By Jim Haviland

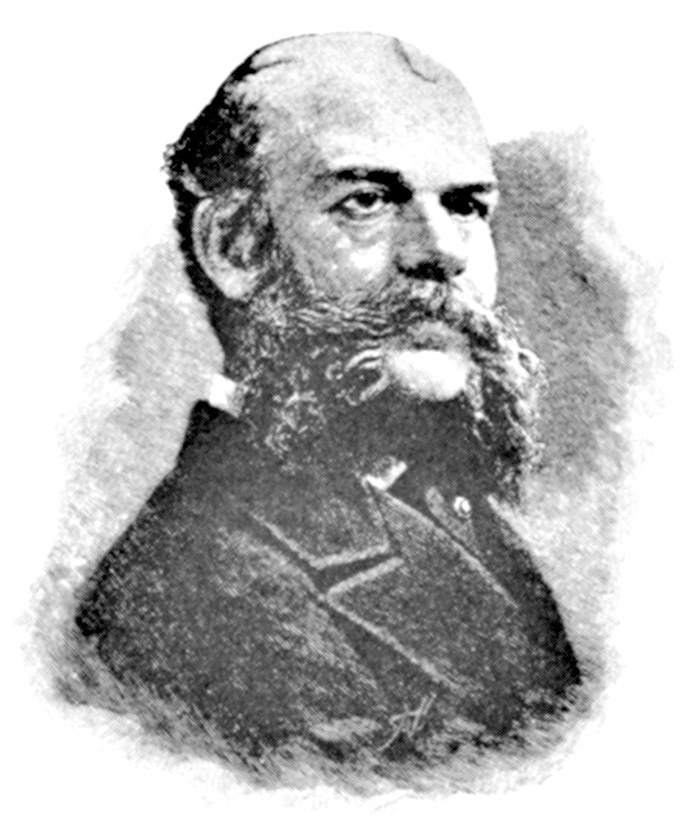

Although Confederate commander James D. Bulloch had a well-rounded naval background, he also proved skillful as a secret agent. His talents were dearly valued for their efficacy in England, from whence the fledgling Confederacy hoped to secure ships for the navy it would need to survive. The Southern states lacked the capabilities for the kind of naval construction they needed.

Bulloch was a Georgia native. His half-sister became the mother of Theodore Roosevelt, destined to become U.S. president in 1901. Bulloch himself became a midshipman in the U.S. Navy at a young age in 1839. He then served on a variety of ships, including the Delaware while on a famous Mediterranean cruise.

During 1844-1845 Bulloch attended the naval school in Philadelphia, finishing second in his class. Back on active duty, he moved to the Pacific coast during the Mexican War. He then became commander of a mail steamer traveling to California, and subsequently commanded various vessels providing mail service along the Gulf of Mexico.

Bulloch Heads to England to Secure Ships

When Georgia seceded from the Union, Bulloch resigned his Federal commission, then was commissioned a Confederate Navy commander. Because of his skills in maritime and international law, he was appointed its naval agent in England to acquire ships for the South. He accepted the duty with one condition—getting command of the first Rebel cruiser fitted out in England.

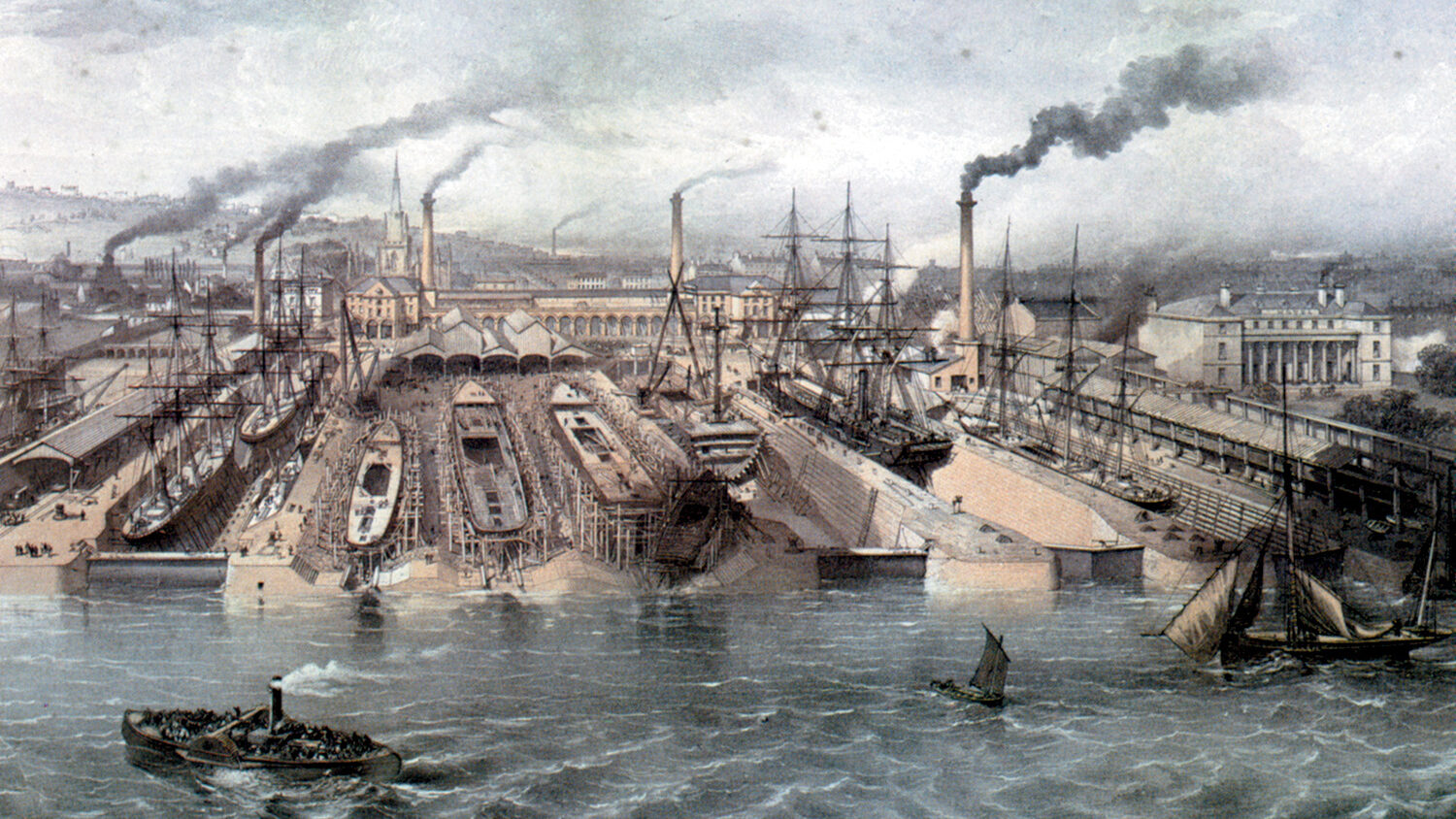

In Liverpool in 1861, Bulloch made arrangements to start construction of two cruisers—the Florida and the Alabama. He then hunted for a vessel that could be used to haul needed military and naval supplies through the Union Navy blockade off the Confederate Atlantic coast.

For the blockade-running operation, Bulloch, who knew ships and shipping as few people did, bought the Fingal, an almost new propeller-driven steamer. Although he had dreamed of captaining one of the two cruisers being built in England, Confederate higher-ups insisted that acquiring naval vessels was far more valuable than taking the time off to direct a battle cruiser on a long and arduous voyage.

But Bulloch was successful in securing permission to captain the Fingal for just one trans-Atlantic voyage to transport needed war supplies. When back in the South, he personally updated Stephen R. Mallory, the Confederate Secretary of the Navy, on his secret operations and difficulties in acquiring warships and blockade runners for the South.

After seeing the Fingal make 13 knots on a test run, Bulloch took possession of the ship in Greenock, Scotland, although he did not stay aboard. “It was necessary to act with caution and secrecy,” Bulloch reported later, “because the impression had already gotten abroad that the Confederate government was trying to fit out ships in England to cruise against American commerce. All vessels were closely watched.”

The Secret Voyage of the Fingal

For deception, the Fingal initially had to be kept under the British flag, with an English captain hired for the outward voyage from Scotland. Crew members signed on under Britain’s Merchant Shipping Act requirements. Pains were taken to get good engineers and a few leading men. All this was done with no hint of the ship’s true destination.

The Fingal was secretly loaded in Scotland. It was to be the largest haul of military supplies ever attempted for the Confederacy. Other hauls may have been larger, but those were for civilian goods already in short supply in the South. Privately owned blockade runners found it more profitable to haul luxury goods than military ones.

The Fingal’s military cargo included a variety of rifles and revolvers, two 41/2-inch muzzle-loading rifled guns and two breech-loading 21/2-inch steel-rifled guns for boats. There also was a generous supply of ammunition and a large amount of seamen’s clothing.

Bulloch returned to Liverpool, where he received word that the Fingal had left Scotland on October 11, 1861. But off the coast, she encountered a large gale with heavy rain lasting several days. With no word of the Fingal’s whereabouts in

the storm, Bulloch feared the mission might be over before it truly began.

Then, unexpectedly, Bulloch was awakened at about 4 am on October 15 by Mr. Low, the Fingal’s second officer, dripping wet. While still half asleep, Bulloch picked up only the words “Fingal,” “brig,” “collision,” and “sunk”—fearfully jumbled together. He formed a mental picture of the Fingal sunk at the bottom of Holyhead Harbor by Liverpool.

Low explained that the Fingal had collided in a storm with an anchored wooden brig with no light, sinking it. Rushing to the scene, Bulloch learned the sunken brig was the Austrian Siccardi, which was loaded with coal.

Knowing that the Fingal, with its secret cargo of weapons, couldn’t remain there to await an inspection by Customs officers, Bulloch went aboard and made immediate arrangements to sail. “If the Fingal stayed, there would surely be an inquiry, further detention, and perhaps a final break-up of the voyage,” he explained.

Fortunately for his cause, Bulloch got the Fingal around the harbor breakwater and steaming down the channel before the accident could become known to anyone with authority to stop her. He contacted Fraser, Trenholm & Co., representing Confederate financial interests in England, and instructed the firm to arrange a friendly money arbitration with the brig’s owner.

Because the steamer “had been loaded too deep” with its military cargo, Bulloch found it impossible to maintain speed higher than nine knots when at sea. “It was rather disappointing in view of a possible chase between Bermuda and the [Southern] coast,” he pointed out.

Bulloch Reveals the Real Mission to the Crew

In any event, the steamer arrived in Bermuda without further incident on November 2. There Bulloch met with Captain R.B. Pegram of the Confederate ship Nashville to learn about beleaguered Confederacy affairs. In addition, the Fingal took aboard from the Nashville a pilot named John Makin, who was familiar with Savannah and its inlets.

Then the Fingal was detained several days. The U.S. consul in Bermuda suspected the steamer was a blockade runner and tried to prevent it from taking on coal and other supplies. He even hired men to try to alarm the crew and frighten them into leaving. But friendly local merchants saw that the Fingal got everything she needed to sail for Nassau on November 7.

Although the U.S. government was unable to stop the military shipment, its consul in London dispatched a full report on the Fingal and its cargo. Thus a detailed description and a sketch of the vessel were sent to captains of the Union blockading fleet so they would recognize her.

Up until the sailing, nothing had been mentioned to the crew, or even the British captain, about the true purpose of the voyage. So when it was time to point the Fingal toward Savannah instead of Nassau, Bulloch called a meeting and told the crew their true destination. This meant running the blockade, thus risking capture and some rough treatment as prisoners of war.

“If you aren’t willing to go on, say so now, and I’ll take the ship to Nassau and get other men who will go,” the Georgia native said. “But if you’re ready and willing to risk the venture, remember that it’s a fresh engagement and a final one. From which there must be no backing out.” Not one of the crew expressed a desire to leave.

Bulloch then told the crew the Union had bought merchant service steamers for blockaders, many being neither strong nor efficient. “They’re not heavily armed,” he claimed.

The commander said the Confederate government wasn’t willing to give up the Fingal’s valuable cargo to a Union ship not strong enough to successfully attack, or to men in open boats attempting to board the steamer.

“So long as the Fingal is under British flag, we have no right to fire a shot,” Bulloch said. “But I have a bill of sale in my pocket and can take delivery from the captain to the Confederate Navy at any moment.

“If there should appear any likelihood of a collision with a blockader, I want to know if you’re willing to help in defending the ship,” he asked.

“Yes,” they all answered.

With that settled, all hands went to work arming the Fingal. They mounted the two 4 1/2-inch rifled guns in the forward gangway ports and the two steel boat-guns on the quarterdeck. With a sufficient number of rifles and revolvers and enough ammunition, they converted the “ladies saloon” into an armory, shell-room, and magazine.

Bulloch later conferred with McNair, the chief engineer, who reported putting aside a few tons of the nicest, cleanest coal. McNair said that if a he had time before reaching the Southern coast to haul fires in one boiler at a time and run scrapers through the flues, he felt he could drive the ship—deep as she was in the water—at 11 knots for a few hours’ spurt.

The Fingal Attempts to Run the Blockade

McNair got his chance on November 11, when Bulloch wanted to make land at the entrance to Wassaw Sound south of Savannah. From there the plan was for pilot Makin to find a way for the ship to navigate the inland creeks until reaching the Savannah River upriver from the Union threat.

The Fingal was opposite Wassaw Sound about noon, and Bulloch had the steamer head due west—setting the speed to make land before daylight. About 1 am on November 12, they got shore soundings. “Up to this time it had been uncomfortably clear, with a light southeast breeze,” reported Bulloch later. “But it now fell calm, and we could see a dark line to the westward. Makin said it was the mist over the marshes. And the land-breeze would soon bring it off to us.”

There wasn’t a light anywhere on the ship except in the binnacle, with that carefully covered so the wheelman could barely read the compass. Not a word was spoken. The only sound was the throb of the engines and the slight “shir-r-r” made by the ship’s friction through the water, and even that was seemingly muffled by the dank and vaporous air.

