By John Wukovits

Lieutenant Tom Bronn glanced anxiously at the fuel gauge on his Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber. He had been aloft for almost four hours, engaged in a hectic combination of trying to locate Japanese ships he knew to be in the Philippine Sea, diving down to unleash his four bombs at a carrier as dusk enveloped his aircraft, and then embarking on a desperate search for his own carrier, the USS Lexington, in the darkness.

Bronn knew, from what the fuel gauge indicated, that he had only moments left before he would be forced to ditch, a quite unwelcome ending to an otherwise successful assault. The angry ocean was not a place to be in the dark.

Fortunately, a warm welcome awaited him, for someone had ordered every American ship in the force to turn on its lights, illuminating the shadowy waters so that Bronn quickly spotted what he thought was the Lexington. As he entered his final approach to the carrier, Bronn had to dodge other American fighters, dive- bombers, and torpedo bombers frantically attempting to land. They all faced the same quandary: set down quickly or endure a hazardous nighttime splash into the Pacific.

Bronn made his first pass at the Lexington, but had to pull out when he saw the carrier’s deck littered with the remnants of a crash that had occurred only moments before. By now, Bronn knew he had to be running on fumes alone, but he circled around to make two other attempts to land. Both times, he had to pull out.

Bronn now had no choice but to ditch his torpedo bomber. He stared around and noticed a nearby destroyer, veered toward the vessel, and settled his craft into the water as smoothly as he could. When a sudden jar indicated he had hit the water, Bronn and the two men flying with him hustled out of their harnesses and climbed out of the floating aircraft. A few minutes later a voice boomed out from the destroyer that it would be back for them shortly. Thus reassured, Bronn felt his worries were over.

Minutes ticked away, however, and still no ship appeared. Suddenly, a second vessel, the cruiser USS Reno, steamed alongside and retrieved the three weary, wet aviators. Fellow Navy personnel helped them climb aboard, then guided them to the ship’s sick bay, where Bronn and his crewmates answered questions about their flight before settling in for a well-deserved rest.

Bronn’s battle had originated in the ashes of a pair of monumental clashes enacted two years earlier. In those conflicts—the May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea and the June Battle of Midway—much of Japan’s aircraft carrier strength had disappeared beneath the Pacific surface, the victims of American intelligence, courage, and incredible good fortune. Since that time Japan had slowly rebuilt her air groups, with the intent of again engaging the Americans in a decisive battle that would terminate the American advance across the ocean.

By 1944, the Japanese Navy appeared ready to strike. All it needed was the right time to set its trap. Japanese naval leaders saw an opportunity to meet the Americans at one of two avenues of advance—the Caroline or Palaus Islands north of New Guinea or the Marianas Islands in the Central Pacific—depending upon which thrust the Americans favored. To be ready no matter which path the Americans followed, in May 1944 the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, issued the A-Go plan.

The commander of the First Mobile Fleet, Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, received almost every available surface craft to meet the Americans. Five fleet carriers, the Taiho, Junyo, Hiyo, plus Shokaku and Zuikaku, veterans of the Pearl Harbor attack, anchored the powerful force, which included backing from the light carriers Ryuho, Chitose, Chiyoda, and Zuiho. As a protective shield for the carriers, Ozawa counted no fewer than five battleships, 12 cruisers, and 22 escorting destroyers.

Ozawa’s main strikes were to be delivered by his air arm which, on the basis of pure numbers, posed a formidable threat to the oncoming American carriers. Ozawa had assembled 430 carrier aircraft, plus he could count on an additional 540 fighters and bombers from land-based locations.

Ozawa relied on these land-based planes to chip away at the enemy fleet and destroy as much as one-third of the American strength before closing with the Japanese. His lightweight carrier planes, which enjoyed as much as a 100-mile range advantage over their heavier, armor-plated American counterparts, would then swoop down to finish the job begun by their land-based compatriots before the Americans pulled close enough to launch their own attack. Thus would be avenged the alarming number of defeats that followed the heady days of late 1941 and early 1942, when the Japanese military stampeded across the Far East and the Pacific Ocean.

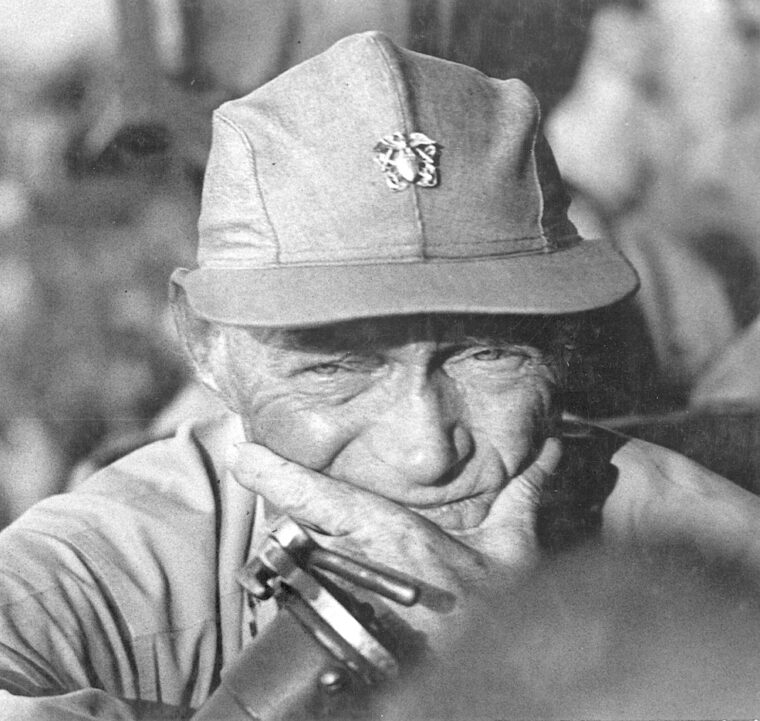

Admiral Raymond Ames Spruance Became Known for His Competence and Extreme Calm Under Heavy Pressure

On paper, the 970 aircraft posed a lethal threat to any American surface force that moved unknowingly into Ozawa’s trap, but a closer examination of the situation revealed the Japanese strength to be surface-deep. They certainly possessed sufficient aircraft to challenge the Americans, but they lacked a crucial ingredient to attain victory: enough talented aviators to man the machines. Japan’s aerial supremacy occurred early in the war, in part because of the skills of its daring airmen. In the intervening two years, however, a series of naval encounters had steadily diminished their ranks. Worn down by combat attrition and by accidents, expert fliers sparsely populated the ranks of Japanese airmen. The vast percentage of pilots came fresh out of training and lacked the experience so necessary for combat. In an effort to rush airmen to the fleet, Japan had also cut back on the amount of training.

One stereotype that existed during the war was that of the stoical Japanese leader, a competent individual who calmly executed his orders and rarely allowed emotion to affect his performance. The Battle of the Philippine Sea boasted such a man, but on the American side, not the Japanese. Admiral Raymond Ames Spruance earned a reputation for intelligence, logical evaluation of problems, and extreme coolness under difficult circumstances.

Ever cautious, Spruance intended to deploy his fleet in a conservative manner. His primary responsibility was to shield the Saipan invasion forces, especially the valuable troop and supply transports, from a Japanese sea assault. Since the American assault of the Marianas Islands represented a huge leap toward Japan, Spruance assessed a high likelihood that the enemy fleet, including carriers, would sally out to meet the Americans.

As tempting a target as these carriers posed, Spruance decided beforehand that he would only pursue the foe and abandon the area near Saipan if he concluded the men ashore and the transports were safe from attack. Until then, he intended to steam within range of Saipan and avoid being lured away. If he could both protect Saipan and steam out to meet Ozawa, he would do so, but he would not forego his primary responsibility to chase after Japanese carriers.

Spruance realized that many naval leaders, especially those with a background in aviation like his counterpart in the Pacific, the bullish Admiral William F. Halsey, disagreed with this tactic. They would not hesitate to pursue the carriers, believing they posed the greater threat. A student of previous campaigns, however, Spruance noticed the Japanese tendency to include feint moves in their operations. They had done so at Midway, and a recently captured Japanese document emphasized the use of feinting toward the American middle to draw out the enemy while a flank attack dashed around one end to hit from the rear. Spruance feared the Japanese would attempt to lure him away from Saipan with one force, while other units steamed in on an end run to attack Saipan’s beachhead.

On June 6, 1944, as the mighty Allied armada prepared to smash against Hitler’s fortifications in France to begin the liberation of Western Europe in the vast D-day operation, Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher guided his Task Force 58 out of Majuro Harbor in the Marshall Islands and set course for the Marianas group 1,600 miles northwest. In an awesome display of what American factories had produced in a relatively short time, Mitscher commanded an invasion force almost as impressive as his counterparts in Europe. History has rarely, if ever, seen one nation simultaneously mount two such widespread campaigns involving so many men, ships, and aircraft.

Five hours elapsed before the final ship of Task Force 58 exited Majuro Harbor. Sailors and officers marveled that they had never seen such a collection of weaponry, and wherever they looked ships dotted the waters stretching to the horizon. Mitscher’s 100 ships steaming in formation blanketed 700 square miles of ocean.

Mitscher’s power centered in the four task groups under his command, each anchored by aircraft carriers. Task Groups 58.1, 58.2, and 58.3 each contained four carriers, among them the Hornet, Yorktown, Wasp, Enterprise, and Lexington, while Task Group 58.4 added another three carriers to the mix. Among them, the carriers bore 900 aircraft to hurl at the enemy, including the superb new Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat fighter. Steaming with them, riding as deadly compatriots as well as buffers against attack, were four heavy cruisers, 13 light cruisers, and 49 destroyers. A fifth collection, Task Group 58.7, formed Mitscher’s battle line of seven battleships, four heavy cruisers, and 13 destroyers.

Buttressed by this seagoing spectacle, the Americans felt confident they could handle any threat posed by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Life magazine correspondent Noel F. Busch talked to Mitscher on June 9. The admiral explained that he expected to have to fight his way toward Saipan. Busch was surprised at the admiral’s attitude. “The admiral seemed pleased rather than otherwise by this prospect.”

Busch found Mitscher’s pilots to be just as eager for a fight. Aviators boasted to Busch that they hoped the enemy appeared instead of staying out of the fray. Busch wrote that the men pined for a contest “so that they can improve their scores of Japanese planes shot down.”

Spruance’s first task was to attain air supremacy over Saipan, not simply to support the ground forces but also to safeguard his ships off the island while they landed and then supported the assault. By immediately grabbing air supremacy, Spruance would eliminate the specter of shuttle-bombing, in which Japanese planes launched from their carriers, hit their targets, and then landed on friendly airfields in the region rather than having to return to their carriers. This tactic gave the Japanese aircraft greater range and handed them the opportunity to launch while still outside the attack range of American carrier-based fighters. Tied to the beaches to protect the landing force, Spruance could not allow shuttle-bombing to happen.

The Well Trained American Pilots Slaughtered the Inexperienced Japanese Zero Fighters

Spruance wasted little time in achieving his goal. In two days of heavy air raids on June 11-12, American carrier fighters and bombers ripped into enemy airfields on Guam, Rota, Saipan, and Tinian, all islands within easy range of the landing force approaching Saipan. Fighters riddled airfields and parked aircraft with their bullets, while bombers devastated facilities and airstrips. Japanese Mitsubishi Zero fighters rose to meet their foes, but the inexperienced pilots proved no match for their better trained American counterparts and their superior Hellcats.

A slaughter ensued, and when the final wisps of smoke cleared away, American pilots had shorn Ozawa of his sorely needed land-based air power. Had Ozawa learned of this, he might have acted differently in the coming battle, but in one of those amazing lapses that often occur in war the commander of the decimated squadrons, Vice Admiral Kakuji Kakuda, failed to relay this vital information to his superior. Ozawa prepared to sail on toward the Americans, blissfully unaware that one of his offensive arms had been so brutally severed.

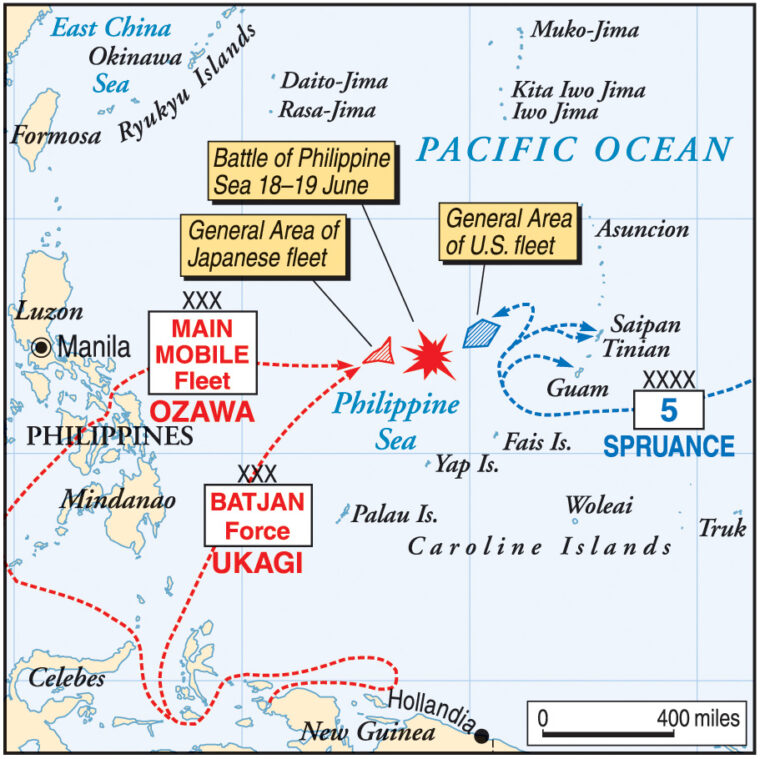

Ozawa sortied from Tawi Tawi in the Sulu archipelago on June 13, the same day that Mitscher’s battleships moved into position off Saipan’s shores and commenced their preinvasion bombardment to soften up the enemy for the assaulting troops. As he inched eastward, Ozawa split his force into three segments. An advance group, commanded by Admiral Takeo Kurita, posed as the bait with which Ozawa hoped to lure Spruance. To tempt the Americans, Kurita possessed the carriers Chitose, Chiyoda, and Zuiho along with 88 aircraft and a potent screen of battleships and cruisers.

One hundred miles behind, waiting to spring the trap set by Kurita, Ozawa steamed with his main force of two groups. Group A, with Ozawa in tactical command, contained the carriers Taiho, Zuikaku, and Shokaku and their 207 aircraft, while Rear Admiral Takaji Joshima’s Group B added the carriers Junyo, Hiyo, and Ryuho and 135 aircraft. Once Spruance had taken the bait and attacked Kurita, Ozawa would launch his counterattack, take the Americans by surprise, and attain a great sea victory. Shorn of air cover, the Americans could then do little to halt Ozawa’s carriers, battleships, and cruisers from controlling the waters around Saipan.

On June 15, D-day at Saipan, Ozawa received a message informing him of the American assault and orders to “attack the enemy in the Marianas area and annihilate the aviation force.” The message from his superiors added urgency to the situation by describing the coming operation as a “decisive battle.”

American submarines quickly reported Ozawa’s departure to Admiral Spruance, who rightly figured they were heading his way. He ordered the transports off Saipan to continue unloading supplies until June 17, then withdraw to the east so that Spruance would be free to fight the impending battle to the west. Spruance, under orders to first protect the invasion forces and second to chase after Japanese surface forces, had already decided he would not steam beyond aircraft range of Saipan. He would launch a strike against the Japanese if conditions warranted, but if he felt the invasion beaches were threatened, he wanted to remain close enough to fashion a protective shield.

The Japanese readied for the battle they hoped would atone for their defeats at the Coral Sea and Midway. Ozawa brought cheers and grim determination to officers and sailors alike by turning to one of his nation’s most revered heroes. Immediately prior to the titanic Battle of Tsushima against Russia earlier in the century, Admiral Heihachiro Togo flashed a famous message. Ozawa utilized the same words: “The fate of the Empire rests on this one battle. Every man is expected to do his utmost.”

The coming battle now boiled down to which side located the other first and launched the initial air strike, which meant that search planes and submarines played a crucial role in setting the stage. As June 18 unraveled, both combatants steamed about the Philippine Sea like two cautious bulldogs sizing one another up. Ozawa knew that Spruance carried a heavier punch than the Japanese, so he had to be careful lest he lead his ships recklessly into an awkward situation.

Spruance, on the other hand, worried about the longer range enjoyed by Japanese aircraft, had all search planes keeping wary eyes out for the Japanese fleet. In addition, to prevent another Japanese end run, he told his staff, “Until we know exactly where the enemy is, we must be positive that we are between his possible locations and those landing ships.”

June 18 almost slipped away without either force learning the whereabouts of the other, but shortly before dusk, Japanese search planes spotted Spruance. With so little daylight remaining, Ozawa refrained from sending his aircraft until the following morning. He also hesitated to order an immediate strike because he had unreliable information about the condition of airfields on Guam, where his airplanes would land after attacking Spruance. In light of the American assault of the Marianas, he did not know if the airfields were usable or if they were pockmarked with bomb craters from American attacks.

Shortly after Ozawa’s search planes located the American force, Mitscher’s planes stumbled across the Japanese. Mitscher’s Task Force 58 had been steaming to the west for most of the day without success. As darkness neared, Spruance ordered Mitscher to reverse course and steam to the east so his carriers would be in position to protect Saipan. However, an intercepted signal from the Japanese commander to a land-based officer provided a fix on the Japanese position. Ozawa was steaming 355 miles to the west-southwest of Mitscher.

The capable American commander saw a tailor-made opportunity to land the first blow. Mitscher requested permission from Spruance to reverse course yet again and head west during the night. This would close the distance between the two forces, place Mitscher in position to launch a strike at daylight, and catch the enemy unaware.

“The Enemy Could Attack Us at Will at Dawn the Next Morning. We Could not Attack the Enemy.”

Mitscher and his staff assumed Spruance would acquiesce and quickly issue orders to enact the plan, so they reacted with astonishment when he radioed back that they were to continue steaming east. He replied that an “end run by other carrier groups remains a possibility and must not be overlooked.”

The aviators of Mitscher’s staff argued that Spruance had abandoned an excellent opportunity to land a knock-out punch, had adopted a defensive rather than an offensive posture, and had yielded the initiative to the enemy, who would steam unmolested toward Spruance and the American fleet all night. Ozawa would then have moved close enough to the American carriers to launch an air strike, yet remain distant enough so that the shorter range American aircraft could not hit back. Captain Arleigh Burke, commander of the Lexington, summarized the prevailing feeling when he later stated, “This we [aviators] did not like. It meant that the enemy could attack us at will at dawn the next morning. We could not attack the enemy.”

Spruance’s decision produced an avalanche of criticism after the battle, but he had logical reasons for keeping his carriers reined close to Saipan. Ozawa laid out what he thought was a perfect trap. Kurita’s van would draw out the Americans, then Ozawa’s main force would rush in and finish the destruction.

Had Spruance allowed Mitscher to steam west during the night and launch a dawn attack against Ozawa’s carriers, his pilots would have had to fly straight through a complex system of Japanese defenses. They would first have faced a lethal curtain of antiaircraft fire from Kurita’s ships, then encountered a second from Ozawa’s guns and aircraft 100 miles farther on. After dropping their bombs, the Americans would have had to again fly through Kurita’s guns.

The attack would have undoubtedly destroyed a large number of Ozawa’s planes, but the Americans also would have lost a significant number of their own—planes that would not have been present for the slaughter about to unfold on June 19. By retaining his full complement of aircraft, Spruance enjoyed an overwhelming concentration of air power with which to handle Ozawa’s inexperienced aviators the next day and to deliver an even greater victory than Mitscher probably would have achieved with his dawn attack.

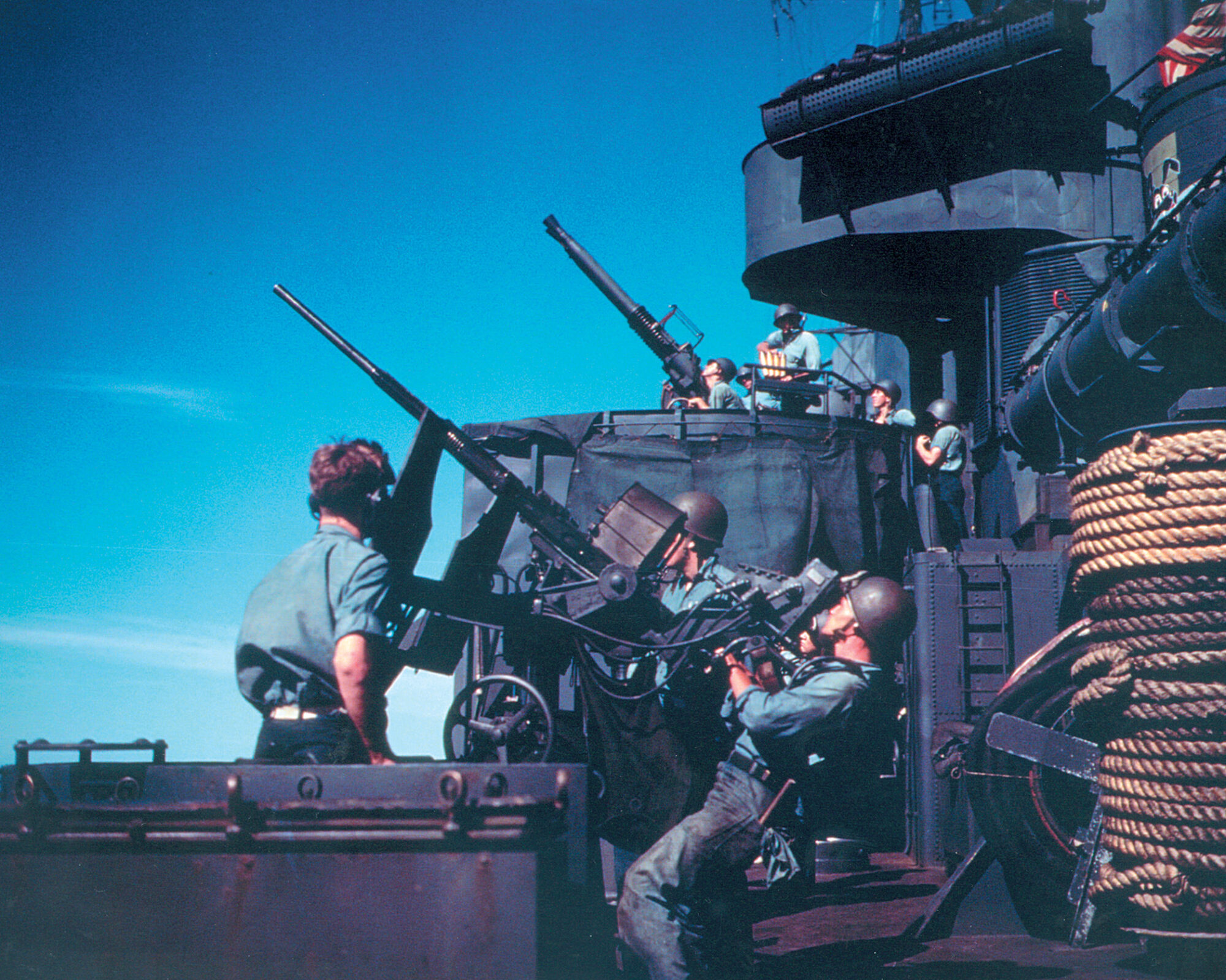

Like his Japanese opponent, Spruance also placed his ships in formations designed to inflict optimum damage. Japanese pilots would first meet an air screen of eager American fliers. Any that survived would have to fly directly through Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee’s frightening battle line of battleships and cruisers, which could pepper the sky with hundreds of antiaircraft shells. Fifteen miles from Lee, three of Spruance’s four task groups prowled the area, arranged in a north-south line with 12 miles separating the units. The fourth steamed between Lee and the three carrier groups. To reach Spruance’s carriers, Japanese pilots would have to elude American fighters, brave Lee’s battle line, and dodge carrier task group antiaircraft fire.

