemployment bottomed out in 1935 at 15 percent, with production dropping 25 percent from 1929 levels. The French economy fell stagnant in 1932 and remained so into 1937. The Paris Expo was seen as one way out of its financial doldrums. For example, to buoy up the sagging condition of the city’s artists, Paris commissioned 718 murals, in the process employing over 2,000 artists specifically to decorate the numerous pavilions.

The Dueling Pavilions of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany had just produced the 1936 Berlin Olympics and was riding its own wave of international attention. A major public relations and marketing success for the Third Reich, the German staging of the Winter and Summer Games had impressed many of the foreign officials and members of the media who were wined and dined at gala parties during which Reichsminister Hermann Göring and other Nazi potentates expended huge sums of Reichsmarks to out-impress each other and their guests. The

Germans were intent on a similar success in Paris.

Designed by the wunderkind Albert Speer, Hitler’s favorite architect, the massive, imposing, and ominous German Pavilion was topped off by the national eagle and swastika as designed by approved Third Reich artist Kurt Schmid Ehmens, while the entrance was flanked by statuary created by Josef Thorack. As Arthur Chandler noted in a 1988 article in World’s Fair magazine, “The German eagle, its talons clutching a wreath encircling a huge swastika, disdainfully turned its head and fanned out its wings. At the ground level, a massively naked Teutonic couple stare at the Russian monument with grim determination.”

While Speer, always self-serving, later said he “stumbled by chance” upon the Soviet pavilion plans, the efficient German intelligence services apparently had supplied Speer with a description of the Soviet design. The report further interpreted the striding group of Russian hammer-and-sickle figures atop the structure as “symbolizing a Soviet invasion of Germany.” Speer then apparently set forth to model the German “defensive” response with a representation of the classic Deutsche Haus, as he stated a “cubic mass shaped by massive pillars.”

In their “monumentalism,” both the German and the Soviet designs were created to present an aura of power and permanence. Both also used bronze surfacing over their main images or ideological “logos”––the swastika in the case of Germany and the hammer and sickle for Soviet Russia.

Both building designs were also windowless, with no light either entering or escaping, the visitors sealed within and subject to whatever sounds and sights awaited them. Both pavilions appeared sepulchral in form and atmosphere, although not so intended by their designers, at least consciously.

A Pavilion Built by Hitler’s Architect

One can easily see the classic European cathedral in the floor plan of the German structure, a fact not lost on the leaders of National Socialism who sought to eliminate traditional religion, replacing it with “Religion of the State.” While there were no gun towers or rifle slits, the echo of castle fortifications is easily identified, the Nazi state representing itself as a bastion of power––both a sanctuary and a bulwark against the wave of “Asiatic Bolshevism” that it faced off against in literal terms at the Expo. While expressions of fundamentally opposed ideologies, the similarities were equally apparent, with both structures extensions of the two individual megalomaniacal warlords, Hitler and Stalin.

The interior decor of the German Pavilion was the provenance of another approved Nazi designer, Waldemar Brinkman, who, perhaps taking his cue from Speer’s use of 130 searchlights to create the famous 1937 Nuremberg rally “Cathedral of Light” spectacle, also utilized aura-enhancing lighting effects.

Upon entering the pavilion, one encountered 15-foot-high bronze doors by ascending an equally large-scaled staircase. The next effect was an elegant foyer, again dramatically lit, this time by chandeliers. Set upon an altar-like platform were models of Third Reich construction projects, Herculean in scope, power, and impact.

Other rooms displayed German cinema, television, and radio innovations, all part of a mesmerizing multimedia assault on the senses. Other technological marvels included the Hollerith Machine Company’s Dehomag D11 tabulating machine (a precursor of the computer the Nazis put to use recording data concerning the vast number of prisoners held in German concentration camps. Somewhat ironically, three weeks after the opening of the Paris Expo, the Buchenwald concentration camp back in Germany was opened).

Visitors upon entering found the displays of German technical, design, arts and manufacturing accomplishments set up in a deliberately “cozy” ambiance, in contrast to the cold technocratic design of the Soviet pavilion.

Boris Iofan’s Mantra of Collectivism

While Speer was given command of the German Pavilion design, that dubious honor for the Russian Pavilion was handed over to Boris Iofan, whose life literally depended on its outcome.

The structure’s crowning 79-foot-tall figures, true to the Soviet mantra of Collectivism, a program that had condemned millions to death by starvation, were renderings of “cooperative farm maids and workers” as stated in the Stalinist parlance of the times.

While Hitler and the Nazi Party had only four years earlier gained controlling power in Germany, one must remember that 1937 was a year of great significance for the Soviet Union as it marked the 20th anniversary of the October Revolution. Within the pavilion’s natural-stone-clad walls, the “heroic achievements of the Revolution” were represented in large-scale panoramas depicting the colossal advances of socialism in the “Workers’ Paradise.”

Inside, spectators found a large map of Russia comprised of gold, rubies, and other precious stones, certainly awe inspiring but almost czarist in its opulence. Highlighting the “great leap forward” to a modernized Russia, on display was a 1934 Ford manufactured in a Russian factory and also a copious amount of what a Life magazine correspondent described as “kindergarten communist propaganda.”

Needless to say, the magnificence of the Soviet Pavilion pleased Stalin and architect Iofan kept his life––and went on to design many more Stalinist edifices until his death in 1976.

Other Attractions of the Expo

In addition to the German and Soviet presentations, other pavilions were commissioned by a total of 44 countries, including Argentina, Egypt, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Uruguay, Spain, Switzerland, and the Vatican, among others.

The United States pavilion, designed by 42-year-old German-born architect and urban planner Paul Lester Weiner, was a towering skyscraper that showcased the Roosevelt administration’s New Deal and was filled with displays highlighting America’s efforts to pull the nation out of depression.

Seemingly contrary to the ultra-modern aesthetic of the event, “peasant art” also figured prominently in more than 60 pavilions, representing contemporary national styles in the Hungarian, Romanian, Polish, and Portuguese pavilions, while the French displayed artwork from their various colonies (along with the patronizing pronouncement that they were bringing enlightenment to the inhabitants of those countries). In addition to the national pavilions, there were also Railroad Pavilions and Air Pavilions that showed off the latest transportation designs.

Two large, curved, modernist structures known as the Chaillot Palace, across the Seine from the Eiffel Tower, served as the Exposition’s main art museum and replaced the Trocadero, a leftover from the 1878 fair.

In addition to art, the Expo also included a wealth of events and competitions as well as 600 congresses, motorboat races on the Seine, a dance festival, horse racing, colorfully lit water fountain displays, World Championship boxing matches, and 42 other international sporting competitions.

The variety of entertainments included a 243-foot-tall parachute jump tower for those visitors wishing to experience jumping out of an aircraft without actually doing so.

More than 31 Million Visitors

After it closed on November 25, the final tabulations as to the scope of the 1937 Paris Expo included some 11,000 exhibitors who found themselves inundated by more than 31 million visitors, each of whom were required to purchase a six Franc entry ticket (about 25 cents in U.S. currency). While the official French figures from 1937 indicate the Expo went considerably into the red, it also claimed that other collateral financial benefits occurred. For example, over four million more people attended theatrical and musical performances than did in 1936, and admissions to the Louvre and Versailles doubled; Paris’ famous underground transport system, the Métro, collected 59 million more fares.

Revised financial data later published in 1940, with France under German domination, reported income from the Expo totaled nearly 1.66 billion Francs, while expenditures totaled some 1.5 billion Francs and showed a purported profit of about 218 million Francs, equaling a value then of $1.5 million U.S.

Although the Expo’s organizers stated loftier goals (“Peace and Prosperity”), Arthur Chandler wrote, “The 1937 exposition marks the first time that an exposition is launched in order to shore up a sagging economy and to provide jobs for the unemployed.”

The 1937 Paris Expo opened on May 25 and closed on November 25, 1937––a run of 185 days. A total of 16,704 medals went to the winners among the 44 exhibiting nations, including gold medals to both Speer and Iofan for their pavilion designs. Speer also was awarded a Gran Prix for his scale model of the Nuremberg Nazi Party rally grounds. The various representatives then applauded each other before leaving for home, wary of the darkening war clouds on the horizon. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments