By Robert L. Durham

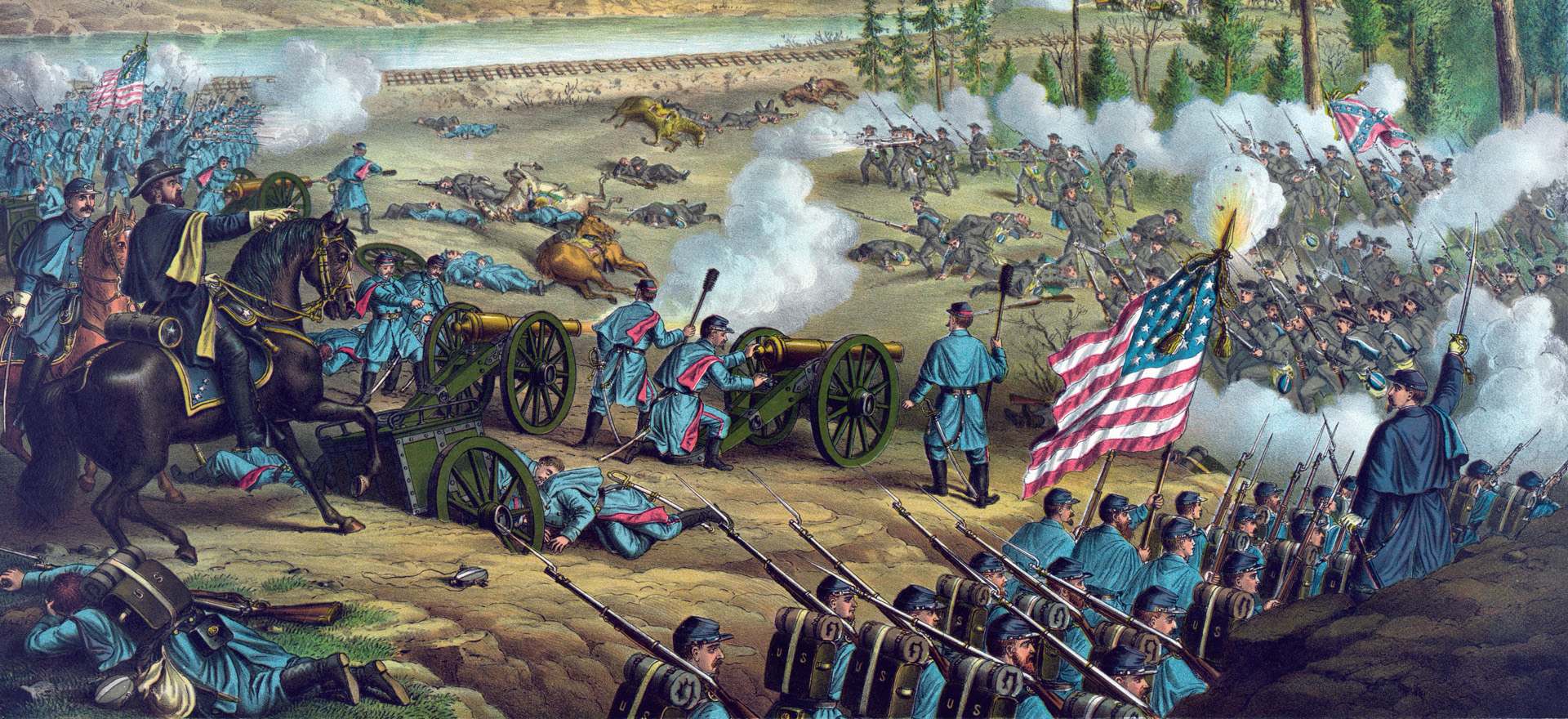

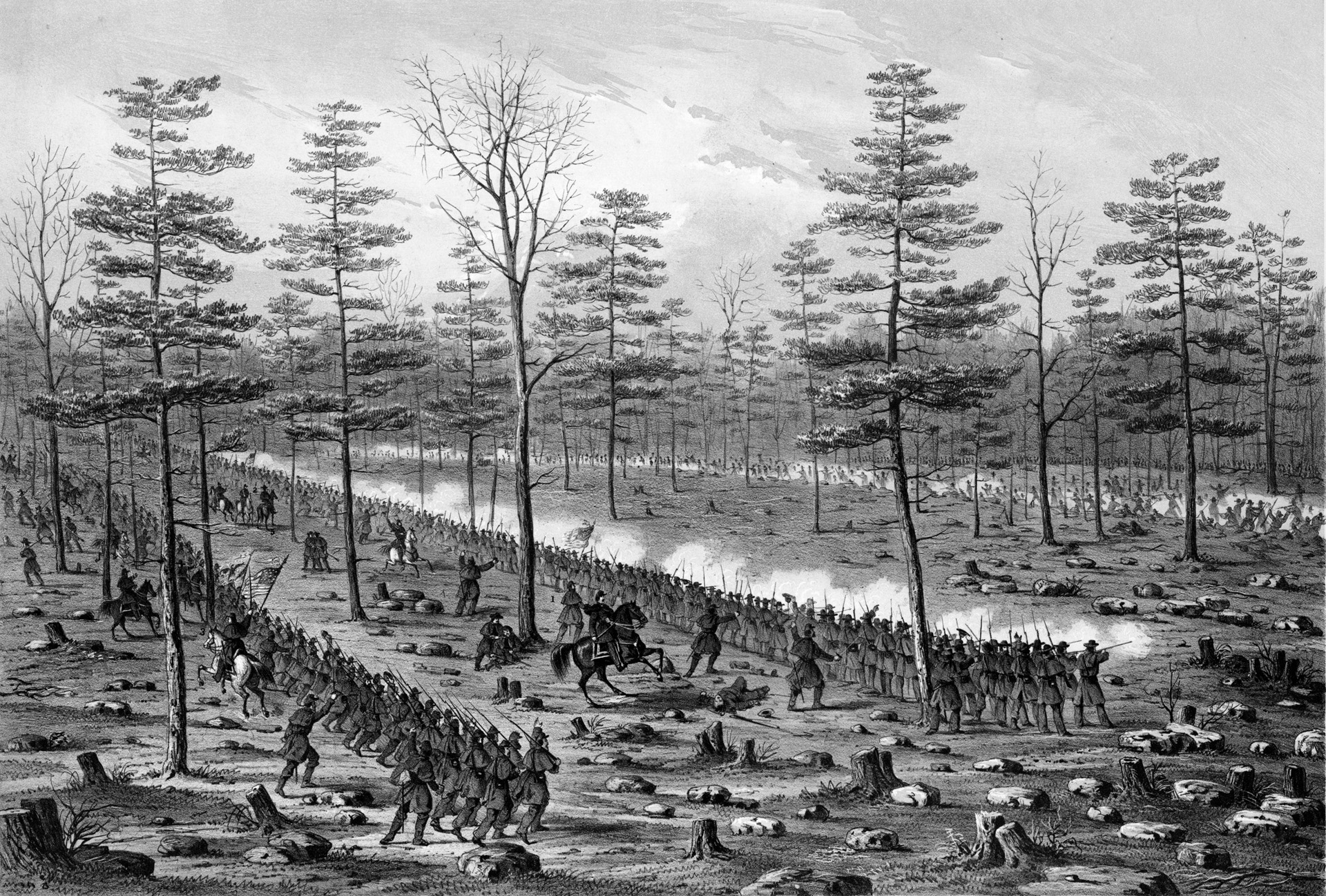

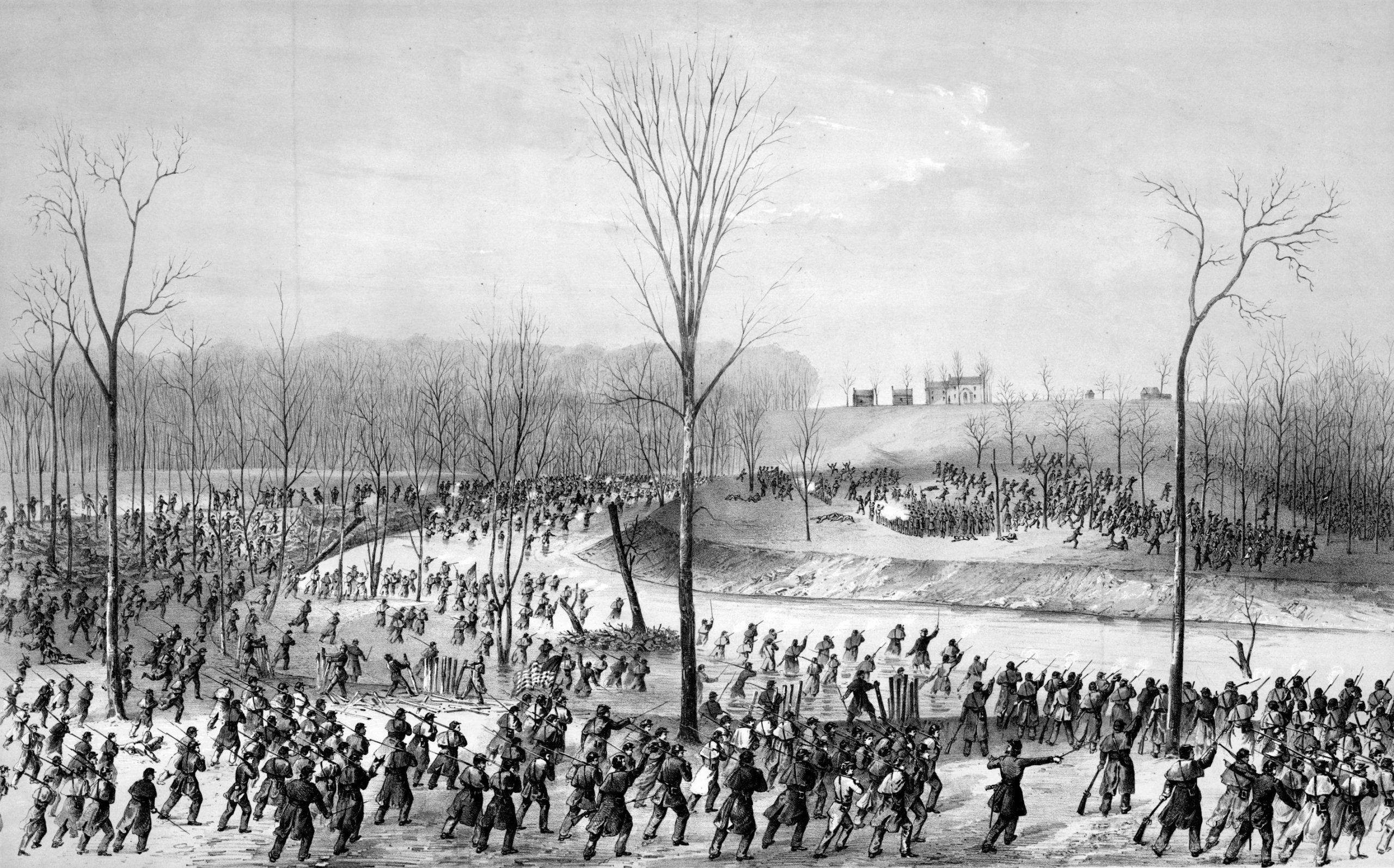

One of the most hard-fighting divisions in the Army of the Cumberland, the one led by Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan, had slowed the Confederate army’s sledgehammer attack on the morning of December 31, 1862, at Stones River; but even Sheridan had to fall back three times in the face of the relentless waves of Rebels who raced across the fallow fields and fought their way through a screen of scrub cedars in their quest to reach the Nashville Pike.

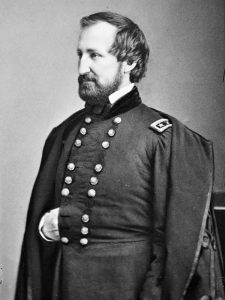

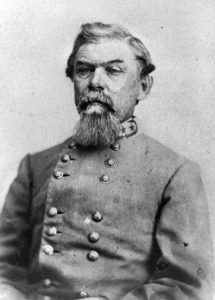

One of the best things going for the Army of the Cumberland was Maj. Gen. George Thomas. The Virginia-born Union general commanded the corps deployed in the center of the Union army. Thomas barked a series of terse orders that bought time for additional troops to arrive from the army’s left wing.

“Take your brigade over there and stop the Rebels,” he instructed Colonel O.L. Shepherd, who commanded veteran U.S. regulars who could be relied on in an emergency. They took up a position on high ground along the Nashville Pike to protect the army’s supply lines to Nashville. The commanders of the units engaged on the Federal right wing repaired their wounded commands and braced for more Confederate assaults.

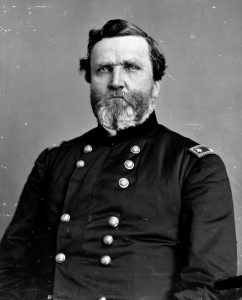

Meanwhile, army commander Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans rode along Union lines at midday shoring them up. He massed artillery near a clump of trees that would become known afterwards as Hell’s Half-Acre for the intensity of the fighting that unfolded at that location. The Confederates also were exhausted, but they continued their relentless attacks on the Union right into the afternoon.

The Murfreesboro Campaign was the culmination of Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s 1862 invasion of Kentucky during the so-called Heartland Campaign. The campaign reached a climax when Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio clashed with Bragg’s Army of Mississippi at the Battle of Perryville in central Kentucky on October 8, 1862. The battle was a tactical draw, but Bragg retreated south, handing the Union a strategic victory. Bragg did not stop his retrograde movement until he reached Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

Buell followed Bragg cautiously, stopping his pursuit at Nashville, Tennessee. President Abraham Lincoln grew weary of Buell’s slow movements and replaced him with Rosecrans, who renamed his new command the Army of the Cumberland. Lincoln had great hopes for Rosecrans, but he disappointed the president by not advancing that autumn against Bragg at Murfreesboro.

Bragg did not believe the Union army would make a major move before winter, so he ordered his men to build cabins for their winter quarters. Rosecrans planned to eventually lead his army to Murfreesboro, but he stayed in Nashville to reorganize and resupply his new command. Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, the general-in-chief of all the Union armies, informed Rosecrans that he would be replaced it he did not press south against Bragg’s line at Murfreesboro. But the stubborn army commander refused to move against Bragg until he deemed his forces ready. In particular, Rosecrans had concerns that his cavalry was outmatched by the Confederate cavalry. Under great pressure from Washington, he finally departed Nashville on December 26 bound for Murfreesboro.

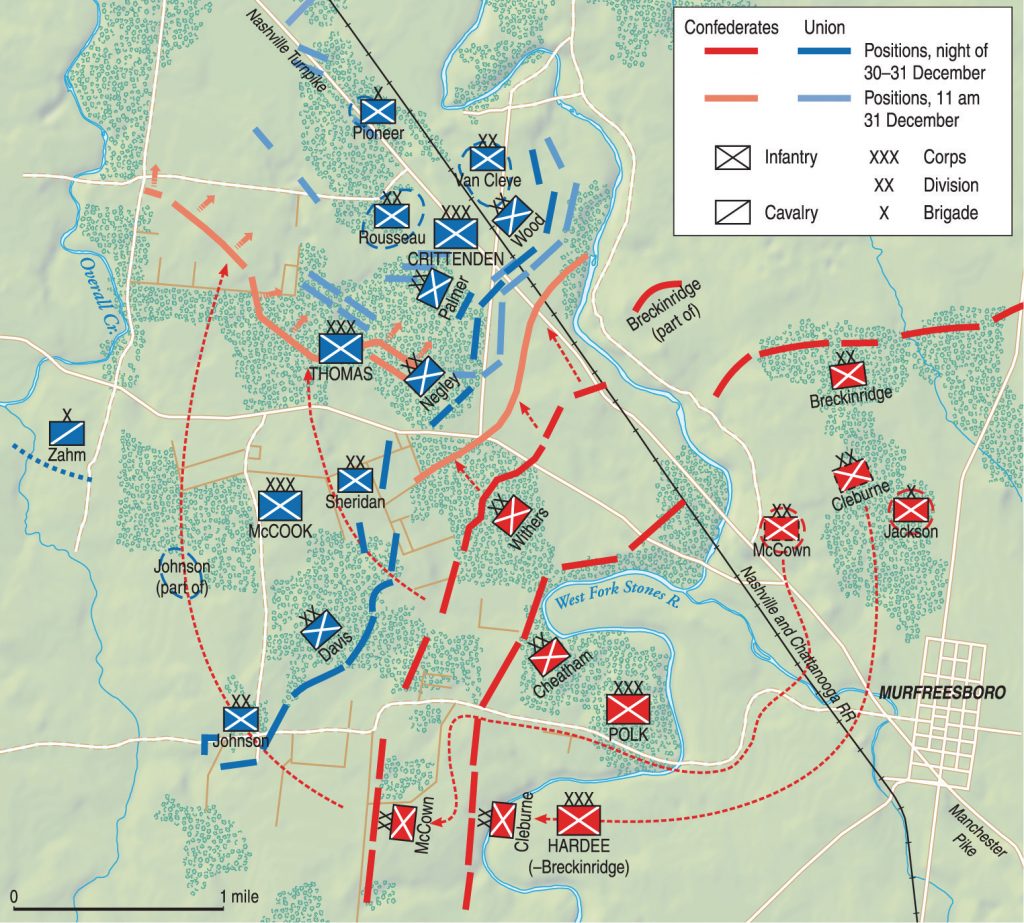

The 44,000-strong Army of the Cumberland moved in three columns, which Rosecrans called “wings.” Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden’s 14,500 troops of the left wing marched south parallel to the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. Maj. Gen. Alexander M. McCook’s 16,000-strong right wing advanced along the Nolensville Turnpike. Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas’ center wing, composed of 13,500 men, moved south along the Wilson and Franklin turnpikes, and then east along the Nolensville Pike behind Crittenden’s column.

The Yankees marched south beneath dark, brooding skies buffeted by wind gusts. Rain soon began to pelt the army. “Tramp, tramp in the mud and rain, onward among the old scenes,” wrote Corporal Ebenezer Hannaford of the 6th Ohio. “Rain, rain, rain—it would never cease raining.”

Confederate cavalry effectively screened Bragg’s dispositions from Rosecrans, while also furnishing the Confederate general with valuable information on the Union advance. Rosecrans reached the north bank of the West Fork of Stones River, a shallow left tributary of the Cumberland River, on December 29. Just two miles northwest of Murfreesboro, he deployed his forces to engage Bragg.

The Confederate commander had deployed his 35,000 troops in a line that ran northeast to southwest with troops on both sides of the river. He had not issued an order to entrench because he intended to attack the Federals. Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk’s corps was stationed on the left, on the west bank of Stones River, and Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s corps was deployed on the right, on the east bank of the river. When it looked like Rosecrans would assault his left, Bragg moved most of Hardee’s Corps across the river to his left flank, but he held Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s Division as a reserve on the east side of the river.

Crittenden commanded the left, Thomas the center, and McCook the right. From Stones River to just beyond the Wilkinson Pike were Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood’s division, Brig. Gen. John Palmer’s brigade, Brig. Gen. James Negley’s division, and Brig. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s division. From Sheridan’s position to the Franklin Road were the divisions of brigadiers Jefferson C. Davis and Richard W. Johnson. The reserve of each division rested in the rear of its respective division.

Rosecrans wished to deceive the Confederates into believing that he intended to launch a major attack against Bragg’s left flank, so he ordered no fires be built where his troops were encamped in line of battle. The Union army commander detailed some of his troops to construct large fires off to the right in an effort to fool the enemy into believing he was massing troops for his attack in that area. Rosecrans instructed Lt. Col. Bassett Langdon, who had a booming voice, to take up a position near the bonfires and pretend he was issuing orders to troops stationed in that sector.

Both sides settled down to a restless night. The two armies were 700 yards apart. “The night was quite cold, and the ground saturated with water,” wrote David Lathrop, the historian of the 59th Illinois. “Without blankets or fires, the men shivered through the night.”

Bragg’s plan of attack called for Maj. Gen. John P. McCown’s and Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne’s divisions of Hardee’s Corps to turn the Union right flank and gain the rear of Rosecrans’ army. Bragg’s ultimate objective was to cut off Rosecrans from his base in Nashville. Ironically, their plans were essentially the same: to turn the other’s right flank. Rosecrans issued orders on the night of December 30 for an attack the following morning against the Confederate right.

Rosecrans had scheduled his attack to start after breakfast, but Bragg got the jump on him by attacking at first light on December 31. Hardee’s two divisions stepped off at 6:00 am. Well-dressed Rebel lines advanced past the Widow Smith house with their cross-barred Confederate battle flags adding a splash of color to the bland winter landscape.

McCown’s division of Hardee’s corps advanced on the Confederate left. His brigades from left to right were led by brigadiers James E. Rains, Matthew D. Ector, and Evander McNair.

Rains’ brigade on the extreme left of the Army of Tennessee had the most ground to cover. His brigade comprised the 29th North Carolina, 11th Tennessee, and 3rd and 9th Georgia battalions. The 29th North Carolina spearheaded the assault.

A thick fog masked the Confederate advance from the prying eyes of Union pickets and enabled the Rebels to take the Yankees by surprise. “The color of their uniforms blending with the gray of the morning rendered their movements discernible only by the terrific fire of artillery and musketry,” wrote Johnson.

Rosecrans’ troops were sipping coffee and nibbling on hardtack when Confederate minie balls began zipping through the cold air of early morning. McCook’s soldiers bore the brunt of the first wave of the Southern attack. Brig. Gen. August Willich, of Johnson’s division, bent his brigade back in a right angle in an effort to protect the Union right flank. Brig. Gen. Edward Kirk’s brigade to his left, as well as Colonel Philip Sydney Post’s brigade of Davis’ division, also experienced the full fury of McCown’s assault.

McCown’s men rushed through a cornfield and advanced into a copse of cedars to engage Johnson’s startled bluecoats. Cleburne’s division went into action to the right of McCown’s troops. The native Irishman found his troops facing those of Davis. Cleburne’s troops had orders to fire several volleys and then charge the enemy. They succeeded in dislodging Davis’ troops, and the entire Union right wing began to give way.

“This early attack caught the enemy totally unprepared—not in line and cooking their breakfasts,” recalled Captain Irving A. Buck, assistant adjutant general of Cleburne’s brigade. The ground fought over consisted of limestone ridges and cedar thickets and was interspersed with farmhouses and cleared fields. The cedar thickets were often so thick that they made it impossible for the soldiers of both armies to see but a short distance “The continuous roar of musketry and artillery made it difficult to hear orders by voice, and the direction of movements were on both sides at times by the bugle,” wrote Buck.

On the right of Cleburne’s division, Brig. Gen. Lucius E. Polk, a nephew of Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk, led his troops through a patch of cedars and ran headlong into a Yankee line. A vicious struggle ensued with each side trying to gain an advantage.

“The fight was short and bloody, when the enemy gave way, both in the cedars and open ground,” recalled Cleburne. The 8th Arkansas of Brig. Gen. St. John Liddell’s brigade captured two stands of colors. The 2nd Arkansas met and defeated the 22nd Indiana and captured its lieutenant colonel. Liddell’s Brigade also captured two rifled cannon. The Confederates pressed the guns into service and used them for the remainder of the battle.

Similarly, Brig. Gen. Bushrod R. Johnson’s Tennesseans captured a four-gun Union battery. It was the first of two batteries the brigade would capture that day. The 16th Arkansas of Brig. Gen. Sterling A.M. Wood succeeded in capturing the colonel of the 101st Ohio, as well as killing the lieutenant colonel and the major of the Buckeye regiment.

Hardee committed Cleburne’s only reserve, which was Brig. Gen. Sterling Wood’s two Alabama and two Mississippi regiments, into a gap that opened up between Cleburne’s left and Maj. Gen. Jones M. Withers’ division of Leonidas Polk’s corps.

The butternuts of the 29th North Carolina began firing at the blue-coated Federals opposite them, as did the regiments deployed to their right. “The hiss of minies was incessant,” wrote Vance. The Tarheels captured an artillery section in which the guns were loaded but unfired.

The 77th Pennsylvania, which was deployed on the right of Post’s brigade, was one of the few Union regiments prepared for the attack. Its bluecoats heard movement behind the enemy lines during the night and became convinced than an assault was imminent the following morning. For this reason, Colonel Post had ordered his men to stand to arms during the night.

The soldiers of the 59th Illinois, deployed in the center of Post’s brigade, heard enemy musket fire off to their right. Captain Hendrick Paine dispatched aides to locate the threat. The reconnaissance party “found the forests full of flying Negroes, with some straggling soldiers, who reported whole regiment falling back rapidly,” wrote Lathrop. “The fire continued to approach on the right with alarming rapidity, extending to the center.” Post ordered his right regiments to change front to face the threat.

During their advance, the Confederates frequently encountered enemy batteries barring their way. Rains’ troops had advanced steadily for the first few hours of the attack, but in late morning his Georgians encountered the enemy holding its ground in a copse of cedars. These were the bluecoats of Kirk’s brigade. Kirk sent an urgent dispatch to Willich requesting help. Almost as soon as he did, he received a mortal wound to his thigh. Away from his command at Johnson’s division headquarters, Willich was in the act of hurrying to get back to his brigade when he accidentally rode into enemy lines and was captured. The two brigades were driven back, despite putting up strong resistance.

During the clash with Kirk’s brigade, Rains, astride his horse, was struck by a Federal minie ball in the heart. He was dead before he hit the ground. His magnificent horse bolted into the Union ranks. “The fall of this gallant officer and accomplished gentleman threw his brigade into confusion,” noted McCown in his report. Command of the brigade devolved to Vance. Rains’ death adversely affected the progress of Bragg’s attack, for without his leadership his brigade suffered.

Deployed in the timber behind and to the right of Kirk’s infantrymen were the guns of Captain Warren Edgerton’s Battery E, 1st Ohio Light Artillery. The Georgians disrupted Kirk’s brigade, at which time they began taking fire from Edgerton’s guns. The Ohioan cannoneers got off six rounds of solid shot before Rains’ men, charging at the double-quick, overran the guns. Edgerton, who had remained with his guns, fell prisoner to the Confederates.

By mid-morning Hardee had succeeded in pushing the Yankees back three miles. This bent McCook’s line back towards the Nashville Pike but did not break it. Hardee now faced a major challenge, for the Federal right wing remained intact. If Hardee hoped to seize the Nashville Pike before the day was over, his brigades and regiments would have to work in concert to achieve that objective.

Rosecrans had initially hesitated to call off Crittenden’s attack on the Confederate right, until he realized the seriousness of the situation. But once he determined that it was a major attack, he cancelled the assault and worked to shore up his deteriorating right wing.

Although Bragg’s attack against the Union right was in full swing shortly after sunrise, Rosecrans was not aware of the extent of the assault. As the Union soldiers of the right wing grabbed their muskets to blunt Hardee’s attack, Rosecrans had gone ahead in the early morning with his plans to assail the Confederate right. He ordered the lead brigade of Brig. Gen. Horatio P. Van Cleve’s division to ford Stones River and form a line of battle to attack Breckinridge’s division.

Rosecrans listened to the sound of battle on his right wing for nearly two hours before he eventually changed his plans. He was confident that the Union forces on the right wing would heed the orders he had given them the previous night to hold their ground. Even when he received a message from McCook requesting reinforcements, Rosecrans did not become alarmed. He sent an order to McCook reiterating that the right-wing commander must hold his ground.

Two of Van Cleve’s brigades crossed Stones River and the third brigade was making ready when Rosecrans received another, more urgent request for aid from units on his right wing. When crowds of skulkers and walking wounded began appearing in the woods, he knew for certain that a major Confederate attack was underway and that his right flank was in danger of collapse.

Rosecrans recalled the two brigades that had crossed the river at 8:00 am. He ordered Colonel James P. Fyffe’s brigade of Van Cleve’s division to march at the double-quick to Nashville Pike, where he believed the greatest danger lay. Rosecrans then dispatched Colonel Samuel Beatty’s brigade from Thomas’ corps to the right wing. He ordered Colonel Charles G. Harker’s brigade to follow Beatty’s Brigade and instructed Colonel Samuel Price to guard McFadden’s Ford closely to ensure it remained in Union hands.

Next, Rosecrans instructed Crittenden to pull back and consolidate his troops. Rosecrans told Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood, Crittenden’s First Division commander, to use Brig. Gen. Milo S. Hascall’s brigade of the First Division as a mobile reserve.

Last but not least, Rosecrans ordered additional rounds be distributed to the troops heavily engaged before riding to his right wing to oversee its defense in person. Just then, Lt. Col. Julius P. Garesche, Rosecrans’ aide, was beheaded by a cannon ball. The gore splattered Rosecrans’ uniform but did not shake the army commander.

Once Rosecrans realized that the Confederates were determined to fight their way to Nashville Pike, he took critical steps to protect his lines of supply and communications back to Nashville. One of these steps was to detach troops from Crittenden’s left wing to buttress the army’s center and right.

Whether the Union army survived Bragg’s attack would depend largely on Maj. Gen. Thomas’ corps in the center. The bluecoats of Thomas’ corps would bear the brunt of the fighting in the next phase of the battle.

After its initial advance, the 29th North Carolina reformed itself into a line of battle in order to ascertain how much ammunition its soldiers possessed. It was subsequently determined that they had just 10 rounds each. Rains’ troops faced three lines of resolute Yankee infantry with artillery interspersed between the regiments. “The fire was terrific, the treetops falling all around,” wrote Vance.

The murderous fire killed Vance’s horse and60 men of the 29th North Carolina in a few minutes. A courier from the 11th Tennessee informed Vance that the regiment had expended all of its ammunition and had no choice at that point but to fall back.

Ector’s Texas brigade, which advanced to the right of Rains’ brigade, consisted of four regiments of dismounted Texas cavalry. Like Rains’ Georgians, Ector’s Texans also engaged the Federals at the edge of the cedar brake. The Texans overran the Yankee skirmish line in front of them before the skirmishers could get into action.

“We drove them back on their main line so rapidly that we got to within easy gunshot of their main line before they knew it,” wrote Lieutenant J.T. Tunnell of the 14th Texas. “Many of the Yanks were killed or retreated in their nightclothes. We pursued them with the Rebel yell.”

When they came under Federal artillery fire, Ector’s men went to ground. “Our men sheltered themselves as best they could behind trees [and] ledges of rocks,” wrote Tunnell. At that point, the front line of the Yankee forces opposite Ector’s troops started to advance. “[They were] walking a few steps, then firing, and falling down to load.” Orders were passed down the Confederate line to retreat. Ector’s men reformed across an open field opposite the Yankees in the cedar brake.

Davis, who commanded the First Division in McCook’s corps, found himself directing what had become the right-flank division of the Union line. He ordered Post to move his brigade to a better position. Post’s brigade still had plenty of fight. The colonel shifted his troops from a thicket of woods to a position along a dirt lane that afforded each of his regiments a clear field of fire to the south. The untested left regiments, the 74th and 75th Illinois, were at the edge of a wood behind a split-rail fence on the east side of the lane, while the right regiments, the 55th Illinois and 22nd Indiana, deployed in fallow fields. The 5th Battery, Wisconsin Light Artillery, led by Captain Oscar Pinney, deployed its 10-pounder Parrott Rifles in a cornfield in the center of the brigade.

Post’s brigade faced Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s brigade of Cleburne’s division. Captain Putnam Darden’s Jefferson (Mississippi) Artillery dropped trail behind the left regiments. While endeavoring to perform the right-wheel movement that Bragg had ordered, the three brigades of Cleburne’s division had advanced at different speeds. This resulted in the brigades losing contact with each other.

Lt. Col. Peter B. Housum led a portion of his 77th Pennsylvania regiment forward to try to capture the Rebel guns posted 500 yards away. The Yankees ran headlong into Confederate canister and musket fire that threw them back with considerable loss. Housum was slain in the bloody assault.

Colonel John S. Fulton’s 44th Tennessee faced Post’s left regiments behind the split-rail fence. “[Fulton] led his regiment with such vigor and gallantry that no Federal force could withstand its terrible, death-dealing blows,” wrote Sergeant G.W.D. Porter. The blistering Yankee fire pinned down the Tennesseans. Seeking to dislodge the Yankees, Fulton ordered his men to charge. Under a terrific fire from the Federals, the Tennesseans came to within 50 yards of the position of the two green regiments.

When his men wavered, Fulton rushed forward. “Forward, my men, forward!” he shouted, brandishing his sword. The Tennesseans erupted in the Rebel Yell and rushed over the remaining ground. They fell upon the bluecoats behind the split-rail fence, driving them back in confusion.

Yankee regiments were toppling like dominos as the fighting wore on throughout the morning. The combined weight of Brig. Gen. Lucius Polk’s Arkansas-Tennessee brigade and McNair’s Arkansas brigade proved too much for Colonel Philemon P. Baldwin’s brigade of Johnson’s division. McNair’s troops covered 300 yards of ground at the double-quick. In their rush close with the enemy, the Arkansans smashed through several split-rail fences. When the Confederates came to within 75 yards of Baldwin’s line of battle, the troops on his right side broke and fled. At least the troops on the left side initially held their ground, but then they also fled. Cleburne’s hard-fighting division had succeeded in routing a total of five Union brigades.

Rosecrans ordered Thomas to send his First Division, which was commanded by Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau, to support Sheridan’s division. Sheridan’s division had gone unscathed in the initial Confederate assault because Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham had been slow to get his four brigades into action. It would later turn out that the reason for Cheatham’s dilatory performance was that he was drunk.

Hardee sent a courier to Bragg, informing him of the delay. Bragg then dispatched a messenger to Cheatham telling him to advance at once. But when Cheatham’s brigades finally did go forward, they did so in a piecemeal manner. This diluted his attack and afforded Sheridan an opportunity to shift forces as needed to meet each emergency that arose.

The first attack Sheridan experienced at 8:00 am did not come from one of Cheatham’s brigades, but rather from Colonel John Q. Loomis’ brigade of Maj. Gen. Jones M. Withers’ division. Loomis’ right regiments struck brigadier Joshua Sill’s brigade, while his left regiments took on elements of Colonel William E. Woodruff’s Brigade of Davis’ division.

Sill’s brigade followed in a determined charge; his bluecoats succeeded in driving back Loomis’ brigade to its starting point. “In this charge, the gallant Sill was killed, a rifle ball passing through his upper lip and penetrating the brain,” wrote Sheridan. Command of Sill’s brigade devolved to Colonel Nicholas Greusel of the 36th Illinois.

The third Rebel assault, against Sheridan’s line, outflanked his forces. Sheridan ordered Colonel George W. Roberts to attack with his brigade. Sheridan’s rationale was that Roberts’ counterattack would cover the withdrawal of the rest of the division’s units. By that point in the battle, all of the units in the right wing of the Union Army had been driven from their initial positions. By 10:00 am the Confederates had seized more than two dozen Union artillery pieces and captured 3,000 prisoners.

After disrupting the Union right wing, Bragg’s army began to assail the Federal center. If they could succeed in punching through the center of the Union army or drive back the Union right even father, the Confederates might be able to seize Nashville Pike. That would cut the Yankees off from their only means of withdrawal. But the tide was slowly turning in favor of Rosecrans’ army.

In compliance with Rosecrans’ orders, Thomas had dispatched two brigades of Rousseau’s Division to support Sheridan’s right flank, but he eventually sent the remaining two brigades to join it. Thomas also assumed command of the Union right wing.

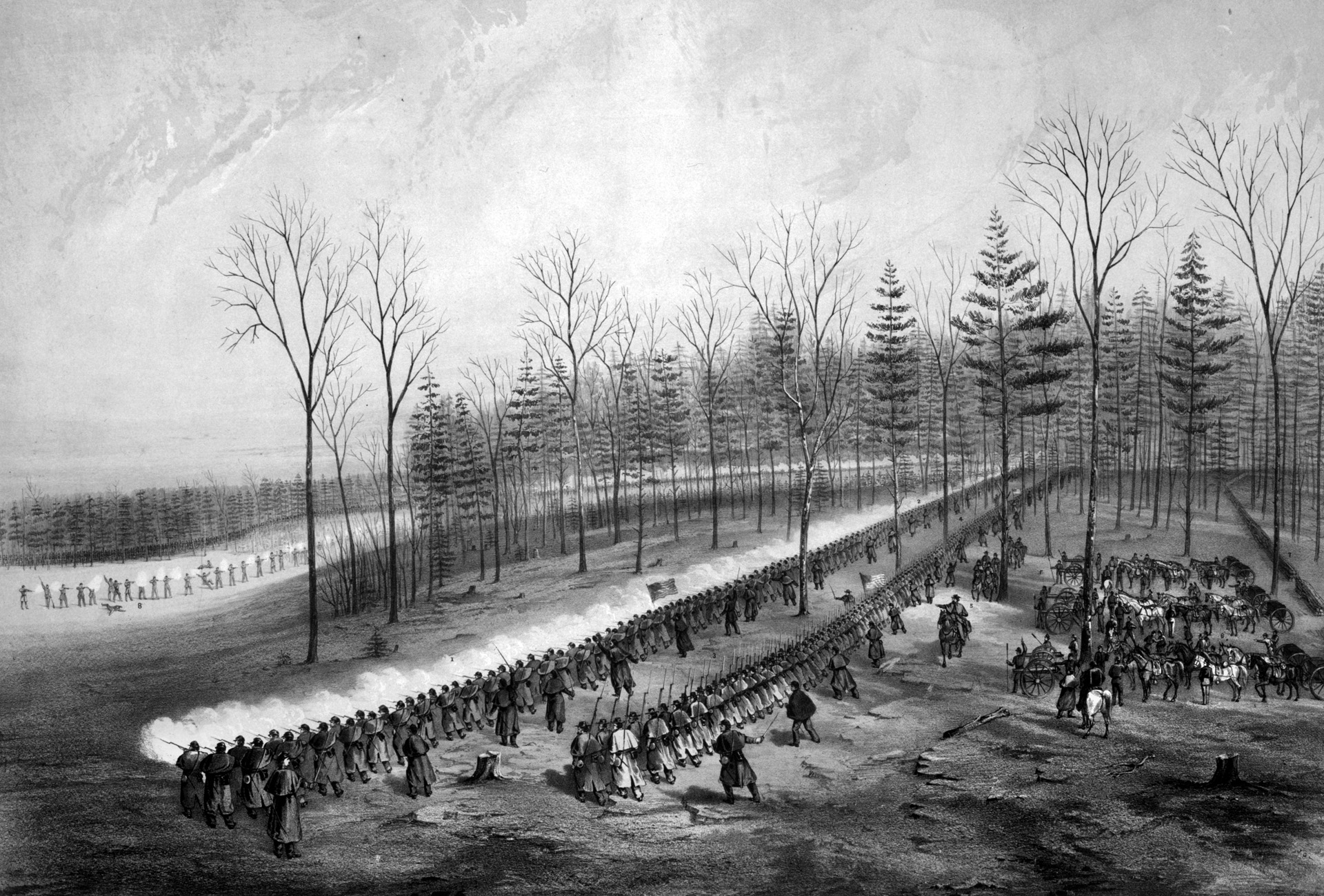

Thomas and Sheridan’s division of McCook’s corps formed their respective units into a V made up of troops of all three sections of the Army of the Cumberland. On the right flank was Rousseau’s division, in the center Sheridan’s division, and on the left flank McCook’s forces. Two of Negley’s brigades supported Sheridan at the bottom of the V, and three brigades of Palmer’s division supported the left flank of the V.

The responsibility for the Union line lay firmly in the capable hands of Thomas, who directed its defense with meticulous diligence. Known for his steadiness under attack, Thomas moved up and down the line making his presence known to all frontline troops under his immediate command. Maintaining this position was imperative to give Rosecrans enough time to organize a new battle line in front of the Nashville Pike. Rosecrans held the life of his army in his hands. If the Confederates seized Nashville Pike, they would essentially have the Union army surrounded.

Hardee moved to take the position in flank. He shifted Cheatham’s division to the right and sent it against Sheridan and Negley. The Rebel infantry surged forward anew. The high-pitched Rebel yell could be heard over the deep rumble of cannon and crashing thunder of thousands of rifled muskets. “The Rebels were falling like leaves of autumn in a hurricane,” recalled Private Sam R. Watkins of the 1st Tennessee. The Confederates fell back but soon reformed and came on again. A fragment of shell struck Watkins in the arm, and then a minie ball hit the same arm, paralyzing it. “Come on boys, and follow me,” shouted Cheatham. But Watkins did not follow owing to the severity of his wound.

Private Samuel Seay, who belonged to the same regiment as Watkins, waited for the command to charge from his regimental commander. Once it was given, the regiment surged forward. “Every man, with gun loaded and cocked, cartridge-box open, and at the front, instantly sprang forward,” wrote Seay.

Cleburne’s division made a rapid, albeit somewhat disorderly, pursuit of the Federals, until a fresh line of infantry and artillery came into view. Liddell’s and Polk’s brigades forced back the Yankees. “The enemy were driven back across the Wilkinson Pike, and took refuge in the woods and heavy cedar brake on the north side,” wrote Cleburne in his battle report.

The attacks of the Confederates twisted the Yankee lines into strange shapes. At one point, Miller’s brigade of Negley’s division was bent back upon itself. When Sheridan’s men ran out of ammunition, he ordered them to retire. Nearly all of the regiments of the Union right wing were running low on rounds as the morning wore on. Union soldiers desperate for cartridges searched through cartridge boxes of the dead and wounded. The Union troops did not receive timely ammunition resupply because the Confederate cavalry had succeeded in interdicting some of the ammunition wagons on Nashville Pike.

Because of the successful Confederate attacks, the fates of Rousseau’s left and Negley’s right were both up in the air. Miller’s brigade found itself being attacked in front and on both sides. The enemy moved against it “in heavy columns, firing deadly volleys of musketry, and also concentrating his artillery on this one point,” wrote J.T. Gibson of the 78th Pennsylvania, adding, “The roar of the artillery with the rattle of musketry was deafening, and the scene indescribably appalling.”

The 78th Pennsylvania received an order to retire, even though its troops were fighting bravely and holding their ground. The Pennsylvanians had fallen back 100 yards when they were ordered to retake their original position. They counterattacked and regained the ground lost to the Rebels, but they eventually received orders to retreat through the cedar break.

It was almost impossible to preserve regimental lines in the thick woods, and the Rebel artillery caused many casualties. “One shell exploded exactly in the line of the regiment on our left, killing, at, least, three men,” wrote Gibson. Nearly all the Yankee artillery horses had been killed. They passed an artilleryman trying to save his gun with only one horse. A wheel of the gun carriage was caught between two rocks, and he was attempting to pry it out, using a rail for leverage.

Lt. Col. Oliver L. Shepherd’s brigade of U.S. Regulars on the Union right flank performed exceptionally well. When ordered to advance from their reserve position, some confusion followed. Since they were to act as a reserve, they did not expect the terrible battle they were to enter. “The woods were darkened with soldiers flying from the line of battle, some wounded—others without hats or guns,” wrote Private Reuben Jones.

The regulars fired by platoons, beginning first on one flank and then on the other flank. The rolling fire forced Rains’ troops to fall back. Shepherd’s brigade lost one-third of its troops in a short period of time. Thomas ordered his units to pull back.

The brigades of Miller and Colonel Timothy R. Stanley sustained one of the most furious assaults of the day. As for Negley’s division, which was nearly surrounded, it had to cut its way out of encirclement in order to reach the safety of the main Union line. In so doing, it abandoned six cannon.

Negley’s retreat left Brig. Gen. Cruft’s Brigade of Palmer’s division with its right flank uncovered, and it also had no choice but to retreat. By that time, Sheridan’s original position had completely collapsed.

Colonel Willman B. Hazen, who led the Second Brigade of Palmer’s Division, had established a strong defensive position in the Round Forest where he intended to make a stand that would cover the Nashville Pike. Hazen’s command provided a rallying point for the retreating bluecoats. The remnants of various regiments fell in on both sides of Hazen’s position.

Hazen’s men repulsed repeated attacks by two fresh brigades sent across the river from Breckinridge’s division. The 41st Ohio moved across the turnpike, taking up a position on a slight ridge of open woodland. “The enemy came on in fine style to the attack of this position,” wrote Robert L. Kimberly of the 41st Ohio.

“The Rebel bullets were hissing all about us,” recalled Corporal Hannaford. “We were in action.” The corporal only fired three shots, the second from his knee, shooting low and deliberately.

“[Suddenly], a whistling volley of bullets came over…and for me the battle was over.” A minie ball had struck Hannaford in the throat, but all he felt from the actual wound was a croup-like sound when he tried to talk. He believed minie ball had struck him in the shoulder. “With a dull, aching feeling in my right shoulder, my arm fell powerless at my side, and the Enfield dropped from my grasp.”

Hazen held his ground by using the railroad embankment to protect his infantry and by relying on substantial artillery support. The Confederate brigades of Adams and Jackson fell back. The Union guns had shattered them. Two of Breckinridge’s brigades, those led by Brig. Gen. William Preston and Colonel Joseph B. Palmer, arrived on the west side of the river. Breckinridge led them into action. They were not only driven back, but also lost a number of men when the Yankees captured them in a countercharge.

Having achieved all that was possible against the determined Union resistance, the Confederates withdrew at nightfall. Rosecrans held a council of war that night. He and his corps commanders seriously considered retreating to Nashville, but in the end decided to stand and fight. As for the Confederates, Bragg believed he had won the battle. He issued orders for his men to entrench.

Bragg wired Richmond informing the Confederate government that he had won a major victory over the Union army. “God has granted us a happy New Year,” he wrote. He expected that the Union army would retreat the following day.

Rosecrans revived his original plan of striking the Rebel right. He ordered Van Cleves to lead his division across the river at McFadden’s Ford on January 1, 1863. Van Cleves took possession of a ridge overlooking the Confederate right that could be used by Union artillery to enfilade the Confederate right. Other than this, neither side made any moves on New Year’s Day.

While the Confederate infantry remained in its previous positions, Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry continued to harass Union wagon trains traveling on the Nashville Pike. Because of the continuing threat from Wheeler’s troopers, Rosecrans had to detach troops to escort the convoys of wounded journeying to Nashville.

On the morning of January 2, 1863, Bragg ordered Breckinridge to lead his division in an assault to retake the ridge overlooking the McFadden Ford. The former vice president of the United States protested because he felt the charge would be suicidal.

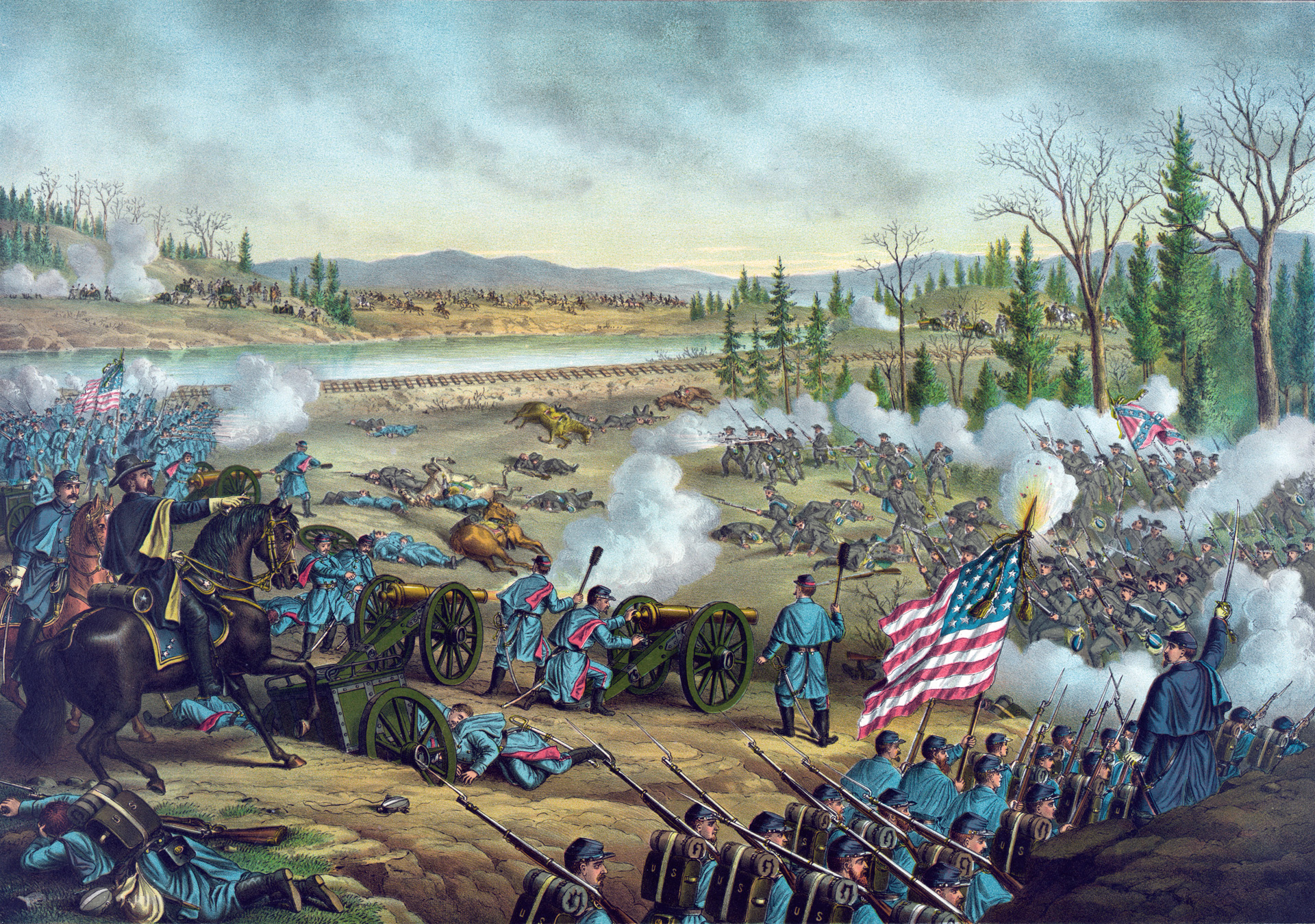

Rosecrans had previously instructed Captain John Mendenhall, the chief of artillery for the Union left wing, to mass Union artillery to thwart any Confederate attempt to cross the ford. Mendenhall deployed 45 of the guns hub-to-hub on the bluffs on the west bank. He also positioned another 12 guns to the southwest, where they could enfilade the Confederate line of attack.

In compliance with Bragg’s orders, Breckenridge’s 4,500 troops attacked in a driving rain at 4:00 pm. His soldiers succeeded in dislodging Brig. Gen Horatio Van Cleves’ troops from the high ground on the east bank overlooking the ford. As the Confederates pursued them down the reverse slope, they came under fire from the enemy’s massed artillery. Breckinridge’s command suffered 1,800 casualties in less than one hour.

In the aftermath of the debacle, Bragg decided to withdraw. He was acutely aware that the Union Army of the Cumberland had significantly more soldiers than the Army of Tennessee. Under cover of night on January 3, Bragg’s army slipped south 30 miles to Tullahoma, Tennessee. Rosecrans took possession of Murfreesboro on January 5.

Total casualties for the Federals at Stones River were 13,200 compared to 10,200 for the Confederates. Although it had been a close-fought battle, Rosecrans could claim a strategic victory, for he had forced Bragg to give up a substantial amount of ground to the Federals by withdrawing to the Tullahoma line.

By that point, the heady days of the Confederate’s Heartland Offensive were long gone. What followed was a grinding war of attrition as the Union army advanced relentlessly on the railroad hub of Chattanooga, Tennessee.