Ozawa opened the Battle of the Philippine Sea at 8:30 am on June 18, when the first of four raids lifted off from his carriers. Sixty-nine fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes winged their way eastward toward Saipan. Instead of wreaking vengeance, they flew unknowingly into one of the biggest air catastrophes of the war for the Japanese. American radar picked up the enemy aircraft 90 minutes later while the Japanese were still 150 miles distant. Within minutes, Hellcat engines roared to life aboard American carriers and planes lifted off at 10:23 to meet the enemy.

Were it not for the seriousness of the situation, the first Japanese raid could almost be described as a comedy of errors. Ozawa, rather than basking in reports of downed American aircraft and sinking enemy ships, listened as a list of mistakes turned the mission into a fiasco. First of all, after lifting off from their carriers, Japanese pilots committed the fatal error of circling and regrouping at 20,000 feet rather than pressing the attack and denying their opponent time to prepare. By wasting these precious moments, the Japanese allowed American Hellcats to establish a multitiered intercept formation miles ahead of Lee’s front line of defense.

The inexperienced Japanese aviators then played right into American hands by charging alone or in small numbers rather than attacking in a coordinated, mass assault, that would have best utilized their formation’s firepower. Once nearing the targets, Japanese pilots often pulled out of their dives too soon or released bombs too quickly in an effort to evade the intense American antiaircraft fire.

A recent innovation helped Spruance’s aviators log an impressive tally of destroyed Japanese aircraft. Fighter-director officers, an addition to the fleet that had been lacking in the war’s earlier days, calmly deployed American fighters at the correct altitudes, speed, and range to intercept the enemy.

In this battle, the fighter-directors received the very capable assistance of Lieutenant (j.g.) Charles A. Sims, an officer aboard the Lexington who spoke fluent Japanese. Sims listened to the Japanese air coordinator as he relayed flight instructions to the aircraft, then passed this information to the American fighter-directors. With this advance knowledge, hundreds of Hellcat pilots confidently rose to meet the enemy. Veteran American pilots enjoyed such a relatively easy mission that one is struck with the number of aviators who shot down two or more Japanese aircraft within seconds.

Not that dangers did not exist. They still faced enemy pilots flying armed aircraft, and even inexperienced pilots could occasionally inflict punishment. Besides, to approach close enough to a Japanese aircraft to register a kill, American pilots had to fly dangerously close to antiaircraft fire from their own battleships and cruisers. An errant move by the pilot, a poorly aimed shell, or simple rotten luck could bring down the wrong plane. The commander of one of the task groups, Rear Admiral John W. Reeves, Jr., was so worried about this situation that he signaled all his ships during this initial raid, “Try to avoid shooting down our own planes. They are our best protection.”

Within a Few Moments of the Battle’s Opening, it Became Evident That a Slaughter was About to Unfold

Admiral Mitscher appeared calm and ready on the bridge of the Lexington. When he heard general quarters sounded at about 9:00, newsman Noel Busch left his room and walked to the bridge. He met a grinning Mitscher, who asked Busch if he were excited at the prospect of witnessing a major battle. When Busch replied he was, Mitscher added, “So am I.”

Aboard the Lexington, Lieutenant Joseph Eggert, Mitscher’s fighter-director officer, commenced the slaughter by barking out the time-worn circus cry for help, “Hey Rube!” Most planes were launched by 10:23, and more than 200 Hellcats raced toward the oncoming enemy.

Busch scanned the horizon and watched the battle drawing closer to him. He first noticed puffs of smoke forming a protective umbrella over a task group in the distance, then observed in fascination as ships at the outer edge of his task group added their fire. In moments, he could hear the gunners firing as a cruiser off his starboard quarter boomed to life, then a symphony of sounds assaulted his ears as antiaircraft and machine guns from his own ship erupted in a raucous response to the enemy planes. One Japanese aircraft tried to sneak closer to the carrier by hugging the water’s surface, but the plane exploded in a fireball and dropped into the ocean a half-mile from Busch.

Within a few moments of the battle’s opening, it became evident that a slaughter was about to unfold. More than half of the Japanese aircraft in the first raid fell to waiting Hellcats before they spotted an American ship. Commander William A. Dean of the Hornet counted almost 25 enemy parachutes floating on the waters below as he raced from spot to spot.

Lieutenant Commander Charles W. Brewer, commander of the Essex’s fighter squadron, engaged the Japanese 55 miles out from his carrier and established a pattern that would be repeated with deadly accuracy throughout the day. Brewer lined up the enemy leader, locked on his tail from 800 feet, and with an accurate burst from his machine guns sent him spinning out of control toward the water. Brewer had barely completed this first kill when he spied a second target close by, aimed, and fired. After downing this second plane, Brewer raced after his third quarry, another Japanese aircraft that ventured close, and quickly dispatched it with another accurate gun burst. A fourth, obviously one of the few experienced airmen still remaining to the Japanese, executed a series of superb loops and maneuvers in an effort to escape Brewer’s guns, but he, too, ended in the water.

Inevitably, some Japanese eluded the American air screen and dove directly at a carrier or cruiser. One dive-bomber approached the Lexington from the starboard beam, but two escorting cruisers unleashed such a thick volume of fire at the solitary plane that to correspondent Busch it appeared as if the lines of fire held the plane for a few seconds like two arms reaching up from the two cruisers. A violent explosion disintegrated the aircraft and ended the danger.

Only a handful of Japanese aircraft survived the air screen and made runs at American ships, most unsuccessfully. A bomb crashed onto the battleship South Dakota, killing 27 men and wounding another 23, and other vessels had to engage in fast maneuvering to avoid attacks, but not one Japanese plane reached its ultimate goal, the American carriers.

The battle proved fast and deadly for the Japanese. Mitscher’s aviators and antiaircraft gunners needed only 34 minutes to decimate Ozawa’s first raid. Mitscher reported little damage to his force, but he could triumphantly relay the information that of the 69 enemy aircraft, all but 27 had been splashed. Elated pilots returned to their carriers and reacted as if they had just visited a carnival shooting gallery. Lt. Cmdr. Paul D. Buie of the Lexington heard one pilot yell to another, “Why, hell. It was just like an old-time turkey shoot down home!” The phrase quickly spread to other ships until everyone spoke of the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. What they did not yet realize was that the turkey shoot had only just begun.

As with the first raid, the second group of Japanese aircraft to take off from Ozawa’s carriers started inauspiciously. The 128 fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes had barely lifted off the decks when one pilot spotted a submarine torpedo churning toward the Japanese carrier Taiho. Without hesitation, Sakio Komatsu veered away from his group and aimed his aircraft toward the path of the torpedo. His suicide dive succeeded when his plane crashed into the weapon, but his sacrifice only earned the hapless carrier a brief respite. The American submarine Albacore remained in the waters and later launched a second torpedo that hit its mark.

The Japanese could not seem to buy a break. Eight aircraft had to return to their carriers because of engine problems, while the remaining 119 flew unexpectedly into a line of fire when they passed Kurita’s van 100 miles out. Kurita’s ships, mistakenly thinking the planes were American, opened a ferocious antiaircraft barrage that downed two of their own aircraft and so damaged eight others that they had to turn back. Before the second raid had even departed Japanese-controlled waters, 19 planes had been lost.

In Less than 30 Minutes American Pilots Took Down Almost 70 Japanese Planes

The situation did not improve for the remainder. American radar picked up the oncoming group at 11:07, only 10 minutes after the first raid had departed. Pilots barely had time to land, refuel, and rearm before again rising to meet the enemy, but their accuracy was just as great as it was in the first raid. Eager pilots charged into the fray, guns blazing from their speeding Hellcats as they cut a swath into the Japanese formations. In under half an hour, American aviators splashed close to 70 Japanese planes.

Lieutenant (j.g.) Stanley Vraciu of the Lexington tallied the largest number of kills this day by downing six enemy aircraft. After dodging the debris from his first victim, a dive- bomber he shot down from close range, Vraciu radioed his carrier, “Don’t see how we can possibly shoot ’em all down. Too many!” Hellcats filled the sky as they grappled with Japanese dive-bombers or torpedo planes. Planes darted in every direction as they either attempted to gain a fix on a target or elude a pursuer, and the American pilots had one thought nagging at them: Antiaircraft bursts from their own cruisers and battleships did not distinguish friend from foe.

Despite the possibility of being shot down by either side, Vraciu turned his Hellcat into the fray and quickly splashed five more dive- bombers. Now low on ammunition, Vraciu headed back to the Lexington, where he almost fell victim to friendly fire. Shouting into his radio that he was an American, Vraciu finally landed his Hellcat after registering six kills in the brief clash. As he stepped away from his aircraft, Vraciu glanced toward Admiral Mitscher on the bridge and held up six fingers to indicate his feat.

Other pilots enjoyed similar successes. Commander David McCampbell of the Essex recorded five kills and logged another probable kill, while a fellow aviator from the same carrier, Ensign C.W. Plant, engaged in such bitter fighting that after he landed back on the Essex, mechanics counted 150 holes in his fighter.

Lieutenant Don Gordon of the Lexington spotted four “Judy” torpedo planes flying one to 15 miles southwest of the battle line at 15,000 feet. Ignoring the handful of Zeros that served as a screen, he pressed his attack against the Judys. He shot down one, then chased the others as they took evasive action. Gordon dipped lower toward the water and splashed his second, then braved American shrapnel and plunged to only 50 feet above the surface. Although he now could barely see through the splashes kicked up by antiaircraft fire, Gordon lined up his third target and dropped him. The fourth Japanese, evidently having seen enough, fled.

Correspondent Busch watched pilots return to the Lexington for more gasoline and ammunition, then rush back into the air to continue the fight. “Indeed,” he later wrote, “from their attitude it would have been reasonable to guess that they were engaged not in a battle at all but in some especially fast and exciting game, like polo or hockey.”

If it was a sporting contest, reporters would have labeled it a lop-sided one, for only 20 Japanese aircraft smashed through the aerial intercept and actually sighted Mitscher’s ships. Fewer still avoided the antiaircraft screen mounted by the carriers to attack different targets. Four, in fact, dove on the Wasp, but adroit maneuvering by the ship’s commander, Captain C.A.F. Sprague, kept the ship out of harm’s way.

The remnants of Ozawa’s second raid headed back after a miserable outing. Ninety-seven of the 128 planes fell to American fire, and the survivors could claim no damage inflicted on the foe.

At least they had located the American fleet, something that most pilots in the third raid could not boast. Forty-seven aircraft launched from Ozawa’s carriers shortly after 10 am, but in yet another display of the pilots’ ineptitude, more than half lost their way and failed to close with Spruance. The embarrassed pilots returned to their carriers without having fired a shot. Of the remainder, a small group did attack three carriers, but inflicted only minor damage while losing seven aircraft. A frustrated Ozawa saw three raids wing toward the enemy and accomplish nothing. All he could do was hope the fourth and final raid made amends.

It did not. Almost 50 of the 82 aircraft in this final attempt failed to spot the American force and continued toward friendly airfields on Guam. Unfortunately, American Hellcats pounced on the Japanese as soon as they approached the airfield, sending 30 Japanese airplanes spiraling to a fiery demise.

A handful of Japanese aviators stalked the carrier Wasp and swooped down in an attack. The capable Captain Sprague ordered hard rights and lefts to avoid the bombs, and as a result suffered no more than nuisance damage caused by shrapnel.

Barely a hundred of Ozawa’s 374 aircraft limped home to their carriers by the end of that devastating morning. Spruance’s airmen had delivered another stunning blow to enemy air power, a punch from which the Japanese Navy never quite recovered. The carriers steamed back to Japan where, bereft of their air arms, they served the remainder of the war in a secondary capacity. Against this tremendous loss, Spruance counted the comparatively light damage of 22 downed airplanes and 60 men killed.

Ozawa’s humiliating day did not end with the four raids, however. Mitscher’s airmen inflicted grave damage, but on top of that, American submarine commanders added a frightening toll of their own. Japanese pilot Komatsu’s suicidal dive momentarily saved the Taiho from the Albacore’s first torpedo, but his heroic action failed in the long run as five other torpedoes churned their way toward Ozawa’s flagship, one of which smacked into the Taiho’s starboard side around 9:15.

More than 1,200 men died with the Shokaku

The crew worked frantically to save the carrier by pumping unrefined and highly flammable oil overboard before a spark ignited the material. Just when it appeared that the Japanese might have made headway, another of those frustrating errors occurred that made this day a disaster. One of the ship’s officers opened the ventilating ducts in hopes of removing the fumes, but his action instead spread the dangerous vapors throughout the carrier. At 3:32 pm a spark ignited the fumes. The ensuing eruption ripped out both sides of the ship’s hangar, warped the deck, and tore huge holes in the carrier’s hull. Ozawa and his staff had enough time to switch his command to a rescuing destroyer, but 1,500 men went down with the stricken Taiho.

The American submarines were not finished. Commander Herman J. Kossler of Cavalla spotted the Shokaku at 11:52, deftly moved into attack position, and sent a spread of six torpedoes rushing toward the carrier. Two missed, but the other four rammed directly into the veteran of Pearl Harbor. The Japanese crew worked for more than four hours to save the carrier, but additional explosions caused by fire doomed the ship. More than 1,200 men died with the Shokaku.

The Americans had delivered a powerful one-two punch to the Japanese. Many aviators in the force now hoped that Admiral Spruance would allow them to launch a third blow that might catch Ozawa in a crippled condition and finish him off. Still worried about a possible end run by the enemy, and also concerned that his weary aviators were in no shape to embark on yet another mission, Spruance maintained the easterly course off Saipan rather than chasing after the Japanese.

At 10 pm on June 19, now convinced Saipan was safe from an end run, Spruance reversed course and headed to the west so his aircraft could launch a dawn air search to find Ozawa. Pilots scoured the ocean most of the day on June 20, but had no luck until 4 pm, when an Enterprise aircraft located the Japanese 275 miles from Mitscher’s carriers. Anxiety mixed with jubilation aboard the American ships. Men reveled in the knowledge that they had located the Japanese, but also realized that Ozawa stood at the maximum range for American fighters.

With no more than three hours of daylight remaining they would barely have enough time to fly out, hopefully locate the targets where expected, mount the attack, and fly back to their carriers before darkness or empty fuel tanks made the mission even more perilous. One of Mitscher’s staff members told the commander that he risked losing a large number of aircraft if he launched at this late time.

Weighing the risks with the possibility of knocking the Japanese Navy out of the war as an effective fighting force, Mitscher concluded that he had to accept the hazards. The launch order went out at 4:10, which sent aviators scurrying out of their ready rooms, and within 20 minutes more than 200 fighters, dive- bombers, and torpedo planes raced toward Ozawa.

Pilots kept a wary eye on their fuel gauges, as they knew how close this one would be. One gunner jumped into his dive-bomber aboard the Lexington and noticed the crew giving him a thumbs-up signal. “Thumbs up, hell!” he thought. “What they mean is, ‘So long, sucker!’” Some men from the Cabot doubted whether any of their aircraft would return.

Lieutenant Commander James Ramage, commander of the Enterprise’s Bombing Squadron 10, lifted off the carrier at 4:30 and headed west. As he approached 15,000 feet, he smelled smoke and asked his gunner if he was smoking a cigarette. The man replied in the negative, but in seconds thick, black smoke filled the cockpit. Not wanting to miss out on the carrier attack, Ramage flew on, hoping that spilled lubricating oil caused the smoke. In five minutes the smoke dissipated.

Ramage and the rest of the pilots faced a larger concern a few minutes later when Mitscher notified them of an error in the original sighting. Rather than being where expected, Ozawa’s carriers actually stood 60 miles farther away. Like the other aviators, Ramage would have to conserve as much gas as possible for the attack and return home. For the first time, many fliers concluded they could not possibly have enough fuel to make it back to their carriers, necessitating a hazardous splash landing at sea.

The pilots received confirmation of their worries as they winged west. One by one, pilots noticed their fuel gauges dipping below the halfway point, and they had not even sighted the enemy yet. The initial traces of darkness crept over the horizon, meaning that if they could not find Ozawa within 20 minutes, he and his ships would simply disappear into the night.

Then, as hopes began fading, Ozawa’s ships appeared not far away. The Americans made the most of their limited time. Ramage spotted a carrier and rolled into his dive, ignoring the wall of Japanese fighters that hoped to intercept him. He recalled that he heard his plane’s machine guns open, “then I looked over to the right and within five feet of me, passing below, was a Zero.”

“Skipper, Look Back. She’s Burning From Asshole to Appetite!”

At 5,000 feet Ramage opened fire with his two .50-caliber machine guns. He watched the stream of tracer bullets hit the carrier’s forward elevator, then at 1,800 feet released his torpedo. Ramage yanked the airplane back at 300 feet as thick enemy antiaircraft fire from nearby battleships, cruisers, and destroyers enveloped him. He wondered whether he had inflicted any damage to the carrier. His gunner yelled confirmation that the torpedo had struck its mark. “Skipper, look back. She’s burning from asshole to appetite!” Ramage was too occupied in maneuvering the aircraft through the enemy fire to look back. Of more concern was the encroaching darkness.

Lieutenant Tom Bronn of the Lexington turned his Avenger into a dive at 9,500 feet. As multicolored shellbursts exploded on all sides, he aimed for a carrier, flew straight toward it, dropped his four bombs at 2,500 feet, then veered away and scoured the skies for the best way out of the shooting. As he departed, he thought that three of his four bombs smacked into the carrier.

Bronn and his cohorts left a scene of devastation. They shot down 65 Japanese aircraft, sank the light carrier Hiyo and three other ships, and damaged two carriers and two cruisers against the loss of 18 planes. One of Ozawa’s demoralized officers wrote in the flag log that of the 430 aircraft with which Ozawa began the day’s fighting, “Surviving carrier air power: 35 operational aircraft.”

The American aviators had been through a frantic attack, but now they faced another danger: the return in the dark to their carriers 250 miles away. Bronn had begun his dive as the sun was setting to the west, and by the time he had selected his course for home, darkness surrounded him. He remained at a low altitude and altered course several times as he weaved through the Japanese ships to avoid their fire, tactics he knew used precious gas, but he could not worry about returning to his ship until he had exited Japanese-controlled space. At least he knew the twilight made it harder for Japanese gunners to spot him.

Nearby, a Zero approached Lieutenant Gordon’s aircraft from above and closed to within 500 feet. Gordon quickly looped into an upside down overhead and fired a burst at 200 feet that caught the enemy craft head on. Gordon then gunned his engines, sped through the disintegrating Zero, and headed for home.

Bronn, Gordon, and the other exhausted pilots commenced a two-hour return flight to carriers that, by the time the planes arrived, would be almost indiscernible in the darkness. As they flew on, the steady drone and rhythm of the engine had an almost hypnotic effect on the fliers, who battled weariness and fear. One by one, aircraft suddenly dropped to lower altitudes, sputtered out of fuel, then gradually swooned toward the sea. Pilots near the tail end of the returning aircraft could see a string of phosphorescent marks, telltale signs of splashdowns, dot the water along the route back to Mitscher’s carriers.

Correspondent Busch waited along with Mitscher for the planes to return, a time they found intolerable. “The interval of four hours or so,” he later wrote, “between the time the planes took off and the time they began to return was, on our carrier, a period of suspense even more intense and unrelieved than the periods waiting in yesterday’s battle.”

Always thinking of the safety of his aviators, Mitscher prepared a welcome he knew they would appreciate. To give his carriers sufficient maneuvering room to land planes or rescue downed aviators, he spread out his task groups so that 15 miles separated each. He then risked being spotted by Japanese submarines by ordering his ships to turn on all their lights so the aviators could easily spot, and then more quickly land on, the carriers. Five-inch guns on destroyers and cruisers boomed star shells into the skies for greater illumination, while carrier searchlights beamed directly upward.

Mitscher’s orders energized the tired pilots, for they knew their commander did everything possible to make their return safer. Lt. Cmdr. Winston recalled the effect aboard the Cabot when the lights flashed on. He said the men “stood open mouthed for the sheer audacity of asking the Japs to come and get us. Then a spontaneous cheer went up. To hell with the Japs around us. Our pilots were not to be expendable.”

The next two hours saw a steady string of aircraft sputter to nerve-wracking landings aboard the first carrier they spotted. If they lacked enough fuel to reach a carrier, they splashed as close as possible to an American destroyer or cruiser so they could be rapidly picked up. Some aviators, frantic to land safely, cut in on other aviators attempting an approach to the same carrier, or they disregarded wave-offs from carrier personnel. Nearly half of the aircraft landed on ships other than their own.

Many made it without injury. Ramage, who had earlier gone over the ditching procedure with his crew, spotted his formation in the eerie glow below and commenced his approach. Suddenly, the Enterprise radioed him that a plane had crashed on landing and that he must find some other carrier. Fortunately, Ramage soon spotted a large carrier two miles away upon which he landed.

Aboard the Lexington, correspondent Busch watched one plane come in too high. The aviator missed the cables and crashed into a parked aircraft. His propeller killed a deck hand and the rear seat gunner in the plane that had only moments before set down from its own hazardous journey. Lieutenant M.M. Tomme landed his plane on the Yorktown, but before he climbed out of his cockpit the plane behind him came in too fast, bounced off the landing deck, and smacked directly on top of Tomme’s aircraft, killing him.

“Chances Are That It [the Japanese Fleet] Will Never Emerge Again as a Fighting Force in This War”

Despite these incidents, Mitscher’s illumination helped save most of his pilots. Eighty aircraft were lost because of low fuel or hazardous landing attempts, but American ships quickly retrieved most of their crews. Fifty aviators either died in the landings or were lost at sea.

Admiral Spruance completed the Battle of the Philippine Sea over the next three days. On June 21 he sent Lee’s battleships and cruisers to the west in hopes of catching up to the retreating Ozawa, but Lee failed to locate his quarry. Two days later, with no seaward threat remaining to the Saipan ground assault, Spruance sent most of his ships back to Eniwetok for repairs and resupply.

Controversy quickly erupted over whether Spruance had acted wisely in retaining his carriers close to Saipan instead of giving them free rein to head out for Ozawa. “The enemy had escaped,” Mitscher wrote in a battle report that accurately conveyed how most naval aviators felt. “He had been badly hurt by one aggressive carrier strike at the one time when he was within range. His fleet was not sunk.”

Others disagreed. Ozawa steamed out of Tawi Tawi with the intention of destroying Spruance’s fleet. Instead, the Japanese admiral returned without a viable air arm and without three carriers, while Spruance still commanded the mightiest conglomeration of ships in the war. Spruance gambled by sitting off Saipan and letting Ozawa come to him, but the results proved his move was correct.

A contemporary of Spruance’s, correspondent Busch, stated as much at the time. He compared it in importance to the classic World War I naval Battle of Jutland, and wrote, “Chances are that it [the Japanese fleet] will never emerge again as a fighting force in this war; its absence from the South Pacific will give General MacArthur a clear field there.” His declaration was mirrored 40 years later when historian John Costello wrote that the turn of events would “prove that the victory Spruance had won in the Battle of the Philippine Sea was one of the most complete of the whole Pacific War.”

Had Spruance needed confirmation that what he had done was proper, and Spruance rarely concerned himself with what other people thought, the words of his superior would have sufficed. Admiral Ernest King, the Chief of Naval Operations, visited Spruance at Saipan the following month. He went out of his way to tell his subordinate, “Spruance, you did a damn fine job there. No matter what other people tell you, your decision to remain near Saipan rather than chase after Ozawa’s carriers was correct.”

John Wukovits is an expert on the naval war in the Pacific. He is also the author of Devotion To Duty, a biography of Admiral Clifton A.F. Sprague.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments