By Eric Niderost

Donald L. Versaw joined the U.S. Marine Corps on Armistice Day, November 11, 1939. After basic training and a stint in the Marine Corps Operating Base Band in San Diego, he was sent overseas to join the Fourth Marines Band in Shanghai. Versaw arrived in China in the summer of 1940, when Japan’s aggressive moves in Asia had already brought it on a collision course with the United States.

The Fourth Marines had been stationed in China since 1927, guarding American lives and property at a time when China was experiencing social and political turmoil. Their mission was something of an anomaly at the time—a regiment of leathernecks not serving aboard U.S. naval vessels or guarding U.S. embassies, but patrolling one of the great cities of the world, a place that was a legend in its own time.

The Marines’ mission became more delicate after the Japanese Army took over greater Shanghai in 1937. The Fourth Marines helped defend the International Settlement, an enclave that was largely run by Anglo-American interests. The Japanese, much to their frustration, had to leave the Settlement alone … at least until Pearl Harbor.

The Marines handled the situation with a combination of strength, diplomacy, and tact. The Japanese were constantly testing, probing, searching for weaknesses in a deadly game of political and military cat and mouse. Several confrontations occurred between Marines and Japanese soldiers, little reported at the time, which could have led to war as early as 1937. The Fourth Marines did a magnificent job, but the unit was withdrawn in November 1941. Their position was untenable; if the Japanese had invaded the Settlement, the roughly 800 Marines could have done little against 300,000 Japanese troops.

The Fourth Marines were pulled out of Shanghai and reached the Philippines just days before the war began. After Pearl Harbor, Versaw and other bandsmen traded musical instruments for rifles. He became a member of E Company, Second Battalion, Fourth Regiment. The Fourth was eventually transferred to the island of Corregidor in Manila Bay.

Versaw and his fellow Marines endured the terrible siege of Corregidor only to suffer an even crueler fate when the island fortress surrendered in May 1942. Then, Versaw began a harrowing 40-month ordeal as a prisoner of the Japanese, both in the Philippines and in Japan. In July 1944, he was transferred to Japan aboard one of the infamous “hell ships.” Thereafter, he became a forced laborer in the Nittetsu-Futase Tonko Kaisha (coal mine company) on the island of Kyushu, suffering the cruelties and privations that were so common for those unfortunate enough to fall into the hands of the Japanese.

After repatriation, Versaw served in Korea as a member of a photo unit with the 1st Marine Division. After his retirement from the Corps, he worked in the aerospace industry on the NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) Apollo and Saturn programs. Today, he lives in Southern California and is active in several POW organizations.

First, a little background. When were you born, and where?

DV: I was born on June 23, 1921, at home in Bloomington, Nebraska. Father had very little of his own land. Mostly he worked land belonging to others who were unable to do farm work. He used a team of horses on a share basis. The most common crops were corn, wheat, and oats. On his own ground he raised sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes, and sometimes melons and squash.

I think the effects of the Depression were probably universal and affected people in all walks of life in varying degrees, depending on the circumstances. People who did farm work benefited more than people who lived in cities, because in cities there was little opportunity to grow things to feed their families. The Depression era also coincided with a drought, which was devastating.

Why did you join the U.S. Marine Corps?

DV: I joined the Marine Corps hoping to become a Marine musician, acquire experience, and save money in order to go back to college. I was quite small and youthful in appearance, boyish, really, and had little chance competing with the many older jobless men in the work- place.

You already played an instrument in school?

DV: I had been a better than average music student since the eighth grade and learned to play an alto horn belonging to the school. My sister purchased a bass Mellophone, a French Army issue and relic of World War I. I played it during my last two years in high school and one year in college.

“Stealing One’s Sweetheart or Shack Mistress Happened Sometimes, Particularly on Foreign Assignments.”

How were recruits chosen for band duty?

DV: Those selected to serve as musicians in the Marines had to bring their skills with them. It was one of the few occupational specialties that required prior acceptable ability at the outset. The usual way that Marines were chosen for band duty was by auditions.

The old pre-World War II Marine Corps had an almost legendary quality that resonates even today. What was the old Corps really like?

DV: Likely there was not much difference between prewar Marines and those afterward as the ‘legend’ would have it. It was a smaller Marine Corps that was managed at the top by a few World War I veterans but run by old staff non-coms who often delegated their authority to second-term corporals and sergeants. The level of education was generally below the high school level. Drug abuse was not a problem, but alcohol and tobacco were. It was a time of great mutual respect among the troops. Stealing one’s sweetheart or shack mistress happened sometimes, particularly on foreign assignments. Sunburn and venereal disease were court-martial offenses.

When did you sail for Shanghai?

DV: I was ordered to Shanghai at the end of May 1940, and went aboard the USS Chaumont, one of two Navy transports in San Diego. The ship called at all ports where Navy and Marine units were deployed—San Pedro, Mare Island, Fort Mason, Pearl Harbor, Wake Island, Guam, Midway Island, Manila, and finally Shanghai sometime during the month of August. It was truly the original slow boat to China.

In the 1930s and 1940s Shanghai was something of a legend in its own time, vice ridden and corrupt, yet also China’s most modern, progressive city. What were your impressions?

DV: In terms of population, Shanghai seemed to burst at its seams the whole time I was there. Of course, refugees from the fighting in Japan’s war with China were the major cause. The International Settlement was a haven for refugees from all over the world, including Russians [White Czarist Russians] and more recently those from the war in Western Europe [Jews]. The city was neat and managed as well as could be under the circumstances. I felt comfortable in this amazing city where I could met all my needs with even less than the $21 a month we were given.

Shanghai was the most desirable duty station because of the exchange rate of U.S.-Chinese money. This increased the purchasing power of the lowest paid ranks to a much higher level. Goods and services in the local market were less costly and more available. There were roller rinks, tennis and handball courts, and great places to eat like Sunya’s and Jimmy’s Kitchen. [The latter was run by an American ex-serviceman.]

What was your life like as a bandsman?

DV: The band was quartered in Billet Williams on Ferry Road where the PX (post exchange) was located and the headquarters company offices. There were no messing facilities at that location, so we either walked or hired rickshaws to eat at the headquarters mess hall. Rehearsals were held every weekday morning. If parades or practice parades were scheduled, we went into formation and marched through the city streets to the parks.

Shanghai’s International Settlement was by then the “lonely island,” surrounded by Japanese-occupied territory. There were several incidents involving Marines and Japanese. The foreign military contingents, largely British and American, went on alert on one occasion in July 1940, due to the tensions. What do you remember about this tense time?

DV: My arrival in August 1940 was after the alert, but precautionary barricades and procedures were still being followed. As a bandsman, I made no patrols, but the MP company and the battalions made security runs and inspections. I didn’t see the action myself, but there was an incident with “Chesty” Puller some time before that was still the talk of the regiment. Japanese soldiers were attacking the sampans tied up on our [International Settlement] side of Soochow [Suzhou] Creek. They were busy abusing the Chinese living on the boats and chopping holes in the hulls. Chesty took a dim view of this and ran them off with a Marine squad. It was said he almost started World War II doing that!

Shanghai was also seething with spies and agents of both the Japanese and Chaing Kai-shek’s Nationalist government. Acts of terror were common, including bombings, kidnappings, and murder. Did you see any of this?

DV: The presence of terrorists was always apparent. The new car agency adjacent to the Fourth Marines Club was bombed soon after I came on station. We sometimes encountered dead and mutilated bodies when going to morning mess. Once there was a cardboard box on the street containing two severed human heads. There was still an expression of fear on their faces.

“The Base was Attacked by a Flight of Japanese Bombers. Most of the Bombs Fell on the Barrio [Native Quarter], and the Marines Suffered Our First Casualties.”

The Fourth Marines were finally withdrawn in late November 1941, only a few days before the outbreak of war. Unfortunately, at least in retrospect, the regiment sailed to the Philippines, not the United States. How did you feel about the redeployment?

DV: As the SS President Harrison raised anchor and moved down the Whangpoo [today the Huangpu River] in late afternoon, it was such a dramatic sight—taking a last look at that dramatic waterfront skyline. Rain clouds lingered in the west in such an array as to create shafts of light shining down upon the magnificent old city. It was a dramatic and moving experience I’ll never forget.

The Fourth Marines arrived safely in the Philippines, but shortly thereafter Pearl Harbor was attacked and the U.S. was at war. At the time, the Fourth Regiment was stationed at Olongapo, on the island of Luzon. What was this posting like?

DV: Olongapo was an old, well-established naval station —lots of palm trees and expanses of green grass along well-maintained roads and streets. The base was attacked by a flight of Japanese bombers. Most of the bombs fell on the barrio [native quarter], and the Marines suffered our first casualties. A few days later, while [I was] standing guard at the old coaling docks, a flight of Japanese planes followed our PBY aircraft returning from patrol and attacked them sitting on the water. They caught me literally with my pants down. It was more frightening than embarrassing, and the experience left me feeling that going to the head [toilet] would be the most likely time for the enemy to strike!

Eventually, the Fourth Regiment was transferred to Corregidor, the island fortress in Manila Bay.

DV: At first I thought it was a real break for us to be sent to Corregidor. I heard it was armed to the teeth and protected by a great minefield. The day after I arrived, December 29, 1941, the island suffered the first of many air raids. I took shelter in a ditch on the side of a dirt road. From my location I couldn’t see the enemy planes. Bombs began to fall, and small planes began to strafe the built-up areas above me.

The attack continued seemingly forever. After the “all clear” was sounded, I got up, and when I looked back I noted the ground was wet, outlined in sweat from my shaken body. When I went back to the barracks, my stuff was just about where I had left it, but it was all covered in cement and plaster dust. There were great holes in the ceiling of the so-called “bomb proof” million dollar barracks!

As the siege dragged on, conditions deteriorated, didn’t they?

DV: Rations were cut in half sometime during the month of January 1942, and it went downhill after that. Near my position was the field kitchen for H and E Companies on the South Shore Road. Sergeant Harmon cooked cereal such as oats, corn, or wheat and served it with a squirt or two of canned milk. To give hungry men only a taste of something seemed to me a cruel tease. Yes, we did get a slab of horse or mule meat once or twice. It was very coarse and tough and tasted wild, but it was meat. By the end of April, the rations were so small they barely made our mess kits wet.

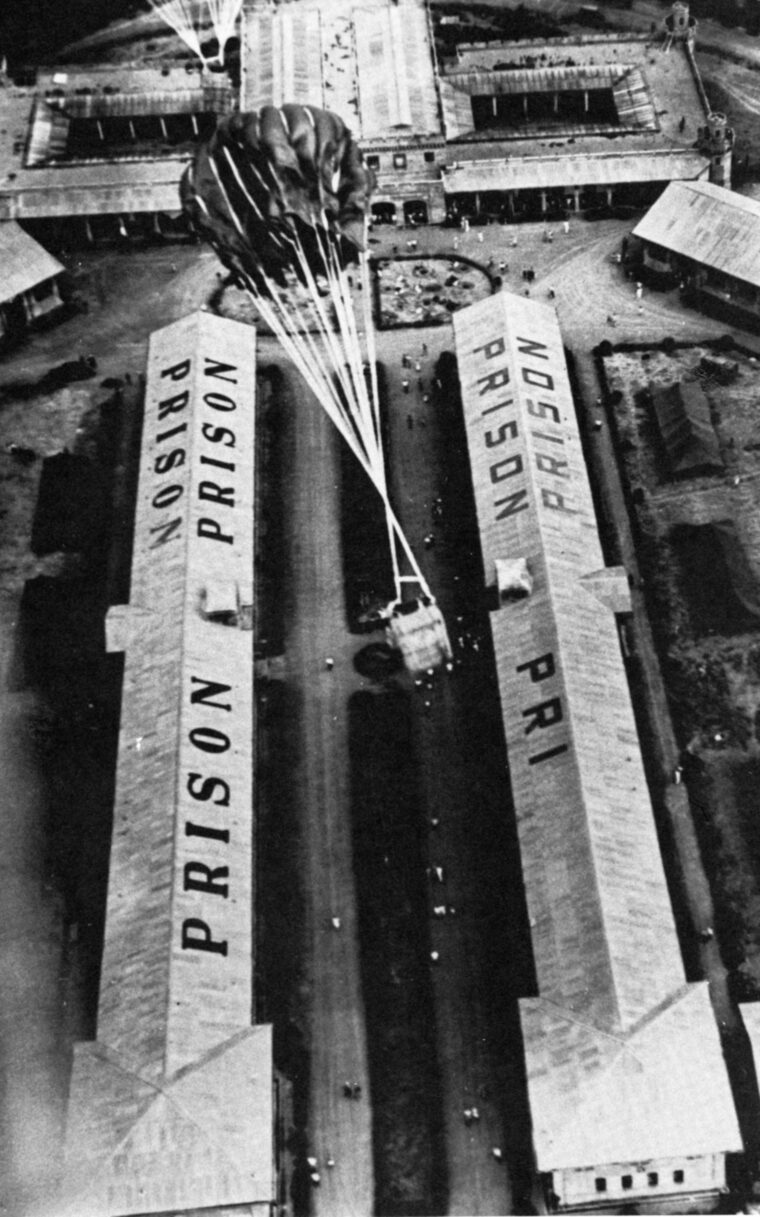

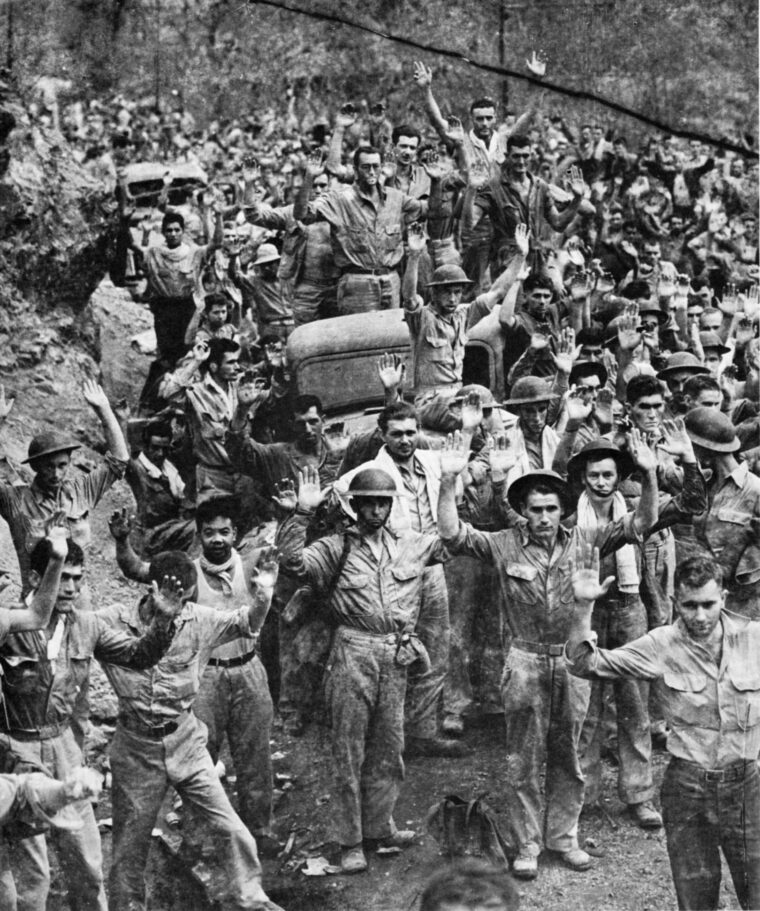

Corregidor was forced to surrender in May 1942, ending organized American resistance in the Philippines. After surrender, the garrison stayed on the island for a time before being transferred to camps on Luzon. On the way to the POW camps, American soldiers and Marines were paraded through Manila to advertise the Japanese triumph to the Filipinos. What do you remember of that experience?

DV: The March of Shame it was called, from Paranaque Beach to Bilibid prison. I was there and made the march. Compared to the Bataan Death March, however, it was Mardi Gras. Oh, we were a motley looking mess. The purpose of it [the march] was to lower the prestige of the white man in the Philippines. I don’t think it worked very well. Filipino groups along the line of march came out to serve water from tubs with the best tea cups. They also distributed rolls, cookies, and rice with bits of fish and shrimp wrapped in banana leaves. The Japanese guards tried to discourage them and ran them off the street in a few places.

“I Scrambled Down the Ladder Into the Hold Only to Find That it was Already Crammed Full, as Far as I Could See, with Half-Naked, Sweating Men in Ragged Beige-Colored Tatters.”

Much of your time in the Philippines was spent at Clark Field, where Japanese brutality was common. What happened there?

DV: I witnessed the punishment of the senior American POW, an Army captain by the name of Fleming. We all had to remain out in the blazing sun without canteens or water bottles for hours, but the worst part was to see our POW commander beaten while being tied to a post. Occasionally, a prisoner was beaten at the gates if he was discovered trying to bring in “contraband” like extra food.

The effects of malnutrition were evident at Clark, as they were in other camps, in the late weeks of 1942. First, it was the pellagra, perhaps aggravated by so much exposure to sunlight but also due to lack of B vitamins. That was followed by dry beri-beri, which we called sore and aching feet. We also had a sudden outbreak of eye ulcers. Had it not been for the distribution of International Red Cross packages, it would have been a greater disaster for us.

After about two years as a prisoner in the Philippines, you were transferred to Japan via one of those infamous hell ships with hundreds of men stuffed into cargo holds with little food or water for days on end. What do you recall about this experience?

DV: The 17-day voyage to Japan from Manila, in July 1944, was indeed the worst experience of captivity. The ship was the Nissyo Maru, a rusty-red, mottled transport. I scrambled down the ladder into the hold only to find that it was already crammed full, as far as I could see, with half-naked, sweating men in ragged beige-colored tatters. Nearly 700 men had already entered the hold before me. Behind were another 800 men to come.

As the newcomers jammed into the hold, those who had already been there 40 minutes, 30 minutes, 20 minutes began to drop. They were fainting. By midday, with a tropical sun, it was like being in a giant steam iron. There were no latrines—just a tub that filled sometimes to overflowing. There was a mess around the tub that was beyond description. There were 1,600 prisoners aboard. Finally, we were divided into roughly two groups. The larger group was confined into the forward hold. The Nissyo Maru arrived at the port of Moji, Kyushu, on August 3, 1944.

You were then put to work as a slave laborer in the Nittetsu-Futase Tonko Kaisha (coal mine company) on the Japanese home island of Kyushu. How difficult were the circumstances?

DV: I was first sent to work in a mine that was very deep underground. I believe I had the night shift. I wore a cap with a fiber board receptacle for the miner’s lamp. My clothes consisted of a pair of very thin cotton shorts and a shirt with no buttons, just ties. I was issued one pair of rice straw sandals, but they didn’t last the first night. After that, I went barefoot until B-29s [Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers] dropped clothing to us immediately after the war. I also carried my issue “ebu” [short-handled hoe] and “kakita” [basket with half-open side.] During the winter, personal hygiene became a problem. Our tatami mats became infested with fleas and our clothes with lice. These conditions persisted until insecticide powder was dropped to us at the end of hostilities.

Was there any attempt by the POWs to sabotage mine operations?

DV: That was something that each prisoner or small groups of prisoners dealt with when possible. When possible everyone did little things that helped curtail the enemy’s war effort. But to do something on a significant scale might well mean there would be less food and less heat and increased privation. Yet, some cars that were supposed to contain only coal went out of the mines with a great deal of rock underneath. No matter how small the effort, it left us with a feeling we were still in there trying to help our country.

After liberation, you continued to serve in the Marine Corps, then later had a successful career in the aerospace industry. But in recent years there has been controversy over how the current Japanese government has done little or nothing to acknowledge Japanese war crimes and atrocities of the past. What is your perspective on that issue?

DV: American POWs got nothing back except back pay and ration money. Moreover, they were denied rights to sue Japanese companies for compensation—companies that used them for slave labor. I don’t understand how our rights were bargained away by diplomats. I fault our own American government for that. The current Japanese government should exercise the compassion they are famous for and apologize for the excesses of the past. It would not hurt them to do that.

It behooves you to get Mr. Versaw’s name correct in the title.

I was a friend of his.