“When we got into six fathoms, the engines were eased to dead slow,” said Bulloch. “And we ran cautiously straight for the land, the object being to get in-shore of any blockaders that might be off the inlet.

“The fog was thick, about the color of mulligatawny soup, and the water alongside looked darkish brown,” the commander reported. “From the bridge it was just possible to make out the men standing on the forecastle and poop. We could not have been in a better position for a dash at daylight.”

The Mission is Nearly Cocked Up

With every eye searching the fog for the first glimpse of land—or an approaching ship—a prolonged, shrill, quavering shriek suddenly burst upon everyone’s ears.

“The suddenness of the sound, coming upon our eagerly expectant senses, and probably much heightened in volume and force by contrast with the stillness, was startling,” reported Bulloch. “None of us could conceive what it was. But all thought that it was loud and as piercing as a steam whistle. And that it must have been heard by any blockader within five miles of us.”

In a moment the sound was repeated. But the crew detected its source, because it was accompanied by a flapping and rustling noise from a gangway hencoop. “It’s the cock that came on board at Bermuda,” someone said.

Several men ran to the spot and one drew out an unhappy fowl. They wrung off its head with a vicious swing.

“But it’s the wrong one,” said Bulloch.

Sure enough, the offending bird crowed once more, defiantly.

“Try again,” a voice said in an audible whisper from under the bridge.

“But the man’s second effort was more disastrous than the first,” Bulloch recalled. “He not only failed to seize the obnoxious screamer, but set the whole hennery in commotion. With the ‘Mujan’ cock, from a safe corner, crowing and croaking, and fairly chuckling over the fuss of feathers, the cackling, and the distracting strife aroused.”

At last the offending bird was caught. “He died game,” Bulloch emphasized, “and made a fierce struggle for life. The body fell with a heavy thud upon the deck and we were again favored with a profound stillness.”

The Final Sprint for Shore

As daylight began to break Makin said the fog would settle and gather over the low marshes toward sunrise and gradually roll off seaward before the light land breeze. Because of the fog problems, Makin felt he would have trouble finding his way through the inland creeks to the Savannah River.

Instead, he proposed making a dash for Savannah, about 18 miles to the north and east, feeling sure the Fingal could get in there, buoys or no buoys.

McNair again readied the Fingal to make a good 11 knots to speed the trip.

The fog continued to settle and roll off the land. It hung heavily, a gray mass, almost black at the water’s edge, serving as a veil between the Fingal and any blockaders enveloped in it. Eventually, the Fingal was over the bar and plowing up the channel.

“We fired a gun and hoisted the Confederate flag at the fore,” said Bulloch. “Which was answered from the fort [a Confederate one, near Savannah].” It was lined with men as the Fingal drew closer. The fort’s garrison waved their caps and cheered.

After docking, Bulloch hurried off to report to Confederate authorities in Richmond. The Fingal was unloaded of its war supplies and then loaded again with cotton for the return voyage. But during the interval the Federal blockading fleet closed in on Savannah.

When the Fingal was ready for its easterly voyage, Bulloch spent weeks trying to elude the many blockaders to get his ship out, but found no success. After bringing the Fingal across the Atlantic with such ease, she now turned out to be an unlucky ship for the Rebels.

Bulloch finally gave up and traveled up to Wilmington, NC, to catch the blockade runner Annie Childs for his return trip to Liverpool. He arrived March 10, 1862, just as the cruiser Florida was getting ready to sail.

Bulloch continued to work to secure ships for the South. His legal status regarding his rights in Britain for procuring men-of-war was even sustained by the English courts. But Her Majesty’s government was also pressured by the Lincoln Administration, and the shifting British policy made Bulloch’s work increasingly difficult.

The Fingal’s Disappointing End

Back across the Atlantic, the Federal blockade fleet kept the Fingal bottled up so long in the Savannah River that the Confederacy decided to transform her into a different kind of vessel. She was stripped and covered with thick armor, shielding the four large naval guns.

Renamed the CSS Atlanta, she steamed down the Savannah River as a fighting ironclad late in May 1863. But she drew so much water with her deep hull and heavy armament that she soon ran aground on a mudbank.

Ultimately she was floated off and repaired. She tried again in the dead of night of June 17, setting out to attack a fleet of Federal monitors. But she ran aground three times as she neared the small and well-armed Union ships.

When Captain John Rodgers, commander of the USS Weekawken monitor, saw the clumsy Atlanta was unable to move, he ordered his Union vessel to close in and blast away with its enormous 15-and 16-inch guns.

Forced to surrender, the Atlanta was taken as a prize of war and assigned to the Federal fleet.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments