By Maura B. Delaney

Letters were a valuable commodity to the World War II soldier. They were the link to home and to all things familiar in a most unfamiliar place and time. The war produced mountains of mail. In 1943, GI’s received an average of 14 pieces of mail per week. On the island of New Guinea in the Pacific, three-quarters of the soldiers wrote one or more letters every day. While acknowledging the value mail held as a stabilizing factor in a soldier’s psychological well-being, the U.S. government was also grappling with two major concerns regarding the mail system, volume and content. Volume was directly linked to critical shipping space needed by the armed services.

Victory Mail

In response to the volume issue, the U.S. government created “Victory Mail” or “V-Mail.” These letters were microfilmed versions of full- size sheets. The condensed letters were an effort to speed the delivery time and allow for more room in overseas shipping. Every 150,000 letters scanned would result in one ton of shipping space saved. This concept began in England as “airgraphs” and was picked up in the United States on June 15, 1942. The U.S. Army began operating a large V-Mail facility at Casablanca in North Africa in April 1943. Over a billion letters were sent via V-Mail between 1942 and 1945. Miniaturized V-Mail reduced 2,575 pounds of regular mail to a single sack weighing 45 pounds.

One 16mm roll of the microfilmed V-Mail letters weighed in at seven ounces and could hold more than 1,500 letters. A large reel could contain upward of 18,000 letters. Numerous advertisements were produced promoting the use of V-Mail. These included such slogans as “The Next Best Thing to a Leave Is a Letter.” Others said, “Write that boy in service today!” and “Let a 300-mile-an-hour mailman speed your letter overseas.”

The second concern regarding mail was censorship of content. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, recognizing the potential breach in military classified information that existed within all aspects of communication, established the Office of Censorship in 1941. The office employed 14,462 civilians to monitor communications between the United States and other nations.

The letters and a journal of this author’s uncle, Corporal James G. Delaney, a military transport flier, provide a glimpse into daily life in the armed forces during World War II while also offering some understanding of the censorship that occurred. The comparison of the journal entries and corresponding letters written the same week also reveals a level of self- imposed censorship.

One of 319 Casualties

Growing up, I knew little about my Uncle Jimmie, who died before I was born. When I was a child, my father told me that Jimmie was killed by “friendly fire” while serving in World War II. I learned only recently that he was one of 319 casualties, shot down on July 11, 1943, during Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. This incident has become known as one of the most tragic incidents of friendly fire during the entire war. I knew little else, except that his death, as told to me by my mother, altered my grandmother’s life forever.

Rose Delaney, who had battled rheumatoid arthritis for a number of years, would rarely walk again after hearing the news of Jimmie’s death. That was it. There were never any more stories forthcoming from my father about his older brother. So, Jimmie’s story, shrouded, I imagine, in too much pain, went untold until it resurfaced some 15 years ago, when my sister Roseann and I came across a simple brown envelope upon which was written “Jimmie’s Letters. Do Not Destroy.”

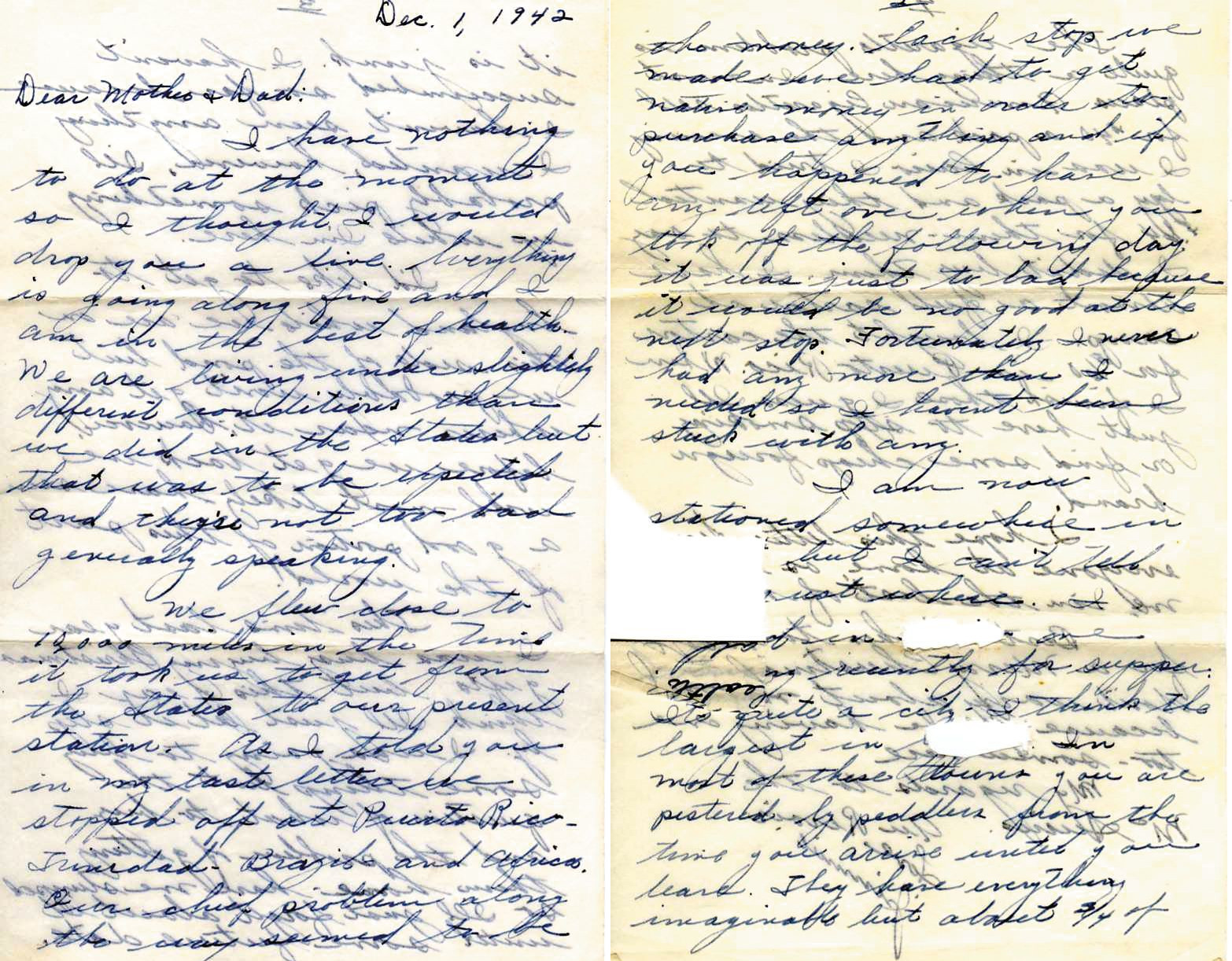

Opening the envelope, we found 25 letters and a 1943 daily journal, all in Jimmie’s hand, all written from North Africa. The letters spanned several months from November 13, 1942, to July 4, 1943, and the journal from January 1 to July 8, 1943. The letters were given to my nephew, Patrick Connell McNulty, and I was given the journal. In August of 2005, I finally took the time to read the letters, and I was fully introduced to Jimmie, one letter at a time.

These letters and journal entries are so conversational in style that I actually felt like he was talking to me through the pages. These newfound words penned by my uncle gave shape to a life and piqued my curiosity, inspiring me to research not only the Delaney family genealogy, but also the archives of the city of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where he lived, his military records, and countless declassified documents of Operation Husky.

War Comes to the Wyoming Valley

Born November 13, 1912, Jimmie seemed to live an ordinary childhood, certainly no different from those of his siblings in Wilkes-Barre in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, the only thing that sets this otherwise ordinary life apart from the others is World War II and a fateful mission over the shores of Sicily in July 1943.

There are no records of Jimmie’s elementary school years. His high school years, however, were filled with diverse activities. He attended Coughlin High School, where he would later teach. He was president of the glee club for two years, lettered in track his senior year, and performed in the Coughlin Collegiate Minstrels. He entered St. Thomas College, now Scranton University, in Scranton, Pennsylvania, where he managed the Science Class intramural basketball team, and continued his acting in local theater and the St. John’s Dramatic Club. He graduated in 1935 with his bachelor of science degree. He eventually became a high school chemistry and general science teacher, but not before trying his hand at aeronautics as an employee of the Brewster Aircraft Plant, Long Island City, New York.

On December 8, 1941, the Wilkes-Barre Record ran the following headline: “It was a transformation of but seconds to turn a quiet home-loving and Sabbath-observing Valley into one of intense patriotic action.” This was, of course, in response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the day before. Although it is said that the paper used its share of hyperbole in this headline, it is fair also to say that the Wyoming Valley World War II experience became that of the nation. Pamphlets explaining what to do in an air raid and open discussions of potential bomb shelter sites dominated local news reports. At this time, Jimmie was living with his parents and two of his seven siblings.

As a high school teacher, it seems likely that Jimmie would have had ample opportunity to engage his students in discussions about the attack on Pearl Harbor, patriotism, and the impact the war was having in their homes. He and his students read reports about people in the city making purchases of sugar and flour at staggering rates. This rush on purchases was likened to hoarding and solicited a response from local grocery store owners to limit sales while restaurants and hotels dealt with this growing anxiety by removing all sugar bowls from the tables.

Jimmie Enlists

“Just in Case,” and his family believes this photo is the last taken of him.

The anxiety was matched only by the valley’s growing patriotism. By January 1942, men in the Wyoming Valley were breaking all the recruitment records set during World War I. One such enlistment story is that 60 Hanover Township High School seniors, including the entire football team, volunteered for service. As most were under the age of 18, they were not allowed to enroll, but the act itself was not lost on the people of the valley. This was a time to serve. So, on March 19, 1942, Jimmie and three of his brothers—Frank, Joe, and my father, Tommy—enlisted. Because of prior debilitating injuries or marital status, three of the brothers were denied enrollment. Jimmie was the only family member who would be allowed to serve.

Jimmie was assigned to the 316th Troop Carrier Group, 45th Squadron. He was accepted into the Air Corps Radio School and graduated as a radio technician on September 7, 1942. While stateside, he was assigned to a number of bases, including Keesler Field, Mississippi; Scott Field, Illinois; Larson Field, Fort Benning, Georgia; and finally Del Valle Air Base, Austin, Texas. On November 11, 1942, while stationed at Del Valle, Jimmie received orders that his squadron was shipping out. Before departing he called home and followed up with a letter to his parents on November 13, 1942. It read in part, “Dear Mother and Dad: We should be leaving here sometime today [sic] we make—one more stop in Florida and then we will probably only be in Florida for a few days and most likely will be well on our way by the time you receive this letter. What our destination is I can’t say because we haven’t been told. It will probably be South America, Brazil or one of those places.”

He continued later in the letter to encourage his mother not to worry by saying, “This letter merely indicates a change of address —nothing more” and to “Keep your chin up darling and I will write you as often as possible.” He concludes by writing, “I am in the best of health—we have a fine crew and the ship is in A-1 condition so we shouldn’t have any difficulty to speak of. My love to each and every one of you. Love Jimmie”

His orders sent him not to South America or Brazil, but to North Africa.

A Connection to Home

The World War II soldier relied on mail to stay psychologically connected to home. Communication with family was a critical factor in the morale of the soldier. Mail call traditionally has been a highlight (and occasionally a low point) of a soldier’s time in combat. This is evident in a January letter from Jimmie. “I had 25 letters and cards waiting for me,” he concluded. “It’s the best time in the world right now.”

Two weeks into his journey, Jimmie wrote home, assuring the family that he was fine. He began this letter much like he ended the previous one with the disclaimer, “I can’t tell you just where I am at this writing, except that I’m in the air over foreign soil.”

Recognizing this recurring reference to censorship is important in considering a soldier’s ability to communicate with home. Silence was considered a strategic defense in the fight for freedom. Men and women in the armed forces, whose job it was to review and censor mail for classified or militarily sensitive information, would excise text from a letter with a sharp knife, leaving holes in the stationary. Not only military personnel but also workers in factories producing war goods were cautioned not to talk about what was being made.

One way of reinforcing this silence was a poster campaign. A group of 26 art organizations representing 43 states combined to create “Artists for Victory.” In 1942, posters were designed as reminders of all aspects of the war, but many spoke directly to the value of silence and censorship. They carried phrases such as “Loose Talk Sinks Ships,” “Someone Talked,” and “Zip Your Lip America. Loose Talk Is Dangerous.” This censorship, although understood and accepted by soldiers and factory workers alike, was difficult to master.

Jimmie, eager to assure his family of his safety and give them enough information to feel connected, had to overcome censorship hurdles. In his early letters he wrote on both sides of the stationery, rendering his letters indecipherable, as the reader wasn’t even sure, in looking at the letter, which side had been redacted. It also took him several letters before he became accustomed to words and phrases that were not acceptable to the censors.

On November 24, 1942, he wrote, “If the above isn’t censored it will give you a faint idea of where I am.” But it had been heavily censored, leaving literally large holes in the paper and no clues for the family as to where he was. He was cognizant of the censorship and wrote that writing was getting to be a tough assignment. “Never having been fond of it when I could set [sic] down and write just anything that came to my mind, but if I were to do that now you either wouldn’t get the letter or else it would look like a crossword puzzle by the time the censors were through with it.”

On March 30, he wrote home saying, “I’m sorry my letter of Feb. 3 was so badly censored. It must have been spot censored because our own censor usually tells us if anything is wrong. Save the letter and maybe I can fill in the spaces when I get home.”

A Cryptic Writing Style

He became more adept in his writing, and in a short time his letters were no longer like crossword puzzles. He began to communicate covertly, as in his letter written on March 11, 1943, when he simply told the family they might enjoy the December 21, 1942, issue of Life magazine. Two articles appear in that issue, “African Airfields Are a Headache to Pilots” and “The Battle for Tunisia: The victory runs into trouble.” These articles would have informed the family of his approximate whereabouts.

Jimmie continued in this way on March 30, writing, “My APO is 681 and that is all I can tell you. Orders from headquarters.” His next letter read, “Did you get the gist of what I told your father in my last letter? The AP dispatch which I enclosed probably gave you a better idea of what we’ve been doing than what I’ve been able to tell you in my letters.”

Government censors were concerned with locations and actions about troop activities. Self-imposed censorship, however, is also evident in the letters. This censorship protected Jimmie’s family from the realities of war.

Jimmie’s letters and the journal entries of the corresponding days reveal contrasting perspectives. His January 14, 1943, journal entry reads: “Getting ready to make some coffee this afternoon when I was interrupted by Ack-Ack breaking loose. It was just an observation plane, however. Maybe we will have a visit from Jerry tonight. An anti personnel bomb just blew up and put a block of holes in the Majors [sic] tent and one piece traveled about fifty feet and hit Pt. Hausel. No damage, flying suit stopped it.”

On January 15, he recorded the following in his journal: “Went to the front with a load of tires. Flight and drop successful. Landed and were taxiing to parking space when our right wheel hit a mine. It blew off the landing gear-—propeller—engine buckled the wing and filled the forward fuselage full of holes. The biggest of which were right through the radio compartment. Fortunately I received only a bruised elbow. It was a close call—too close for comfort. Plane can not be fixed.”

In a letter home dated January 16, Jimmie wrote, “Dear Mother and Dad, As usual I don’t know what to write about. Things are rather quiet in a way. Suffice it to say that, at the moment I am in good health and in no immediate danger.” His continues, “I was just wondering the other day if you ever received the dollar bill I send to you from Trinidad? You never mentioned it. Also, you never said that you received my Christmas card.” He finished with, “I suppose that at this time you are in the midst of snow and cold weather. I hope someone is making use of my overcoat. Au Revoir, Love, Jimmie”

The War and Entertainment

Over time, Jimmie’s journal entries divulge all kinds of information. “While I was on guard duty the mess tent and fifteen days rations burned to the ground,” he advised. On another occasion, he said, “While getting ready for take off the crew chief on 61 walked into a spinning propeller. Doesn’t look good.” He references countless attacks by the Germans on his base, for example: “Jerry was over again, last night. The show lasted almost an hour. They got four planes.” This last attack would deplete, even further, an already disabled air fleet.

These serious episodes are juxtaposed with more mundane concerns. In keeping with his love of entertainment, he wrote in his journal the title of each movie he saw, such as Bette Davis and Errol Flynn in The Sisters and Rudy Valle in Too Many Blondes. His journal also recorded all of his wins and losses in poker games. On April 5, 1943, he wrote, “Played poker this evening and won a little over $34. I’m recouping my loses [sic] a bit.” He even detailed having been grounded for being, in his words, falsely accused of stealing canned peaches from the mess tent.

In his corresponding letters home, Jimmie wrote of day passes granted and recent travel to Cairo. He sent pictures of himself with “the fellows” in front of the Gaza pyramids.

He shared his enthusiasm for good entertainment in a June letter referencing a band he said was “the best we have seen since we left the states.” He went on to say, “They [the band] were accompanied by Josephine Baker, a Blues singer who was the rage in Paris for quite some time.”

His letters also reflect his desire to return home, with such statements as this one about his nephew and niece: “Billy III and Alice should be pretty well grown by the time I get home. I’m looking forward to seeing them.” He painstakingly explained his financial plan to the family so that they could be the caretakers of his finances in his absence, which consisted of sending home $50 monthly in bonds, $20 each month for his mother, saying “this is hers to do with as she wishes,” and investing $200 in the Army bank at 4 percent interest.

“We Regret to Inform You”

In the midst of it all, the value Jimmie put on his relationships at home is edifying. He never once referenced information in his letters that he believed would upset his family, though many of his journal stories are sobering. One final example of his need to protect the family came in what was an obvious response to a letter he received from Mildred, his sister. “I think you read something between the lines Sis that wasn’t there. I’m not homesick. I’d like to be home, naturally, but so would everyone else. As it is we are probably living as well if not better then [sic] you are at home with all the rationing you have to contend with.”

His job, it seemed, was to literally protect himself from harm while figuratively doing the same for his family. This phenomenon is obvious even in this final journal entry and corresponding letter. The journal entry for July 8, 1943, reads, “Didn’t do much of anything this morning. Had a lecture on escape. Has a meeting this afternoon at headquarters, of all the [radio] operators in our mission in Sicily tomorrow night. It will be the first time we’ve dropped paratroopers on enemy soil.”

The letter of July 4, 1943, reads, “Dear Mother and Dad, If we could believe rumor. It would say it won’t be too long before we would be heading for home. However, we must take them for what they are and hope for the best. Things are quiet here at the present time yet the situation is quite tense. We are not doing much flying right now and as a result we are getting guard duty quite often. I got paid today and I put another forty dollars in the bank. I will need it when I get out. That will be all for now Mother. I am in the best of health and hope to see you soon. Love Jimmie.”

The next letter my grandmother received began, “We regret to inform you …”

Calling Home from War: The Modern Military Experience

The modern U.S. soldier, although aware of governmental classified information, may never know the same level of censorship as the World War II soldier. There is no need for soldiers to code letters in order to communicate their location to an anxious family. Posters reminding citizens of the importance of secrecy have been replaced by reporters embedded in troop action and onsite media coverage of the war as it occurs. However, the value the soldier puts on family communication remains strong. A recent government report addresses, among other things, advances in modern communication technology and its effects on the competing demands of family and mission. The once innovative V- Mail system has been replaced with cell phones and Internet instant messaging in the forward operating bases (FOB).

An FOB is a place where the discomforts of combat commonly experienced by the World War II soldier become a thing of the past. Jimmie wrote of scorching heat in the North African desert, tents that would regularly blow over in sandstorms, and Spam and white bread sandwiches three times a day. The FOB comes equipped with air-conditioning, hot showers, abundant food, and much more. It is a refuge from the mental stress of war and, because of modern technology, a means of staying connected with family and friends.

A U.S. soldier in Iraq using a cell phone can call home any time for only four cents a minute; laptops equipped with broadband give soldiers free Internet capability at their bunks. Unlike Jimmie’s experience of waiting weeks if not months for mail and packages, much of the contact with family and friends today is immediate. Self-imposed censorship is unnecessary, if not impossible. Soldiers remain an integral part of the family while simultaneously functioning as part of a military community. What soldiers sought in World War II letters from home was unmistakable. They wanted to remain connected to the daily lives of family and friends.

Technology may have caused a shift in the wartime paradigm, but the psychological stress of soldiers living in two worlds remains the same. The life of a combat soldier in World War II or the present Iraq war was and is a constant tug between duty to the military and duty to one’s family.

Maura B. Delaney is the youngest daughter of the late Florence and Thomas Delaney. She is the assistant dean for administration in the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences at Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She is currently working on a book based on the letters of her uncle, Corporal James G. Delaney.

This article is a very touching reminder that even the world’s biggest event was a collection of individual stories.

In a lighter vein, it also reminds me of something I read many years ago (in Readers Digest, maybe?).

Apparently there was a soldier who invented a code to tell his parents where he was — he’d use different middle initials to spell out the name of the place.

The letters arrived out of sequence, however, leaving the soldier’s parents wondering, “Where the heck is Sunti?”

Finally, a joke from Playboy, circa 1967.

A soldier wrote home: “Dear Mom & Dad, I can’t tell you where I am, but yesterday I shot a polar bear.”

Next letter: “Dear Mom & Dad, I can’t tell you where I am, but yesterday I danced with a hula girl.”

Third letter: “Dear Mom & Dad, I can’t tell you where I am, but the doctor says I should have danced with the polar bear and shot the hula girl.”